Stock market frenzy and fabricated GDP figures cannot hide the reality of an economy in deep trouble

Dikang, chinaworker.info

For China’s one-party dictatorship (CCP), 2015 is turning into quite a dangerous year. After years of rapid debt-driven growth and the world’s biggest construction boom, China’s economy faces a multitude of serious problems. Overcapacity, deflation, a housing slump and local government debt crisis are all acting as a drag on economic growth which by several measures has slowed to a crawl.

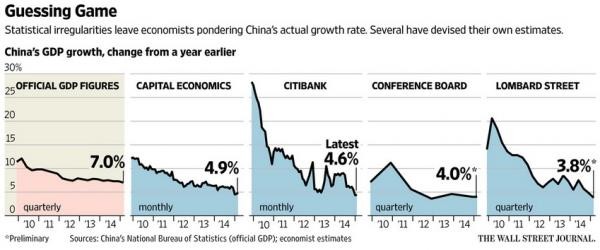

The economy is of critical importance for any government but especially for the Chinese regime which has relied on a combination of fearsome state repression alongside sustained rapid economic growth to maintain itself in power. From 1980 to 2012 gross domestic product (GDP) growth averaged 10 percent per annum. Last year an official GDP growth rate of 7.4 percent was recorded, and this year the target has been lowered to “around 7 percent” – a goal that even Premier Li Keqiang admits will “by no means be easy”. But to make matters worse these GDP figures are almost certainly fake, with today’s real level of growth substantially lower. Some economists warn that China is now already in or dangerously near to a hard landing which is defined as a drop from “a double-digit rate to a growth pace in the low single digits”.

This is what lies behind the recent hasty series of monetary loosening policies, tax cuts, and other stimulus measures, that seemingly reverse the government’s earlier monetary tightening designed to ‘deleverage’ i.e. wean the economy off its addiction to debt. The ruling Politburo’s meeting at the end of April added to indications that a u-turn is being executed with the regime’s much hyped restructuring and reform taking a back seat in the short-term to stimulus measures even at the cost of aggravating already serious debt levels. The People’s Daily, reporting on the meeting, said the government would “likely resort to old means” – referring to more state investment and further measures to stimulate the slumping property market.

Since November, the government has twice cut interest rates, and twice cut the so-called required reserve ratio (RRR), the amount of cash that banks must keep, which is a way to inject extra capital into the banking system. More loosening measures are expected and there is growing nervousness in government circles. “Beijing may not be pushing the panic button, but they appear to be making sure it is working properly,” commented Christopher Balding on financial website Seeking Alpha. This time last year, China’s leaders were more sanguine about the slowing economy, telling us this was by design and would assist an economic rebalancing from excessive levels of investment towards more sustainable growth based on consumer spending. Now, however, both consumption and investment are stalling, along with just about everything else – the ‘controlled slowdown’ and ‘rebalancing’ appears to have derailed.

The two cuts in RRR, in February and April, mean that around 1.8 trillion yuan (US$300 billion), which is no small sum, has been pumped into the banking system in the hope this will flow into increased investment and housing sales. To date this has not happened, and clearly this is the background to the Politburo’s April ‘u-turn’. Housing construction and industrial capacity are already at saturation levels, and profits are tumbling, leading to reluctance on the part of major companies to invest even if credit becomes cheaper.

The April RRR cut by the People’s Bank of China (PBoC), on Sunday 19 April, just 48 hours after new rules announced by the stock market regulator triggered sharp falls in Chinese stock market futures in the US and other overseas markets, seemed to be timed to shore up the market when the Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges opened on Monday morning. This is the first known occasion that the government and central bank have intervened so directly to save the stock market.

Stock market hysteria

China’s major commercial banks, ostensibly controlled by the CCP, are refusing to direct the extra cash to where the government wants it. Instead most of the extra liquidity is flowing into the stock market, which has surged by 80 percent in the past six months. Small traders are flooding into the market with four million new trading accounts opened in the last week of April alone. Around 40 percent of shares are now bought on credit and people are selling their homes to join the stock market ‘gold rush’. According to economist Andy Xie, more than 2.5 trillion yuan of loans has poured into the stock market. Whereas China’s debt crisis is the result of huge stimulus policies to build infrastructure and housing, much of it wasted, today’s stimulus policies are creating nothing but fictitious wealth on the stock market. The regime has encouraged the stock market hysteria through relaxing regulatory controls (a limit of one trading account per person was lifted on 13 April, the latest of several loosening measures) and a massive media campaign. But it is now clearly jittery over the gigantic scale of ‘margin trading’ (buying shares on credit) while fearful that a clampdown could precipitate a market crash, which given the fragile state of the wider economy could tip China into a full-blown recession.

For the CCP, a booming stock market is seen as desirable, despite its obvious dangers, partly to cushion the blow of the burst property bubble, but also to develop equity markets as an alternative source of financing for credit-starved businesses, especially private businesses. These companies are currently dependent on the shadow banking sector, which Beijing is attempting to rein in due to the huge risks it poses to the wider financial system. But government policy is hopping from frying pan to fire and back again – the share market rally is draining liquidity from the banking system as savers withdraw funds to join the gambling binge, thus forcing the central bank to take further easing measures to prevent a liquidity crisis.

According to updated estimates from the Forbes China Rich List, the number of dollar billionaires and billionaire families surged from 242 in October 2014, to 400 in April. On average this means more than 25 new billionaires per month have been created in China in the past half-year as a result of soaring share values. Meanwhile the increase in wages this year is forecast to be the weakest for a decade and strikes are proliferating.

This lays bare the class nature of the economic reform measures of President Xi Jinping and Premier Li Keqiang which, in common with the policies of capitalist governments worldwide, protect the corporate sector while putting the burden of the deepening crisis onto the backs of the working class. Finance Minister Lou Jiwei, one of the most openly neo-liberal top officials, issued an unusually public warning in a speech on 24 April saying China has “a 50 percent chance of sliding into the middle-income trap within the next five to 10 years,” and urging a more radical shake-up of labour laws to make it easier for bosses to fire workers. The middle-income trap is a concept popular at the World Bank, which refers to countries that attain a certain level of development but then become stuck; examples include South Africa and Brazil. Lou’s speech has been widely debated on internet as an example of the new attacks upon the incomes and legal protection of workers and farmers that the government is deliberating.

The soaring stock market is clearly divorced from economic fundamentals and will crash at some point. The shares of People’s Daily, the CCP’s main propaganda mouthpiece, have risen 67 percent in the past six months for example. Stocks on ‘ChiNext’ – China’s version of Nasdaq – are trading at twice the levels of Nasdaq stocks on the eve of the US dotcom crash of fifteen years ago. Several commentators have pointed out that a stock market bubble often marks the final phase of a credit-fuelled economic boom as was the case in Japan in 1989, and – more chillingly – the United States in 1929.

In a recent report, BNP Paribas said, “The Chinese equity rally has little to do with macro-fundamentals and almost everything to do with a self-feeding, leverage-fuelled, retail-buying frenzy.” The bank’s report warned, “But the longer the stock market rally continues, the bigger the correction is likely to be. The stock market bubble powered by margin debt cannot keep inflating, but the Chinese authorities increasingly cannot afford to let it burst.”

7 percent, really?

The regime uses the phrase “new normal” to describe the economic slowdown. The key word here is “normal” – lest anyone should think Beijing is losing control over the economy. The degree of control is debateable, however, and it is more accurate to say the regime is reacting to a succession of shocks and nasty surprises, often being forced to perform policy zigzags, as the economy is pulled deeper into deflation as a result of staggering levels of overcapacity, and debt levels that act to nullify the effects of new stimulus.

For the Chinese regime, the annual GDP target is the single most important figure that exists, upon which much of its credibility rests. But the official data is now widely viewed as fraudulent. “There are also suspicions the shortcomings involve wilful doctoring rather than data collection problems,” commented the Wall Street Journal. A rumour is gaining currency that, like factory bosses who want to cheat the authorities, the government keeps “two sets of books” – one for public use and another purely for internal use that give the real picture and allow it to more accurately calibrate policy.

Kevin Lai, senior economist at Daiwa in Hong Kong, told Reuters, “If you look at Q1 [Jan-March], exports were poor, industrial production was poor, FAI [fixed asset investment] was much slower, retail sales soft, so how can GDP in real terms still be 7 percent?”

If we adopt the “Li Keqiang Index”, so named because the Premier once said that he based his assessment of economic growth on statistics for rail freight, electricity usage and bank lending, which provide a more reliable guide than official GDP figures, then real growth is substantially below 7 percent. Electricity usage in Q1 for example grew by just 0.03 percent from a year earlier, the weakest growth since late 2008, when China was hit by the global financial crisis. Even the government’s measures to improve energy efficiency and curb polluting industries, cannot explain why electricity usage has plateaued – this suggests a sharp slowdown in the wider economy. Even more dramatically, rail freight volumes actually contracted by 9 percent in the quarter.

Consultancy firm Fathom in London analysed China’s Q1 growth based on Premier Li’s three criteria and suggests growth is running at closer to 3 percent than the official 7 percent. “China is in a hard landing now,” Erik Britton of Fathom told the Guardian newspaper (13 April 2015).

Housing slump

China’s housing market and investment in real estate have been the main pillar of economic growth – even more important than exports – over the past seven to eight years. The dramatic slowdown that began last year is not only depressing demand for steel, cement, construction equipment, and a host of other former boom industries, but threatens a wave of financial defaults among overleveraged property developers and the shadow banking ‘investment products’ connected to them. Half of all China’s loans are linked to the property sector. Even if the housing market stabilises at a lower level – which is the most optimistic outcome from the government’s latest rate cuts and stimulus policies – this will exacerbate the problem of industrial overcapacity and stress within the financial system.

China’s housing slump is already inflicting enormous collateral damage on the global economy especially for mineral exporters such as Australia, Brazil, Chile and a host of African countries. Whereas China consumed 12 percent of the world’s metals in 2000, this rose to almost 50 percent over the past few years. Property investment has grown by an average 20.2 percent per year since 1998, twice as fast as China’s overall GDP, but this slowed to just 8.5 percent growth in the first quarter of 2015.

The current property downturn is the most serious since the market was created with the mass privatisation of housing in 1998. House prices have fallen by an average of 6 percent in the past year, following years of double-digit increases. Housing sales fell at an even sharper rate, by 9.1 percent in Q1. Even more dramatic is the slump in land sales by local governments, which fell 32 per cent in the first quarter compared to the same period a year ago. Property developers are pulling back, already saddled with several years’ worth of unsold housing inventory. According to Zhiwu Chen in Foreign Policy magazine (30 April 2015), “At the end of 2014, China had around 75 billion square feet of new property space either under construction or ready to be occupied; even if demand were to remain steady, it would likely take more than five years to sell all that space.”

Land sales have played a crucial role in keeping local governments solvent, accounting for 46 percent of local government revenue last year. The real estate slump therefore threatens to unleash a chain reaction of company defaults and give a new twist to the already severe debt crisis of local governments. The combined debt of local governments was 17.9 trillion (around US$3 trillion) according to the last official audit in June 2013. A new audit has been delayed with Beijing ordering local governments to “do it again” because it felt some of the reports were falsified. Caixin magazine, whose reports are regarded as credible, said the true level of local government debt could now be 40 trillion yuan (US$6.4 trillion).

The Financial Times (12 January 2015) reported that local governments have resorted to buying land from themselves, via the investment vehicles they control – thus taking on more debt in order to cover budget shortfalls. These ‘fake deals’ are a desperate attempt to maintain land prices, because falling prices will have severe knock-on effects for local governments making debts harder to service and new loans harder to acquire.

This compounds Beijing’s policy dilemma, as it attempts to balance between deleveraging, while maintaining sufficient economic growth to prevent an uncontrollable wave of defaults that could trigger a financial crisis. The state-owned banks are increasingly following their own agenda rather than the government’s. A report by Reuters (20 April 2015) showed that none of the major banks have passed on Beijing’s recent policies to support the property market, which include cheaper mortgage rates and more generous lending rules for second home loans. The banks clearly do not have confidence that house prices will rebound in the short-term. “Banks look for good investment return, so they’d rather invest in the stock market,” a Shenzhen property developer told Reuters.

Debt trap

chinaworker.info and the supporters of the CWI in China have long warned that the current economic crisis is not simply a slowing economy or a cyclical adjustment, but the onset of an intractable crisis with China replicating many of the features of Japan after its property and financial bubble collapsed in the early 1990s. This condemned the world’s then number two economy to decades of low growth, deflation (which magnifies debt repayment problems), and ‘zombie’ companies (which subtract value from the economy because their debt costs are so high). Such a situation already exists in some regions and some sectors of China’s economy.

China initially appeared to escape the gravitational pull of the global recession in 2008 and, through an unprecedented debt-financed stimulus package, powered back into double-digit growth rates. In so doing it also helped pull the global capitalist economy back from the brink of a 1930s-style depression. But what goes around comes around, as the saying goes, and the debt run-up accumulated from four years of mega stimulus (2009-12) and its aftermath, now weighs down upon the Chinese economy like an incubus.

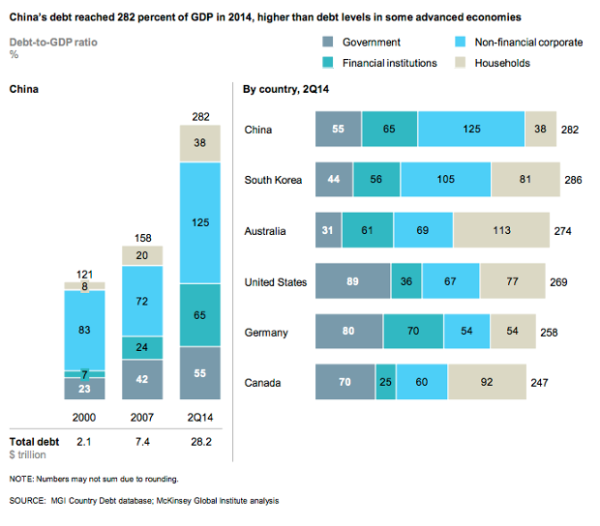

China’s debt has quadrupled in seven years from US$7 trillion in 2007 to US$28 trillion in 2014, according to a February 2015 report from McKinsey & Co. This put China’s debt-to-GDP ratio at a staggering 282 percent, higher than the US and Germany. Apologists for the CCP’s policies during this period argue that China, “got its money’s worth” with new cities, expressways and bullet trains, whereas the post-2008 stimulus policies carried out by Western capitalist governments mostly went into financial speculation. While socialists are unequivocally in favour of socially necessary infrastructure, housing and urban development, we point out that what has actually happened in China is a far cry from the rosy picture the regime has painted. A study published last year by Chinese government researchers found that US$6.8 trillion worth of investments – fully 37 percent of all investment in China since 2009 – were wasted.

A succession of ‘vanity projects’ – to burnish the image of the regime or its local representatives – have consistently overshot their budgets due to bribery and embezzlement, overpricing of inputs and poor planning. The Three Gorges Dam overshot its budget by 100 percent and the Beijing-Shanghai high-speed railway by 139 percent. China’s railway network expanded by 21 percent in terms of track kilometres between 2005-10, with a 45 percent rise in passenger numbers. But this required a 518 percent increase in investment in the same period. Private contractors who performed most of the construction work engaged in rampant overpricing. Caixin reported that suppliers were charging 30,000 yuan (US$4,800) for a single chair for a high-speed train. The Shanghai-based company that became the main supplier of seats on China’s bullet trains, “set prices that were three times those charged by other manufacturers,” reported Caixin. This helps to explain how the former rail ministry accrued debts of 2.2 trillion yuan (US$354 billion) – greater than the total debt of Greece.

Overcapacity

Today the economy is dealing with the blowout from this debt-driven stimulus. There is overcapacity in every direction. China produces half the world’s steel (822 million tonnes in 2014) but its idle capacity of more than 200 million tonnes is the equivalent to double the US yearly output. Steel output fell by 3.4 percent last year, the first contraction in 30 years, and there are projections of a 10 percent fall this year. The outlook for the auto industry, also the world’s biggest, is similar. This year, China’s auto factories will be able to make 10.8 million more vehicles than will be sold. The idle capacity is equivalent to “two Japans” (Japan sold 5.5m vehicles in 2014).

Overcapacity has brought with it deflation, with factory prices falling continuously for the past three years and at a faster pace this year. China’s official producer price index (PPI) fell 4.6 percent in March. Deflation and ‘lowflation’ afflict many parts of the global economy, especially Europe and Japan, and these deflationary pressures will be amplified if China decides to export its way out of deflation by devaluing the yuan and joining the ‘currency war’.

Devaluation creates inflation at home by increasing the cost of imports such as commodities, while passing on the deflationary pressure to other economies as the price of Chinese goods fall on the global market. So far the Chinese regime is resisting this temptation not least because of its drive to internationalise the yuan or ‘redback’, as part of a longer-term strategy to challenge the supremacy of the dollar or ‘greenback’ in the global financial system. For this, and other international ambitions to be realised, Beijing needs to maintain a stable currency. The deepening crisis, however, could force it to throw these considerations overboard and opt for devaluation, although even this, a policy that would lead to increased protectionist clashes especially with the US and Europe, is also fraught with difficulties.

Allowing the yuan to drop against the dollar would accelerate capital flight from China, which has hit record levels in the past two quarters. According to Barclays Bank, China’s capital outflow is double that suffered by Russia last year under the impact of US-led sanctions. Barclays estimate that around US$300 billion has exited China in the past 12 months (more than three times the official figure), mostly to take advantage of the surging dollar and expected increases in US interest rates. Devaluation, leading to increased capital flight, could force the government to impose much tougher capital controls – reversing its current and planned liberalisation measures – which in turn could spark financial panic and bank runs as global and Chinese capitalists recoil in horror.

Historic crisis

China’s dilemma underlines the insanity of the current economic system, because production and investment are not geared to meet the needs of society, but to turn a profit. China’s market cannot absorb what its factories and construction sites produce because the majority of people cannot afford these things. Migrant workers, who number around 260 million today, are crowded into makeshift accommodation and almost half of them live on construction sites or in factory barracks. At the same time there are an estimated 49 million empty apartments in China.

The CCP believed it could ‘game the system’ of capitalism using state intervention, loans from state-owned banks and government contracts, to generate fantastic profits for a tiny party-connected elite while avoiding the downsides of capitalism in the form of a crisis of overproduction. The stimulus of 2009 was hailed as a ‘marvel’ by the whole world, but it has led the economy into an impasse with the CCP leaders themselves now concluding that the old ‘state capitalist’ model has reached the end of the road. Given their rejection of socialism, which is of course anathema to the billionaire families who now dominate the CCP regime, the regime has come up with no other alternative than a variant of the neo-liberal market policies practised by Western capitalism, while not relinquishing a centimetre of authoritarian control.

It is the financial sector where Beijing is preparing the most radical neo-liberal ‘reform’. This is another reason why it appears to have given carte blanche to the stock market speculators, while also stepping up plans for an expansion of bond markets and opening the banking sector to private capital. The growth of online banking, dominated by non-state internet companies like Tencent and Alibaba, is another feature of this process, as is the recent announcement by Li Keqiang about lifting restrictions on foreign loans via banks based in the four recently established free trade zones (Guangdong, Fujian, Tianjin and Shanghai). The liberalisation of the financial sector, and parallel moves to liberalise the yuan’s capital account, are intended to exert competitive pressure on the state-owned banks and make capital allocation more market-based and profitable. This also affords opportunities for many of the CCP’s elite ‘princeling’ families who are already ensconced in the world of high finance to further enrich themselves and legitimise their ill-gotten wealth.

‘Belt and Road’ strategy

On 1 May, the regime’s long-awaited deposit insurance scheme came into effect. This covers bank deposits of up to 500,000 yuan (US$80,700), similar to arrangements in many other countries. In China’s case, however, this marks the end of the implicit government guarantee to bailout any failed financial institution (because these are invariably owned by or connected to one or another unit of the state). With the new scheme in place Beijing is expected to allow financial defaults to occur on a much greater scale providing they are deemed to be peripheral to the wider economy, while continuing to rescue banks and companies that are deemed “too big to fail”. This delicate balancing act is intended to instil discipline in the financial sector, to curb shadow banking excesses and facilitate deleveraging. But clearly it entails huge risks especially given the murky nature of shadow banking which now accounts for a third of all loans in the economy, with the potential for miscalculations and further nasty surprises ahead.

At the same time Xi Jinping is pushing ahead with a raft of ambitious regional and global initiatives that aim to project China’s financial might, as an increasing challenger to a US capitalism that is in retreat, but also to provide new markets for China’s unwanted cement, aluminium, steel, and other heavy industrial production, which is fuelling deflation at home. That is the significance of the Silk Road Economic Belt and Maritime Silk Road projects, known collectively as the ‘Belt and Road’, which aim to promote massive infrastructure projects linking Asia to Europe and Africa. It includes plans for expressways, high-speed rail links, oil pipelines and ports – and even a tunnel under Mount Everest – to be built mostly by Chinese corporations and funded mostly with Chinese capital and loans.

Through this strategy Beijing hopes to tie its regional neighbours into closer dependence on Chinese capitalism and block US attempts to undermine its influence. An important additional aim of the ‘Belt and Road’ strategy, and the new regional banking entities that China is creating to back it up, such as the AIIB (Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank), is to increase the use of the yuan in global finance, which is a precondition for Chinese capitalism to free itself of the need to ‘kowtow’ before the dollar. Because the dollar is the main reserve currency, accounting for 65 percent of all the reserves kept by governments around the world, the US has a unique ability to decide its own economic path and impose its terms upon other governments.

Thus the internal contradictions in the Chinese economy, the nightmare of a ‘Japanese perspective’ and the risk of massive social upheavals if the economy stagnates, are propelling the Chinese state into a ‘Great Leap Outward’. This will inevitably lead to intensified global and regional rivalries and conflicts. In the past, China’s rapid economic expansion was absorbed and facilitated by global capitalism due to exceptional conditions in the immediate aftermath of the collapse of Stalinism in Russia and Eastern Europe and the rapid (although inherently unstable) development of Asian capitalism. But today the global pie of capitalism is not expanding, but rather shrinking, and the struggle for each portion can only intensify among the rival ruling groups. Only the working class in China and internationally, by organising around a socialist alternative, can put an end to the economic destruction of capitalism, which is preparing new crises and international calamities.