The only winner from tribunal’s ruling is the arms industry

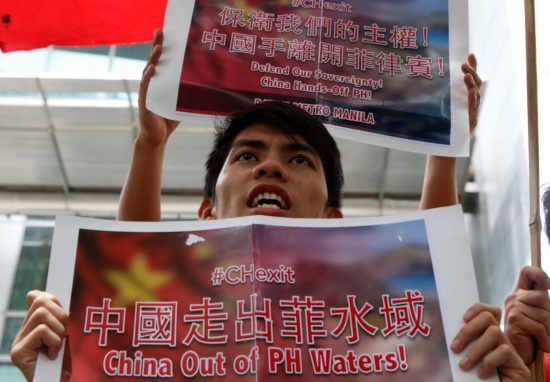

On 12 July the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA)* tribunal in The Hague delivered its verdict on the South China Sea, heavily favouring the Philippines which initiated the case. The verdict is a major diplomatic blow to China, even though the tribunal has no enforcement powers and the Chinese regime boycotted the tribunal, announcing in advance it would ignore the outcome.

The tribunal ruling, 500-pages long, covers many points but its essence is to rule that China’s territorial claim, the so-called nine-dash-line, has no legal basis and also that China has violated the Philippines’ sovereignty in the contested waters. The tribunal ruled that the treaty UNCLOS (United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea), which came into effect in the 1980s and which China has signed, supersedes any historical claims that the Chinese regime asserts over the disputed island groups and ocean areas.

The tribunal’s verdict will have major geopolitical repercussions in East Asia and on Sino-US relations in the coming period, even if the precise reactions of the various competing powers is hard to predict at this stage. Vincent Kolo, editor of chinaworker.info gave us his response.

What does the tribunal decision signify?

What it certainly doesn’t offer is any solution to the conflict. This is a conflict that has become more severe, more heavily militarised, in recent years. Potentially, it can trigger military exchanges and war in the region, even if that is not likely as an immediate prospect. This ruling is like pouring petrol on the flames. The only people who really have cause to celebrate this decision are the arms exporters and military heads who want bigger budgets.

As socialists, we have never put any faith in the United Nations and its various treaties. The UN has never solved any major crisis or armed conflict, rather the opposite. This decision is like opening a gigantic cans of worms, which can have unpredictable consequences for all the rival powers. The South China Sea is a marine version of the Balkans, with overlapping and fiercely competitive claims and the potential for one side’s actions to trigger unforeseen reactions. There are many competing sides; it’s not just about China versus the US.

What will China do now?

That is one of the things that is hardest to gauge at this stage. It’s not clear that even the tops of the Chinese dictatorship have a clear plan, because even Xi Jinping and his team may have been surprised by the severity of the ruling against them. While Beijing dismisses the ruling as meaningless, it makes China more diplomatically isolated and hands its rivals – principally the Philippines, but this decision can also embolden others – a huge diplomatic and propaganda boost. This is without doubt a PR victory for US imperialism and assists its ‘pivot’ to regain the military and economic initiative in East Asia. But this ‘victory’ could also come back to bite them.

Beijing is furious, and that’s perhaps an understatement. The tribunal’s ruling is a massive slap in the face, a humiliation, despite their position of ignoring it. This can undermine the power of Xi Jinping and inject all kinds of unforeseen factors into what is a fierce power struggle within the pinnacles of the Chinese state. Even some of Beijing’s critics will have been surprised by how overwhelming is the decision against it. Many expected it to go against China but in a more balanced or ambiguous way. But instead the decision is a demolition of Beijing’s case. One commentator says this is the sharpest international diplomatic setback for the Chinese regime since 1989, and the sanctions imposed (briefly) after the Tiananmen Square bloodbath. The Economist, which also admits the ruling will increase tensions, calls it, “the biggest setback so far to China’s challenge to American influence in East Asia”.

What effect will this have on China’s internal politics?

Xi risks being seen as a weak and indecisive leader if he does nothing. That would cancel out four years of investment in cultivating a ‘strong man’ image that is crucial to his agenda of shaking up the economy and power at the top. He has whipped up nationalism and could now become something of a prisoner of his own ‘Great China’ propaganda.

There are posts going viral on social media in China, of smashed iPhones and calls to boycott Apple products (which are made in Chinese factories!). Xi doesn’t want protests on the streets; he is more of a ‘control freak’ than his predecessors who sometimes tacitly encouraged protests (such as those against Japan in 2012) to allow the masses to let off steam. If this starts to happen in China in the coming period it is rather a sign that the regime is getting desperate and the crisis at the top is intensifying. [Small protests did occur outside KFC restaurants in around 10 cities including Hangzhou and Changsha after this article was published, but were soon stopped by the authorities. Significantly, the Communist Youth League – a party faction whose most prominent member is Premier Li Keqiang – gave some support to these protests, a sign of tensions within the regime.]

So, clearly, this ruling could have massive repercussions inside China. It puts big pressure on Xi and his allies to react. In Hong Kong, the powerful anti-government and even anti-China mood among youth can be given new impetus if the Chinese dictatorship is seen to be a ‘paper tiger’ unable to react in the South China Sea. What goes for Hong Kong applies to Tibet, Xinjiang and other regions where Beijing’s rule is deeply unpopular.

In Taiwan, under its new DPP government, the possible repercussions are even more complicated because Taiwan as the ‘Republic of China’ (ROC) has its own historical claims in the South China Sea, similar to China’s. The tribunal ruling also undermines these territorial claims and puts the new president, Tsai Ing-wen, in a quandary. If she does not respond vigorously enough she is open to attack by the Kuomintang opposition and ‘ROC nationalists’ for being pro-US/pro-Japan and not sufficiently standing up for Taiwan’s interests. Tsai has immediately come under pressure from the Kuomintang to go to Taiping Island, which Taiwan controls, to reassert Taiwan’s sovereignty claim (Taiping was downgraded from ‘island’ to ‘rock’ by the tribunal, meaning it has no basis for claiming the surrounding waters as Taiwan’s territorial waters). But Tsai also fears taking any actions that could worsen her government’s relationship with the US and Japan.

What are the regional implications?

We cannot exactly say at this stage because a lot depends on how the US handles itself, if it tries to act as an enforcer of ‘the law’ as laid down by the tribunal, by stepping up its naval missions in the contested waters for example, this would be a provocation to China. It is a very unstable and potentially explosive situation, because each side’s internal politics and crises (there is a US election of course) can influence how they project power in this conflict.

China has previously threatened that it could impose an Air Defence Identification Zone (ADIZ) over the South China Sea, which would be an escalation and could pressure a US response. It has also threatened to start construction i.e. an airstrip, port, military installations, on the Scarborough Shoal (Huangyan Island in Chinese), which is a particular ‘red line’ to the US as it would put Chinese forces just a few hundred kilometres from US bases in the Philippines. Both these options would entail a high risk of the conflict escalating.

It is also possible China, as a tactical diversion, might step up its manoeuvres in the East China Sea over territorial disputes with Japan. The right-wing nationalist Japanese leader Abe has just won another election (in the Upper House) and is looking to press ahead with his plans to let Japan’s military off its ‘pacifist’ tether. A tougher attitude against Japan could be used by Xi to conceal any softness over the South China Sea. But of course this option also contains great risks.

The Philippines government, with Duterte recently installed as new president, will ride on a nationalist wave, a certain euphoria arising from this ruling, but actually Duterte’s position is to try to strike a deal with China, or at least to cool tensions and kick-start greater economic cooperation. The case against China in the The Hague was filed by Duterte’s predecessor, Aquino, who is more clearly aligned with the US. The US doesn’t want any rapprochement between Duterte and Beijing to get too friendly and so this ruling can be used by the US and its supporters in the Filipino political establishment to throw a spanner in the works.

What we can say with certainty is that this ruling does nothing to calm the tensions, it does the exact opposite. It does not ‘clarify’ the disputes but rather injects an even greater risk of armed conflicts or skirmishes. For the masses of the region, from China to the Philippines and beyond, this is just bad news; more reasons for the nationalist politicians and warmongers to hijack public funds for military spending and to whip up militaristic sentiment to sidetrack people’s anger from the economic malaise at home.

Socialists have always explained that international capitalist institutions like the United Nations play no progressive role whatsoever. None of the corrupt ruling elites that are engaged in this conflict offer a solution; they are all the enemies of the working class and the poor. We stand for international solidarity and the urgent need to build mass working class parties throughout East Asia that fight capitalism and austerity, and stand up against nationalism and militarism.

*The PCA is an arbitration body set up in 1899 in The Hague, Netherlands, at an inter-governmental conference initiated by Russia’s Tsar Nicholas II. It claims 121 countries as member states. It is not a United Nations agency.

READ: More background on the South China Sea conflict and the socialist answer.