Pending case against former security czar Zhou Yongkang risks dangerous splits in CCP

Editorial from Socialist《社会主义者》magazine (issue 26)

As Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign gathers momentum it is clear the power struggle within China’s ruling elite is entering a danger zone. Anti-corruption campaigns are a requisite feature of regime successions in China and they are in the first instance political – a means to settle power struggles – rather than criminal processes. At the same time Xi and the current Communist Party (CCP) leadership feel enormous pressure to show they ‘mean business’ as entrenched corruption eats away at the regime’s social base.

Speaking at the first meeting of the newly established national security commission; Xi described the current conjuncture as “the most complex time in history” for the CCP regime. The dictatorship faces a multitude of threats ranging from a dramatic economic slowdown and painful credit squeeze (deleveraging) to an upsurge in workers’ strikes and other mass protests. This background explains why Xi’s campaign has been on a bigger scale than the anti-corruption purges of his predecessors Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, and may be set to escalate further. But this risks triggering a major crisis within the regime. As Chen Yun the late CCP patriarch said, “Fight corruption too little and destroy the country; fight it too much and destroy the Party.”

Foreign media reports widely expect an official announcement to be made soon over the fate of Zhou Yongkang, the former security czar, who has been under house arrest since late last year. If Zhou is brought to trial this would be unprecedented for such a senior retired CCP leader – he was a member of the elite Politburo Standing Committee. Citing unnamed Chinese officials, Reuters (March 30) reported, “More than 300 of Zhou’s relatives, political allies, protégés and staff have also been taken into custody or questioned in the past four months.”

These are part of a vast patronage network drawn from Zhou’s former power bases in the oil industry, the Sichuan provincial government, and the state security apparatus. Such patronage networks, around senior officials and their families, have proliferated within the CPP as it has embraced capitalist restoration since the 1990s. Those detained include Jiang Jiemen, former chairman of the biggest oil company China National Petroleum Corporation (ranked 5th in the Fortune 500 list of the world’s biggest companies) and vice-minister of public security Li Dongsheng. More than ten relatives of Zhou have been placed in detention including his wife, brother, son and daughter-in-law. A staggering 90 billion yuan (US$14.5 billion) has been seized by investigators in the course of this crackdown.

Zhou was “arguably the most powerful man in China,” according to the Financial Times, which described him as a Chinese combination of former US Vice President Dick Cheney and FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover, given Zhou’s de facto control of China’s oil industry and the internal security forces. Under Zhou’s stewardship the budget for internal security (courts, prisons, investigators and police) almost doubled between 2008 and 2012 – overtaking military spending and matching Vietnam’s GDP. This fact shows the CCP regime fears internal threats to its rule over external ones. This year, the internal security budget is being kept secret, so sensitive is the issue.

The purge of his acolytes in the so-called “oil faction” began almost immediately after Zhou retired from the Politburo Standing Committee in November 2012, which is also when Xi took over the leadership of the CCP and the state. Zhou was the main supporter in the old leadership of princeling [i.e. hereditary] leader Bo Xilai, now serving a life sentence for corruption. Compared to Zhou, Bo “look[s] like a petty thief,” argues Professor Minxin Pei. Pei predicts the Zhou case will be “the ugliest and most sensational scandal involving a senior party leader that the country has ever seen.” This begs the question can Xi and the CCP leadership afford such a spectacle? Or can they control this process enough to limit the damage? As we explained in Socialist magazine (issue 24): “So grotesque are the crimes mentioned that the CCP leadership faces a huge dilemma in pursuing its case against Zhou, which threatens to drag the entire regime deeper into the swamp of political scandal.”

Zhou is not just suspected of corruption but of a litany of crimes including murder and collusion with criminal gangs. There is speculation he conspired with Bo Xilai against Xi, which some theorise is the main reason Xi is now pursuing Zhou. In so doing Xi is waiving an unwritten rule that gives retired members of the Standing Committee immunity from criminal prosecution. The long delay in announcing a formal case against Zhou, however, is a measure of the potential dangers involved for Xi – that a sharpening of elite-level struggles could trigger a wider political crisis.

“If Mr Xi is indeed declaring war on the country’s elites in the name of cleansing the party of corruption, the consequences could be grave in terms of political stability,” noted the Wall Street Journal (22 April, 2014).

One-third of officials are corrupt

Massive corruption runs throughout the CCP-state as officials and their offspring leverage their positions to amass wealth and acquire ownership of key economic assets. An unpublished internal party survey conducted in 2013 found that more than 30 percent of party, government and military officials were involved in corruption. While many Chinese would dispute these findings as too low, this report gives an indication of the scale of official corruption. The purges enacted by Xi have barely scratched the surface of this problem. Nor is this accidental, as Xi’s aim has always been a limited and targeted campaign. “The government would be paralysed if Xi went after all the corrupt officials,” an unnamed source close to the CCP leadership told Reuters.

Xi has warned on many occasions that corruption threatens the survival of the CCP-state. His campaign to bring down “tigers and flies” (senior and low-level officials) has so far resulted in more than 20 minister-level officials being placed under investigation, with half of these connected to Zhou and the “oil faction”.

In addition, Xi’s campaign against extravagance and official pomp has curbed some excesses and crimped the market for luxury brands and top-end liquor, which are commonly used as bribes. These restrictions have wiped up to 1.5 percent (US$135 billion) from China’s gross domestic product (GDP) according to one international survey. A crackdown started in February against the sex industry in China’s “Sin City” Dongguan – where prostitution is said to account for 10 to 12 percent of the city’s GDP – has led to hundreds of arrests, including corrupt police officers. This crackdown has polarised opinions with many objecting to the persecution and harassment of sex workers, while wealthy sex buyers have generally not been targeted. Others have dismissed the Dongguan crackdown as a farce saying most hotels and nightclubs that front the sex trade were forewarned by police.

Why Zhou Yongkang?

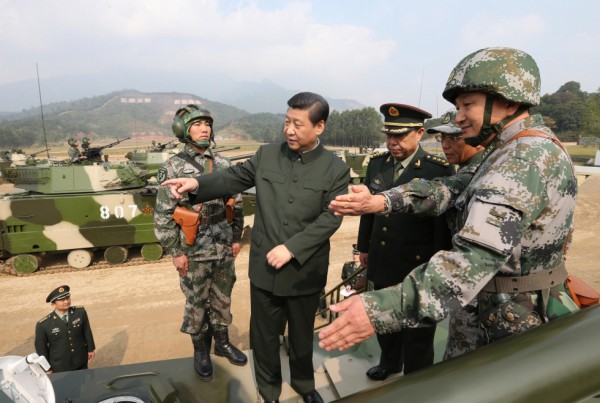

Xi’s anti-corruption campaign hopes to realise several goals at the same time: to consolidate his own position while also engineering a recentralisation of power within the regime, by imposing more control over increasingly go-it-alone local governments and state-owned industries. The extension of this purge into the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) is designed to consolidate Xi’s hold over that most important pillar of CCP rule. Deng Xiaoping famously used the 1979 war with Vietnam, which the PLA bungled, to purge the military of Mao loyalists thus eliminating resistance to Deng and his pro-capitalist “reforms”. Xi has ordered the arrest of generals Xu Caihou and Gu Junshan, the latter for trading in military promotions. Gu is accused of selling hundreds of promotions as well as profiting from the sale of military land. “If a senior colonel (not in line for promotion) wanted to become a major general, he had to pay up to 30 million yuan (US$4.8 million),” a source close to the military told Reuters. Investigators seized four truckloads of loot from Gu’s homes including a “pure gold” statue of Mao Zedong!

By moving against the previously untouchable Zhou Yongkang, Xi establishes himself as a ‘strong leader’ and sends a warning to other potential opponents, including regional governments and the party’s many patronage networks. In this way Xi is attempting to shift direction and wean the middle and lower levels of government away from today’s unsustainable debt-driven growth model. Not only does this model offer rich pickings for corruption, but more importantly it threatens to drive China towards a financial meltdown.

There are reports that Xi plans to promote 200 “progressive officials” from Zhejiang province, his former power base and a bastion of private capitalism, to dominant positions throughout the state and military in order to advance his economic reform agenda. “The anti-corruption [drive] is a means to an end,” a CCP insider told Reuters. “The goal is to promote his own men and like-minded officials to key positions to push through reforms.”

Wealth of “red elite”

The dragnet that has closed around Zhou’s family and cronies gives a glimpse of the astronomical wealth amassed by China’s “red elite”. Prosecutors and anti-corruption officials have frozen bank accounts with deposits totalling 37 billion yuan (US$5.9 billion) and seized bonds and stocks as well as jewellery and gold bullion with a combined value of 51 billion yuan (US$8.2 billion).

“There is much that we still don’t know about these assets – how many of them are held by businesses, for instance, and which are tied directly to the Zhou family – but it’s worth pausing on the fact that a group of Chinese civil servants and their associates seem to have accrued a nest egg that is somewhat larger than the gross national product of Albania,” commented The New Yorker (2 April 2014).

An in-depth report by the New York Times (19 April 2014) gives details of the wealth of Zhou’s immediate family. Typifying the way offspring of senior CCP officials have profited from official patronage, Zhou’s 41-year-old son made millions of dollars selling equipment to state-owned oil fields and thousands of filling stations across the country. The Times’ report found that three of Zhou’s relatives hold or have controlled stakes in at least 37 companies involved in the energy sector, real estate and other areas. The Zhou family’s documented wealth was at least one billion yuan, or US$160 million. As the New York Times noted: “These assets make Mr Zhou the third member of the nine-man Politburo Standing Committee that ruled China from 2007 to 2012 to have family members with documented wealth exceeding [US]$150 million.”

In other words – based on “documented wealth” – at least one-third of the members of the former Standing Committee of the CCP were yuan billionaires (1 billion yuan = US$160 million). In addition to Zhou, the others were Wen Jiabao and of course Xi Jinping himself. This leaves unanswered how much “undocumented wealth” was in the hands of the party’s top leaders and their families.

The private riches of the CCP’s top leaders make the wealth of Britain’s “millionaire cabinet” look puny. Zhou’s family wealth is ten times greater than that of Lord Strathclyde, ranked wealthiest in the British government with a fortune of US$16 million. Xi Jinping’s reported family wealth of US$370 million is 23 times his lordship’s.

Out of control?

The mind-blowing riches of the CCP elite also tell us why Xi is under mounting pressure to ‘taper’ his anti-corruption crusade. There is growing alarm within the CCP elite over who may be the next target and the risk of massive internal conflict. Last month, the 87-year-old former president Jiang Zemin urged Xi to rein in the campaign. The Financial Times quoted Jiang saying, “the footprint of this anti-corruption campaign cannot get too big.” The report said former president Hu Jintao had expressed similar reservations. In both cases, the fears expressed by Jiang and Hu reflect concerns that the anti-corruption campaign can destabilise the regime, where a system of mutually assured destruction acts to contain the struggle between rival factions and business clans.

“Anti-corruption campaigns in China have a way of getting out of control. Xi has to decide when to call off the dogs, after he feels he’s fully consolidated power,” said Ed Chow of the Center on Strategic and International Studies in Washington.

For Xi this is easier said than done, however. The anti-corruption drive can develop a logic of its own, forcing the leadership to open up new fronts – under pressure to defuse growing public anger against corruption or to win the upper hand in a power struggle. The recent arrest of China Resources chief Song Lin possibly opens just such a front, with speculation focusing on another former Standing Committee member, He Guoqiang, who is suspected of protecting Song. China Resources, which controls 2,400 companies and employs half a million people, is accused of losing billions of yuan in fraudulent coal mining deals in Shanxi province. Song’s girlfriend, a Hong Kong-based investment banker, is accused of laundering money for him and amassing a private fortune worth more than one billion yuan.

The delay in making any formal announcement over Zhou’s case has led to speculation he may escape prosecution, perhaps to be kept under house arrest indefinitely – as happened to former party chief Zhao Ziyang – because of the political sensitivity of a trial. Could Xi be satisfied, having broken up Zhou’s power base, to let the matter rest? More likely is that the process has been protracted by the need to prepare a purely economic case against Zhou, allowing the state to cover up more politically explosive issues including possible coup plots and murder. If Zhou were to be spared now this would undermine the credibility of the anti-corruption drive and Xi’s leadership.

Deng Yu-Wen, the former deputy editor of Study Times, delivered this verdict: “If you can’t deal with Zhou Yongkang, how can you speak of anti-corruption? You’ve been touting anti-corruption in front of the whole world, and yet now you suddenly stop? Doesn’t that show you can’t do it? It means you have no power. Since you have no power, how can you reform? It’s all in vain.”

Bolstering one-party rule

In April four more members of New Citizens’ Movement went on trial charged with “gathering a crowd to disturb public order.” They received jail terms of up to three-and-a-half years. Together with their leader Xu Zhiyong, who was sentenced in January to four years in jail, a total of ten members of this loose-knit civic rights group are now in prison for campaigning for the public disclosure of officials’ assets. The persecution of these activists – who stand for limited within-the-system reforms – shows how Xi Jinping is moving to fortify the CCP’s political monopoly even while relaxing the state’s economic controls.

As US-based Human Rights Watch note in their 2014 World Report: “While Xi Jinping has spoken a lot about tackling corruption and there have been some high profile arrests, the government has harshly retaliated against those who exposed high-level corruption in the government and Party.”

Under Xi the government has beefed up media censorship, internet controls, and waged a crackdown against workers’ representatives, rights activists and bloggers. Instructions to schools last year listed “Seven Don’t Mentions” (qi bu jiang) which ban teachers from airing topics such as democracy, human rights, and significantly also “crony capitalism.”

The CCP leaders are conscious of a deepening social and economic crisis. Xi believes that by increasing the state’s repressive capabilities and recentralising power he can save the CCP regime and his own position. In his critique of Stalin’s dictatorship in the 1930s, the great Marxist and revolutionary Leon Trotsky showed the flaws in such thinking:

“But history will destroy the police illusion, this time too. When a social or political regime reaches irreconcilable contradictions with the demands of the development of the country, repressions can certainly prolong its existence for a certain time, but in the long run the apparatus of repression itself will begin to break, grow dull, crumble. Stalin’s police apparatus is entering just this stage. The fates of Yagoda and Yeshov [purged chiefs of Stalin’s secret police] foretell the coming fate not only of Beria [state security minister], but also of the common boss of all three.” (Towards a balance sheet of the purges, Leon Trotsky, June 10, 1939)

This helps us to understand the real significance of the purge of former security czar Zhou Yongkang.