150 years since the 1867 Reform Act

A divided minority Tory government was forced to make big electoral concessions to a radicalised working class 150 years ago. This created the potential for the trade unions to establish a mass workers’ party – 30 years before the Labour Party was formed. JIM HORTON looks at this significant time, drawing some lessons for today.

In 1867 the challenge that divided the Tories was not Europe but electoral reform. The key issues were extending the franchise and revising constituency boundaries to reflect big population shifts. Just months after parliament had voted down the previous Liberal administration’s mild reform proposals, it passed Benjamin Disraeli’s Reform Act which nearly doubled the electorate from approximately 1.4 million voters to over 2.5 million. An amendment granting women the vote on the same terms as men was rejected but almost one in three adult men could now vote, compared to one in five previously.

Disraeli, the Tory chancellor, was no fan of extending the franchise. “We do not live – and I trust it will never be the fate of this country to live – under a democracy”, he told parliament, giving the lie to the myth of the ‘traditional British values’ of freedom and democracy! Universal suffrage was widely viewed in parliament as a threat to private ownership of land and industry, and the wealth and profits of the aristocracy and capitalists.

The ruling class today still fears the potential danger parliamentary democracy poses to its system. For over a century it has relied on the assistance of the leaders of the labour movement to keep the working class in check. Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership victory two years ago threatened to upset this cosy arrangement and provoked a concerted effort by the whole political establishment to remove him.

In 1867 the ruling class still believed it could avoid conceding too much democracy. Both the Tories and the Liberals were united in striving to prevent a radical reform of the franchise giving the mass of workers the vote, but were divided on whether granting some or no reform was the best means to secure this. Initially, Disraeli presented a limited reform bill – aiming, partly, to unite his own party, and to aggravate divisions within the Liberal Party. His main aim, however, was to split the reform movement and thereby stem the political resurgence of workers, the scale of which seemed to portend a return to the militant days of Chartism (see Class Struggle and the Early Chartist Movement, Socialism Today No.129, June 2009).

The previous year William Gladstone, on behalf of the Liberal government, had presented his own reform bill. The reform movement at that stage gave no hint it would develop into a mass movement but the defeat of Gladstone’s bill and the fall of the Liberal administration unexpectedly unleashed protests and demonstrations across the country. It was clear that the ruling class had totally misjudged the mood of workers and their preparedness to take to the streets to force change – in much the same way as today’s political establishment misjudged the Brexit referendum and workers’ opposition to austerity.

Chartism

Memories of the Chartist movement loomed large in the minds of MPs as they deliberated Disraeli’s reform proposals. Workers in their hundreds of thousands had actively engaged in the Chartist struggle for electoral reform which included an uprising in 1838, a general strike in 1842 and, over a ten year period, three mass petitions to parliament containing the signatures of millions of workers. However, since the demise of Chartism from its pinnacle in 1848, there had been no mass working-class political activity for nearly two decades.

The establishment had been determined not to accede to Chartism’s demands for universal suffrage, which would have resulted in a mass working-class electorate. Karl Marx once speculated that, at that time of heightened political conflict, this could have led directly to the working class taking political power. Though Marx later developed his views on this issue, this was certainly the fear of the ruling class throughout most of the 19th century, and remains the case today.

The beginning of a two-decade economic upswing from the early 1850s saw the formation of new model unions comprised mainly of skilled craft workers. The leaders of these trade unions turned their backs on the industrial and political militancy of the Chartist days, although within the workplaces bitterly fought strikes still occurred over pay and conditions. The union leaders had no interest in representing the vast mass of semi-skilled and unskilled workers, nor did they seek independent working-class political representation.

For the majority of the ruling class, the so-called Great Reform Act of 1832, itself a product of mass agitation by workers, was the final say on the matter. The middle-class leaders of the reform movement hastily accepted its limited provisions, fearing they might lose control of the workers’ revolt engulfing the country. Workers’ leaders had dubbed the act the ‘great betrayal’ as its property qualification franchise benefited middle-class industrialists while enfranchising very few workers. Moreover, the concentration of the middle-class franchise in a few urban constituencies meant the aristocracy retained a significant majority in parliament.

From 1854, confident that the working class was sufficiently politically quiescent, successive Liberal and Tory governments attempted further electoral reform to extend the vote to the middle class and a small section of ‘responsible’ skilled workers. All were voted down, but these failed attempts did not provoke any significant response from the trade union leaders or stir the mass of the working class. The Whigs and Tories* taunted reformers in parliament over the lack of any sizeable support for electoral reform. Yet even at this time the ruling class was misreading the mood. The workers were not indifferent to reform but were unenthused by the paucity of the reform proposals, particularly given the absence of a lead from the union leaders.

The workers’ struggle for a voice

Despite the lack of working-class militancy, the ruling class still trembled at the thought of extending the franchise, though not for the reasons stated by some MPs, and commonly cited by historians, that workers were uneducated or supposedly lacked moral worth. More accurate is the complaint of the Hertfordshire Tory MP in 1860 that extending the vote to “manual labour must end by giving manual labour the political power over the capital that employs it”. The Liberal MP for Edinburgh recounted a meeting he had with ‘noisy agitators’ for the ten-hours bill. They had asked him whether he would reduce the working day to eight hours. His response revealed both contempt and fear: “I told them to their face that the putting of such a question only showed the danger of giving them the franchise”.

In the years running up to 1867 there was growing establishment anxiety about the increasing influence of trade unions, notwithstanding the moderate leaders, and fear that industrial action might combine with political campaigns. During the 1860s, the Liberal leader (and former Whig) Lord Palmerston and Tory leader Lord Derby agreed to lay the reform question to rest.

The revival of the movement from the early 1860s was initially led by middle-class reformers like Radical MP John Bright, with ‘reform unions’ being formed in the North and Midlands. Many of these ‘radical’ leaders were employers implacably opposed to trade unions. Bright himself had argued against the ten-hours bill. In 1864 the National Reform Union was established, a collaboration between wealthy Manchester merchants, manufacturers, businessmen, progressive Liberal politicians and working-class radicals.

In principle, the Reform Union supported ‘manhood suffrage’, yet limited its public demand to the more restrictive ‘household suffrage’. As would become a feature of all such popular movements, the interests of workers were subordinated to those of the middle class. Radicals like Bright had no problem advocating votes for those skilled workers who supported the middle-class nostrums of self-help, individualism and laissez-faire economics but were adamantly against a wider franchise for the ‘dangerous classes’.

The trade unions set up their own reform campaign. The London Trades Council had already established the Trade Union Political Union in 1860. Moreover, the revival of working-class politics was encouraged by international events: the campaign for Italian unification in 1859, the Polish revolt of 1863, and particularly the American civil war 1861-65. All of these were viewed as popular struggles for freedom.

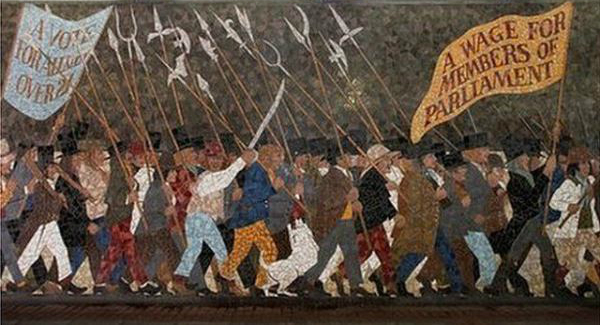

In 1865, the Working Men’s Garibaldi Committee, established to welcome the Italian unification leader to London, became the basis of a new reform organisation, the National Reform League, which was supported by former Chartists. Karl Marx’s International Workingmen’s Association played a leading role in its formation, and in the whole struggle leading up to the Second Reform Act of 1867. The Reform League had a mass following in Lancashire, the West Riding of Yorkshire, Tyneside, Birmingham and London. By the beginning of 1867 it had 400 branches, compared to the Reform Union’s 130.

The trade unions entered the political field at a time when they were also engaged in campaigns against anti-trade union laws, viewing the franchise as an important means to achieve full legal rights. The Reform League was committed to universal manhood suffrage yet from the outset its union leaders were susceptible to ideas of class collaboration and agreed to joint campaigns with the Reform Union. Both organisations then supported the very limited proposals of the Liberal government in 1866. As Marx noted, both the ends and means of the Reform League were crucially different from those of the Chartists.

Capitalism and democracy

During the general election campaign of 1865 electoral reform was not an issue. However, the death of the anti-reformer Palmerston a few months after the Liberal Party’s victory, and his replacement as prime minister by Earl Russell, placed the issue back on the agenda. A reform bill was introduced in 1866 by Gladstone, a former Tory who joined the aristocratic Whigs soon after the Tories split in 1846 over the repeal of the Corn Laws.

Gladstone attacked the very concept of democracy, making clear he had no intention to democratise the nation. His reform bill proposed extending the vote to occupiers of property in the boroughs worth £7 in rent a year, and those lodgers who rented property worth £10 a year, rents requiring wages way beyond that of factory and agricultural workers. Gladstone reasoned that giving “the vote to £6 householders… would be to transfer the balance of political power in the boroughs to the working classes”.

One of the rebel Liberal MPs, Robert Lowe, had terrified the House of Commons with the spectre of the rising power of the trade unions. He warned that workers would say: “We have the machinery; we have our trade unions, we have our leaders all ready, we have the power of combination – when we have a prize to fight for we will bring our new voting power to bear with tenfold more force than ever before”. This would lead, Lowe said, to the destruction of social hierarchy, the confiscation of the property of the rich, and the draining of wealth away from the upper classes to the lower orders.

Edward Horsman, a former Liberal cabinet minister, warned: “Democracy is upon us!” He told parliament that “there is an irreconcilable enmity between democracy and freedom” – that democratic rights for workers would undermine the freedom of the ruling classes to amass profits. Just over a century later Tory MP Ian Gilmour argued that, if parliamentary democracy were “leading to an end that is undesirable or is inconsistent with itself, then there is a theoretical case for ending it”. Gilmour was warning that having granted the franchise to the working class, workers should not be permitted to vote for the abolition of capitalism, and its replacement with democratic public ownership of the commanding heights of the economy, the only way to achieve genuine democracy.

Mass anger

Gladstone expected opposition from within his own party but with a parliamentary majority of 80 he was confident that his bill would pass. In the event, a substantial number of Whig MPs voted with the Tories to defeat the bill, which led to the resignation of the Liberal government. In response, an enormous demonstration was held in Trafalgar Square the following month. The assembled became incensed as speakers referred to the sneers and insults of MPs during parliamentary debates against workers and their ability to govern themselves. As the minority Tory administration took office, maintaining it had no intention of bringing forward further proposals for electoral reform, daily protests continued in Trafalgar Square.

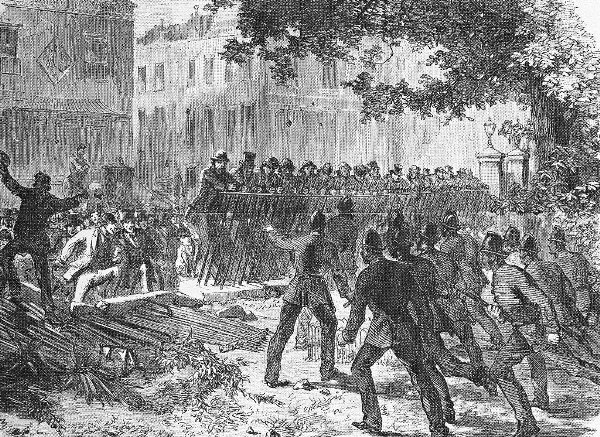

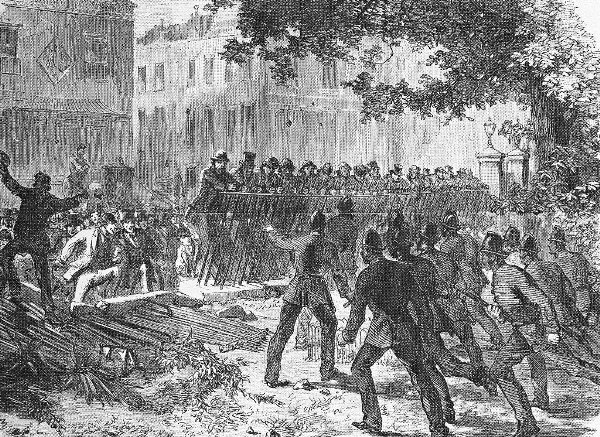

The Reform League called a rally in Hyde Park later in the month, raising the spectre of the Chartists’ 1848 demonstration on Kennington common. The trade union leaders, still seeking respectability, accepted the government ban on the gathering. Under orders from the home secretary the police used physical force to lock out the protestors but an angry 200,000-strong crowd tore down the railings. Carrying their union banners they gained access to the park. The carpenters’ banner bore the slogan: “Deal with Us on the Square. You Have Chiselled Us Long Enough”! Three nights of rioting followed and order was only restored by the intervention of the Reform League leaders.

In October and November the protests spread to other towns and cities. Three hundred thousand marched through Birmingham, a quarter of a million in Manchester, tens of thousands in Glasgow, plus thousands of smaller gatherings in almost every town and village in the country. Working-class discontent was gripping Britain. Speakers from Ireland urged formal links between the Reform League, the Fenians and the struggle for Irish independence.

In February 1867 a full delegate meeting of the Reform League warned that, unless universal suffrage was granted by parliament, “it will be necessary to consider the propriety of these classes adopting a universal cessation of labour until their political rights are conceded”. The builders’ union leader George Potter threatened a week long general strike if the vote was not granted immediately to every household and lodger.

With the situation in the country extremely tense, the government was compelled to draft its own reform bill. When Disraeli presented it to the Commons on 18 March three cabinet ministers resigned in protest. Disraeli’s original proposals were more moderate than Gladstone’s. In the boroughs there was to be household suffrage, limited by two years’ residence and personal payment of rates. This excluded half a million householders, the ‘compounders’, whose rates were included in the rent they paid to their landlords. This extension of the vote to some workers was balanced with dual votes for owners of more than one property, and a ‘fancy franchise’ for those with substantial savings or a higher education.

The ranks of the Reform League understood that politicians representing landlords and capitalists would never concede meaningful reform without mass pressure from the working class. They pushed their leaders into reaffirming their commitment to universal manhood suffrage, and into holding another demonstration in Hyde Park on 6 May. Placards went up all over the country and thousands of leaflets were distributed. The government banned it and enrolled 15,000 special constables. The police and army were put on alert. In defiance of the ban, the Reform League led a procession of up to 500,000 workers unopposed into Hyde Park behind a red flag topped by the cap of liberty, a symbol of the French revolution also used by the Chartists. The red flag was the emblem of the new socialist International Workingmen’s Association.

Ruling class retreats

This humiliation for the government forced the resignation of home secretary Horace Walpole. Disraeli was now faced with a stark choice: enfranchise the ‘respectable’ working class or face a return to the mass politics of the Chartist days at a time when socialist movements were developing in Europe. Eleven days after the Hyde Park protest Disraeli accepted an amendment to his bill from an obscure backbencher to give the workers’ movement a significant victory in the campaign for universal suffrage. The journal Punch referred to this as the ‘Hyde Park Rail-Way’ to reform.

The final bill conferred the vote on all male households in the boroughs regardless of the size or value of their home or whether they were compounders or paid rates in person. It reduced the residence requirement from two years to one. This quadrupled the number of enfranchised workers compared to Disraeli’s original proposals. The fancy franchises were dropped. Lord Cranborne accused Disraeli of being “afraid of the pot boiling over… At the first threat of battle you throw your standard in the mud”.

Yet the Tory government had been caught off guard by the size of the revolt that followed the defeat of the Liberal reform bill, particularly its resilience to attempts to suppress the agitation by force. The parliamentary debates revealed the sense of panic that was gripping the corridors of power. Disraeli had little option but to concede. Friedrich Engels recognised the significance, explaining that the Reform Act “opened out a new prospect to the working class”, enabling it “to enter into the struggle against capital with new weapons, by sending men of their own class to parliament”. In terms of independent working-class politics, however, the leaders of the Reform League lacked the consciousness of the Chartists. Lenin had described the Charter Association, formed in 1840, as the first working-class party.

In 1867 it was safer for the ruling class to extend the vote to sections of workers as the working class did not have its own political party. As a precaution, however, MPs voted against an amendment to pay legal expenses from the rates. They calculated that the extortionate costs of election campaigns would deter independent working-class candidates and the formation of a separate political party for labour, something the ruling class feared more than granting workers the vote. The Liberals and Tories then set out to win working-class support, establishing for the first time proper party structures at a local level.

Yet the act had provided an opportunity to the trade union leaders to transform the Reform League, with its huge radicalised following, into a mass party of the working class. Instead, in a vain attempt to prove their respectability, they accepted capitalist finance to fund a Reform League campaign to persuade workers to vote Liberal in the 1868 general election. After that election, the Reform League was disbanded and a period of Lib-Lab politics opened up. In effect, the union leaders collaborated with the Liberals to delay the establishment of independent working-class representation.

It would take the revival of socialist ideas after the ending of the economic upswing in the mid-1870s to pose once again the question of establishing a mass workers’ party. In particular, it was the emergence of the militant new unionism of the semi-skilled and unskilled workers 20 years after the Reform Act which would create the conditions and determination to set up the Labour Party at the dawn of the 20th century. The battle in the labour movement between class collaboration and independent working-class politics continues.

* The Whigs, dominated by an oligarchy, were the historic party of the landed aristocracy and the big bourgeoisie. They claimed to be more progressive than the Tories who mainly represented the landed squirearchy. The Whigs embraced capitalist development but strove to prevent it from undermining the established aristocratic ruling class. After 1867, the weakened Whigs merged into the right wing of the Liberal Party which robustly represented growing capitalist interests.