More than $5 trillion wiped off global stock markets in two weeks since Chinese devaluation

Vincent Kolo, chinaworker.info

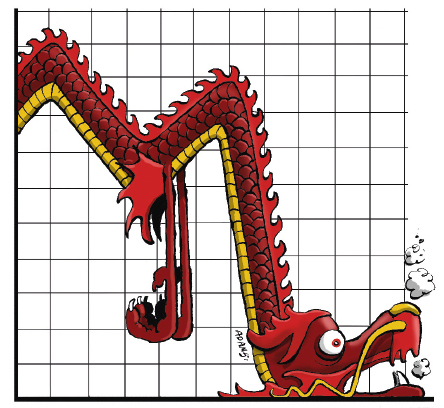

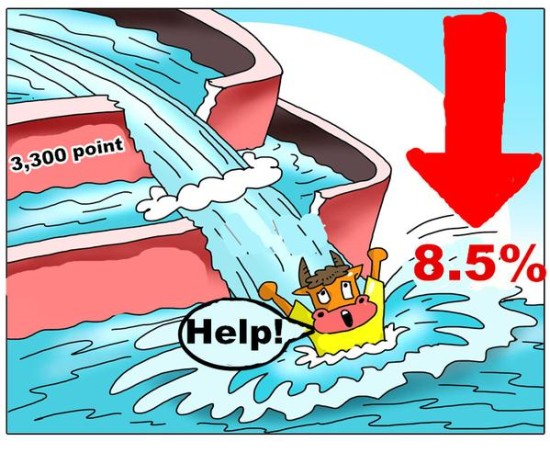

“Black Monday” exclaimed China’s official news agency Xinhua as China’s stock market slumped 8.5 percent on 24 August. This triggered the sharpest falls on world stock markets since the 2008 financial crisis on growing fears of a China-led global recession.

Previously, Wall Street was the epicentre of global financial turmoil with the US banking meltdown of 2008, but this time it is China’s economic crisis and its leaders’ visible loss of grip that has been the trigger. The shock ‘mini devaluation’ of the Chinese yuan on 11 August snapped most of the capitalist world out of its false sense of security, believing that Beijing “has a plan” to deal with the country’s accelerating slowdown. Since then over $5 trillion has been erased from the value of global stock markets. This mass destruction of wealth in the space of a few days proves beyond any doubt that capitalism is an insane and moribund economic system. “More than €400bn has been wiped off the value of Europe’s three hundred largest companies today,” reported Reuters on Black Monday as the financial rout spread to Europe.

Former US Treasury Secretary Larry Summers tweeted, “As in August 1997, 1998, 2007 and 2008 we could be in the early stage of a very serious situation.” Even US presidential candidate Donald Trump, not the brightest crayon in the box, warned the world could be heading into depression. Damian McBride, who served Britain’s former Prime Minister Gordon Brown as an economic advisor, warned that the current crisis could prove to be “20 times worse” than in 2008.

Hong Kong’s Hang Seng Index suffered its sharpest fall since 1987, and its stock market has now officially entered a ‘bear market’ having shed more than 20 percent since its April peak. Stock markets in Indonesia and Taiwan are also in ‘bear’ territory. Similarly, stock markets in developed economies suffered huge reverses on Monday compounding the panic of the previous two weeks, with London’s FTSE 100 having lost 18 percent of its value since April, and Germany’s Dax losing 20 percent over the same period. Australia’s stock market plunged 8 percent on Monday, one of the biggest falls, and a reflection of its massive exposure to China.

The global meltdown spread to commodities with oil, copper, aluminium and nickel hitting their lowest levels since the onset of the global crisis in 2008. Oil prices, which play a pivotal role in the global economy, and which have fallen from $115 per barrel in the summer of 2014, slid further to below $43 per barrel. This piles the pressure upon oil producers from Russia to Venezuela which are already in recession. The Bloomberg Commodity index which monitors prices of 22 raw materials slipped to its lowest level this century having fallen 17 percent this year and 40 percent over the past three years.

China has been the main motor of global growth in recent years, contributing around one-third of global growth compared to 17 percent from the US economy. It consumes around half the world’s metals and dominates the market for other commodities including agricultural goods. The sharp price falls for these commodities has stalled growth in many commodity-exporting countries, but is also heightening deflationary pressures throughout the world economy. While falling prices can provide a short-term boost to economies that import commodities, if this becomes entrenched as prolonged deflation it threatens to cripple economic growth and exacerbate debt problems, which are growing everywhere and not least in China itself. This is what happened in Japan, which entered a deflationary crisis in 1990 – marked by economic stagnation and increasing levels of debt – from which it has never emerged. China today displays many similar features to the Japan of the 1990s as does the global economy.

Devaluation shock

When China devalued the yuan two weeks ago, somhething it has historically been reluctant to do and indeed considered as a “nuclear option”, this shook the global capitalist system. At one stroke this confirmed suspicions that the Chinese economic malaise is much worse than Beijing has admitted or reported in its official statistics, which as we have explained are doctored and misleading. The devaluation, minimal to date, also raises the spectre of copycat devaluations (a so-called ‘currency war’) which in turn could, as Albert Edwards of the bank Société Générale put it, unleash “a tidal wave of deflation” over the world economy.

The confused way in which China’s devaluation was executed has left capitalist commentators scratching their heads in stunned disbelief. As Paul Krugman noted in the New York Times (14 August): “They appear to have been taken completely by surprise by the market’s predictable reaction… Investors began fleeing China, and policy makers abruptly pivoted from promoting currency devaluation to an all-out effort to support the yuan’s value.”

The depreciation of the currency – by 3 percent against the dollar so far – is too small to have any real impact on China’s exports. Furthermore the regime and China’s central bank, PBoC, have had to step up their currency interventions to support the yuan, or risk an even bigger flight of capital from China. An unprecedented $800 billion has left China in the past five quarters – money being routed into dollar assets and other ‘safe haven’ currencies by Chinese companies and speculators as well as foreigners.

This leaves Beijing’s devaluation, which the PBoC seems to have resisted until the last moment, looking like ‘the worst of all possible worlds’. The decision has created mayhem on global markets and set off a chain reaction of falling currencies but without delivering any real boost to China’s economy. In fact, the sharp falls in Asian and other ‘emerging market’ currencies of the past two weeks have completely cancelled out and indeed reversed any benefits to China from devaluation in terms of enhancing exports. The Malaysian and Indonesian currencies have fallen to their lowest levels since the 1998 Asian crisis, amid a general downward slide of Asian currencies (with the exception of the Japanese yen which is seen as a ‘safe haven’ currency). The Russian rouble, South African rand and Turkish lira have struck their lowest ever levels. Another – and major – effect of the devaluation will therefore most probably be to postpone the long expected increase in US interest rates planned for September by Janet Yellen and the Federal Reserve. This complicates the position of the US government and adds to the deepening tensions between Washington and Beijing.

Spectacular missteps

The Chinese regime has spectacularly mishandled its stock market meltdown, spending over $1 trillion on support measures during the past ten weeks, from which it has salvaged absolutely nothing. The selloff on “Black Monday”, the worst for eight years, puts share prices below the July 8 level when the government’s rescue operation was launched. Indeed today’s losses wipe out all the gains of the stock market – the world’s second largest – since the start of the year.

These events have marked a turning point in perceptions of the regime. The CWI and its Chinese section have long challenged the myth of ‘infallibility’ that surrounded the dictatorship and its alleged economic competence. But until very recently the Chinese leaders have been held up as ‘model technocrats’ with leading representatives of global capitalism falling over themselves to pay tribute.

A succession of botched measures during recent months – first inflating an unsustainable stock market bubble, then attempting to prop it up after it had burst, culminating in a hesitant and panicky currency devaluation – have shredded the authority of Beijing’s economic mandarins. The latest move, although unannounced, is shown by the regime’s failure to intervene with fresh market support measures as the stock index tanked on Black Monday. Beijing has evidently realised it cannot support both the stock market and the currency and chosen to focus on the latter. These measures represent a catalogue of incompetence with few parallels. They also demonstrate the limits of Beijing’s power to control economic developments which the global capitalists have overestimated.

“The real casualty over the summer is the government’s credibility. When you look at the stock market intervention, when you look at the FX [devaluation] botch as I would call it a couple of weeks ago, and then you look at the Tianjin blasts, you see a government that is most certainly not in control. You look at this and it sends a very poor picture about China’s competency at the leadership level. Who else is responsible here? [President] Xi Jinping seems invisible.”

The above comments from Fraser Howie, co-author of the book Red Capitalism, is typical of bourgeois analysts today. Many of these commentators were fans of China’s leaders until recently and are now experiencing what small children experience when they discover Father Christmas doesn’t exist.

China’s stock market crash was entirely predictable, as share prices lost any connection to the real economy. Recent economic data has confirmed the severity of China’s problems. Factory output has contracted for five months in a row and is now at a six year low. Former growth industries like smart phones and cars – China is the biggest market for both – are also contracting. Despite a recent ‘stabilisation’ of house prices, construction starts fell 16.8 percent in the first seven months of this year. In recent years, China has accounted for half of global construction, so on a yearly basis this would translate into an 8 percent fall in construction worldwide. This explains why commodity markets – from oil to soya beans – have been hammered in recent weeks. Also, some of the biggest US corporations have seen billions of dollars wiped from their share values because of their dependence on the Chinese market. This includes Apple, General Motors, and Yum Brands (KFC and Pizza Hut) who all sell more products in China than in the US. Apple – the world’s most valuable company – has seen its market capitalisation shrink by 18 percent in the past six months.

Global crisis of capitalism

Today’s financial turmoil underlines the blindness of capitalism which stumbles from one crisis to another. The CWI and its Chinese section have previously warned that the next phase of the global capitalist crisis could be “Made in China” – a perspective which is becoming increasingly likely. But the problems of the Chinese economy, and its crushing debt burden which is the origin of the desperate policy zigzags of recent months, are rooted in the historical impasse of global capitalism.

In 2008, as the global crisis threatened a worldwide slide into a 1930s-style depression, the Chinese regime launched a mega-stimulus programme based on unprecedented amounts of credit. This initially yielded stunning effects as China’s GDP accelerated and appeared to escape the gravitational pull of the global recession. Stephen King, chief economist at bank HSBC, described China as “the shock absorber for the global economy” – although today its role is reversed as a source of shocks for global capitalism. This is because the stimulus-driven growth of the post-2008 period was based on an unsustainable accumulation of debt, which quadrupled from 7 trillion in 2007 to 28 trillion today. This has reduced the regime’s ability to further stimulate its way out of crisis, as we are witnessing today. Prior to 2008, each yuan of credit generated around 0.8 yuan of GDP. But nowadays it only generates 0.2 yuan of GDP.

China’s problems are mirrored in the growth of global debt which has increased by $57 trillion since the end of 2007, to a staggering $199 trillion, according to McKinsey Global Institute. The world economy will enter its next recession in much worse shape than it entered the last one. During the shaky economic ‘recovery’ of the past few years whole sections of the capitalist economy have been dependent on financial ‘life support’ from governments and central banks, especially through massive ‘quantitative easing’ (QE) measures from which the economy has not been able to extricate itself. If interest rates remain at today’s historically low levels (near zero, or in some cases actually negative) it means the capitalists will have even fewer weapons at their disposal with which to face a new recession. At the same time, the working class has faced uninterrupted austerity since the onset of the crisis in 2008, suffering sharp falls in living standards in many countries, meaning that a new recession will detonate unprecedented political movements and challenges to capitalist rule. It is this fear that is driving the turmoil on global markets.