Shockwaves from Middle East to Korea in wake of Trump’s resort to ‘missile diplomacy’

Editorial from Socialist《社會主義者》magazine issue 42

Donald Trump’s cruise missile attack on a Syrian airbase on 6 April, during a round of “beautiful chocolate cake” with China’s Xi Jinping, marks a reckless and dangerous escalation of tensions in the Syrian conflict and wider Middle East, as well as a significant ramping up of tensions in East Asia over North Korea’s nuclear programme.

These events, accompanied by some of the most bizarre and tragicomical public statements (“Even Hitler didn’t gas his own people,” said Trump’s press spokesman Sean Spicer), underline the volatility of world relations today as well as the unpredictability of the crisis regime running the world’s number one superpower.

Trump claimed his decision to use cruise missiles was in retaliation for the Syrian regime’s use of sarin gas – a banned chemical weapon – which killed 87 people including 31 children in the rebel-controlled town of Khan Sheikhoun. Responsibility for this appalling attack is still unclear however, while the fact remains that all sides have resorted to unspeakable brutality during a nearly seven-year war that has killed 400,000 and forced half the population to flee their homes. This applies both to Syria’s hardline Assad regime backed by Russia and Iran, and the rebels backed by Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Western powers, whose core forces are right wing islamists.

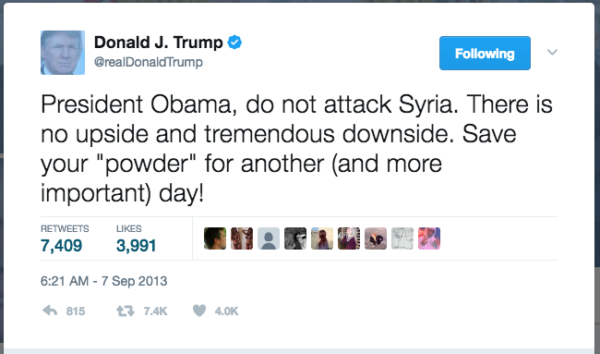

“Do not attack Syria, fix USA”

Trump’s actions mark a 180-degree turn. He previously on many occasions said the use of force against Syria would be a mistake, telling the Obama administration, “do not attack Syria, fix USA”. Previously, Trump also signalled openness towards cooperation with Russia, and even with Assad, because he believed the defeat of ISIS should be the main priority of US policy.

The unpredictable president’s military and foreign policy goals are clouded in even greater uncertainty than before. In the Guardian newspaper, Spencer Ackerman said Trump’s administration had announced “five different policies in two weeks,” on Syria, with top officials like Rex Tillerson (Secretary of State) and Jim Mattis (Defence Secretary) contradicting one another.

Trump’s claim to be defending innocent civilians and children, however, is hypocrisy. His twice-attempted Muslim ban (blocked by mass protests and the law courts) included an indefinite ban on Syrian refugees arriving in the US. Three quarters of these refugees are women and children and fully one-third are children under 12-years old.

Also, the nature of the 6 April missile strike was militarily limited, rendering it largely symbolic, to such a degree that the targeted airbase was back in action within 24 hours conducting bombing raids against the same town of Khan Sheikhoun. “The American raids did nothing for us,” a resident told the Washington Post. “They [Assad’s regime] can still commit massacres at any time.”

The US military warned their Russian counterparts before launching the attack, “to minimise risk to Russian or Syrian personnel located at the airfield” in the words of a Pentagon spokesman, again suggesting Trump’s team were mainly out to achieve dramatic effect. The Turkish foreign minister whose government seeks the downfall of Assad went so far as to call it a “cosmetic intervention”.

Despite this, there are real concerns including within the US ruling elite that the Trump administration is replicating its disastrous and inept policies on the domestic US stage with an adventurist military policy which could drag the US into a series of unwinnable conflicts. This is of course in stark contrast to the ‘isolationist’ doctrine Trump fought his election campaign on. The risks range from a potential standoff with Russia and Iran, the main backers of the Syrian regime, to an even more complicated and – if possible – more dangerous crisis on the Korean peninsular in which the two Koreas, China, Japan, and again Russia, could all be involved.

Rescuing Trump’s presidency

Whereas since the dawn of the 21st century, US imperialism has engaged in a series of one-sided, if politically disastrous, wars against vastly unequal opponents (Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya etc.), Trump now seems to be stumbling towards military engagements of a different magnitude which bring the US into conflict with nuclear powers such as Russia (over Syria) and China (should the US carry out Trump’s threat to act unilaterally against North Korea).

The US president, whatever he may believe, and US global power projection, do not operate in a vacuum. Actions like the attack on Syria and Trump’s escalation of threats against the unstable North Korean regime can upset the current fragile balance in these regions and trigger unforeseen consequences including the risk of a wider military conflict.

The overriding motive for Trump’s Syrian attack was clearly to salvage the shredded authority of his presidency after the worst start of any US administration perhaps ever. No US president has been this unpopular during their first months in office. Even after the military strike on Syria, Trump’s approval rating is just 40 percent with 50 percent of Americans disapproving.

The president’s Obamacare fiasco in March, when despite a crushing Republican majority in Congress, his attempt to scrap his predecessor’s inadequate healthcare programme collapsed, was the biggest in a series of humiliating setbacks for the new administration. Trump was forced to retreat in the face of a rebellion by the ‘Tea Party’ right wing of his own party, which denounced his proposal as ‘Obamacare-light’ for not making bigger cuts. This despite the fact that 24 million Americans would lose healthcare insurance under Trump’s proposals.

The incident laid bare the splits in the Republican party and Trump’s cabinet and raised doubts within the capitalist establishment about his ability to push through ‘Trumponomics’ with big tax cuts for the super-rich and a bonanza of infrastructure contracts for the big corporations, financed by deep cuts in public spending on social and environmental programmes.

Trump’s prestige also took a massive knock, which is an important factor in politics. The prospect of a ‘lame duck’ president gridlocked by elite-level factional warfare and challenged by waves of mass protests is not a happy one for US capitalism.

Initially, the capitalists were buoyed by Trump’s u-turns and abandonment of much of his populist election platform, especially his attacks on Wall Street which – predictably – have vanished into thin air. The New York stock market rose more in Trump’s first month than for any president since Franklin Roosevelt, adding more than US$2 trillion to US share prices in a frenzy of financial speculation which has since largely fizzled out.

Xi-Trump summit

The decision to stage the Syria attack during the two-day summit with Xi Jinping was also intended as a warning to the North Korean regime and Trump’s dinner guest Xi of possible US military action to stop Kim Jong-un’s nuclear weapons programme.

Prior to Xi’s arrival for these talks, Trump warned in a Financial Times interview that he was prepared to take “unilateral action” to eliminate North Korea’s nuclear weapons if China was not willing to increase its pressure upon Kim’s regime. This is part of stream of belligerent rhetoric from Trump officials, including Tillerson’s comments during a visit to South Korea in March that Washington had run out of “strategic patience” and was prepared to go to war.

Within days of the Xi-Trump summit the US moved its carrier battle group led by the USS Carl Vinson to the Korean peninsular, increasing tensions further. These moves, while possibly intended only as psychological warfare to wear down the Kim regime and press Beijing into imposing stiffer sanctions against it, represent a dangerous escalation of one of the world’s most complex and potentially deadly conflicts.

The Kim regime, a peculiar mix of Stalinist remnants and militaristic nationalism, has for reasons of regime self-preservation perfected the art of calculated irrationality – doing the unexpected or ‘crazy’ in order to shock and extract concessions from the imperialist powers and from South Korea. It is ironic that the politician who most imitates Kim Jong-un’s way of doing things is Trump himself.

The US strategy, if such exists, seems to be modelled on the Iran nuclear deal agreed in 2013, whereby economic sanctions led to a negotiated end of that country’s nuclear weapons programme. Note that during his election campaign Trump criticised the Iranian deal as a failure.

North Korea has faced a succession of sanctions since 2006 and these were tightened further in February this year in response to ballistic missile tests by the regime. China then decided to ban all coal imports from its neighbour, a significant step affecting around one-third of North Korea’s total exports.

The Trump administration wants to crank up sanctions into “what’s essentially a trade quarantine on North Korea,” an unnamed US official told Reuters. To succeed this strategy requires the full cooperation of the Chinese regime.

Conflicting interests

Beijing has grown increasingly uneasy with North Korea. But there are limits to how far Beijing and Washington can pursue a common strategy given what are fundamentally antagonistic interests in the Korean peninsular. Japanese imperialism’s use of the Korean crisis to push forward its own positions, possibly joining the US naval ‘armada’ off the Korean coast and recently calling for Japan to adopt an offensive (i.e. first strike) missile capability, is a further complicating factor for Beijing. So too is the US decision this year to base the THAAD (Terminal High Altitude Area Device) anti-missile system in South Korea. China is currently applying unofficial trade ‘sanctions’ against the Seoul government in protest over the THAAD deployment.

China fears the collapse of Kim’s regime which increased sanctions could trigger, the fallout from which could be colossal, including a refugee crisis spilling into China and even the possible fragmentation of the current North Korean state into warring factions laying hold of nuclear or chemical weapons. The South Korean capitalists also, for their own reasons, do not want to see the collapse of the North Korean regime.

It cannot be ruled out that Kim Jong-un will again call Washington’s bluff and engage in nuclear brinkmanship with further underground nuclear explosions or ballistic missile tests. This of course would ramp up the pressure on the Trump administration to react or risk being exposed as a ‘paper tiger’.

Furthermore, an election clock is ticking in that South Korea will elect a new president on 9 May, in the shadow of previous president Park Geun-hye’s spectacular fall from power – impeached and imprisoned after an estimated 10 million people took to the streets to remove her last year. Indeed, an element in the Trump administration’s plan may be to create a sense of crisis and imminent war on the peninsular to influence these elections.

With Park’s party – the traditional ally of US imperialism – running third, the race seems to be between the Liberal contender Moon Jae-in and Ahn Cheol-soo, a software tycoon who stands for “new politics” but in reality is emerging as the best hope for the discredited right wing establishment. Moon advocates negotiations and economic concessions to North Korea in return for a security agreement (a so-called ‘Sunshine policy’), whereas Ahn has shifted position 180 degrees adopting a pro-Trump stance against the North and also now supporting the deployment of THAAD.

Neither is the Iranian nuclear agreement necessarily a template for a deal with Pyongyang for the simple reason that the latter already has nuclear weapons. However scary is the reality that Kim – and Trump – possess WMDs, it’s the policies of successive US administrations that are responsible for this situation. Decades of US warmongering such as George W Bush’s “axis of evil” speech on the eve of invading Iraq have reinforced the ‘strategic paranoia’ of the North Korean generals. (Bush’s 2002 speech singled out Iran, Iraq and North Korea for US-sponsored regime change).

The grisly end that befell the dictators Saddam Hussein and Muammar Gaddafi, who were on the receiving end of US-engineered regime change, convinced Pyongyang of the need for a nuclear insurance policy. Trump’s strike on Syria will only have bolstered that view.

The “great chemistry” Trump claims between himself and Xi Jinping has done nothing to reduce national tensions or stabilise an increasingly dangerous geopolitical environment. The relationship between the world’s two biggest powers is in reality more strained than ever and this can face news tests and crises even in the space of the next months.

Conflicts, economic and political shocks are rooted in the global capitalist order, which since the worldwide crisis of 2008 has entered unchartered territory and seen the rise of dangerous populists like Trump. Only the working class, organising around a mass socialist alternative to sweep away the rule of the billionaires, can offer a way out.