Is the problem neoliberalism or capitalism?

The current economic crisis may have been triggered by the coronavirus pandemic, but its roots lie in a deeper crisis of capitalism going back to the financial crash of 2008–9. This ongoing crisis lays bare the failure of capitalism in general, and the unrestricted free markets of neoliberal capitalism in particular. For the working class, this downturn points more strongly to the need for socialist change. For the ruling class, the crisis has forced them to intervene in the economy in ways which completely contradict “free market” orthodoxy. This includes measures to prop up demand — usually described as “Keynesian” — by putting money directly into the pockets of working people.

The shift towards Keynesian measures was made explicit on April 3, when the editorial board of the Financial Times, a long-standing defender of neoliberal policies, called for “radical reforms” in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic: “Governments will have to accept a more active role in the economy. They must see public services as investments rather than liabilities, and look for ways to make labour markets less insecure. Redistribution will again be on the agenda; the privileges of the elderly and wealthy in question. Policies until recently considered eccentric, such as basic income and wealth taxes, will have to be in the mix.”

The latest round of the crisis has seen a more serious turn toward state intervention than in 2008–9. In a span of weeks, government economic stimulus passed by Congress has surpassed 10% of GDP. By comparison, the 2008 bailout took several months to pass and was “only” equal to 5% of GDP. Of course the overwhelming bulk of the “stimulus” is a bailout for the banks and corporate America. As we have discussed elsewhere the crisis has revealed how corporations have gorged on debt in the wake of the bailout ten years ago. This is an example of the underlying weakness that threatens to create a financial crisis of biblical proportions. However, the coronavirus quarantine has first and foremost drastically cut consumer spending, and the capitalists who have laid off millions of workers now expect the government to make up the demand shortfall with stimulus checks and expanded unemployment benefits.

This type of measure is not just being taken in the U.S. In Britain, Boris Johnson’s Tory government has implemented a program that gives unemployed workers 80% of their income up to £25,000. The European Central Bank has removed spending limits for EU member states.

Why are capitalist governments, including those which yesterday were enforcing drastic austerity measures, suddenly giving cash to workers, and where are these measures headed? Will stimulus checks be able to halt the crisis? In order to make sense of this about-face, socialists need to understand what Keynesianism is. Though often synonymous with the New Deal of the 1930s, Keynesianism doesn’t mean social welfare but represents a worldview with a specific understanding of how the capitalist economy works.

What is Keynesianism?

Keynesianism is a bourgeois economic school of thought that views the capitalist economy as the sum of all expenditures, divided into four sectors: consumption, government spending, business investment, and net exports. An economic downturn is seen as one of those sectors refusing to spend, and the fix is seen as having another sector increase spending. To prevent crises, the government can adjust a variety of economic levers like lowering interest rates to incentivize spending, or intervene directly with fiscal spending. Keynesians would characterize the current crisis as a decline in production combined with “declines in corporate investment and autonomous consumption” and with the export sector unable to pick up the slack, government stimulus becomes the remedy.

The intention of these measures is not primarily to help working people, but to save businesses first and foremost. As Keynes said in 1931, “If our object is to remedy unemployment it is obvious that we must first of all make business more profitable.” Although the recent stimulus checks are a lifeline to workers to buy necessities and pay rent, even if they fall short, that is not their primary purpose to the ruling class. The administration issued stimulus checks so that working people can return this money to corporations through spending. But at the very same time, state governments with massive shortfalls are preparing to make massive cuts to social spending. Stimulus measures will be temporary and the ruling class will look for every way they can find to offload the costs of this crisis onto the backs of the working class.

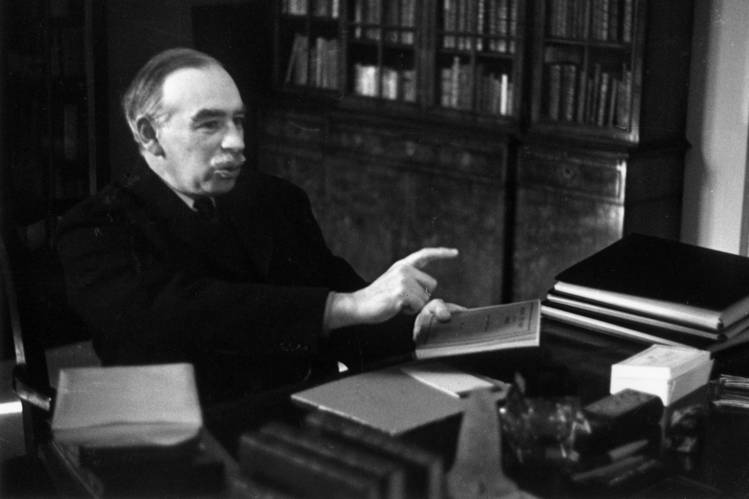

British economist John Maynard Keynes first developed his theoretical framework during the Great Depression. Given that prevailing orthodox economic theories at the time were unable to explain the crisis or point to policy solutions, the ruling class pragmatically turned to Keynesianism for a way out. Roosevelt, who campaigned in 1932 on budget cuts, was forced to reverse gear and start the New Deal in 1933 to provide much-needed employment, albeit at poverty wages, to millions of workers. Beginning in 1934, the capitalists were also confronted with a historic strike wave that led millions of industrial workers to unionize. To protect their system from the workers’ movement, the ruling class made concessions.

However the New Deal failed to deliver a sustained economic recovery and the country slipped into recession again in 1937–1938. It took state-directed war production and the massive destruction of capital in WWII to create new fields for profitable investment and allow capitalism to recover.

Structural Keynesianism

After the war, the ruling class, particularly in Western Europe and, to a lesser degree in the United States, were politically forced to adopt “structural Keynesian” policies which led to extensive social welfare systems. The returning millions of working-class soldiers, having survived the Great Depression and then fighting in the hell of World War II, made it clear to their governments that conditions could not go back to the way they were. In Europe, the capitalist political establishment, facing collapsed economies and lacking any credibility because of their collaboration with fascism, had to offer an alternative to the political threat posed by the Soviet Union.

Keynesianism also played a key role in the world economy through the Bretton Woods system, a tightly regulated international monetary order starting at the end of WWII and lasting until 1971. Essentially, all international currencies were bound to the U.S. dollar (a provision which Keynes, a co-author of Bretton Woods and an economic nationalist, fought bitterly against — he wanted to bind world trade to Britain). This was supposed to control the inflation and interest rates of member countries to help international growth, at the cost of national central banks losing some monetary autonomy.

With ready international acceptance of state intervention in the context of the need to restart collapsed economies, Keynesians could implement “industrial policy” in a number of advanced countries that incentivized development of national industry with elements of state planning. While certainly radical by today’s standards, the goal of these measures was first and foremost to help restart the profit machine. Indeed, using industrial policy, massive social spending, and international trade bodies as economic levers, Keynesians presided over the longest boom in capitalist history from the ‘50s-’70s. It appeared that Keynesianism had mastered the boom-bust cycle.

While the tweaking of economic levers had an effect, the main material factors behind the long boom were the destruction of capital in World War II, the domination of U.S. imperialism which suppressed inter-imperialist rivalry, rapid population growth, invention of productive new technologies, and bringing more women into the workforce. The capitalist class — who most of the time fight tooth and nail against paying taxes for social spending or restrictions on the use and flow of capital — could temporarily tolerate both in an age of unprecedented economic expansion.

The boom was not sustainable. In the latter years of this “Golden Age of Capitalism” productivity growth began to slow. Capitalism has an inherent tendency to “overaccumulate” (overproduce) industrial capital as it introduces more machinery into production, which adds to cost overheads and grows output faster than society can absorb, slowing down profitability. The postwar boom displayed this tendency, and the slowing boom ended in 1973 as the advanced capitalist countries came under an oil embargo from OPEC, creating a severe energy shortage and triggering a sharp recession.

Keynesian policies couldn’t overcome a material shortage by lowering interest rates. The result was growing inflation. The massive spending of the U.S. imperialist war machine in Vietnam also prompted excessive inflation, without adding anything back to the economy. This combination of stagnant growth and inflation — known as “stagflation” — severely discredited Keynesianism to the ruling class, which abandoned Bretton Woods, attacked social spending, and turned toward neoliberalism.

Despite the scale of today’s crisis, and the discrediting of the neoliberal model which has dominated for the past 40 years, this does not mean the ruling class can or will return to structural Keynesianism. The requisite social conditions, a booming global economy and tight coordination between national capitalisms, are no longer present. The Keynesianism we are seeing today is going to look more like the ad-hoc measures of the ‘30s, because we are headed into a deep slump of the world economy and a sharpening of inter-imperialist rivalry, especially between the U.S. and China. Of course, in the face of mass pressure or the threat of revolution, the ruling class could still make big concessions.

Is the problem neoliberalism or capitalism?

Since the crisis of the 1970s, the ruling class shifted its economic approach from Keynesianism to neoliberalism, a particularly parasitic form of capitalism. Neoliberalism, as an ideology, is defined by limiting the role of the state in the economy to the protection of free markets and private property. In practice, neoliberalism is characterized by the large-scale privatization of public services, the opening up of international markets to free trade, the stabilization of currencies and debts, and naked class warfare waged against the working class. It is also characterized by a growing role for financial capital and a massive expansion of credit. All of this represented a certain fix to the profitability problem but only through piling up contradictions which would inevitably explode at a certain stage.

Advocates of Keynesianism, especially on the left, portray the rise of neoliberalism as the product of either greed or ignorance. This sentiment has strengthened since 2008 as neoliberal capitalism has run into crisis. But the ruling class adopted neoliberalism in response to Keynesianism’s own crisis in the 1970s, which saw declining profitability, stagnation, inflation, and bankruptcies of businesses unable to find profitable investment.

Neoliberalism served to restore profitability, through massive amounts of speculative activity, attacking the state sector through tax cuts and privatization while massively increasing the rate of exploitation of workers through speedups, longer hours, and cutting wages. None of this addressed the declining rate of productivity growth which reasserted itself in the U.S. after 2000 and is a key underlying factor in the current crisis.

Neo-Keynesian economists, like Paul Krugman, see unregulated markets, as well as the laissez-faire system that were key features of neoliberalism, as the source of crises, rather than the capitalist system as a whole. They point to the austerity mania of the political establishment, especially in Europe, after 2008–09 as failing to bring the economy back to health.

A system in decline

Here we need to point to a key difference between Marxism and Keynesianism. Marxists see capitalism as being in a long term decline. In the 18th and 19th centuries, capitalism led to a massive and unprecedented expansion of human productivity. World War I was an expression of the impossible contradiction between the nation state and the further development of a world economy on a harmonious basis. The period between the wars saw no resolution of the underlying crises — it was marked by stagnation and society lurching between revolution and counter-revolution. The postwar boom was an exceptional phase. The productivity slowdown and profitability crisis of the ‘70s was the beginning of capitalism resuming its longer term decline as a social system.

Keynesians believe the system is not in decline and can be fixed. They view crises in terms of “underconsumption,” the driving down of workers’ wages and living standards lowers demand, preventing businesses from being able to sell their products. This process, a “crisis of realization” in Marxist terminology, is certainly a cause of crises. But it’s not the whole story.

During an economic downturn, one of the economy’s sectors refuse, or are unable, to invest in production. This leads to a decline of production and economic activity generally, resulting in job losses and a collapse of living standards for the working class. Businesses shrink or go bankrupt, and the working class faces mounting poverty and unemployment. This reality forms the basis of Keynesian theories of underconsumption, that workers are not spending enough for businesses to be profitable. If state intervention can stimulate demand, the Keynesians argue, investment will return and capitalism’s crises can be circumvented.

This is a one-sided view of capitalist crises. Keynesianism superficially views the economy as an accounting entity, where fixing a negative number in one sector simply means adding its complement in another. It cannot not answer why business periodically refuses to invest in production all at once. Marxists understand it is because the entire capitalist system is driven by dog-eat-dog competition for profit, so corporations overproduce commodities and capital resulting in glutted, saturated markets.

Even during the recent economic recovery, corporations saw less and less return on investment in expanding production. For example, corporations ploughed their profits heavily into the financial casino including stock buybacks. In the current crisis, we see overproduction in the form of Apple hoarding over $200 billion in cash in 2019, unable to find profitable investment. This again points to the longer term crisis of productivity growth and capitalism’s inability to really expand the forces of production as it did in the past, in particular during the postwar boom. If corporations refused to invest during the recent “boom” years, why would the Keynesian policy of giving them more money during bust years make them invest?

Both neoliberalism and Keynesianism developed in response to different crises faced by capitalism. And both failed to stabilize capitalism in the long term. This poses the question of what can be done to get us out of the current crisis.

Can Keynesianism solve the crisis?

Government spending can boost demand within a limited scope, and can resolve certain conjunctural aspects of the crisis of capitalism. The New Deal provided much-needed employment and relief for millions of American workers. Today, under the immediate impact of the coronavirus lockdown, certain government spending can mitigate the worst aspects of the crisis.

But this only works within limits. Again, Roosevelt’s New Deal was only sustainable in an advanced capitalist country with a strong currency like the dollar, and could not by itself pull the economy out of depression. It took the destruction of World War II and other conditions as explained to ignite the postwar boom. One obvious problem with resolving the current slump is that, unlike a war or natural disaster, it is not destroying capital in a way that would allow for such a dynamic to occur.

What we are likely to see now in the U.S. is a pragmatic and reluctant adoption of Keynesian measures alongside vicious austerity and possibly even privatizations. At the same time as the government is sending out stimulus checks, states are threatening massive cuts to social services and the Republicans clearly relish the thought of the Post Office going bust.

In the long run, Keynesianism can’t provide a solution to the crisis. Pumping trillions into the economy won’t do away with the glutted markets that discourage investment. The $2.2 trillion fiscal stimulus has temporarily calmed financial markets, but bourgeois economists have now dropped the completely unrealistic talk of a rapid v-shaped recovery.

Japan’s recent experience with three decades of Keynesian policies is a further demonstration of its inability to solve serious capitalist crises. At the start of the ‘90s the Japanese economy crashed and the government responded with public works projects, lowered interest rates, and other Keynesian measures that have lasted to this day except for a period of austerity in the early 2000s. At the cost of accumulating the highest debt-to-GDP ratio in the world, Japan’s Keynesian measures have eked out an average of 1% annual real GDP growth over the last three decades, interspersed with short recessions. Current Prime Minister Abe has been implementing his own right-wing Keynesianism called “Abenomics” which mixes deregulation and anti-labor laws with payouts to corporations. All this completely failed to restore sustained growth, and has instead shifted workers toward precarious, part-time or gig work. Deep social crisis or renewed class struggle, which Keynesian social and infrastructure spending have helped to avert, could reignite under Abe’s right-wing reforms.

Keynesianism and socialism

For socialists, the increasing adoption of Keynesian measures even by right-wing governments exposes the hypocrisy of the ruling class. When Bernie Sanders called for Medicare for All, he was met with a constant refrain from Biden and other corporate Democrats of “How are you going to pay for it?” But when the Federal Reserve wants to spend part of its recent $2.3 trillion aid package for businesses and states on stocks and junk bonds to prop up financial markets, nobody asks them how they are going to pay for it. If you can find the money to save big business, why can’t you find the money to save working people?

However, while Keynesian measures include business stimulus, they also include social welfare programs. Keynes’s ideas have increasing support on the reformist left among activists who genuinely do want to fight in the interests of the working class. Some, like Bernie Sanders, see Keynesian policies as examples of “democratic socialism” pointing to Scandinavian welfare states which have also been eroded by neoliberalism. Others recognize that Keynesian policies leave capitalism intact, but see such policies as a means of gradually achieving socialism through peaceful means. Either way, these left Keynesians see capitalism and its crises through the same lens as Keynes himself, blaming the crisis exclusively on neoliberal capitalism, rather than capitalism in general. Revolutionary Marxists see things differently.

The logic of capitalism will always lead to an overaccumulation of capital and overproduction, which in turn creates crises. It is absurd that society having too much wealth can create layoffs and poverty but the problem is that this wealth is created by the working class and appropriated by the capitalists. It is this contradiction of idle workers surrounded by the wealth they created that socialists seek to resolve through a planned economy. If big business is taken into democratic public ownership by workers under a planned economy, we can redirect the economy to produce goods for use rather than profit, thereby avoiding overproduction. If production needs to be reduced, a socialist economy freed from profit can simply retrain workers, or reduce the workweek to maintain full employment with no loss of income for workers, paid for by the tremendous wealth created by modern production that’s being hoarded in the hands of the 1%.

Keynesianism is fundamentally not socialism, but an attempt to save capitalism from itself. And even if it were possible to fully apply left-wing Keynesian policies it would maintain the capitalist system intact, albeit with more regulations, social services, and selective state ownership. This isn’t a moralistic critique of Keynesianism for “not being radical enough.” Reforms that benefit the working class also cut into the profits of big business, which means they are under constant threat of being scaled back or reversed in the interests of the capitalist struggle for profit.

When Bernie Sanders raised the need for Medicare for All in a debate, Joe Biden responded by pointing to Italy, which has single-payer health care but failed to adequately respond to the coronavirus crisis. Biden’s opposition to Medicare for All is indefensible, but the truth is that, since 2001, Italy gutted the national health system, with the aim of transforming it into a profitable appendage of private health care. We should fight for reforms like Medicare for All, but we also need to go beyond it, taking the entire healthcare industry, and ultimately all of the biggest corporations and banks that dominate the global economy, into public ownership.

While Marxists reject reformism, they don’t reject the struggle for reforms. Marxists fight for reforms as part of what Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky called the “transitional method.” This entails building a bridge between consciousness as it is today and understanding the need for socialist transformation of society. We fight for reforms that would immediately benefit the working-class, from raising the minimum wage to rent control to raising taxes on big business but we also raise demands that point beyond capitalism such as bringing the energy industry and the big banks into public ownership under democratic workers control. But we fight for these reforms through the organized mobilization of the working class; they will not be won through convincing the capitalists to adopt clever monetary tricks or policy hacks.

Moreover, we point to the limitations of any reform and the need to go farther. In our program for the coronavirus crisis we call for the following: “Hazard pay” for all essential workers; all workers to be paid full wages if they lose their job to the pandemic or the recession; a freeze on all rent and mortgage payments; an emergency plan to house the homeless; reopening closed hospitals; taking over empty buildings to establish free medical clinics; massively accelerated training and hiring of medical staff; and taking over workplaces that refuse to adhere to safety standards. Demands such as these link an immediate response to the crisis to the need to take the economy into public ownership under democratic workers’ control and management.

The only definitive solution to the crisis of capitalism is through public ownership of the top 500 corporations and democratic and rational planning of the economy. The profit motive needs to be taken out of the picture, so that the democratic decisions of workers and consumers can balance spending and income in a way that can assure that production is directed where it’s needed. Through such socialist planning we can achieve a decent standard of living for all, address climate change, and do away with the crises that face capitalism.