In the 1930s Trotsky and his family were finding it impossible to secure safe refuge. Deported from France, refused entry into Britain, they moved to Norway.

This article describes how an alliance of Stalinists, fascists and ‘democrats’ ensured that Trotsky’s days of living on a planet without a visa were not over.

DEPORTED FROM THE Soviet Union by Stalin, in 1929, Trotsky, his wife, Natalia Sedova, and their son Leon Sedov, were hounded from one place of exile to another for more than a decade. In 1935 Trotsky and Natalya arrived in Norway, where they lived for eighteen months. The idyllic setting of their new home outside Hönefoss, as guests of the social democratic editor, Konrad Knudsen, was in stark contrast to the political storm brewing around them.

Under Stalin’s pressure, the country’s Labour government was to place Trotsky under house arrest and deny him all contact with the outside world at a critical moment – the opening phase of the infamous Moscow trials. “When I look back today on this period of internment”, Trotsky confessed later, “I must say that never, anywhere, in the course of my entire life – and I have lived through many things – was I persecuted with as much miserable cynicism as I was by the Norwegian ‘Socialist’ government. For four months these ministers, dripping with democratic hypocrisy, gripped me in a stranglehold to prevent me from protesting the greatest crime history may ever know”.

Norway’s Labour Party comes to power

TROTSKY ARRIVED IN Norway from France in June 1935, following the election of prime minister Johan Nygaardsvold’s Labour government. The French Radical government had threatened to deport him to one of their colonies. “It seemed I had a choice between Madagascar and Oslo”, Trotsky recalled. In Norway, he was greeted by some of the leaders of the Labour Party, who were anxious to meet the legendary founder of the Red Army. “From my very first contacts with the leaders of the Labour Party, I got a strong whiff of the stale odour of the musty conservatism denounced with such vigour in Ibsen’s plays”, he was later to recall.

The new Minister of Justice, Trygve Lie, urged Trotsky to give an interview to the party’s daily paper, Arbeiderbladet. Trotsky only agreed after assurances from the minister that this would not violate the terms of his asylum, which stipulated that Trotsky would not involve himself in Norway’s internal affairs. Expressing the genuine warmth towards Trotsky from the majority of Norwegian workers, Arbeiderbladet wrote that “the working class of this country and all right thinking and unprejudiced people will be delighted with the government’s decision. The right of asylum must not be a dead letter but a reality. The Norwegian people feel honoured by Trotsky’s presence in their country”.

Despite the weaknesses of Trotskyism in Scandinavia at that time, Trotsky soon settled into a busy routine, receiving visitors for discussions at the Knudsens’ home and corresponding with his co-thinkers around the world. Here he wrote The Revolution Betrayed, an analysis of the degeneration of the world’s first workers’ state. For the first time, he articulated in this book the need for a supplementary, political revolution in the Soviet Union to sweep away the privileged caste of bureaucrats and officials who had arisen due to the revolution’s isolation.

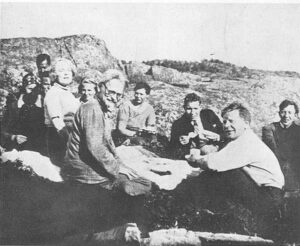

In August 1936 events at home and abroad took the kind of dramatic turn that only revolutionaries can fully grasp. From the outset, the Norwegian Liberals and reactionaries, including Major Quisling’s fascist party, Nasjonal Samling, opposed Trotsky’s presence in the country. Early in August a car-load of Quisling’s thugs forced their way into Knudsen’s home, posing as policemen and demanding to search Trotsky’s quarters. Trotsky and his host were away on a fishing trip but the Nazis were foiled by Knudsen’s daughter who, seeing through their disguises, barred the entrance to Trotsky’s rooms while her brother went for the police. On their way out Quisling’s men seized a few sheets of paper from a table near the entrance. They then issued a press statement claiming to hold documents which compromised Trotsky and were “in conflict with the undertaking he gave the Norwegian authorities to remain politically passive during his stay in Norway”.

The stolen papers were hardly sensational: an article on France which had already been printed in the American paper, The Nation, and a letter to a French Trotskyist. This ‘evidence’, however, would later be used to justify an astonishing U-turn by the government and, eventually, Trotsky’s deportation. Here we see a parallel with events today. The right of asylum comes under attack first from the extreme right, whose positions are then increasingly adopted by the mainstream parties – in the name of fighting… the extreme right!

Three members of Nasjonal Samling were arrested and charged for the break-in and theft of Trotsky’s papers. They had been spying on Trotsky round the clock for a month under orders from Hitler’s secret police, the Gestapo. ‘Gestapo behind Norwegian Nazi coup’, wrote the Swedish paper Dagens Nyheter (11 August 1936), reporting that copies of the stolen papers were sent to Germany. The Gestapo were anxious to know about Trotsky’s contacts among German exiles, while the Norwegian Nazis saw the campaign against Trotsky as a means of gaining national publicity in the coming parliamentary elections.

The Moscow Trials

TEN DAYS AFTER the bungled break-in, on 14 August, news broke that the ‘Old Bolsheviks’, Gregory Zinoviev and Leon Kamenev, along with fourteen co-defendants, were on trial for their lives in Moscow charged with ‘terrorism’. This was the start of the monstrous series of frame-ups known as the Moscow trials. Among other things, the defendants were charged with plotting to kill Stalin and forming an alliance with German and Japanese imperialism. According to Stalin’s prosecutor, the ex-Menshevik Andrei Vyshinsky, the leaders of this conspiracy were Trotsky and his son, Leon Sedov. Sedov, who was a member of the International Secretariat of the Movement for the Fourth International and at that time living in France, was murdered eighteen months later, aged 32, by agents of Stalin’s GPU (forerunner of the KGB).

Overnight the world’s press was full of Vyshinsky’s accusations. Dagens Nyheter ran the headline ‘Trotsky dangerous person even in Soviet Russia – planned murder of Communists’, reporting that he had “personally sent a number of terrorists from abroad to Soviet Russia”.

Trotsky hit back, “I can immediately brand the TASS (official Soviet news agency) statement about my terrorist activity as one of the greatest falsifications in the history of politics. I hereby declare that the accusations are completely untrue. For everyone who is familiar with recent political history it is beyond the slightest doubt that the report circulated by TASS stands in the sharpest contradiction to my ideas and my entire activity, which at the present time are devoted exclusively to writing.

“I emphatically assert that since I have been in Norway I have had no connection with the Soviet Union. I have not received here even a single letter from there, nor have I written to anyone either directly or through other persons. My wife and I have not been able to exchange even a single line with our son, who was employed as a scientist and has had no political connection with us whatsoever”.

The last reference was a desperate attempt by Trotsky and Natalia to shield their youngest son, Sergei, who still lived in Russia. Sergei was in no way involved in politics. Despite this, he was arrested and charged with the ‘mass poisoning of Soviet workers’ and shot in 1937.

The trial of Zinoviev and Kamenev was grotesque. The two old revolutionaries, morally and physically broken, signed their own death warrants by confessing to impossible crimes. “Even slander should make sense”, Trotsky commented. Zinoviev and Kamenev had already been imprisoned following the assassination of the Leningrad party chief, Sergei Kirov, in December 1934, a crime for which Stalin’s own GPU were in fact responsible. The Moscow trials were riddled with such glaring incongruities. “The Soviet press has so far not publicised anything on how they (Zinoviev and Kamanev) from prison, in which they’ve been held since January 1935, could still lead the opposition groups or how they could maintain links with the agents and spies of a foreign power”, wrote Dagens Nyheter (20 August).

All sixteen defendants were executed. Any faint hope that they might be spared was dispelled by Vyshinsky’s closing remarks: ‘I demand that dogs gone mad should be shot, every one of them!’

The bloody purges of the 1930s amounted to a one-sided civil war waged by Stalin to crush all traces of opposition to the rule of the bureaucracy. In 1936-37 at least eight million people were arrested and a million executed. Anti-communist publications like The Black Book of Communism, which argue that Stalin’s regime evolved naturally from Lenin’s, have great difficulty explaining why – in that case – Stalin was forced to liquidate the entire generation of Old Bolsheviks who represented a personal link to Lenin and the traditions of October. The show trials, relying solely on made-to-order confessions, were the means by which Stalin justified the purges.

That Trotsky, in absentia, was the main target of the trials, was no accident. He alone of the leaders of the October Revolution continued to fight for the ideas of Bolshevism and to advance a programme for the struggle against Stalinism. The GPU used torture and threats against the families of the accused in order to extract confessions which would implicate Trotsky and justify the repression. Some confessed in the faint hope they would be spared at the last minute. Those who could not be broken by the GPU were shot after bogus ‘secret trials’ as happened with eight senior Red Army officers, headed by the legendary Mikhail Tukhachevsky, who were executed as ‘agents of Hitler’ in June 1937. Three of the eight were, like Trotsky himself, of Jewish origin. This was the opening shot of a purge that would decimate the officer corps of the Red Army continuing right up to the German invasion of 1941. Trotsky warned that “the interests of Soviet defence have been sacrificed to the interests of self-preservation of the ruling clique”.

Government capitulates to Stalin’s pressure

THE MOSCOW TRIALS took the whole world by surprise, including the national sections of the Comintern. The Norwegian Communist Party organised a public meeting on 14 August, just hours before the news broke from Moscow, protesting against the fascist attack on Trotsky. Within days such ‘mistakes’ were corrected and l’Humanité, the newspaper of the French Stalinists, wrote that the Norwegian fascists had paid a ‘friendly visit’ to Trotsky!

Trotsky later confessed, “I felt as if I were in a madhouse”. He was determined to answer even the most ludicrous charges in order to leave no doubt as to his innocence, and to expose the motives and character of Stalin’s regime. “My terrorist activity has, according to the charges, been conducted in particular from Denmark, France and Norway. The crimes of which I am accused are punishable in these countries. I therefore demand that they take legal proceedings against me. It’s my duty to expose one of the worst crimes in world history”. (Dagens Nyheter, 26 August 1936)

On 27 August, the ministry of justice in Oslo issued a statement claiming that Trotsky had violated his asylum conditions. Suddenly he was completely encircled – fascists, Stalinists and now the Labour government, under Stalin’s pressure, wanted him silenced. He was asked to sign an undertaking that he would refrain from interfering ‘directly or indirectly, orally and in writing, in political questions current in other countries’. He refused to sign and was placed under house arrest, on Trygve Lie’s orders, and prevented from making public statements. The government, panicking at the thought of losing the election, was caving in to the combined pressure from Moscow, the Nazis and the owners of the shipping and fishing industries – who did not want to antagonise Moscow. As always when their class interests are at stake, the capitalists can dispense with noble sentiments like the right to free speech or the struggle against tyranny.

When Trotsky was called on 28 August to give evidence in the burglary trial of Quisling’s men, he found himself in the dock. Brought to the court under police guard, he was subjected to a two-hour interrogation about his political activity in Norway and whether he had criticised foreign governments. The judge then pronounced that Trotsky had, by his own admission, violated the conditions on which he had been given asylum. He was rushed from the courtroom to a meeting with Lie, who insisted that Trotsky sign a new undertaking, slightly modified from the day before, which included the following: ‘I further agree that all my mail, telegrams, telephone calls, sent or received by myself, my wife, and my secretaries be censored…’!

They wanted his signature because the government had no right under the Norwegian constitution to imprison Trotsky, who had not committed any offence. Lie, who later became secretary-general of the United Nations, was forced to obtain a royal decree to retroactively justify arresting Trotsky and Natalia – who at no time was asked to sign anything! Trotsky recalled that, “the ingenious minister of justice had only to fill this gap in the basic law of the land by inviting me, of my own free will, to ask for the chains and handcuffs. I categorically refused”. He told Lie that he was suffering from delusions of grandeur if he believed he could succeed where even Stalin had failed.

He was now placed under more stringent guard. His two secretaries, Erwin Wolf (who was later kidnapped and murdered by the GPU) and Jean Van Heijenoort, were deported. Some days later Trotsky and Natalia were moved to a new place of detention in Hurum. They were allowed no visitors and their police guard, responsible for censuring Trotsky’s mail, was under the command of members of Nasjonal Samling. One of these Nazis became chief of police under Quisling’s war-time government.

Trotsky summarised his situation: “The fascists attempt a raid on my home. Stalin accuses me of an alliance with the fascists. To prevent me from refuting his lies, he obtains my imprisonment from his democratic allies. And the result is that they lock us up, my wife and me, under the supervision of three fascist functionaries. No chess player, in his wildest fantasy, could dream up a better deployment of pieces”.

The detention of Trotsky and Natalia caused an outcry which was felt even within the state bureaucracy. This is why Lie relied on fascists to do his dirty work. When Lie paid Trotsky a surprise visit he received this warning: “You are paving the road for fascism. If the workers in Spain and France don’t save you, you and your colleagues will be émigrés in a few years like your predecessors, the German Social Democrats”. The minister had occasion to recall these words in April 1940 when Hitler invaded Norway.

A mockery of the right of asylum

WHILE THE LABOUR ministers always denied it, their persecution of Trotsky was a capitulation to Stalin. Trotsky was cut off from all contact with the outside world, unable to answer the vile slanders against him, unable to speak with his supporters. By imprisoning him, the Norwegian government gave Stalin an enormous propaganda weapon – if Trotsky wasn’t spreading terrorism from Norway, why had he been arrested? Vyshinsky wrote in the journal, Bolshevik, that Trotsky’s silence was proof of his guilt. When Trotsky, in an attempt to use the courts in order to be heard, decided to sue two newspaper editors (one fascist and one Stalinist) for slandering him, Lie intervened with a new decree stopping the legal action.

Leading government figures made it increasingly clear they wanted to be rid of Trotsky. At a cabinet meeting, Nygaardsvold said that if Trotsky didn’t accept the government’s new terms ‘we’ll send him to Siberia’. On 30 August, Soviet foreign minister, Maxim Litvinov, demanded Trotsky’s deportation. There was a real danger that the Labour ministers would hand Trotsky over to Stalin (just as Greece and other EU powers handed PKK leader Öcalan over to the Turkish authorities in 1999).

A debate raged over Trotsky’s case and its significance for the fast disappearing right of asylum. On 27 August 1936, an editorial in Dagens Nyheter asked, “Is the Norwegian government really absolutely certain that Trotsky’s activities during the last year lay within the agreed parameters of the right of asylum?… It’s above all a question of control”.

This article, published on the very day of Trotsky’s arrest, echoes the accusations of Stalin and Quisling. Then as now the bourgeois press and politicians declared themselves ‘impartial’ in the conflict between Stalin and Trotsky, yet in all practical actions sided with Stalin.

Thanks to Mexico’s decision to grant Trotsky asylum in December 1936, the door of his Norwegian cell was flung open after four months of agonising silence and uncertainty. Upon hearing of Trotsky’s departure the Soviet Ambassador sent flowers to Trygve Lie.