Brutal attacks on doctors and nurses is a sign of a broken healthcare system

Vincent Kolo, chinaworker.info

Several hundred Zhejiang hospital workers in white coats walked out on strike on 28 October. The staff at Wenling’s No. 1 People’s Hospital were mourning their colleague, Wang Yunjie, who three days earlier was stabbed to death by one of the hospital’s former patients. The numbers participating at the strike rally may have reached 1,000, according to some reports. The horrific knife attack that left Wang dead and two other doctors wounded was only the latest incident in a rising tide of violence against doctors and medical workers. China’s hospitals have become “war zones” in the words of the Global Times, a government mouthpiece.

The strikers, many wearing surgical masks to hide their faces, held banners that called on the government and hospital management to “guarantee medical staffers’ safety”. Staff at nearby hospitals staged solidarity protests and some medical workers from Jiangsu province took part in the Wenling rally. Online, the Wenling strike has spawned numerous ‘copycat’ actions with photos of uniformed staff appealing for an end to violence and a restoration of respect for the medical profession.

The Wenling strike and rally, organised through Weibo and text messages, seems to have had an electrifying effect on the consciousness of medical workers across China. “Doctors nationwide have never shown as much solidarity as they have since the incident in Wenling” a doctor in Guangzhou told the Global Times. The local authority and public security officials however reacted in customary fashion by sending in hundreds of riot police.

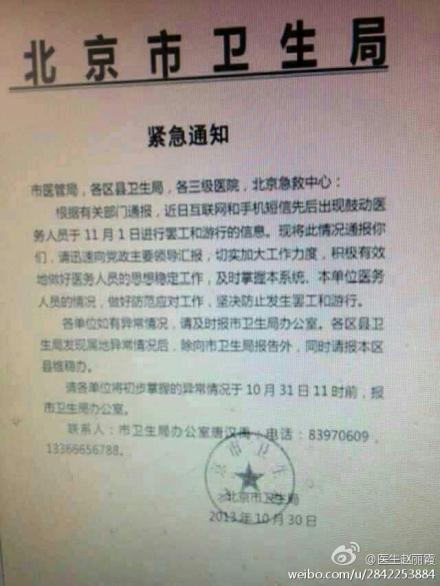

The Chinese regime at national level has clearly taken note of these stirrings of discontent. This is a sensitive time with the Third Plenum of the ruling party’s 18th Central Committee set to meet on 9 November, a high stakes meeting for the leadership of Xi Jinping and Li Keqiang. Showing how worried the authorities are, the Beijing public health bureau issued a notice instructing hospital management not to allow any protests or strike action by hospital employees. The notice said government was aware that “information and mobilisation” was being spread following the protests in Wenling, and said that any “abnormal” situation should be reported not only to hospital authorities but also to legal authorities (see picture below).

The slaying of Wang Yunjie is part of a worsening trend. Last week Xinhua news agency reported there had been at least six serious attacks in a ten-day period including an incident in Liaoning province where a man stabbed a doctor six times before jumping from the roof. On the Sunday before the Wenling strike, a nurse was taken hostage by a knife-wielding man at a hospital in Nanchang in Jiangxi province. A few days earlier a doctor in Guangzhou suffered a ruptured spleen and eye injuries after being assaulted by a patient’s relatives. Local government spokesmen in Wenling are hailing Dr Wang as a “martyr” but are not proposing any measures to improve the situation. The attacker, Lian Enqing, who suffers from mental illness, could face the death penalty. But for the authorities this would just be a means to cool the anger of the hospital staff without addressing the causes of the problem.

Assaults on doctors averaged 27.3 per hospital in 2012, a rise from 20.6 in 2008, according to a survey from the Chinese Hospital Association published in August this year. Hospitals are being turned into high security compounds with more security guards on duty and increased spending on surveillance cameras. The government issued new guidelines just before the Wenling attack saying there should be one security guard for every 20 hospital beds. But there is a growing realisation among health workers and the wider community that beefed up security is not a real solution. The liberal Southern Metropolis Daily in Guangdong province called the new security measures “simple and crude” and warned they could have the opposite effect by increasing tensions. But this newspaper’s alternative was just to propose the setting up of mediation systems to defuse conflicts between patients and hospitals. This is no more than a technical change that avoids going to the root of the conflict, which is the current commercialised model of healthcare. As Liu Jitong, a public health expert at Peking University explained, “Once the medical system decides that its aim is to ‘make money’, patients will not trust doctors anymore.”

“The system is rotten to the core”

As one doctor told the BBC’s Martin Patience, “I’m a Communist Party member. I probably shouldn’t say this but the system is rotten to the core. It’s hard to cure a deeply ingrained disease.”

The strained relationship between the medical profession and the public has arisen due to extreme neo-liberal healthcare reforms that have removed most government funding from the system and forced hospitals to squeeze money out of patients through high drug prices and costly, often unnecessary, treatments. Today’s system, with sky-high medical costs, often substandard care, and rampant corruption, is a result of the CCP regime’s shift from a bureaucratic but state-funded and controlled ‘planned economy’, to a brutal state-guided form of capitalism.

Even that global standard-bearer of neo-liberalism, The Economist magazine, recognises this basic truth: “When China’s market reforms began in 1978 medical user fees soared. The share of total health spending borne by patients rose from 20 percent in 1978 to nearly 60 percent in 2001. State-owned enterprises, which had once shouldered much of the burden, crumbled, and in 2000 the World Health Organisation ranked China fourth from last among 191 countries in terms of the fairness of financial contributions to its health system.” [The Economist, 21 June 2012]

Today, according to the Economist’s report, 40 percent of China’s hospital revenues come from the sales of medicines, and less than 10 percent comes from direct government spending. Corruption among doctors is a widespread public grievance, but they are merely the “end of the chain” as one insider put it. Most of the big kickbacks take place at the top between the pharmaceutical companies, hospital management and higher officials. As part of premier Li Keqiang’s new liberal economic reforms, the government plans to further open the healthcare sector to profiteers, allowing private companies to bid for government contracts in hospitals and elderly care. This will open new avenues for corruption.

The central government, fearing social unrest, launched a rudimentary health insurance scheme in 2006 to cover most, but not yet all, of the 650 million rural poor. But this healthcare scheme, part of Beijing’s plan to boost ‘consumerism’, is still far from adequate as revealed by a study in the British medical journal Lancet from 2012, which found that patients covered by the government’s health insurance scheme still bore 60-70 percent of outpatient costs from their own pocket, and more than half of the cost of inpatient treatment. The Lancet found that the percentage of households suffering ‘catastrophic’ health expenses barely changed between 2003 and 2011 despite the government scheme.

While medical costs are a cause of misery and poverty for millions, morale has plummeted within the medical profession. In a 2011 survey of 6,000 doctors by the Chinese Medical Doctor Association, 95 percent said they were underpaid and 78 percent said they wouldn’t want their children to study medicine.

Kick out the profiteers!

The strike in Wenling is a welcome sign that hospital workers are finding their collective voice, a necessary first step to changing today’s unbearable situation. To build upon this initiative health sector workers must set up their own independent and democratic trade union organisations.

They must demand a huge increase in public funding for hospitals, including increased salaries for doctors and other medical staff. Patients should build their own associations to press for their rights, working in concert with organisations of health sector workers. The profiteers must be driven out of the healthcare system, which should be fully publicly owned and funded. If this was possible in the 1960s and 70s, then it must be possible today when China is so much wealthier. The pharmaceutical industry’s economic blackmail needs to be smashed, by bringing these extremely profitable companies into public ownership under the democratic control of workers and patients/consumers, along with the hospitals themselves. Drug prices should be controlled by elected committees of health sector workers and consumer representatives to insure prices reflect genuine research and development expenditure, not super profits, wasteful branding, and bribes to officials, as is the reality today.