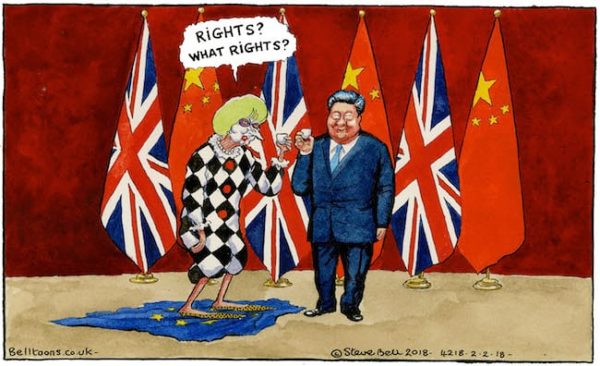

British PM’s visit to China puts business rights before human rights

Vincent Kolo, chinaworker.info

During her three-day visit to China, Britain’s Prime Minister Theresa May avoided irking her hosts with talk of human rights or the recent attacks on democratic rights in Hong Kong.

In so doing May was following in Donald Trump’s footsteps, when he visited China last November, and Emmanuel Macron during his visit earlier this year, although the French president threw in a horse for China’s leader Xi Jinping.

Rather than allowing May’s diplomatic sheepishness to pass unnoticed, the Chinese state-controlled media revelled in it. Beijing’s Global Times hailed her “pragmatism” and said she was right to resist “radical” pressure to engage in “mudslinging” over human rights.

In the days prior to May’s visit, Beijing’s local government in Hong Kong launched new attacks on the city’s partial democratic rights. Three opposition candidates were banned from standing in upcoming by-elections to the Hong Kong legislature. The by-elections are to fill vacancies created by a purge of pro-democracy legislators last year.

Demosisto banned

One of those banned was 21-year-old Agnes Chow Ting of the youth party Demosisto. She was banned on the grounds that the party’s manifesto stands for “self-determination”. This means it’s the party that’s banned rather than one individual. Demosisto won one seat in the 2016 elections only to have its legislator Nathan Law Kwun-chung disqualified along with five others in the “Oathgate” affair.

Demosisto’s secretary-general Joshua Wong Chi-fung wrote an open letter to Theresa May in the Guardian newspaper. He urged her to “use her time with ‘Emperor Xi’ this week to stand up for Hong Kong’s rights, before it is too late.”

British ‘Lords’ Patten and Ashdown, who clearly know a lot about the evils of non-elected office, issued a similar plea. Chris Patten was a former Hong Kong governor and is from May’s Tory party.

“Golden era”

But these calls evidently went unheeded. May stressed a “golden era” of British-Chinese relations, using the slogan of her predecessor David Cameron, whose government signed mega deals for Chinese investment in nuclear power, railways and London’s financial sector. After May’s low-key visit, however, China expert Kerry Brown said relations were in more of a “bronze era”.

The Chinese media, heavy on nationalism, has taken great pleasure in reporting how foreign leaders including Trump, who waged furious attacks on China in his election campaign, have been house-trained by the Chinese dictatorship.

The British government’s loss of worldwide authority is more striking, given that technically it is one of the international guarantors of Hong Kong’s partial autonomy under the Sino-British Joint Declaration of 1984. On his visit to Hong Kong last year for the 20th anniversary of the handover, Xi bluntly stated the Joint Declaration “no longer has any practical significance”.

May’s office in London denied accusations she had failed to raise Hong Kong during her talks with Xi Jinping. It said both leaders had restated their commitment to the “one country two systems” arrangement under which Hong Kong has a degree of autonomy. This is diplomatic waffle! Every attack on democratic rights in Hong Kong is carried out in the name of defending “one country two systems”, so such glib statements from Xi are meaningless and May’s team have knowingly played along.

British government’s silence

During a succession of moves to restrict democratic rights in Hong Kong, screen-out election candidates, introduce new repressive laws and jail opposition activists, many have called on Britain to speak up.

When Benedict Rogers, a senior member of May’s Tory party with an interest in Hong Kong politics, was refused entry to Hong Kong on Beijing’s orders last October, this prompted only a perfunctory protest by the British government. Boris Johnson, the foreign secretary, said he was seeking an “urgent explanation”. Similarly, and more importantly, when Hong Kong bookseller Lee Bo, a British citizen, was abducted by Chinese security agents in 2015 and weeks later resurfaced on Chinese television making a forced ‘confession’, the British government’s response was minimal. The abduction of five Hong Kong booksellers including Lee was used to spread fear in Hong Kong and step up media censorship against critics of the dictatorship.

The Chinese regime feels confident it can step up repression – already the most severe in 25 years – without encountering significant pressure from foreign governments.

May returned from China boasting of 13 billion US dollars in new business deals. Cash comes before human rights, evidently, but even these sums are not impressive by past comparisons. May had travelled with the biggest ever delegation of British business leaders. Britain’s attractiveness as a destination for Chinese capital took a knock after the Brexit referendum and so steadying its relationship with the Chinese dictatorship was the main aim of May’s visit.

One of the deals announced was for luxury carmaker Aston Martin to open more than 20 showrooms in China, worth 850 million dollars. This is irrelevant to the mass of China’s population who will not be queuing to buy an Aston Martin. It would take a Chinese factory worker 22 years, saving their whole salary, to buy the cheapest Aston Martin.

Correct address

Some democracy activists in Hong Kong, China and elsewhere have yet to fully grasp the fact that right wing politicians and governments are not on the same side, they will not and never have fought for democratic rights. Real and effective international solidarity comes from below, from workers, youth, anti-cuts and anti-austerity campaigners, a new generation of left wing feminists, anti-racists and migrant rights advocates. In other words, it comes from the very sections of the population that are battling against the big business policies of Theresa May and Donald Trump. These are the layers the Stop Repression in Hong Kong campaign is turning to.

International pressure is needed to protest the repression in Hong Kong and China. But our appeals need to be addressed to the right people.