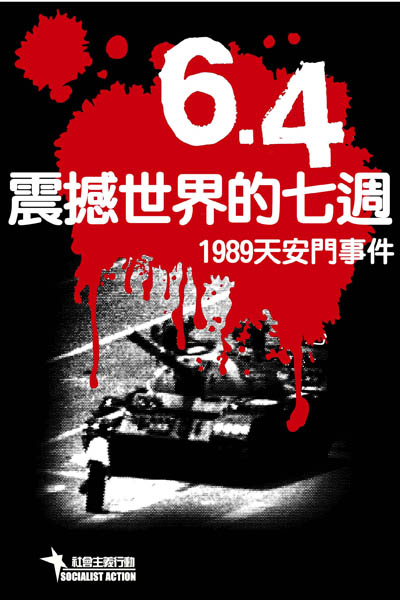

New foreword to the traditional Chinese edition of ‘Tiananmen 1989 – Seven Weeks That Shook The World’

Dikang, Socialist Action (CWI Hong Kong)

This book about the bloody Beijing massacre of June 4, 1989, was first published in simplified Chinese* in 2009 on the occasion of the 20th anniversary. It was banned by the Chinese authorities within a matter of weeks, but still distributed illegally to thousands. Now, the supporters of the Committee for a Workers’ International (CWI) in Hong Kong and China, organised in Socialist Action, have brought out this traditional Chinese** edition to introduce this material more widely to people in Hong Kong and the overseas Chinese community.

[*/** Note to English readers: Traditional Chinese writing is used in Hong Kong, Taiwan and many overseas Chinese communities, while in mainland China simplified Chinese writing is used]

No matter how hard the misnamed ‘communist’ party-state tries, the ‘spectre’ of June 4 refuses to be banished. Despite the world’s most sophisticated police controls on cyberspace and a total media clampdown on reporting these events, a new generation is probing to seek the truth. The regime has also attempted to bury the memory of 1989 underneath a heap of outwardly impressive GDP figures, a world record construction boom, and the message of China’s inexorable rise.

Crackdown – Fear of Arabian ‘flu’

Now the second largest economy, having overtaken Japan, and boasting the world’s biggest car market, biggest housing market, biggest telecoms market, most internet users (479 million), many would argue that the Chinese regime should be unfazed by the approach of yet another June 4 anniversary. But this is clearly not the case. China is in the midst of a ferocious clampdown on dissent, most clearly shown by the brutal extra-legal kidnapping of artist Ai Weiwei along with some of China’s most high profile public interest lawyers. This display of state thuggery is taking place in broad daylight, with only minimal protests from ‘democratic’ governments who long ago placed business with the Chinese dictatorship before wishy-washy talk about ‘human rights’.

The ‘disappearance’ and intermittent release of human rights lawyers – who have reappeared miraculously without their ability to speak – is another form of systematic terror against a profession that the regime wants to subdue and control. Similar selective terror is directed against campaigning journalists and bloggers. In this sense, China has ‘developed’ since the wholesale butchery of June 1989. A more sophisticated but no less sinister police state has emerged, armed with the latest hi-tech gadgetry often developed by US and other ‘democratic’ capitalist countries, who are bound by a thick web of economic interests to the Chinese regime.

The crackdown of 2011, described as “chilling” by Amnesty International, is the most severe since the events of 1989 and their immediate aftermath. Yet far from a sign of strength, this underlines the insecurity of the dictatorship. The rising curve of repression, which began at the time of the 2008 Olympics and unrest in Tibet, has become even more pronounced this year as the regime fears the ‘Arabian flu’ – protests seeking to emulate the revolutions in the Arab world. The revolutionary shocks that have swept at least 15 countries in North Africa and the Middle East, toppling two dictators and threatening many others, have exercised enormous influence on world politics. Mass protest movements in Spain and the US state of Wisconsin have been heavily influenced by the mass struggles especially in Egypt and Tunisia.

China’s turn coming?

The Chinese regime is not so blinded by hubris and its apparent economic successes that it cannot see the warning signs. Egypt also recorded several years of strong GDP growth, around 7 percent annually, under the hated US-backed dictator Hosni Mubarak. This did not endear Mubarak’s military-police regime to the Egyptian people. The country’s GDP growth has been ‘kidnapped’ by a small capitalist elite along with top military and government officials – who formally control almost half the economy. The vast majority of Egyptians are still mired in poverty, fighting for economic survival against corruption, inflation and an acute lack of jobs for young people and graduates.

China’s problems are not so different and the regime knows this, no matter how much gloss it puts on its economic achievements. The wealth gap in China – a “serious threat to social stability” in the government’s own words – is more extreme than in Egypt, Tunisia and almost all other Middle Eastern states currently hit by popular uprisings. Half of China’s 1.37 billion people live in rural areas, but together they account for just 12 percent of the country’s wealth. The World Bank says that approximately 500 million Chinese live on less than US$2 per day. At the opposite end of the social scale a minority has grown fabulously rich. China consumed 27.5 percent of the world’s luxury goods last year, to a value of US$10 billion. The sales of luxury cars increased six fold in 2010.

A social explosion on similar lines to events in the Middle East, evoking comparisons to 1989, is far from a fanciful notion in this situation. The economic contradictions accumulating beneath the surface of the ‘economic miracle’ are also a portent of cataclysmic changes ahead.

A growing number of capitalist economic commentators are warning that China’s steroid-like credit-driven expansion is unsustainable. Mark Lapolla, head of strategic research at Knight Capital, who in 2007 predicted the collapse in US financial markets, says the Chinese economy bears an uncanny resemblance to the US economy in 1929, before the onset of the Great Depression. He cites several key similarities including the massive wealth gap, rapid industrialisation and displacement of labour, opaque and misleading economic and financial data, a massive build-up of leverage (debt) across the “rising” class, and bubbles in both residential real estate and fixed asset/infrastructure.

“Essentially, in its own zeal to placate its masses with rapid growth, China has created a tide of inflation that threatens it with widespread social unrest. But if it crushes speculation and clamps down on credit, it risks a deflationary collapse that would also threaten social harmony. The upshot is that China no longer controls its own destiny. The free markets do.” [Lapolla quoted in Business Spectator, May 24, 2011]

Lessons of 1989

Given the wealth of material, especially outside China, dealing with the mass democracy movement of 1989, why is this pamphlet written by socialists so important? Firstly, it includes the invaluable eyewitness account of Stephen Jolly, who was in Beijing representing the CWI in discussions with Chinese youth and workers at the culmination of this movement and during the terror of June 3-4. Secondly, because this is one of the few works on the subject that approaches the 1989 movement from the standpoint of real socialism – of anti-Stalinism/Maoism and anti-capitalism – and stresses the often understated role of the working class in these revolutionary upheavals. The observation that China stood at the door of revolution in 1989, with similarities to events in Egypt, Tunisia and across the Middle East at the present time, is also overlooked or flatly denied by many other histories of the 1989 movement.

Socialists do not deny the role of the students, with many examples of heroism and audacity, but we also highlight the insufficiency of any political movement based solely upon students – which, however, was not the case in China in 1989, although many commentators and historians wrongly present it in this way. Socialists point out that the working class, unfortunately viewed with suspicion by many of the 1989 student leaders, is the main force for revolutionary change in every modern society. This flows from the economic role of the working class and its daily experiences, which shapes its political outlook and prepares it to lead the struggle for a socialist society.

The workers of China, and especially the working class of Beijing during the crucial days of martial law in late May and early June 1989, were the unsung heroes of this movement. It is estimated that more than half a million or more of Beijing’s factory workers, school students, housewives, office workers, civil servants and other citizens mobilised night after night to form a mighty ‘human wall’, blocking the passage of tanks and armoured detachments from reaching the youth in Tiananmen Square.

During this critical final phase of the struggle, in which Deng Xiaoping’s ruthless dictatorial regime was mustering its forces to crush the mass protests, but encountering massive problems including splits and defections, power hung in the balance in China. Workers were organising their own independent unions and discussing preparations for a general strike. Sections of youth in the capital were discussing the need for arms to defend the struggle against reaction. Attempts to fraternise and win over the army to the side of the people were on-going and making headway – as shown by the fact that only a small minority of the 200,000 troops amassed in Beijing could actually be used for the seizure of Tiananmen Square.

As our pamphlet explains, and as the CWI pointed out in its analysis at the time, the tragedy of these events was the non-existence within the mass anti-Stalinist movement of a party and programme – for genuine democratic socialism – that could show a way forward.

The political limitations of the student leaders’ approach became clear during these fateful final days when it was increasingly clear that a showdown was coming. The struggle had overstepped the bounds of a ‘protest’ movement – as the student leaders envisaged – and posed a revolutionary threat to the ruling party and bureaucracy. But this revolution lacked a revolutionary programme, a party and a fully conscious leadership, and because of this it was defeated with tragic consequences.

These were not just in terms of the horrific losses – still a ‘state secret’ in China – but also in that the victorious Dengist regime was able to steamroller ahead largely unopposed with its pro-capitalist ‘reforms’ – plundering state property in order to enrich the ‘princeling’ heirs of the old Maoist-Stalinist bureaucracy and enable the new generation to convert themselves into capitalist industrial and financial magnates while still wedded to an authoritarian state. This process, still relatively incipient in the 1980s, had been one of the triggers for the 1989 movement. The ‘princelings’ of 1989 – mere amateurs compared to today’s powerful figures – were universally vilified on Beijing’s mass demonstrations.

With the movement bloodily crushed and the spectre of mass protests thereby exorcised for a long period, the process of capitalist restoration from within the bureaucratic state apparatus would resume with renewed force after a temporary interruption in 1990-91, a period in which the Beijing regime reconsolidated its internal rule and repositioned itself internationally, assimilating the lessons of the collapse of other Stalinist bureaucratically planned economies in Russia and Eastern Europe.

The Chinese regime was able to profit from the political confusion that disorientated and stymied the organisational and fighting capacity of the working class worldwide after the collapse of the Stalinist regimes, widely and incorrectly presented by capitalist propaganda as the defeat of ‘socialism’. As this pamphlet explains, these dictatorial regimes were never socialist, although they rested upon state-owned economies, rather than capitalist economies. This was a crucial difference that imbued these societies with the potential to develop in a more balanced, rapid and planned fashion than any capitalist economy, but only on the condition that bureaucratic control was overthrown and a genuine socialist system of democratic planning and management installed. Unfortunately, this did not happen and the prolongation of stultifying bureaucratic rule sapped the planned economies of all dynamism and plunged these societies into economic regression and crisis.

Hong Kong remembers

The movement of 1989 contains vital lessons for the struggle against dictatorship today. This applies to China, Hong Kong and worldwide. The annual Hong Kong vigil on June 4 has taken on a different role in recent years as its numbers have grown and been replenished by a new generation. Numbers soared for the 20th anniversary in 2009, to an estimated 200,000, and in 2010 possibly exceeded even this number. Around a third of the participants last year were youngsters born after 1989. Also, significantly, thousands of mainland Chinese took themselves over the border to join this event. One newspaper interviewed an off-duty police officer from Guangdong province in the thick of the crowd. He was not alone, he said, other colleagues had also decided to take part.

The record turnouts in recent years are of great political significance. This is despite attempts over the years by some of Hong Kong’s pan-democratic establishment to depoliticise this event and de-link discussion about 1989 from its revolutionary tradition and the need for renewed struggle. This coincides with the split since 2010 in Hong Kong’s pan-democratic movement between an open compromise wing seeking accommodation with the dictatorship, and those who rightly reject this road.

Undoubtedly one of the reasons for the massive turnout in 2010 was the events surrounding the Legco ‘de facto referendum’ and the subsequent passage of a rotten electoral reform that perpetuates Hong Kong’s British-designed system of unelected bureaucratic governance. The 500,000 anti-government votes recorded on May 16, while dismissed as a “low” result by the Tsang administration, marked the radicalisation of a younger generation who subsequently poured into Victoria Park in their tens of thousands to mark the June 4 anniversary.

Capitalism and democracy

One of the aims of this pamphlet is to debunk the myth that capitalism stands on the side of democracy in China and Hong Kong. As Vincent Kolo explains, “Today, China is a lot more capitalist, but a lot less democratic than it was in 1989.” [Chapter 2, Tiananmen and the Working Class]

This is even clearer now, as China enters a new “dark age” of state repression, than when this was written in 2009. Other events have confirmed the anti-democratic stand of imperialist capitalist countries such as the US, Britain and the states of the European Union (EU). The revolutions in Egypt, Yemen and throughout the Arab world have targeted despotic regimes that are almost all propped up, armed and protected by US diplomacy.

The Egyptian dictator Mubarak massacred over 800 protesters – his own attempt at a ‘Tiananmen’ – before his rule disintegrated in February. Yet only days before Mubarak was ousted he was defended in the most glowing terms by the former British Prime Minister Tony Blair as “immensely courageous and a force for good”. Egypt’s army, which was Mubarak’s power base and continues to plot against and menace the revolutionary masses, has received US$1.3 billion every year from Washington – the second largest recipient of US aid worldwide. Similarly, the murderous regime of Ali Abdullah Saleh in Yemen, which has killed hundreds in an attempt to crush the revolution, is a key if increasingly embarrassing ally of US imperialism.

These facts show more clearly than anything that abstract concepts such as ‘human rights’ cannot compete for the attention of capitalist leaders with such tangibles as oil, economic power and military influence. The ‘democratic’ US and authoritarian China act in a similar way when it comes to protecting their power and economic interests.

US hypocrisy

There is nothing new in this. The new book by former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, ‘On China’, has drawn criticisms for what the Sunday Times (UK) called its “chillingly cavalier” dismissal of human rights violations and the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre. Kissinger, who has built a lucrative post-political career out of arranging meetings between US corporate leaders and Chinese government officials, is merely a more honest representative of US capitalism – perhaps because he no longer seeks office.

After the massacre in 1989 the US was quick to demonstrate its desire to work with Deng and the post-massacre government. This was despite the crocodile tears shed by the first Bush administration and other Western governments over the deaths in Beijing. James Mann, in his excellent book, ‘The China Fantasy – Why Capitalism Will not Bring Democracy to China’, explains that:

“Although Bush had announced a public freeze on high-level contacts between American and Chinese officials, he secretly sent [national security advisor, Brent] Snowcroft to Beijing for talks with Deng Xiaoping in July 1989 and again five months later. After the visits were criticised, Bush explained he didn’t want to isolate China. He wanted, instead, a ‘comprehensive policy of engagement’ with China. The choice of words was surprising, because the Reagan administration had only a few years earlier used the term constructive engagement to describe its policy of dealing with South Africa’s apartheid government.”

This shows the hypocrisy of the ‘democratic’ capitalist powers and their diplomacy, whether in the Middle East or towards China. Even the EU’s arms embargo against China, imposed after the 1989 massacre, although widely circumvented in practise may soon be reviewed. The Chinese government’s massive purchases of European sovereign debt in the crisis countries of Spain, Greece, Portugal and Ireland, has increased the European capitalists’ desire to lift the embargo and boost its profitable weapons trade.

For struggle, for socialism!

Our intention in reproducing this pamphlet is to connect the new generation of left youth, workers and democracy activists with the real lessons of 1989. These have been obscured by official censorship, but also by ‘moderate’ pan democrats who dismiss or ignore the role of the working class, and reject the characterisation of 1989 as a revolutionary struggle. By so doing, regardless of their intentions, they misrepresent these epic events.

In these pages we attempt to draw out the main lessons, not just as history, but as a guide to the coming social and political fireworks in China and worldwide. On its first publication, in 2009, thousands of copies of ‘Seven Weeks that Shook the World’ were distributed electronically – and illegally – inside China. We received many positive comments from mainland readers. One short message contained great encouragement: “I was a hunger striker in Tiananmen Square in 1989. Today I am 40 years old. I support you!”

Tiananmen 1989: Seven Weeks That Shook the World, published 2009 is banned in China. The book is available in English and Chinese editions from [email protected] price 40 RMB, US$8.00.