Jiangsu’s toxic school scandal highlights ecological catastrophe

Dahu, chinaworker.info

In March 2014 China’s premier Li Keqiang’s declared “war against pollution”. As smog levels in major eastern cities including Beijing went off the charts, the one-party dictatorship of the CCP (Chinese Communist Party) knew this issue could, much like the economic downturn and endemic corruption, be the trigger for mass unrest and the possible downfall of the regime.

Water torture

But little fundamentally has changed in terms of pollution since the government “went to war”. This week a study was published showing that 73 percent of the water sources accessed by the country’s 30 biggest cities suffer from serious pollution. This affects the water supplies for 80 million people. Previous studies have shown the extent of water pollution in rural China, which is actually worse. But these findings are a wake up call for city dwellers. The report was compiled by the Nature Conservancy, which tested water quality in 135 watersheds, in cities including Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, but also Hong Kong.

Go West

Also this week, Greenpeace produced a study showing that China’s air pollution has shifted westward. The findings show that toxic smog has eased to some extent in eastern cities such as Beijing and Shanghai, but worsened in interior regions. As part of Premier Li’s ‘war’, wealthier eastern cities have imposed caps on coal use and closed down coal-fired power plants in their immediate proximity.

But this has come at the expense of other regions, with an increase in new coal-plant construction in poorer western areas. The Greenpeace report argues this is “specifically because their air pollution and emissions regulations are more lax”.

Beijing and Shanghai both experienced a fall in levels of small dangerous airborne pollutants (PM2.5), in Shanghai’s case by 12 percent compared with a year earlier. Despite this, average PM2.5 levels in both cities are still at least six times higher than World Health Organisation guidelines.

Smog levels in several eastern cities triggered China’s first ‘red alerts’ in December, leading to the closure of schools and factories and restrictions on motor vehicle usage. Children and the elderly are ordered to stay indoors during such alerts.

Toxic schools

There has been a public outcry – even panic – since state media reported the case of two schools in Jiangsu province where pupils have fallen ill due to chemical pollution. In the first case, in the town of Changzhou, 500 school students have fallen ill, including cases of cancer. The school with more than 2,000 students was built close to where chemical factories that violated environmental laws once stood.

The Education Ministry sent a team to investigate the Changzhou Foreign Languages School, while Jiangsu officials are under pressure to re-examine an earlier ruling after they initially said there were no soil quality problems at the school site. A CCTV report implied that school and local officials had not conducted adequate tests for chemicals and heavy metals involved in the manufacture of pesticides.

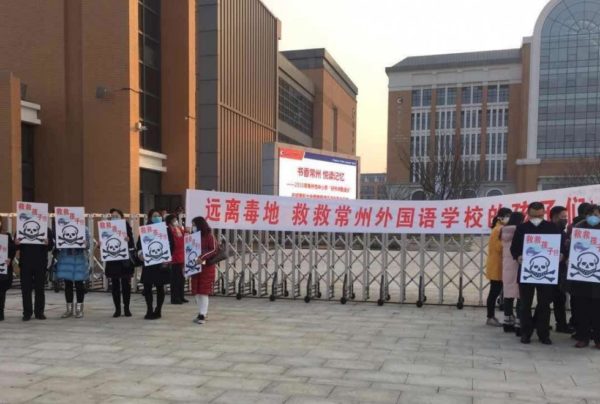

Soil at the site was discovered to have levels of chlorobenzene nearly 95,000 times the national limit. This is a solvent exposure to which can damage the central nervous system. CCTV’s report said the decision to build a school on the site was “a classic case of ‘build first, assess later.’” Parents of schoolchildren protested at the school entrance and voiced dissatisfaction with the authorities’ handling of the matter.

Clash of interests

Days later, a second school in Jiangsu province made headlines after children suffered nosebleeds and itching. The Chengnan Experimental Primary School, in the province’s Hainan county, sits beside an industrial park. Local officials ordered the chemical plants in the park to shutdown production as a result of the publicity.

This is a familiar pattern in China. Action is taken only after serious damage has been caused. The urge to make money and cut corners on safety and people’s livelihoods has been the dominant concern of businesses and local governments. No matter how many statements, plans or anti-pollution “wars” are unveiled by top regime figures such as Li Keqiang, these largely have the character of slogans, but with little real impact. The centre is not in decisive control of the situation as China’s economy is mainly driven at the local level. It is a country “ruled by its mayors”.

In 2015, 20,000 polluting plants were shut down according to government figures and the fines levied increased by more than a third to 4.25 billion yuan. But despite these measures the problems continue and grow. As the Greenpeace study on air pollution shows, a crackdown in one part of the country just pushes the problems to another part of the country.

This underlines the need for democratic control, and the right to set up independent workers’ unions, grassroots environmental watchdogs and other independent popular organisations. Polluting companies must be taken into democratic public ownership to enforce a radical clean up and the necessary investment in green technology. All these needs, which are growing the whole time, clash with the interests of an authoritarian and repressive dictatorship.