Under Xi Jinping’s rule repression, censorship, and ‘Big Brother’ surveillance have reached new levels, resembling and in some aspects surpassing Orwell’s science fiction nightmare

chinaworker.info statement

(3rd in our three-part series of articles on October’s 19th CCP Congress)

This process has been helped by advanced cyber-technology, often developed and sold by Western ‘democracies’. China is investing massive sums in the development of advanced technologies for economic but also political purposes – to upgrade its repressive capabilities. It has more than half the world’s video surveillance cameras, 176 million out of 245 million globally, and is leading the way in face and voice recognition technology.

Google boss Eric Smidt also recently warned that China is on course in the coming decade to overtake the US in Artificial Intelligence, which Time magazine called “the space race of the 21st century”. The Chinese regime has made no secret of its plans to incorporate AI capabilities into its ‘stability maintenance’ programmes.

China has thus become the model for ‘digital authoritarianism’ around the world, emulated by countless other autocratic regimes including Russia, Iran and Ethiopia. More and more governments are copying China in the manipulation of the internet and social media for political purposes.

“The effects of these rapidly spreading techniques on democracy and civic activism are potentially devastating,” warned the Freedom on the Net project in a recent study of 65 countries.

The Philippines government now reportedly employs a 10,000-strong “keyboard army” to drown out online opposition to president Duterte’s policies. But this is nothing compared to the 10 million paid agents in China’s “50 cent party” who earn their living by bombarding social media with pro-regime ‘news’ and comments.

Winnie the Pooh, seriously?

Despite this, the hypersensitivity of the CCP (so-called ‘Communist Party’) regime is reflected in the blocking of Winnie the Pooh on the internet after netizens pointed out the cartoon bear’s uncanny resemblance to Xi Jinping. The popularity among youth of the nickname ‘Xitler’ for the president is another sign of incipient revolt against the dictatorship.

Xi’s crackdown on dissent has been widely criticised as the most serious since the crushing of the 1989 democracy movement. In recent years as China’s economic muscle has expanded so has its readiness to project police power overseas, through the abduction of regime critics in foreign jurisdictions and the use of financial coercion to silence unfavourable publicity and political debate.

In the latest of a series of similar cases an Australian publishing company under pressure from Beijing has cancelled publication of a book, ‘Silent Invasion’, by university professor Clive Hamilton, which purportedly documents Chinese state interference in Australian politics.

However, while the capitalist establishment ingratiates itself with the Chinese regime’s authoritarian ‘habits’, these methods are beginning to provoke a growing backlash from the masses around the world. This is the orientation of the international campaign against repression in Hong Kong and China initiated by Socialist Action (CWI in Hong Kong), which places its confidence in working people internationally rather than governments and elites.

“The perfect police state”

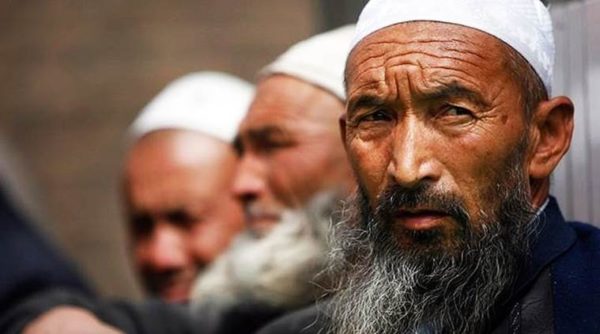

The worst repression practised by the CCP regime is reserved for Muslim-majority Xinjiang which resembles “the perfect police state” according to the Guardian. Xinjiang’s capital Urumqi (population 3.5 million) now boasts 949 police stations compared to 180 police stations in London (population 8.7 million) and 76 in New York (population 8.5 million).

Most recently, the provincial CCP authorities have begun mass arrests of around 500 ethnic Kazakhs, who now join the largest Muslim minority, Uighurs, as the focus of state repression. The brutality of the crackdown is preparing an explosive backlash but also erects new obstacles to Beijing’s economic expansion plans into Central Asia and other Muslim states.

Two recent examples underline the realities of China’s combination of unlimited hi-tech state security budget and hypersensitive regime. Shandong resident Wang Jiangfeng was given two years in prison earlier this year for using the nickname “Steamed Bun” for Xi Jinping, which refers to a televised meet-the-people visit the Chinese leader made to a working class Beijing food vendor.

Apart from the brutality of this sentence, the striking thing about Wang’s “crime” is that his remarks were made only to friends in a private WeChat group – they were not posted in public.

The riddle of Guo Wengui

More recently, a farmer in Henan province was jailed for wearing a tee-shirt with the cryptic slogan “all of this is only the beginning”. The slogan is a favourite phrase of exiled billionaire blogger Guo Wengui, who has gained notoriety and tens of millions of social media followers this year with a campaign of sensational but cryptic corruption allegations against the top leadership of the CCP.

Guo has probably acted as a proxy for CCP factions seeking to undermine Xi’s position in the run up to the 19th Congress. Alternatively, his twitter-war may just be desperate publicity-seeking in a bid to avoid deportation from the US. But the mass following his social media outbursts have assembled is a measure of the discontent building up against the regime.

Beijing’s ferocious counter campaign, which includes litigation in the US courts, measures against Guo’s relatives and associates, and more recently enlisting the support of Interpol and even of Facebook (which shut down Guo’s account) has for millions of people posed the question why is Xi’s regime so desperate to silence him?

While his motives and the veracity of his facts are far from established, Guo’s central accusation, of a ‘kleptocracy’ running China and looting billions, isn’t so outlandish. New reports have emerged within the past few days of vast fortunes invested in Hong Kong property by the families of top CCP officials including Xi Jinping’s daughter. This is of course nothing new.