Hong Kong’s democracy movement, which has mobilised millions in the past 20 years, is under attack

Adam N. Lee, socialism.hk

The government is rigging elections, jailing activists and rolling out new laws to force obedience to the Chinese dictatorship. Our ‘questions and answers’ deals with the most common questions.

Is Hong Kong a democracy?

Hong Kong has never had a democratic political system. Its government is not elected. According to the Economist Intelligence Unit’s global ‘Democracy Index’, Hong Kong is ranked 71 in the world, on the same level as Paraguay and Namibia. Hong Kong’s Chief Executive is chosen once every five years by a committee (1,194 members) dominated by billionaires and millionaires. The Chinese regime controls the process – only its candidates can win. The current Chief Executive, Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor, was chosen in March 2017 with just 777 votes.

Why is the Hong Kong government banning election candidates and disqualifying elected legislators?

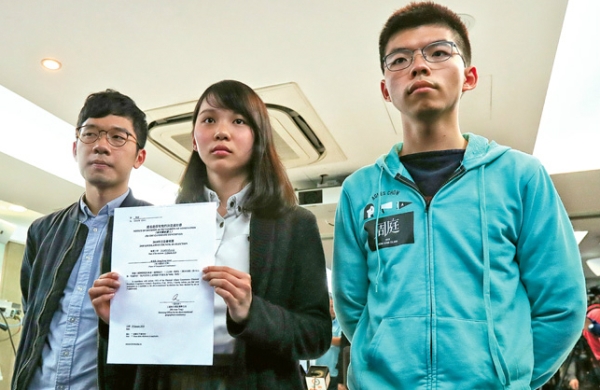

It wants to quell the democracy movement and demands for genuine elections (universal suffrage). It follows orders from the Chinese regime, which fears the democracy struggle will ‘infect’ China, endangering its hold on power. Six opposition legislators have been disqualified – referred to as ‘DQ’ – from the Legislative Council (Legco) using new rules to declare the oaths they swore were “invalid”. The government has banned more than a dozen individuals from standing in elections.

Some parties are also now banned as in the case of student-led Demosisto. Some former election candidates are banned because the courts put them in jail – on government orders. Even Hong Kong’s mini-constitution the Basic Law says everyone has a right to stand in elections, but in reality this is not the case.

Is the government acting within the law?

It is trying to hide its political agenda of increased authoritarian control behind a smokescreen of upholding the law. The government’s Justice Department ordered the court to ‘re-sentence’ young protesters in August 2017, who were initially given non-custodial sentences (community work) after being found guilty of “unlawful assembly”. All were all re-sentenced to prison terms of between six and 13 months. (some of these sentences have since been overturned by the Court of Final Appeal).

In the case of the “invalid oaths” used to throw out six legislators, this came from a completely made-up law imposed by China’s National People’s Congress (NPC). The NPC, an arm of China’s dictatorship, can make binding ‘interpretations’ of the Basic Law – so the unelected NPC is the ultimate power over the courts in Hong Kong.

Does the Basic Law protect democratic rights?

The Basic Law enshrines basic civil liberties and some democratic rights. But its commitment to universal suffrage is weak and contradictory – saying this is an “ultimate aim”. It states that the Chief Executive (and therefore the government) “will be appointed by the Central People’s Government on the basis of the results of elections or consultations” (Article 3, section 4). The Basic Law is so full of caveats it’s a gift to a despotic regime like China.

The Basic Law was never endorsed in a democratic vote. Its democratic elements were included under mass political pressure. It was imposed on Hong Kong in the 1980s after a deal was struck between the British colonial regime and the Chinese dictatorship, through an elite Basic Law committee that was dominated by the two governments and Hong Kong’s wealthiest capitalists. The Basic Law outlaws any other economic system than capitalism, until 2047, and also bans budget deficits – a key tenet of neo-liberal economics.

Was it better under British rule?

Many people today say it was better, but they generally mean there was less poverty and inequality. And from the 1970s to the 1990s, the housing crisis wasn’t as extreme as it is now. One thing it wasn’t, however, was democratic. The British were colonialists not liberators. They ruled Hong Kong for 156 years and never once held an election for government.

Nowadays the British establishment is largely silent over Hong Kong, because it is more concerned about billions of dollars worth of business deals with the Chinese regime.

Is the Legco democratic?

Only half the seats in Legco are elected. It was designed – by the British – to provide a ‘democratic’ cover for an unelected government. In Legco elections the pro-democracy opposition regularly win a big majority, roughly 60 percent of the votes, but because of its undemocratic make-up the pro-government camp win 60 percent of the seats.

Today, as part of the government’s authoritarian crackdown, the powers of the Legco have been further weakened. After expelling opposition legislators last year the pro-government side had a large enough majority to re-write the Legco rules – a self-inflicted “castration”.

If the Legco is powerless why does the government need to rig elections and ban candidates?

Despite its limited powers, the Legco has become an important platform for the struggle for democratic rights. The opposition legislators can lift the veil on government corruption, pro-billionaire policies and the new threat to democratic rights.

The moderate pro-democracy parties, which shy away from mass struggle and favour conciliation with the regime, have lost ground to more radical groups – these got a quarter of the total vote in 2016. This reflects mass radicalisation and frustration that the democracy struggle has arrived at a dead-end. So now the government is further rigging an already undemocratic system, to keep more radical forces out of the Legco. Ultimately, this will just shift the focus away from the Legco, towards the streets.

How does the government control the Legco if the opposition wins 60 percent of the popular vote?

Because the Legco is not democratic – half its seats are filled from so-called functional constituencies, controlled by big business and special interest groups. Only around 240,000 people are eligible to vote in functional constituencies out of a total electorate numbering 3.7 million, so each functional vote is worth 12.5 ordinary votes.

What are the main demands of the democracy movement?

The main demand is to end the current undemocratic system by introducing genuine universal suffrage.

But the Chinese dictatorship fears that such a seemingly modest reform in Hong Kong would set off a chain reaction. So rather than reform, the dictatorship is moving in the opposite direction. That is why it reneged on a vaguely worded promise, made in 2005 (in the face of massive political protests), to allow a phased transition to “universal suffrage”.

What was eventually offered was nothing like real universal suffrage but a manipulated Iranian-style election system. This was the infamous ‘831 ruling’ (31 August 2014), which sparked the 2014 Umbrella Revolution.

What was the Umbrella Revolution and what did it achieve?

This mass movement, with umbrellas used to protect demonstrators against police pepper spray, began on 28 September 2014, after the government used heavy force to disperse youth protests. The Umbrella Revolution did not have a developed list of demands or clear leaders. It was a largely spontaneous mass rejection of Beijing’s fake universal suffrage. Up to 2.3 million people joined the protests. Thousands occupied the streets for a total of 79 days – longer than the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989.

The government rode out the storm, harassing the protests with police and triad gang raids, court injunctions, and a media barrage saying the movement was “losing support”. Its secret weapon was exhaustion. Occupy-type movements – as seen in many countries – can be a good starting point for a mass movement for political change, but occupation alone has never won. There is a need to escalate to strikes and to build mass democratic committees to direct the struggle. Against a powerful dictatorship the democracy struggle needs to be based on the working class, which is not just society’s biggest class, but also the force that makes the economy and society run. In South Korea and South Africa mass strikes by the workers tipped the balance in the struggle against dictatorships.

How can the government’s undemocratic policies be stopped?

Only by mass resistance. The first step is to realise that there will never be a “final” attack – disqualification, jailing, undemocratic laws – these are all pieces of a long-term agenda by the Chinese dictatorship to extend its control over Hong Kong and shut down the democracy movement. Their model for Hong Kong is Singapore or Macau – with a much-weakened democratic opposition. So, the fight back cannot solely focus on court cases or elections, necessary as these are, and much less on waiting passively for the storm to pass.

Those democratic forces that are serious about resisting the authoritarian crackdown should help initiate a democratic conference open to all groups to discuss a one-day Hong Kong-wide strike as part of a strategy to relaunch mass resistance. This could begin with the students. A new democracy movement needs to be built with a working class core – a new party of grassroots workers and the poor. Most parties today have become vehicles for one or two ‘leading personalities’ mostly active on social media. But what’s needed is a democratic organisation with a mass membership of 10,000s, rooted in campaigning and struggle. Such a force could coordinate the fight back and appeal across the border to the Chinese masses to join the anti-authoritarian struggle.

Is the struggle in Hong Kong gaining international support and can that make a difference?

For decades the main pro-democracy parties paid little attention to international solidarity because they believed democracy was “only a matter of time”. This was never true: democracy has only ever triumphed as a result of mass revolutionary struggle. They also wrongly believed there was significant support for democratic change from foreign governments. But as Beijing steps up its attacks on democratic rights, this has not met with any serious protests from capitalist companies and governments. They have built strong ties with the Chinese dictatorship based on a common interest in putting money before ‘politics’.

There is enormous potential sympathy around the world for the struggle for democratic rights in Hong Kong and China, but not among ministers and CEOs. It is among the workers, youth, women and other oppressed layers. This is where the international solidarity movement against authoritarian rule needs to be built.