Hong Kong’s ‘Occupy Central’ leaders embellish the role of the middle class and ‘legality’ – ignoring key lessons from 1989

Dikang, Socialist Action

This article from the current issue of Socialist magazine, produced by the Chinese section of the CWI, takes up some lessons from the epic 1989 mass movement against the Chinese dictatorship, and how they apply to today’s democratic struggle. In Hong Kong a new initiative dubbed ‘Occupy Central’ has been launched by law professor Tai Yiu-ting, supported by the leaders of the main ‘pan democratic’ (bourgeois pro-democracy) parties. This plans for a mass occupation of the city’s business district to commence in 2014. The struggle centres on which electoral rules will apply for upcoming elections for the Chief Executive (head of government) in 2017, and the ‘Legco’ (pseudo parliament) in 2016 and 2020. Beijing has vaguely promised to allow a free vote (universal suffrage) starting in 2017, but – as CWI comrades warned – its ‘concessions’ fall a long way short of even the limited forms of democratic elections that apply in Western countries. CWI supporters welcome all proposals for mass struggle, including for a mass occupation, while stressing that this alone is not enough. The kind of struggle envisaged by the bourgeois ‘pan democratic’ tops falls far short of what is needed to break the resistance of the Chinese dictatorship. At the same time the political landscape in Hong Kong is becoming more complex and fragmented with the emergence of a small but vocal ‘autonomy’ movement that uses racist arguments against mainland Chinese, but has captured some support among youth especially due to growing discontent with the pro-government camp, but also with the ineffective and weak-kneed ‘opposition’ of the pan democratic leaders.

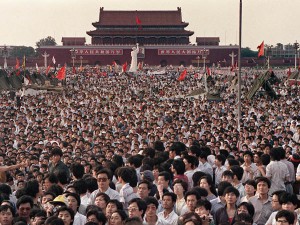

Tens of thousands will again flood into Hong Kong’s Victoria Park to commemorate the ‘6.4’ [June 4, 1989] massacre. For a new generation who weren’t even born in 1989, the annual vigil has become a mass protest against the unreformed and unrepentant CCP dictatorship, which perpetrated this atrocity to quell a movement that posed a threat to its survival. Rather than allowing even limited democratic openings, the CCP-state has built-up and modernised its repressive machinery, increasing the ‘internal security’ budget by more than 200 billion yuan in the past three years (exceeding its military spending).

A new Chinese leadership promises ‘economic reforms’ to please bankers, capitalists and right-wing international agencies like the World Bank, but explicitly rejects democratisation and what it falsely dismisses as ‘Western systems’.

The organisers of Hong Kong’s yearly candle-light vigil will again call for the mass anti-government movement of 1989 to be ‘vindicated’. But what does this really mean? Clearly, calling upon the dictatorship to apologise and confess to mass murder is like asking a vampire to stop drinking blood. The only credible way to ‘vindicate’ the heroic 1989 movement is to rebuild it! This means to prepare organisationally and politically for a new mass struggle in China and Hong Kong, and to insure the lessons of what happened in 1989 – how the CCP was able to defeat this movement – are learnt.

Has ‘Occupy Central’ learnt from history?

This year an analysis of these events is particularly relevant, following the launch of the ‘Occupy Central’ movement to increase pressure on the Chinese dictatorship over Hong Kong’s upcoming elections and long-awaited introduction of universal suffrage. This has aroused a lot of interest among those who want to take the struggle forward. Unfortunately, leading spokespeople for the ‘Occupy Central’ movement have clearly not learnt the lessons of the 1989 struggle, or more recent movements like ‘Occupy Wall Street’ and the mass revolutionary struggles against despotism in the Arab world. They stress the need to limit the coming struggle and reject “radical” methods that could “provoke” a hard line from Beijing. This sounds more like a renunciation of the 1989 struggle than any vindication!

Professor Tai Yiu-ting for example told the South China Morning Post (May 21, 2013) Occupy Central is “a restricted and conditional plan for civil disobedience”. The desire to “restrict” the struggle shows a complete underestimation of the scale of the challenge we face: to inflict a defeat upon the CCP dictatorship. If the 1989 movement did not win concessions from the CCP regime despite its truly momentous sweep, how will Tai’s “restricted” model achieve this aim? The pan democratic leaders who have jumped aboard Occupy Central, seeing it as a political lifeboat, have done so with two aims: to pump up their own fading influence over the coming struggle and to try to block more radical mass struggle that would press for a real and irreversible democratic transformation.

In a parallel development, the organisers of the annual ‘6.4’ commemoration have this year for the first time discarded the slogan ”End one-party rule”. In its place they have adopted the slogan ”Love the country, love the people.” This reflects a trend among the pan democratic leaders towards political accommodation with the CCP dictatorship in the vain belief it will respond with meaningful concessions over universal suffrage. On the contrary, with the pan democrats already softening their positions, this will increase Beijing’s resolve to make no more than superficial changes (for a fuller analysis see our editorial ‘Great debate over Occupy Central’, Socialist magazine, issue 21).

Tai unashamedly stands for a “middle class movement”. He even wants to limit the participation of youth – turning the experience of 1989 upon its head! Again, these ideas reflect the ‘moderate’ pan democrats’ fear that the coming struggle will turn to radical methods. The comments of Occupy Central spokesmen on the issue of non-violence give an extremely misleading and unbalanced view of anti-government protests in Hong Kong over many years – in which hardly a flowerbed has been trampled! Would the struggle of 2003 against Article 23 [hated security legislation involving curtailment of political freedoms] have succeeded by adopting a similar “restricted” approach? Would 10,000 protesters have been more effective than 500,000? It should be remembered that the self-styled moderate democrats also in 2003 wanted a compromise with the government and sought to avoid a showdown, as they did again in 2010 when they voted for the CCP-approved electoral reform.

The student leaders in 1989 did not have a clear programme for challenging and presenting an alternative form of government to the dictatorship. Their demands against autocracy and for the punishment and removal of corrupt officials and princelings resonated with the masses and set millions of people in motion. These demands initiated the struggle, but more was needed to continue it and carry it to a victorious conclusion. A clear programme was needed, including the demand for immediate elections to a revolutionary constituent assembly, organised through mass committees in all cities, for a workers’ and poor farmers’ government ending one-party rule and guaranteeing full democratic rights as well as urgent measures to raise wages, pensions and the general conditions of the masses. This would also include revolutionary fraternisation with the rank and file soldiers, appealing to them to join the struggle and refuse to carry out the orders of the ‘Butchers of Beijing’.

Breaking the law?

The student leaders in Beijing, despite many political shortcomings, were prepared to defy the antidemocratic ‘legality’ of Deng Xiaoping and the dictatorship. The infamous April 26 Editorial in People’s Daily (reportedly written by Deng himself) ordered the demonstrators to end their occupation of Tiananmen Square and return to school. It banned communications between schools and – significantly – banned students from linking up with workers. It reiterated a total ban on students’ and workers’ independent organisations. The fighters of 1989 refused to obey Deng’s edict. They understood the movement would be doomed to fail if it was bound by the ‘legal’ restrictions of the CCP-state.

Similarly, the youth in Tiananmen Square put forward political demands that were ‘treasonable’ or ‘seditious’ under China’s law. They demanded democratic rights and an end to autocracy. This contrasts with Hong Kong’s ‘moderate’ pan democratic parties who years ago dropped opposition to one-party rule in China. The logic of this political accommodation is seen today when – before the battle has started – the pan democrats have begun to water down their immediate demands for the 2017 elections.

This is most clear on the issue of a nomination committee for the Chief Executive election, something that no genuine democrat can accept [yet the ‘Alliance for True Democracy’ consisting of the main pan democratic parties has accepted this]. Any nomination committee, no matter how it is constituted, is designed to reduce the influence of the masses and force ‘compromise’ decisions that benefit the ruling elite. This is because it is easier for a government or ruling class to manipulate a closed chamber – even one that has been ‘elected’ – than to manipulate mass elections in which anyone is free to run.

Contrasting sharply with the stance of the 1989 Tiananmen protests, ‘Occupy Central’ spokespeople have turned ‘legality’ into a sacred cow for their movement. Furthermore, they deliberately mix up ‘legality’ with ‘non violence’. Yet as 1989 and other mass struggles show, these issues are not at all identical. The massacre of June 4 and the CCP’s subsequent wave of terror were legally sanctioned. Conversely, the action of 100,000s of protesters in returning to Tiananmen Square after the April 26 Editorial ‘order to disperse’ was an openly illegal act. Similarly, when we read that the use of pepper spray at demonstrations by Hong Kong police has doubled in the past two years, this is a legally authorised rejection of ‘non-violence’.

It was not “illegality” that led to the massacre in 1989 – it was the potential of the mass movement to bring down the dictatorship. It is a law of history that any serious mass movement from below will face repression by an authoritarian regime. This does not mean that struggle is hopeless or should be limited, but it means a strategy and leadership is needed to escalate the struggle and secure victory.

Every legal system is based on defending the interests and privileges of the ruling elite, whether this be capitalists or ‘communist’ bureaucrats. Even in Western so-called ‘democracies’ the independence of the law courts is a myth – political decisions and the pressure of the ruling class is reflected at every level. Hong Kong is not even a ‘democracy’ on Western lines, and we have seen a number of court rulings in recent months – against the dockworkers’ strike, overturning the right of abode for migrants, imposing stiffer punishments upon ‘radical protesters’ – that reflect the wishes of the ruling class for a more repressive stance against the working class and those who challenge the existing system.

Working class is the key to victory

By talking up the role of the middle class in the coming democracy struggle, the ‘Occupy Central’ leaders are following not the strongest traditions of the 1989 struggle, but repeating some of its most serious mistakes. The student leadership in 1989 took the position that workers should be discouraged or even physically kept out of the movement. In their defence, this was an error committed mostly in the first stages of the struggle. The position changed later, based on the experience of the mass movement, with the best of the students realising the need for united struggle with the working class. There are no such excuses for the blinkered approach of the ‘Occupy Central’ leaders.

In 1989, as Maurice Meisner explained, “some of the class prejudices [of the intellectuals towards the working class] had filtered down to students as well, many of whom opposed participation of workers in the Democracy Movement on the grounds that workers were undisciplined and prone to violence. The participation of workers, it was suggested, would provide the government with an excuse to use force…” (Mao’s China and After, 1999)

Call for a general strikeFrom the middle of May 1989 the specific weight of the working class within the mass struggle grew enormously. The regime sensed it was losing its base of support in the factories as workers were radicalised. One incident sums this up. After students at the Central Academy of Fine Arts erected the ‘Goddess of Liberty’ statue (a controversial project some interpreted as exhibiting pro-Americanism), CCP officials planned to send in a contingent of steel workers from Beijing’s biggest industrial plant to demolish the statue. This would have been possible – physically – at nighttime when numbers of protestors in the square were lower. But the plan was abandoned because the CCP bosses and their police spies feared “it would backfire and only increase worker support for the movement.” (Quelling the People, Timothy Brook, 1992)Workers were looking for a means to carry the struggle forward, realising that a mere protest to ‘get the attention of the government’ was not enough. The struggle had moved beyond this. The badly fractured CCP-state was fighting for its survival and – in Deng’s coterie – was preparing to settle the issue in blood. Unfortunately, there was no conscious revolutionary organisation of workers that could focus and speed-up the clarification of political tasks to allow the working class to takeover the leadership of the movement, which could have secured its victory.

The most militant sections of the working class began to raise the demand for a general strike in support of the students’ democratic programme. Tragically, the student leaders opposed the strike call as “too radical”. This is one of the most relevant lessons for the situation in Hong Kong and China today. When socialists raise the idea of strike action, as we did during the mass anti-brainwashing struggle of 2012 (calling for a city wide school strike), it is because such methods – especially if led by the working class – correspond to what is needed in a struggle against a despotic regime. This is not at all the same as advocating violence, or flirting with this idea as some populist politicians do (Chin Wan-kan for example).

Of course the pro-government camp and capitalist tycoons will claim this anyway. Today they use the same arguments against Occupy Central as they used against the 500,000-strong mass protest of July 1, 2003 – that society will descend into ‘anarchy’ and the economy will be ‘destroyed’. The capitalists are as much a block to democratic change as the CCP regime. Deng Xiaoping after all is the hero of the Hong Kong tycoons despite the ‘small detail’ of the carnage of June 4. This is why the capitalists’ undemocratic power over Hong Kong’s economy must be broken through real socialist policies.

During the dockworkers’ strike of April-May, billionaire Li Ka-Shing’s legal representatives lied about ‘disorderly’ protests and safety issues to gain court injunctions against the strike. While the ruling class is preparing for brutal measures, its media and propaganda machinery attempts to portray those fighting for democracy and in defence of workers’ living standards as bent on ‘chaos’ and ‘violence’. Well-organised and democratically-run mass actions can undercut this propaganda, while at the same time winning mass support for the type of radical measures – strikes, general strikes, blockades, mass demonstrations and democratic popular committees – that are needed if the movement is to succeed.

The mass struggle in 1989 was crushed before it could rise to this level. The Deng wing of the CCP was more resolute (prepared to wade through blood) and more organised, while the mass struggle despite its incredible heroism and initiative lacked the necessary component of a revolutionary party, based upon the working class, which could have equipped it for the task of overthrowing the dictatorial regime. “Those who cannot learn from history are doomed to repeat it,” warned George Santayana. Unfortunately, for the leaders of ’Occupy Central’ it seems the lessons of 1989 are a closed book. Socialists, however, base ourselves on these lessons written in blood. This is why we stand for full and immediate democratic rights through militant mass struggle, not cosmetic changes or deals that prolong the life of the dictatorship.