The massive social struggles around the civil war bring up important issues that are played out in the continuing battles today to end racial, class, sexual and gender exploitation under U.S. and global capitalism.

Patrick Ayers and Eljeer Hawkins, Socialist Alternative (CWI supporters in the US)

The theatrical release of Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln is situated between important events and anniversaries. This past September 22 marked the 150th anniversary of the preliminary draft of the Emancipation Proclamation, November 6 saw the re-election of the first black president, Barack Obama, to a second term and January 1, 2013 is the 150th anniversary of the final implementation of the Emancipation Proclamation. Lincoln issued the final Emancipation Proclamation as a war measure. It declared “all persons held as slaves” within the rebel states “are, and henceforward shall be free.”

The Making of Lincoln

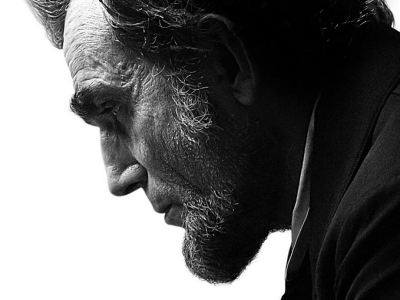

Lincoln is based in part on Doris Kearns Goodwin’s award winning biography of Lincoln, Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Lincoln adapted for the screen by award winning playwright Tony Kushner. Lincoln is directed by Spielberg and stars Oscar winners Daniel Day-Lewis and Sally Field. It has already garnered a number of Golden Globe nominations and will certainly get Oscar nominations.

Lincoln focuses on efforts to pass the Thirteenth Amendment toward the end of the Civil War. After winning reelection in 1864, Lincoln took the opportunity in the final days of the outgoing “lame duck” session of Congress to pass the amendment. Passage was not guaranteed, even though the Republicans had a strong majority. Lincoln had to deal with opposition in his Cabinet, his party, and also win support from some Democrats (who had been the main party of the slave owners). The film clearly intends to highlight Lincoln’s skills as a political leader in a period of crisis. The film also attempts to humanize Abraham Lincoln who suffered from bouts of depression not dealt with fully in the film. Lincoln’s propensity to tell stories and parables to enforce his point to soldiers and cabinet members is in full display.

Some of the most touching and powerful scenes are with his wife Mary Todd Lincoln portrayed by Sally Field and the profound grief of the passing of their son Willie at the age of 11. These also include moments of play with Lincoln’s younger son Tad and his strained relationship with his son Robert Todd Lincoln, who wanted to enlist into the union army despite Mary Todd’s disapproval. Robert Todd will join the union army in the final weeks of the war.

Great leaders

Daniel Day-Lewis is absolutely mesmerizing; epitomizing his methodical approach to acting. Lewis becomes Lincoln in body, spirit and mind. Through the sentimental and grandiose imagery in Spielberg’s directing Lincoln almost appears as a god-like figure. Undoubtedly, the choice by the filmmakers to make a film about Lincoln’s character in the limited context of the battle for the Thirteenth Amendment is meant to amplify Lincoln’s role in events.

At one point in the film Lincoln asks a soldier in the White House, “Are we fitted to the times we are born into?” And the soldier answers, “I don’t know about myself – you maybe.” The problem here for those that wish to fully appreciate Lincoln’s role in history, is that the filmmaker’s choice of events don’t help paint the full portrait of the “times” that Lincoln had to “fit into”.

By almost entirely featuring debates in the halls of power in Washington, the film is not able to explore the role of the masses in the historical process. Without the slaves, small farmers, workers, and others who were radicalized by events leading up to the 1861 outbreak of war – and even more so after – Lincoln would not have had a platform from which to lead. To fully understand the qualities of Lincoln’s leadership, it is vital to place his role in the context of the broader historical process. This could have been done in a few minutes at the beginning of the film. But, the choice by the filmmakers of Lincoln to provide a narrow focus, without providing a full historical context, serves to render history as being made by great people ordained by a power greater then themselves.

The Second American Revolution

“The struggle has broken out because the two systems can no longer live peaceably side by side on the North American continent. It can only be ended by the victory of one system (chattel slavery) or the other (free labor).” – Karl Marx

The Civil War ended in a revolutionary war against the slave-owning planters, who had dominated U.S. politics for decades before the war. By abolishing slavery, the material basis of their economic and political power was rooted out. This revolution was necessary because the first American Revolution – the war for Independence from Britain – ended in a compromise between the capitalist ruling class in the North, and the slave-owning planters in the South.

Many at that time thought slavery was a dying institution. But, with the invention of the cotton gin, and the development of the industrial revolution, demand for cotton lead to a rapid growth of slavery – and in a far more brutal form than before capitalism. This strengthened the slave-owning planters and they dominated politics in the U.S. until 1860 through their two party system – the Democrats and the Whigs.

Due to the destructive effect of cotton plantations on the soil, planters were constantly in search of new land. This brought them into collision with the rapidly growing population of small farmers in the North who wanted new lands for small “free soil” farms, not large slave plantations. In 1854, small farmers and slave-owners fought a war in Kansas over whether the new state would be a slave state.

With the rapid growth of capitalism in the North, which had its own political agenda, the two systems – the chattel slave system and the free labor capitalist system – increasingly came into conflict. The refusal of the slave-owning planters to relinquish their power made a revolution absolutely necessary.

The industrialists were in a position to lead a historic movement against the slave owners, but they had to mobilize the masses to do it. The Republican Party was launched in 1854 out of a growing democratic movement against the “slave power.” Along with the small farmers and industrialists, the new party brought together abolitionists and workers organizations that recognized an opportunity to build a powerful movement to crush the “slave power” and open the way for a radical transformation of society. The Republican program had a limited goal of stopping the spread of slave lands, but this was enough to herald a death sentence for the slave system.

Added to this opposition in the North, the slave owners constantly lived in fear of slave rebellions. With the growth of slavery to over 4 million human beings working in bondage, this fear became even greater. The slave-owners were completely dependent upon racist ideology and a state apparatus that ruthlessly enforced its needs, including enforcing fugitive slave laws and repressing abolitionist agitation. Anti-democratic measures against abolitionists spread fears in the North that the “slave power” was a threat to democratic freedoms.

In 1859, John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry raised alarm bells, not just because it raised the specter of a slave rebellion, but also because John Brown, who had fought in Kansas against the slave owners, was celebrated by many Radical Republicans in the North. When Lincoln was elected president in 1860, the slave-owners had already decided that their only hope for defending their interests was an armed uprising against the North and secession.

This was the broad historical process leading up to Lincoln’s election and the outbreak of war. On the basis of two antagonistic systems, conflict and war were inevitable.

To his credit, Lincoln fulfilled a historical necessary role in the struggle against the class of slave-owning planters. There was a historic need for the abolition of slavery and revolution. Lincoln’s determination to abolish slavery before the end of the civil war was essential for the subsequent development of capitalism over the coming decades. This also led to the development of a powerful working class, the only class in history capable of establishing a society truly based on equality. For these reasons, Karl Marx and his American allies supported Lincoln and the Union army during the war. They argued against the idea that abolition would lead to greater competition between workers and instead argued how the working class would be strengthened by the freeing of black labor from bondage. “Labor in the white skin can never free itself as long as labor in the black skin is branded,” wrote Marx in Capital.

A People’s History and Hollywood

Lincoln wasn’t an abolitionist and did not set out to abolish slavery. He also held racist views. Lincoln earlier supported colonization projects for a segment of free ex-slaves given the option to migrate to Africa and the Caribbean. Lincoln was contradictory and cautious. Lincoln would state on September 18, 1858, during the first Lincoln and Stephan Douglas debate, “I will say then that I am not, nor ever have been in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races, that I am not nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of Negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people . . . . I as much as any man am in favor of the superior position assigned to the white race.”-Abraham Lincoln, First Lincoln-Douglas Debate, Ottawa, Illinois, Sept. 18, 1858, in The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln vol.3, pp. 145-146,

But, Lincoln was a supporter of “free labor” which was crucial for mobilizing the northern small farmers, tradesmen and workers, who volunteered to fight in droves. It also drew the ire of the Democratic Party, the main political prop of slavery, who whipped up racist opposition to the “Black Republicans,” as they were called by the Democrats.

Lincoln was a talented orator who could connect with an audience from poor farmers to lawyers. We get a glimpse of this at the beginning of Spielberg’s film, when Lincoln discusses with two soldiers, one black and one white. Both of them seem inspired, reciting Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address by memory.

Lincoln’s thinking and actions were pushed by the intensifying social conflict pressure from below which was decisive in forcing him to adopt new bold proposals. Slaves themselves put pressure on the Union leaders to abolish slavery as a war measure, as they increasingly fled to northern lines in the course of the war. Termed ‘contrabands of war’ fleeing slaves were seen as striking an important blow to the economic power of the South. Abolitionist sentiments also grew enormously after the outbreak of war, thanks to the agitation of the abolitionists.

The Army represented some of the most radicalized sections of the northern workers and small farmers. It resembled nothing like the U.S. Army today, which is built through a poverty draft. The Civil War was a political war, and the Union Army was politicized. Although there was conscription, there were also thousands of willing volunteers, because they believed that crushing the “slave power” was important to the struggle for a better society. Members of labor unions, socialists and other radicals played an important role in joining and forming militias to become part of the union army. Union soldiers overwhelmingly voted for Lincoln in the 1864 election.

Slaves Struggle for Their Own Emancipation

In the opening scene of Lincoln, a black soldier raises issues about the racist treatment of black soldiers. But, it is merely a token reference to the racial tensions between the white Union leaders and the black soldiers. The movie Glory, released in 1989 and starring Matthew Broderick and Denzel Washington, explores much more the dynamic tension between Union leaders fighting to preserve the Union and further their careers, and black soldiers fighting for social liberation. The struggle by the slaves for their own social liberation was a decisive driving force of events that propelled Lincoln to ultimately abolish slavery.

Unfortunately, the black characters in Lincoln are used as set pieces lacking any real development, dialogue or influence on events. It’s greatly troubling that there’s no mention or portrayal of important African American leaders like the abolitionist freedom fighter Frederick Douglass or the conductor of the Underground Railroad Harriet Tubman who joined the Union forces. Lincoln in the last year of his life sought Douglass’s thoughts on the question of slavery, post-civil war and black enfranchisement.

In the film Mary Todd Lincoln’s confidant and seamstress Elizabeth Keckley is portrayed by actress Gloria Reuben. Keckley, a former slave herself, headed up the Contraband Relief Association made up of slaves who escaped the confederacy. The Contraband Relief Association and black abolitionists impressed upon Lincoln to give up on the colonization project, inviting contraband members to the White House and pressuring union army officials to critically examine slavery.

The film also gives the false impression that the Thirteenth Amendment came from Lincoln when in fact the Radical Republicans and abolitionist movement introduced the amendment in January 1864. The Radical Republicans were years ahead of Lincoln by advocating ending slavery with full universal equality among the races and political, economic and social enfranchisement as the radical reconstruction period (1868-1877) illustrates.

Radical Republicans like Thaddeus Stevens are portrayed as compromisers in the film, because they lowered emphasis on their broader demand for equality for blacks, thus preventing the Democrats creating a distraction from the central goal of passing the Emancipation Proclamation. But the compromises they made were important to the material destruction of slavery. This sort of compromise advances the struggle of the oppressed. It has nothing in common with the compromises made before 1860 that helped maintain slavery.

The film Lincoln allows us to re-examine the 16th president of the United States in a critical manner. It provides a background for further exploring the horrendous conditions African-Americans and working people faced following the end of the subsequent period of radical reconstruction, and the speedy rise of the U.S. as an imperial capitalist nation. The massive social struggles around the civil war bring up important issues that are played out in the continuing battles today to end racial, class, sexual and gender exploitation under U.S. and global capitalism. 150 years after abolition of slavery, the working class and poor are still the true agents of revolutionary change on the stage of world history.