For a mass struggle of workers and poor to defeat imperialism and fundamentalist reaction

Leila Messaoudi, Gauche Révolutionnaire (CWI in France)

The sudden decision for a direct French military intervention in Northern Mali has not come from nowhere. Preparations for this have been underway for a number of weeks. French President, Francois Hollande, and Foreign Minister, Laurent Fabius, had announced they intended to intervene soon in one form or another in Mali supposedly “to help the Malian president to counter the offensive of the Islamists” who took control of two thirds of the Northern part of the country. The predictable collapse of the Malian army and state has accelerated things.

On 11 January, France launched the ‘Serval operation’ and the first fighting took place, with the first dead. Already, the military staff has announced an intervention that will “take the time it takes”, weeks or even more. Former Prime Minister, Dominique Villepin, speaks of a possible “stalemate”. This is because this French intervention, under the pretext of the fight against terrorism, has other motives and presents other challenges, similar to the “wars against terrorism” waged in Afghanistan and Iraq, which still continue 10 years after they began.

What is happening in the Sahel and Mali?

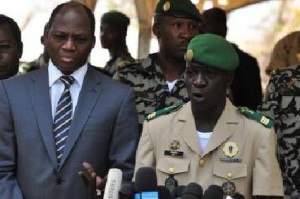

The victorious offensive by insurgent forces in the winter of 2012 (based on a precarious deal between elements of the separatist Tuareg organisation MNLA –National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad- with Islamist and Jihadist fighters of ‘Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb’, AQMI, and of ‘Ansar Dine’, an Islamist split from the MNLA) led quickly to a split in the Malian State. A coup, organised by a military officer, Captain Sanogo, deposed the President, officially for incompetence in the fight against the insurgents. Even if the coup of 21 March did not receive direct support from France, the introduction of a new constitutional process (and therefore the eviction by force of the government and president) by the body at the head of the coup (CNRDRE), accepted by the Community of the States of West Africa (ECOWAS), was supported by France, from the first days of April, two weeks after the coup.

But this coup was not enough, by itself, to restore sufficient order in the country to fight the insurgents. On the contrary, it encouraged the latter to make further advances, despite their strong internal divisions. The imperialists, particularly the French state, thus gradually made the choice to engage more strongly in favour of the Malian Provisional Government. Sanogo gradually became the new ‘strong man’ of the regime. Neighbouring or close countries have also gradually brought support to the regime, and they will now bring it concrete military support, fearing that instability will quickly spread beyond the borders of Mali.

Aftermath of colonization and crisis of capitalism = a country in decomposition

If Mali is in such a state of disarray, it is not by chance. As a country emerging from French colonization, Mali has artificial aspects (its borders having been partially drawn arbitrarily by the colonizers), and its central state has kept it together due to the repression of various social movements and movements of cultural minorities.

But what has definitely ruined the country is the different policies at the service of imperialism. In exchange for foreign investment, the IMF pushed Mali to adopt, in 1997-98, neo-liberal policies. In the name of the ‘Structural Adjustment Plan’, Mali was ordered to privatise public services, orientate the agricultural economy towards the export of cotton at the expense of other crops, and in 1994, the Malian currency, the CFA franc, was devalued by 50%. Hidden behind the official figures of economic growth, a decay of the country and of its economy followed, an economy now export-oriented, at the expense of domestic development. Remote areas of the Niger River valley experienced the most severe declines. Cotton prices collapsed in 2005, leading producers to ruin. Today, cotton is sold at a loss by peasants.

Disintegration of the state, and economic collapse: here is the picture of the actual situation in Mali, despite the country having been portrayed by imperialism as an exemplary democracy in West Africa for two decades. This situation explains the inability of the Malian government to maintain itself without outside backing, as well as its lack of support among the population. Indeed, this period was accompanied by a corrupt regime, that of Amadou Toumani Touré, himself an architect of a previous coup, and denounced for years for his corruption and nepotism.

A new possible devaluation of the CFA franc, as is discussed within the IMF, would have very aggravating consequences, turning the economy even more towards exports and preventing any import of vital products for the population.

French interests in the Sahel

Sahel countries are historically territories dominated by the former French colonial power, which has largely created these States for its own interests. Senegal, Mauritania, Mali, Algeria, Burkina Faso and Chad are among the countries of the Sahel region, between the Sahara and the savannahs of Africa. All are pretty much former French colonies.

This region is, in many respects, strategic for France. Of course the intervention is first aimed at maintaining its influence in the region, but also at protecting French interests there. The French company, Areva, has for example an uranium extraction mine in Mali. French employees of Areva are currently held as hostages in the region. Since yesterday 16 January, new Western hostages have been held by a Jihadist group in Southern Algeria, as a “retaliation against the French intervention in Mali”. Many of them have been presumably killed following an assault by the Algerian army. This last example shows how this war is not going to bring security for French or Western expatriates or workers living in those areas, quite the contrary in fact.

The development of Islamist groups and militias in the region directly threatens the strategic interests of French capitalism, especially as the Sahel is one of the few areas in which the terrain has not yet been fully explored and exploited: this is a lucrative prospect. Mali is the third biggest African gold exporter (behind Ghana and South Africa), and some see it as a future first, entering the top 10 worldwide.

Furthermore, an inter-imperialist rivalry lies in the background, and has pushed France to undertake the intervention to preserve a leading role in its ‘playground’.

France’s Malian policy

The shift in the power dynamics flowing from the so-called ‘Arab Spring’ helped to precipitate the Malian crisis, already brewing up for years. The fall of Qaddafi in Libya initially helped to rekindle the Tuareg rebellion, as thousands of Tuareg fighters who had served Qaddafi’s regime – they made up an important part of his army – fled South West towards remote Saharan areas in South Algeria, Niger and Mali, bringing with them a lot of weapons.

When it became independent the Malian State integrated, through force, a number of different national and ethnic peoples who continue to be oppressed, in particular those who were not originally from the Niger River valley, among them the Tuaregs.

France had bet on the Tuaregs in the neighbouring Niger to stem the rise of the Islamists of AQMI. But a new secessionist rebellion by the MNLA against the Malian State in January 2012, added to a tactical and temporary agreement between part of Tuaregs’ leaders and AQMI, has changed the balance of forces. This is especially the case now that in Northern Mali, the weak and secular MNLA has been virtually sidelined and chased out by Islamist factions.

Tuareg people have been marginalised and oppressed for decades, often treated as second-class citizens, and facing catastrophic living conditions. Gauche Revolutionnaire and the CWI defend equal rights for Tuareg people, including crucially their right to self-determination. We stand against discrimination of any minority and against the divide-and-rule policies which have been applied for a long time by imperialism and by the local ruling classes in the region.

However, by allying themselves with ultra-reactionary forces and supporters of an Islamist dictatorship , how can the MNLA still even pretend to defend the democratic and legitimate rights of the Tuaregs?

As far as Ansar Dine and AQMI are concerned, they are not homogeneous, and what they did, especially in Timbuktu (massacres, requisitioning of houses etc..), show that they are not liberators, as some may have expected. In reality, these forces are just occupying a vacuum. They rose up with those permanent mercenaries – jihadists and others – who were notably released by the explosion of the situation in Libya. These are the same Islamists as those in Benghazi: those people who helped to sabotage the Libyan revolution in the making, with the assistance of the imperialist powers. According to Human Rights Watch, they have started to form troops of child soldiers with the goal of leading a holy war against the small “French Satan”.

So, for the French army, leaving the quagmire of Afghanistan for the Sahel seems risky. It is about using the military firepower of France for economic and geopolitical interests, as previous Presidents have done. France, by doing nothing, might have been gradually sidelined by the USA which had started intelligence missions and military training in the region. This is why Hollande has decided to do the job himself, even if it is by engaging in a war and supporting a corrupt power.

A former minister of the dictator Traoré in power

The current Malian government does not shine for its democratic character. Hollande and Fabius are engaging in a ground military offensive, through support for the army of Diango Sissoko, the current president of Mali. The latter came to power on 11 December 2012. In a country in disarray, where military putschists and mediocre politicians all portray themselves as “rectifiers” of democracy, the choice of Diango Sissoko was made. Yet he was a faithful follower of the authoritarian regime of Moussa Traoré, which fell in March 1991 following a revolt. Diango Sissoko was Secretary General of the Presidency with the rank of minister. But he managed to gradually find his feet and regain influence in the state apparatus, and in 2002 he found himself in the cabinet of the very person who ousted Traoré.

In the absence of other solution, they opt for more of the same, hoping to find a brief period of calm. This is somehow the choice of France and the reason for the current military intervention. If the Malian State explodes, it would leave a political vacuum in the central Sahara and in the Sahel. France has a vested interest in ensuring a strong power in Mali, even an authoritarian one, if it is not to see French interests being threatened, and uncontrolled Islamist groups getting access to the capital, Bamako.

Is it justified to intervene militarily in the region?

On the international plane, the French intervention in Northern Mali is welcomed by the other countries. In France, almost all political parties support the position of Hollande. Jean-Luc Mélenchon of the Front de Gauche and Noel Mamère (Greens) might denounce the non-consultation of the National Assembly, but do not clearly oppose the war.

Images of people from Bamako gladly welcoming the French intervention suggest that this intervention is ’just’ from a human and moral point of view. It is supposedly carried out to prevent Islamist groups from ransacking, burning and killing, and imposing reactionary laws justified by Sharia law. Everything happens as if it was a ‘just war’, the militias prevailing through elements of terror and plunder. About 150,000 people have fled to neighbouring countries, while over 230,000 are reported to have been internally displaced.

Three cities in the North of Mali are now controlled by the AQMI, and in surrounding villages, Islamist militants settle down and get married and some services have been reinstated. Here, the Malian state was virtually non-existent, and some militias are playing the role of a state and are partially organizing society. We cannot say that local inhabitants are in favour of the Islamists, but they can hardly be described as in favour of the current Malian State, which has abandoned them for decades.

Moreover, the Malian army does not stand by integrity and democratic methods, being itself responsible for numerous atrocities and abuses, as has been extensively reported by Amnesty International (which cites arbitrary arrests, killings, bombings and tortures against Tuareg people, “apparently only based on ethnic grounds”). Also, many legitimately fear that the imperialist-backed offensive is likely to be accompanied by further violent retaliations against Tuareg people, and to fuel ethnic tensions.

Inequality and poverty provide the ground for the rise of reactionary forces. A real alternative to these forces will not come from the French government, which proposes to reinstate the same corrupt people as before, or others who will turn out the same way. The fact that Foreign Minister, Laurent Fabius, declared he was confident that “Gulf Arab states would help the Mali campaign”, says a lot about the supposedly ‘democratic’ intentions of the French government in this war.

It is a safe bet to say that the French military intervention will increase tensions. It is likely to be a drawn-out military campaign whose costs will also be put on the shoulders of the French working class at a time of rising austerity and economic crisis. The “fight against terrorism” is also used to justify an increased presence of police and military on the streets of French cities.

The French government will also certainly aquire, on the back of the Malian people that it pretends to protect and liberate, a few “advantages” (concessions on resources or land etc) at the detriment of Mali’s development.

France’s entering into war has triggered a state of emergency throughout Mali. It is impossible for Malians opposed to the war and to AQMI to publish their views in the press, and censorship is reinstalled. Only a resolute struggle for the rights of all, in the North as in the South, for a decent life and for the control by the population of the country’s resources in order to satisfy the needs of all , would reduce the influence of, and ultimately stop, the Islamists.

We demand:

•Withdrawal of the French troops and of the ECOWAS – against imperialism. It is not bombs and airplanes that the Malian people need, but economic cooperation and development that is not done according to the interests of French multinationals and others.

•The wealth of Mali belongs to the Malian people! For the nationalization of the land and of the commanding heights of the economy, and the financing of a real economic development plan based on the needs of, and democratically controlled by, the Malian masses

•No to the state of emergency, for the reinstatement of all democratic freedoms in Mali

•Self-determination for the peoples of the Sahel and the Sahara, as well as of the peoples within each country, on the basis of equality of rights

The only solution would be for the Malian people to come together in the neighbourhoods and in the workplaces and organize themselves, to formulate their demands and to set up armed multi-ethnic defense committees, in order to oppose any dictatorship (whether the one to be put in place with the help of France, or the one that the Islamists want to establish).

The Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions have shown the way – that only through mass struggle by working people and the poor can change be achieved.