What are the political differences between anarchism and marxism, and do they still matter in the new international situation?

Vincent Kolo, chinaworker.info

There are areas of common ground between anarchism and marxism – in opposing bureaucracy, for example, and in seeking the destruction of the capitalist state, in contradistinction to reformists who want gradual change within the existing state. But there are also important differences between marxism and anarchism on questions of theory, programme and methods.

Marxists and socialists cooperate with anarchist groupings in many day-to-day struggles, for example against fascist parties, or within the broader international movement against capitalist globalisation (such as the anti-G8 or the coming anti-APEC protests in Australia). But their lack of political clarity over the role and tasks of the working class in the struggle against capitalism invariably leads the anarchists to make serious political mistakes.

This issue has become more relevant in recent years as a result of the brutal forward march of globalised capitalism, which accelerated enormously after the collapse of the Stalinist bureaucrat-planned economies nearly two decades ago. These processes led to an unprecedented swing to the right of the old parties that formerly stood – in words – for ‘socialism’ or ‘communism’, and also to record levels of passivity from the trade union leaders who in many cases are tied to, or even part of, the leadership of these parties. This process is global, effecting parties from Labour in Britain to the ex-Maoist ’communists’ in India – parties that previously reflected the mass pressure of workers and other oppressed layers but have since been ’bourgeoisified’, unreservedly serving the interests of the capitalists. This means that today, socialists and worker activists face very complex problems in respect of how to organise – much more complex even than in Lenin and Trotsky’s day. This does not mean we marxists are pessimistic about the tasks ahead, but we nevertheless have to recognise this reality in order to go forward.

For anarchists the explanation for the betrayals of the former workers’ parties is simple: all political parties are inherently evil and corrupt! But this tells us absolutely nothing about what needs to be done. For the CWI and marxism, which rejects the simplistic and one-sided analysis of anarchism, the task is to rebuild a socialist labour movement including new mass socialist parties, insuring that the lessons of why the old parties degenerated are fully absorbed by a new generation of workers and youth.

1. What is anarchism?

There has been a certain revival of anarchist ideas internationally – but not as an organised movement or coherent body of ideas. Partly, that would be a contradiction in terms given that by nature anarchism is a loose, politically heterogeneous current. Even the anarchist theoreticians Proudhon, Bakunin and Kropotkin themselves were inconsistent – they did not share a common programme or perspective.

The term anarchism comes from the Greek language, meaning ‘without rulers’. There are almost as many types of anarchism as there are anarchists, including right-wing ’libertarians’ or bourgeois anarchists who hate all forms of state regulation but worship the ’market’. Most anarchists, however, sincerely want to fight capitalism. Even so, anarchism lacks a coherent position on most questions – its only consistent element being an idealisation of ’spontaneous’ actions with a minimum of organisational structures and no leadership.

Some European anarchists did not oppose the US-NATO war against Yugoslavia in 1999 (when the US ”accidentally” bombed the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade) arguing the Milosevic regime was racist – against the Kosovo Albanians – and despotical. Both observations are true, but had nothing to do with why US and European imperialism went to war, which was to safeguard their power, prestige and geopolitical interests. Therefore it was the duty of socialists and internationalists to oppose the war, while we marxists also stressed the right to self-determination of the Albanian population in Kosovo in our speeches and written material on all anti-war demonstrations. This example shows the anarchists’ lack of confidence in the working class, resulting in a lack of political independence which leads them to support or at any rate not to oppose other class forces – in this case imperialism. Similarly, in the 1960s many anarchists internationally were full of praise for Mao’s communes and the decentralisation measures of Tito’s Stalinist regime in Yugoslavia.

We find another example of anarchist inconsistencies in the June 2007 issue of the anarcho-syndicalist newspaper ’The Worker’ (Arbetaren) in Sweden, which criticised the ’black bloc’ anarchists at the G8 protests in Germany as ”rioting tourists”. We marxists often disagree with the – chaotic – tactics of the anarchists on such demonstrations, but unlike ’The Worker’ we put the blame entirely on the German police for the violence during the G8 meeting.

These examples show the confusion and lack of consistency that arises from the anarchists’ opposition to party-like structures. This makes collective evaluation and a unified point of view impossible.

2. ”Middle-class socialism”

Having said this, most of the youth who today identify with anarchism are not organised at all. Some are loosely connected – turning out for demonstrations – but don’t stand for a definite ideology. For many of the middle class and student youth attracted to anarchism today it is more an ‘alternative lifestyle’ connected to popular culture, rather than a decision to engage in political struggle. This is part of the appeal of anarchism: unlike marxism, one is not required to build a party, go to meetings, campaign, or engage in any collective activity. You can be an anarchist on your own terms – you ’change’ yourself but not society! To be an unorganised marxist is a contradiction in terms, but the same cannot be said of anarchism.

Marx characterised anarchism as ’petit bourgeois socialism’. It expresses the rebellion of the middle layers, rather than the working class, against the indignities of capitalism, while at the same time harbouring a strong distrust towards the collective discipline of the proletariat and its desire for strong centralised forms of organisation. It is not an accident that traditionally, anarchist and anarcho-syndicalist movements were strongest in the least industrialised countries of Southern Europe and Russia, where peasant habits of thinking were still strong within the young working class.

In that sense, anarchism represents a pre-socialist ideology, from before the era of industrialisation that concentrated the working class in huge workplaces and taught it the need for a collective rather than individual response to the power of the bosses. The leading thinkers of anarchism reflected this fundamentally middle-class perspective with the individual rather than the position of social classes as its focus. One of anarchism’s foremost theoreticians, Bakunin, saw the Russian peasant commune as the basis of a future anarchist-communist society. Anarchist theory does not differentiate between proletarians and middle-class layers like peasants and even small businessmen, arguing that all those who work for the profit of others are members of the working class. This is of course a gross oversimplification and misses the decisive role of the proletariat as the leading force in the struggle against capitalism.

The common denominator is a rejection by anarchism of all forms of centralism whether political or economic, even when these are subject to the democratic control of the working class, in favour of individualism. Marxists are of course for the development of individual personality; we reject the Maoist caricature that everyone must wear an identical uniform. For genuine Marxists there is a dialectical interaction between the role of the individual and the need for a party, collective discipline and a common plan of action, which are determined by the class struggle.

These things flow from the day-to-day experience of the working class in the struggle against capitalism. Having reached a decision to strike, preferably through mass meetings, workers try to insure the decision is supported by all, even those who opposed it. A leadership is elected with various areas of repsonsibility: publicity, fund-raising, contact with other workplaces, picketing etc. Pickets defend and enforce the strike against the police and strike-breakers. This is a basic example of ’democratic centralism’ in action. The marxist concept of a revolutionary party merely developed this idea further as the most effective means to conduct the political struggle for a new socialist society. Marxism prefers to speak with ’one voice’ in order to win the confidence of the working class. But to arrive at a common position of course a healthy culture of debate, criticism and discussion is necessary, something that Stalinism – which posed under the name of ’marxism’ – could never tolerate. The role of a marxist party is to accumulate experience of workers’ struggles and to raise consciousness. This approach is alien to anarchism, which consequently starts from ’zero’ every time it is confronted with new political problems.

3. Direct action

Anarchism espouses ‘direct action’ which is actually nothing more than a normal response of the working class to political attacks, job losses, police brutality etc. The response of the French youth and workers in 2006 to the right-wing government’s attack on young workers (the so-called CPE law) was an example of ’direct action’ by the masses. Today’s anarchists try to imitate this, but not very successfully. Naturally, marxists are in favour of ‘direct action’ by fighting layers of workers, peasants and youth. In recent years we have organised protests and actions on a scale that no anarchist group could match.

In the United States, the CWI section has organised walk-outs involving thousands of school students and students against military recruitment to Bush’s Iraq war. Tens of thousands followed our call for school strikes in Germany, Sweden and Ireland against the Iraq war in 2003. In northern Pakistan in 2005, Socialist Movement Pakistan (CWI) organised emergency relief, field hospitals and temporary schools after an earthquake that killed over 40,000. This relief was financed by workers’ collections in Pakistan and overseas and was linked by CWI comrades to socialist agitation against the incompetence and corruption of the country’s military rulers. In Sri Lanka today, the United Socialist Party (CWI) with small resources and at great risk to our own comrades’ lives, is leading the opposition – organising countless marches and rallies – to the racist government’s war against the Tamil minority.

In Ireland the CWI comrades initiated a campaign against water charges through mass non-payment. This campaign draws on the experience of mass non-payment in Britain against the so-called Poll Tax in the early 1990s, which was led by CWI comrades and resulted in 18 million people refusing to pay the new tax. The result was a spectacular victory and the end of Margaret Thatcher’s political career!

Marxism advocates strikes, occupations, demonstrations, and other forms of proletarian action in the course of a struggle, but unlike anarchists we stress mass action – the need to involve the widest possible numbers through democratic discussion and democratic methods of organisation. While many anarchists would agree with this in words, in practise anarchist ‘direct action’ is reduced to the work of small secretive groups acting with little support, let alone participation, from the masses. This is appealing to a layer that is understandably impatient with the seeming inactivity of many sections of the workers’ movement today. Nevertheless, it can also have negative effects. As Lenin pointed out, ultra-left sentiments are always payment for the opportunism and betrayals of the leaders of the workers’ organisations. This is the case in anti-fascist struggles for example. While marxists stress the need for mass mobilisation and a clear socialist alternative, as the key to stopping the growth of fascist organisations, anarchist groups stress ‘action’ which by its very nature is clandestine (to prevent the police or fascists discovering the plan) and therefore excludes mass mobilisation.

We marxists have debated many times with anarchists over the negative effects of this approach, which is not confined to anti-fascist campaigns. As Lenin and Trotsky explained, the net result of this approach – of a small group substituting itself for the action of the masses – is to lower consciousness. Why should the masses enter struggle themselves, if the answer is liberation by small ’heroic’ groups from outside? Given the role of media and police propaganda, the anarchist concentration on physical confrontation with fascists (even on an individual basis), placing this above the task of mobilisation and political explanation has contributed in some countries to a downturn in the anti-fascist struggle.

Fascist and extreme right groups today are not, as in the 1920s and 30s, an immediate threat to the working class as a whole. They are however a serious threat to individual immigrants, trade unionists, socialists, homosexuals and others whom the fascists want to crush. For this reason, Marxists see it as crucial to campaign against fascist and extreme right parties, to prevent them becoming a bigger threat in the future. The most important way to defeat them is by campaigning for a socialist alternative to capitalism, unemployment, low wages and overcrowded housing – the issues the fascists and racists build their support on. We oppose all fascist marches and meetings, and call for these to be stopped through mass pressure. We don’t call on the police or government to ban fascist marches as we cannot of course rely of the capitalist state in this struggle – it prefers to use bans and repression against the left.

We marxists also stand for well-defended anti-fascist demonstrations with our own stewards, armed with batons etc. – something often opposed by anarchists as ‘bureaucratic’. At the same time, anarchist groups generally tone down any anti-capitalist propaganda in relation to anti-fascist actions, arguing that politics is not so important – stopping the fascists ‘is everything’. This is their approach to other broader campaigns or coalitions, in fact whenever they are called upon to cooperate with others, anarchists tend to adopt an opportunist, non-political stand on most questions, placing all their stress on ’action’.

Here we see a fundamental difference between marxism and anarchism over methods and programme. Marxism stands for an orientation to mass workers’ struggle linked to a clear socialist message, while anarchism stands for ‘actions’ that are not connected to any clear political line or involvement by the working class. There are many lessons here for the situation in China, even if there are obvious differences in a country where at this stage, all public political activity and campaigning etc., is outlawed. Neo-liberal capitalist policies and state repression will only be stopped by mass struggle and organisation of workers, not by small isolated ‘actions’ however well-meaning the initiators are. Chinese workers instinctively understand this as the demonstrations and strikes of recent years show.

4. The state

Anarchism, with its hostility to all forms of state power seems – superficially – to provide an explanation not just for the rottenness of capitalism but also the bureaucratic Stalinist dictatorships that existed in Russia, China and Eastern Europe. Rather than the isolation of the Russian workers’ state in conditions of poverty and backwardness, the Russian Revolution was doomed – in advance – because “all state power corrupts”.

The state was according to Lenin the ”most politically essential issue” dividing marxism from anarchism. Lenin’s ’State and Revolution’ is undoubtedly the marxist work that most confounds anarchists. Some of them argue that Lenin ’stole’ the arguments of anarchism, for example, in calling for the abolition of the standing army in favour of a workers’ militia. On the contrary this and the other conditions put forward by Lenin to prevent the growth of bureaucracy (right of recall over all officials, abolition of privileges – elected representatives on a worker’s wage, rotation of official posts) are entirely in keeping with marxism’s dialectical view of the problem of state power after a successful socialist revolution. The anarchists say the state should be abolished ’at one stroke’. Marxists agree the old state, the bourgeois state, must be completely dismantled but it must be replaced by a democratic workers’ state to prevent the deposed capitalists, with help from international capitalism, launching a new power-grab.

Lenin used the term ’semi-state’ to describe the workers’ state. This is because, as democratic economic planning and socialist methods eradicate class divisions and raise human culture to new levels, the need for a state – a separate organ for the oppression of one class by another – will disappear. Unlike other types of state throughout history, the workers’ state is a transitional formation that will ’wither away’ as a socialist society based on human solidarity develops.

This of course did not happen in Russia after the 1917 revolution because of the isolation of the new workers’ state in an economically backward and war-ravaged society. The reason for the perversion of Stalinism – of a parasitic elite emerging upon the state property forms created by the workers’ revolution – was the delay of the revolution in the advanced capitalist countries of Western Europe and the United States. This is also the reason for the temporary expansion of Stalinism to China, Eastern Europe and other countries in the 1940-80s. The bureaucracy, as we know, were unable after their initial successes to develop the planned economy, which then collapsed with most of the bureaucrats transforming themselves into property owners and capitalists. In the process they did enormous damage to the name of socialism and marxism, which they used to cover their crimes. The resulting anti-socialist backlash dominated the decade of the 1990s, but has already begun to recede, with the ideas of socialism destined to make a powerful comeback in the new era that is opening.

However, given the experience of Stalinism and its effects on consciousness, marxists today would not use Marx’s term ’dictatorship of the proletariat’, because it can identify socialism in the minds of workers with Stalinist or Maoist one-party dictatorship. Today, the concept of a workers’ state can best be summarised in the term ’workers’ democracy.’

5. Lessons of anti-capitalism

The global anti-capitalist and anti-corporate movement is influenced by semi-anarchist ideas, particularly the anti-party prejudices of anarchism. This is firstly because the establishment political parties, including most of the so-called workers’ parties, are outside the movement and even hostile to it. It is not strange then if a layer of youth and even workers regard political parties as ’old fashioned’, looking instead to broader, looser campaigning networks and social forums.

Despite such complications, we marxists play an active role in a variety of anti-capitalist networks, single-issue campaigns and forums. The CWI has initiated many such campaign networks – against racism, against war, against privatisation, for women’s rights – and succeeded through such networks in mobilising broader layers of workers and youth in struggle than otherwise would have been possible. But we don’t counter-pose such temporary campaign formations to the need to build mass socialist parties. In contrast to the anarchists (and even some who claim to be marxists) we combine the immediate needs of the class struggle with preparing the long-term interests of the proletariat.

As we have explained in other CWI material, the movement against capitalist globalisation is not at this stage a clearly proletarian movement. In most countries the trade unions play almost no role, while non-government organisations (NGOs) occupy an artificially big place in deciding the ideas, campaigning methods and slogans of this movement. Despite the weakness of organised working class involvement at this stage, we marxists play an active part – to do otherwise would be sectarian.

We see this movement as an anticipation of a future mighty wave of workers’ struggle and political – i.e. socialist – revival on a world scale. Marxists therefore participate actively, mobilise for demonstrations while at the same time arguing for an explicit socialist alternative to capitalism and its agencies like the IMF, G8 etc.

In the anti-WTO protests in Hong Kong in 2005, for example, the CWI group were alone in openly campaigning against capitalism, not just against the WTO and neo-liberalism (read the CWI leaflet here http://www.chinaworker.org/zh/content/news/85/). All the other marxist groups in the Hong Kong anti-WTO protests kept to the ’official’ NGO-approved slogans such as ”Another world is possible”. Rather than use this extremely vague slogan, the CWI contingent in our material used the slogan ”A socialist world is possible”.

Likewise at the anti-G8 protests in Scotland 2005 and Germany 2007, big CWI contingents made a point of distinguishing ourselves from the pro-establishment ”Make Poverty History” campaign of the Christian Church, NGOs and rock stars that was even supported by Tony Blair! We put forward the slogan ”Make Capitalism History” and our contingent marched in red while others, including other left groups and anarchists, donned the official white colours decided by the Church and NGOs.

The experience of this movement is a crushing answer to the anarchists’ arguments against a working class party, on the grounds that the party is the source of bureaucratism and bourgeois influence in the working class.

Despite its loose, non-party character, the movement against globalisation has nevertheless thrown up a de facto leadership of intellectuals and celebrities. Some of the leading figures of this movement, like Naomi Klein, Susan George and Walden Bello, make very good, penetrating criticisms of neo-liberalism. But inevitably because they are not under the democratic control and accountability of an organised mass membership they also make mistakes and succumb to the political pressure of capitalist ’public opinion’. After 9/11 Susan George, who is a leading spokesperson for the campaign organisation ATTAC, made statements in support of the US war in Afghanistan, for example, while Walden Bello, who heads the anti-WTO grouping Focus on the Global South, argues, quite incorrectly, that CCP ’reform and opening’ policies have been tougher against foreign capital than other East Asian states, implying this is a model for others to follow!

6. Universal suffrage

Anarchists are ’abstentionists’ and oppose all participation in elections. Bakunin agreed with Proudhon’s maxim that, “universal suffrage is counter-revolution”. This, by the way, did not stop Proudhon later becoming a politician in the French National Assembly! Marxists agree that bourgeois ‘democracy’ is used by the rich to maintain their power, while the poor majority are duped into believing they have a say. We are not ’parliamentary cretins,’ to use Lenin’s famous term, but understand that workers must build their strength outside of parliament because the capitalist system cannot simply be voted out of existence.

As Trotsky put it, ”the capitalist class can rule by counting heads or by breaking heads!” – in other words, when their power, profits or money-making ’stability’ are threatened, the capitalists are prepared to dispense with the trappings of bourgeois democracy and shift to authoritarian rule, as we saw in Thailand just last year. Without illusions therefore, we marxists stand for the formation of workers’ parties and active campaigns for socialist politics in elections. In contrast to anarchists, we use election campaigns to raise political consciousness among the masses, build support for socialist ideas and win not just votes but also active adherents to the struggle.

Particularly in China, including the Hong Kong SAR, an anarchist ‘abstentionist’ position would be catastrophic for any group that wants to build support among the working class in the period ahead. China is on the threshold of a mass awakening of democratic aspirations. There will be big illusions that ’democracy’ can solve all problems – pollution, corruption, inequality and oppression. Marxists warn that unless capitalism is overthrown, nothing fundamental will change and these problems will continue even under a ’democratic’ government. But we do not say this from the sidelines – dismissing universal suffrage as ’counter-revolution’. We engage in the struggle.

Marxists are the most energetic fighters for democratic rights such as the right to strike, to set up trade unions and political parties, for free elections and an end to one-party rule. We are, to use Lenin’s phrase, ’consistent democrats’, meaning that we go much further than the spineless bourgeois democrats for example in Hong Kong. They try to reassure the CCP leaders and the tycoons that Hong Kong will be ’safe’ under a system of universal suffrage. The bourgeois democrats assure them they will not threaten the tycoons’ super-profits nor will they attempt to spread ’democracy’ beyond the SAR to the mainland. We marxists argue the exact opposite – we say one-person-one-vote must be linked to a struggle for real change on behalf of the working class majority, and not just in Hong Kong! We demand the right to vote at 16 years, votes for migrant workers, and the replacement of Hong Kong’s rubber-stamp Legislative Council with a truly accountable people’s assembly with powers to enforce an 8-hour working day, decent minimum wage, reverse privatisations and take the major companies and banks into public ownership.

We criticise the pan-democrat leaders’ strategy of half-yearly or yearly parades as not going far enough. We stand for: “A workplace campaign to mobilise the full strength of the working class behind demands for democratic rights now! For a one-day general strike, linked to demonstrations and mass meetings, as a first step.” [For full democratic rights – no backsliding! 30 December 2005, chinaworker.info]

7. Struggle for democratic rights

This approach, linking far-reaching democratic demands to demands for the overthrow of capitalism, is what Lenin meant by, “the inseparably close connection between socialist and democratic propaganda and agitation, to the complete parallelism of revolutionary activity in both spheres.” [Lenin, The Tasks of the Russian Social-Democrats, Collected Works Volume 2].

This general approach applies to the mainland, not just Hong Kong. Marxists advocate workers’ democracy – direct democracy based on elected workers’ and peasants’ councils or ’soviets’ – which is far more democratic than the most democratic parliament. But the demand for soviets cannot be raised all the time regardless of political conditions. It is in periods of revolutionary struggle that the working class and other oppressed layers will respond to such a call. Trotsky criticised the idiocy of the Stalinists in 1928 in launching the call for ‘soviets’ after the crushing defeat of the revolution in China. They had refused to agitate for soviets during the upturn of 1925-27, but to cover themselves with a radical image afterwards, they opposed the slogan of a Constituent Assembly in favour of a wholly unrealistic and empty call for ‘soviets’. Trotsky explained:

“The stage of democracy has a great importance in the evolution of the masses. Under definite conditions, the revolution can allow the proletariat to pass beyond this stage. But it is precisely to facilitate this future development, which is not at all easy and not at all guaranteed to be successful in advance, that it is necessary to utilize to the fullest the inter-revolutionary period to exhaust the democratic resources of the bourgeoisie. This can be done by developing democratic slogans before the broad masses and by compelling the bourgeoisie to place itself in contradiction to them at each step.

”The anarchists have never understood this Marxist policy. The opportunists [i.e. the Stalinists – Editor], mortally frightened by the fruits of their labour, do not understand it either. But we, thank heavens, are neither anarchists, nor opportunists covered with shame, but Bolshevik-Leninists, that is, revolutionary dialecticians who have understood the meaning of the imperialist epoch and the dynamic of its abrupt turns.” [Leon Trotsky, China and the Constituent Assembly, December 1928]

The struggle for democratic demands and the need to link these to the struggle against capitalism, which in China is intertwined with the CCP dictatorship and police terror, is a crucial task for the new generation of fighting workers and youth. Democratic demands have already surfaced to a limited extent in the course of recent struggles against forced eviction (Shengzhou and Hohhot), against pollution (Xiamen and Wuxi) and during strikes for example in the Pearl River Delta. If revolutionaries were to adopt the crude abstentionist and anti-party outlook of anarchism, they would cut themselves off from what will inevitably become the main process of political awakening in China. Not only would they be left on the sidelines, they would surrender the field to assorted nationalists, rightists and other pro-capitalist forces posing as ’democrats’.

8. New workers’ parties

Anarchist groups play no role in electoral struggles. This means they exclude themselves from an important field (it is not the only field) of the class struggle. In many countries serious efforts are being made by workers, socialists and rural activists to break the political monopoly enjoyed by neo-liberal capitalist parties. New left formations – sometimes parties, sometimes looser electoral alliances or blocs – have been launched in several countries, anticipating an even bigger movement in this direction in the future. In Brazil, Belgium, Germany, Nigeria and Scotland, the CWI sections have helped to initiate and build new left formations.

Given the confused consciousness of many – even combative – sections of the working class, it is unlikely that new workers’ parties or left formations will start out with a fully rounded-out socialist or marxist programme. The approach the CWI has adopted is that of Marx when he said, “A step forward in the real movement is worth ten programs”.

This does not mean that we take issues of programme and policy lightly. CWI comrades argue consistently for the adoption of clear socialist policies which will strengthen these new formations. We reject the arguments of some left groupings, including some so-called Trotskyists (the IST for example), that a socialist profile is a handicap that “scares people away”. But we do not argue our case in an ultimatist fashion, of making our contribution conditional on a full socialist programme being adopted. As in the struggle for democratic rights, marxists show by our actions, by results, that there is no contradiction between building broad support for struggle and popularising socialist policies.

We point out that unless the lessons are learnt as to why and how the Social Democrats and Stalinists became transformed into capitalist parties, the same fate awaits these new formations, only more rapidly in the era of capitalist globalisation, which has squeezed the space for any kind of national, reformist policy. New left parties must embrace a clear socialist alternative, operate on democratic lines allowing complete freedom of tendencies, and orientate to class struggle to avoid becoming dependent on electioneering. The elected officials of these parties must ’practise what they preach’ and live on a worker’s wage without privileges. Unless this is done then even today’s nascent left parties and formations can become bureaucratised, paper constructions, lacking an active working class membership, which under the pressure of the bourgeoisie will inevitably be pushed to the right.

The CWI has considerable experience from electoral work on five continents. From 2002 when we had 11 elected city councillors, we now have 36 in Australia, Britain, Germany, Ireland, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Sweden – all elected as marxists and ‘workers’ representatives on a workers’ wage’. We have used these elected positions to mobilise for struggle outside the ’parliamentary chamber’ – to spread socialist ideas and expose the corruption and pro-capitalist nature of other parties. This work has been conducted in the same tradition as Lenin and the Bolsheviks who even sent representatives into the Russian Tsar’s rubber-stamp Duma, to use this as a platform from which to agitate for socialism.

Clearly, anarchism is diametrically opposed to marxism on this vital question, which boils down to: How to win the ear of the working class? Most workers in the bourgeois ’democracies’ still look to the parliamentary arena to solve their problems, even if this is increasingly for negative reasons – to vote to keep out or punish the most corrupt gang of politicians. It would therefore be a big mistake to boycott this arena – as the anarchists do –and leave the field exclusively to bourgeois ideology, which anyway completely dominates the media, public debate and popular culture.

In 1986, the Maoist Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) allowed itself to be cut off from the mass movement against the Marcos dictatorship. Because the CPP incorrectly saw the rural military struggle as primary, they neglected the urban movement that actually overthrew Marcos. In the elections that accompanied this revolutionary upsurge, the CPP played no role, surrendering the field to the bourgeois democrat Aquino. While the CPP’s line flowed from a Maoist ’peasant war’ perspective rather than an anarchist perspective, the net effect was strikingly similar – this party’s strength was decimated as a result of missing these revolutionary opportunities.

There are instances when it is correct to boycott elections, but not as a passive gesture, rather as part of an active offensive against the capitalists. Trotsky argued, “As a general principle, a revolutionary party has the right to boycott parliament only when it has the capacity to overthrow it, that is, when it can replace parliamentary action by general strike and insurrection, by direct struggle for power.” [Trotsky, Once Again: The ILP, February 1936]

Kropotkin attacked the British followers of Marx and Engels who played a pioneering role in the late 1800s in building the Labour Party and fielding trade union candidates in elections. He described this as “abominable tactics… of arraying at election times all their forces against the radicals and the liberals, which was equal to supporting the conservatives…” [Peter Kropotkin, Words of a Rebel, 1885].

Kropotkin used exactly the same argument that the US Democratic Party uses today against ’third parties’ on the left, claiming this is ’equal to supporting’ the Republicans. The CWI section in the US, Socialist Alternative, gave critical support to Ralph Nader as an anti-war, anti-corporate candidate in the 2000 and 2004 presidential elections. We do not support all Nader’s policies – he is not a socialist! But his candidature attracted support and interest from youth and a layer of workers looking for a way to break the two-party system of ‘Pepsi Cola versus Coca Cola’ i.e. the capitalist Republicans against the capitalist Democrats. Nader won 3 million votes running for President in 2000, the highest vote for an independent left-wing candidate in over 50 years.

Here again we see that anarchism lacks a unified position. Many US anarchists violated their abstentionist principles and voted for Nader in 2004. This was justified by ‘exceptional’ circumstances – i.e. the war in Iraq, which Nader opposed. But this was done not by adopting an agreed collective position, as the marxists did, but on a purely individualised basis. In the face of big historical tests, therefore, such as war and revolution, anarchism ceases to be a coherent or recognisable political force and dissolves into individualism. The most proletarian elements come to a position close to marxism, while other strands of anarchist opinion can lean towards liberalism. This, after all, was what happened during the Russian Revolution, when a big layer of anarchist militants came over to Bolshevism and the Third International.

9. The role of the party

But how to stop workers’ representatives from ‘selling out’ and becoming the same as all the other politicians? Anarchists point to the degeneracy of the social democratic and communist leaders and say, ‘look, we were right!’ The problem is the anarchists only address one side of the problem. Yes, there is an undeniable pressure from bourgeois society upon workers’ representatives to break from their class roots. But boycotting elections does not solve the problem. Lenin commented how infantile it was to believe as the anarchists do, that while the working class can affect a root-and-branch transformation of society it is incapable of controlling its representatives in a bourgeois parliament.

The same bourgeois pressures apply to every mass organisation, be it a party, trade union, women’s or youth movement. The experience of Spain, the only country where anarchism became a truly mass force, shows that even the anarchists are not immune from the same pressures. In the 1930s, the Spanish anarchist leaders accepted ministerial posts in two bourgeois governments – with catastrophic results for the working class.

For marxists, there can be no socialism without a mass revolutionary movement – the involvement of millions. It is impossible, as the anarchists’ dream, to inoculate a revolutionary movement in advance against the pressures, conflicting demands, and periods of ebb and flow that are an inevitable part of mass struggle. This is why we stand for the building of a revolutionary party based on a clear programme, that can deal with these pressures, analyse the situation at each new stage and put forward the necessary slogans and tactics to take the mass struggle forward. The call for workers’ representatives to live on a workers’ wage is central in this regard. This applies to workers’ organisations under capitalist rule as well as a future workers’ state. These are the means to fight the emergence of bureaucracy and bourgeois influence within the workers’ movement. There are no ready-made formulas – only active interaction and control by a politically conscious working class membership can prevent bureaucratism.

This is also why marxists insist that our public representatives are accountable to the party, under its discipline and democratic control (something anarchists reject as an infringement of the sacred rights of the ‘individual’). The Bolsheviks insisted on a representative of the leading party body within the parliamentary Duma fraction. This central representative read and if necessary amended the speeches and articles of the parliamentary deputies and had a veto over their decisions. This proved absolutely necessary, for example, during the imperialist war of 1914-18, when some Bolshevik deputies wavered under the pressure of bourgeois patriotism. This is an example of Bolshevik centralism. But in contrast to Stalinism, which ruled by bureaucratic centralism, the centralism of Lenin’s time was scrupulously democratic with countless debates and a leadership that was fully accountable to the party membership.

10. Lessons of Spain

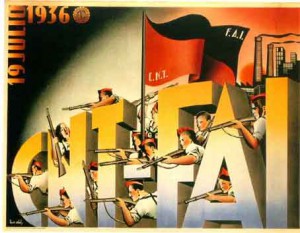

During the Spanish revolution of 1931-37 anarchism was a mass force, an experience that is unique anywhere in the world. Some of the most heroic and revolutionary layers of the working class were drawn to the banner of the anarcho-syndicalist CNT-FAI, which according even to the anarchist author Daniel Guérin, was stronger than the official government in Spain:

“In Barcelona especially, there was nothing to prevent the workers’ committees from seizing de jure power which they were already exercising de facto. But they did not do so. For decades, Spanish anarchism had been warning the people against the deceptions of ‘politics’ and emphasising the primacy of the ‘economic’… On the brink of the Revolution, the anarchists argued something like this: let the politicians do what they will; we, the ‘apolitical’, will lay hands on the economy.” [Anarchism, Daniel Guérin, Monthly Review Press, 1970]

In May 1937 the revolution hung in the balance as the workers of Barcelona, the Spanish equivalent of Petrograd or Shanghai, rose up against the attempts of the Stalinist-led police, acting on behalf of the bourgeoisie, to disarm them and roll back the elements of workers’ control that existed. The Stalinists were initially defeated by a mighty uprising of the workers. The tragedy of Barcelona and the Spanish revolution was that the working class could have easily taken power, but their leaders – in this case the CNT-FAI – came out against this on the grounds that anarchism is ’opposed to all power’.

As Guérin explains in Barcelona, “the workers were disarmed by the forces of order under Stalinist command. In the name of united action against the fascists the anarchists forbade the workers to retaliate.” [ibid.]

The anarchist leaders ended up accepting portfolios in two governments: first in Catalonia and then in the national government. Trotsky, whose writings on Spain are among his most important works, explained:

”The Anarchists had no independent position of any kind in the Spanish revolution. All they did was waver between Bolshevism and Menshevism. More precisely, the Anarchist workers instinctively yearned to enter the Bolshevik road (July 19, 1936, and May days of 1937) while their leaders, on the contrary, with all their might drove the masses into the camp of the Popular Front, i.e. of the bourgeois regime.

”The Anarchists revealed a fatal lack of understanding of the laws of the revolution and its tasks by seeking to limit themselves to their own trade unions, that is, to organisations permeated with the routine of peaceful times, and by ignoring what went on outside the framework of the trade unions, among the masses, among the political parties, and in the government apparatus. Had the Anarchists been revolutionists, they would first of all have called for the creation of soviets, which unite the representatives of all the toilers of city and country, including the most oppressed strata, who never joined the trade unions. The revolutionary workers would have naturally occupied the dominant position in these soviets. The Stalinists would have remained an insignificant minority. The proletariat would have convinced itself of its own invincible strength. The apparatus of the bourgeois state would have hung suspended in the air. One strong blow would have sufficed to pulverize this apparatus.” [Leon Trotsky, The Lessons of Spain: The Last Warning, 1937].

11. Conclusions

The shift to the right and disintegration of the old workers’ parties in the 1990s, as outlined above, led to enormous confusion within the working class, and to a certain extent blunted its consciousness especially over the issue of socialism and an alternative to the capitalist market system. A certain revival of anarchist sentiment among a layer, in particular anarchistic prejudices against the idea of a revolutionary party, are one feature of this broader process.

We marxists are confident that in the huge class battles that are inevitable in China and internationally, the working class will regain its political ’balance’ and build powerful socialist trade unions and parties. This is not an argument for waiting on the sidelines for all the process to mature. The CWI stands for struggle now on a range of important issues that we ourselves do not determine, but that emerge from the deepening crisis of capitalism. Whether the issue is combating racism, the re-emergence of slavery and trafficking, women’s oppression, war, or environmental destruction, the programme and methods of revolutionary marxism provide the only sure way forward.

Anarchism had its chance in Spain in the 1930s but failed the test of history. Revolutionary marxism is a more onerous road. It requires painstaking organisation, serious study and collective discipline – but the experience of the international working class over 150 years shows it is the only road for the liberation of humanity.