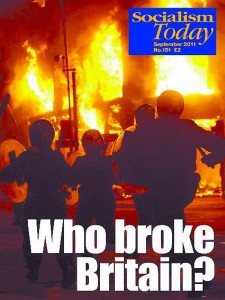

August’s explosive events revealed a class society in crisis

Sarah Sachs-Eldridge, Socialist Party (CWI England & Wales), first published in Socialism Today

On Thursday 4 August police shot dead Mark Duggan on the streets of Tottenham. Local outrage at the killing was the spark for what followed in north London but the conflagration – the most severe social disturbances in a generation – spread far and wide across English cities. SARAH SACHS-ELDRIDGE looks at the seven days in August that raise the question, in response to the establishment politician’s moral posturing: who broke Britain anyway?

AUGUST’S EXPLOSIVE EVENTS have exposed the reality of British capitalism: the enormous wealth gap, persistent racism, and the impact of the cuts, particularly on services such as fire-fighters and youth facilities. It has revealed a class society in crisis where all but the very rich are struggling and massive anger, boiling below the surface, can burst out at any time.

The rot starts with the pampered and corrupt millionaire government and the super-rich. While millions of working- and middle-class people struggle with ever increasing food and fuel bills and shrinking incomes, the richest 1,000 individuals in the UK have amassed a combined wealth of £396 billion. With that they could pay for chancellor George Osborne’s £81 billion of cuts nearly five times over. But the Con-Dems, like their counterparts across the world, are intent to gouge the cost of deficits, resulting from enormous bank bailouts, from working-class communities and families.

Departing for their summer break in July, the Con-Dems faced gathering storm clouds. The Murdochgate scandal has exposed corruption in the police and the big-business press. It leads directly to prime minister David Cameron through his association with former News of the World editors Rebekah Brooks, a personal friend and, particularly, Andy Coulson, another ‘friend’ and a former Cameron employee.

Images of furious fires and seemingly out of control crowds – social disturbances on a scale and ferocity unseen for a generation – sent a wave of shock, as well as fear through the country. But these events were not unpredictable. In mid-June many newspapers were talking about a summer of discontent. None had imagined such a sudden and fast-spreading outburst of rage from young people, normally invisible to the general public.

These events have been discussed and commented on in all corners of the world. Many have speculated on the impact on the Olympics, planned for 2012 in the very areas where rage erupted. Symptomatic of their lives, for most youth in the area, the Olympics have brought neither jobs nor the opportunity to partake in the sporting spectacle, given ticket prices and the need for a healthy bank account to even try.

The initial spark was the fatal police shooting of Mark Duggan in Tottenham, north London, on Thursday 4 August and the subsequent cover-up by the so-called Independent Police Complaints Commission. When hundreds protested outside Tottenham police station on the following Saturday their demands for justice were ignored. Frustration spilled over. Buildings were burnt and shops looted.

In Hackney, it was provocative and aggressive police stop-and-search action on 8 August that ignited the explosion of anger. These were complicated events, reflecting a multitude of issues. The characteristics of the outbursts varied from area to area. In Manchester and Birmingham, city centres were the focus. In London, it was areas local to those arrested. The Guardian’s analysis of ministry of justice data from the courts disproves the claims of Tory work and pensions secretary, Iain Duncan Smith, that ‘outsiders’ and ‘organised gangs’ were largely to blame. Tory attempts to classify all involved as criminals aim to hide the fact that working-class young people have so much to be angry about.

It was that abundance of flammable material, a generation robbed of its future and treated like criminals, particularly young black people, that led to the rapid spreading of the eruptions of anger across England. This included growing anger over the number of deaths at the hands of the police. More than 300 deaths have taken place over ten years and not one officer has been charged. In Brixton, the hated ‘sus’ laws were a major source of resentment that contributed to the 1981 riots there.

Today, black people are 26 times more likely than white people to be stopped and searched under the provisions of the 1994 Criminal Justice and Public Order Act. That is a further condemnation of the police’s inability to act on the 1999 Macpherson inquiry into the murder of Stephen Lawrence which confirmed the existence of institutionalised police racism. In 2010, 48% of young black people were unemployed while the rate among white young people was 20%.

On the scrapheap

BUT, WHILE RACISM was a factor, certainly in the initial flare-up, it was not the major issue behind August’s outbreaks. Footage of stand-offs against the police involving black, white and Asian youth shows young people whose lives are boxed in by poverty and dogged by the police feeling that they could challenge those conditions. The Financial Times quoted a young person from Croydon: “Where are we supposed to go to meet? We just get pushed around wherever we go”. He continued: if “they tell me where they want me to go where I can just hang out with my mates without a babysitter, I’ll go there”. Now many are facing jail.

Joblessness is a key factor in this outburst of rage. The Guardian’s analysis backs this up: fewer than 9% of those charged in the special 24-hour courts are in full-time work or study. And August’s unemployment figures show a dramatic increase, with unemployment among women at Thatcher-era levels. On average, 1,200 joined the dole queue every day in July. For young people the outlook is devastating: one million have no jobs, 100,000 have been out of work for more than two years, and 36.7% of 16-17 year-olds are unemployed. Society has cast these young people onto the scrapheap and abandoned them.

Couple this with the looting of the Education Maintenance Allowance (EMA), the skimpy, means-tested payments of up to £30 a week, which at least enabled many 16-18 year-olds to continue in education. A survey by the National Union of Students from 2008 found that around two-thirds of recipients would not be able to continue their studies without it. The Con-Dems’ scant replacement is tokenism. August has also seen the A-level results, with record high grades. What a criminal waste that, on the basis of cuts, 250,000 young people will be chasing 40,000 university places in ‘clearing’. University is increasingly being cut off to all but the rich, with average student debt estimated to be over £50,000 within a few years.

The looting of cheap supermarkets such as Aldi and Tesco for items like nappies and food reflects deep poverty. Clasford Stirling, a youth worker who runs the football club on the Broadwater Farm estate in Tottenham, points out that some young people “didn’t even bother covering their faces. They’re not trying to rob the banks, they’re going to Currys, they’re stealing trainers, they’re that poor that they’re risking going to jail for a flat screen television”.

None of these conditions are new. But normally the frustration is vented within the confines of working-class areas, which can result in drug use and crime.

Hijacking the fightback

ON THE OTHER end of the spectrum, dragged back from their lavish holidays, the Tories have leapt on August’s explosions of anger as an excuse for ramping up repression and stepping up their anti-working class attacks. They hope that pointing the finger of blame at sections of ‘broken Britain’ will permanently undermine the struggle against cuts. Has the establishment politicians’ adage of ‘never letting a serious crisis to go to waste’ ever been more strenuously pursued?

Despite Osborne’s increasingly pathetic sounding assurances, the economic outlook is grim. As the cuts hit home, support for the Tory/Liberal brutal cuts agenda and confidence in the government’s economic policy is on the slide. On 4-5 August, a YouGov survey for the Sunday Times found that 35% had less confidence in the government’s economic strategy than in February. Over a quarter answered that there was no change, they still had no confidence in the strategy.

Initially, no one from the government was available to comment on the outpouring of rage on England’s streets. Deputy prime minister, Nick Clegg, was the first minister to give up his holiday, but home secretary Theresa May launched the government line on 8 August: “No excuse for thuggery, for looters or violence”, she said. TV news provided a terrifying, endless loop of raging fires in Hackney and Croydon as she appeared repeating the mantra.

May was intermingled with sound bites from Diane Abbott, a so-called Labour left MP, who demanded curfews, with no attempt to explain the conditions that led to the anger or the events that sparked its flare-up on the streets. Savage Con-Dem cuts, sitting atop decades of neo-liberal attacks that have seen wages stagnate and public services privatised, are the underlying factors.

But nothing can take away from the tragedy of the loss of life that has taken place, as well as the ruin of people’s homes and small businesses. The destructive acts that resulted in the deaths of six people must be condemned. Similarly, those that left over 100 people homeless and damaged shops, pubs, clubs and restaurants in 28 town centres. All must be re-housed by local councils, and small businesses compensated by the government immediately.

Forced to recall parliament for the second time this recess, Cameron, as The Economist put it, “aired his old trope of the ‘broken society’ but no new ideas”. He talked of “pockets of society that are not just broken but frankly sick”, and the causes of the riots as “criminality pure and simple”. “Our security fightback must be matched by a social fightback”, he said, ripping off the language of anti-cuts campaigners.

Support for repression?

THE QUESTION IS: will the Tories be successful in their attempt to hijack the ‘fightback’ and turn society against working people generally, and the most excluded and marginalised in particular. In the long run the answer is no. This is a fundamentally weak and unpopular government, facing an economic disaster. But widespread fear and shock led to a sense of insecurity. Hoping to ride this wave, the Tories have raised a variety of repressive measures, including water cannon. While sermonising against violence, Cameron has hypocritically recommended the use of rubber bullets for ‘riots’. Rubber bullets have been used in Northern Ireland since 1969 as a ‘deterrent’. In that time, 17 people including eight children have been killed by them.

Hugh Orde, president of the Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO), has clashed with the Tories over this. He has written that water cannon are “useless” apart from when aimed at “static crowds”. Recent events in England were not organised political actions as those in Egypt earlier this year, which faced water cannon, tear gas and bullets from the regime. And right-wing politicians use the riot label loosely. Last December, Heidi Alexander, Labour MP for Lewisham East, referred to a protest at Lewisham town hall by trade unionists and local campaigners against £20 million of local government cuts as a riot and, disgracefully, riot police were called in by the Labour-led council.

In the short term, the Tories may find some support for a tough response: 216,180 people have signed the e-petition calling for “convicted London rioters” to lose all benefits. On the other hand, that is less than half of those who marched against cuts in jobs, services and benefits on 26 March, and a third of those who took collective strike action against attacks on public-sector pensions on 30 June.

The government response on the e-petition website explains how it plans to ramp up its existing attacks on benefits, such as considering “whether further sanctions can be imposed on the benefit entitlements of individuals who receive non-custodial sentences”, and “increasing the level of fines which can be deducted from benefit entitlement”. The Con-Dems are already in the process of removing housing and disability benefit from tens of thousands of people, threatening major increases in homelessness and spiralling poverty.

They have already agreed to mete out ‘collective punishment’ by evicting the families of anyone charged for ‘riot-related offences’. Tory-controlled Wandsworth council in south west London has already served notice on the mother of an 18-year-old charged with violent disorder and attempting to steal electronic goods.

A YouGov poll, conducted on 10 August, showed that 90% of British adults supported the use of water cannon, 78% were in favour of the use of tear gas, and a third agreed that police should be able to use plastic bullets against rioters. However, given their deep unpopularity, there has been no discernable increase in Tory support in the polls at this stage. Two Sun/YouGov surveys of voting intention on 8-9 August and 17-18 August showed support stubbornly stuck at 36%.

Not so clear cut

ANGER WAS DIRECTED at Con-Dem politicians who dared to take to the streets. Clegg was booed and heckled in Birmingham. London mayor, Boris Johnson, was unable to answer when asked how young people would get vital job-seeking support when Connexions advice services were shut down.

Within only a fortnight of the first events there is growing concern about the harsh sentences being handed down to the thousands arrested. Although the Tories deny that they have intervened, the heavy sentences are widely seen as a political response, and that crimes against property are particularly severely punished. Two young men have been given four years for failing to organise a riot – posting Facebook messages to which no-one responded – in their local town centres. This is the same length of sentence given for recent convictions for rape or, in one case, being part of a £10 million heroin supply network. The Socialist Party has called for the setting up of a democratically run inquiry into the riots involving elected representatives of trade unions and community organisations, that could also set the parameters on how the offences are dealt with, with the right to review sentences already imposed.

There has been disagreement among coalition politicians, even within the two parties. While the Tories have been banging the ‘law-and-order’ drum they have insisted that the cuts to the police go ahead. But Johnson, with London elections next year on his mind, told BBC Radio 4’s Today programme: “This is not a time to think about making substantial cuts in police numbers”.

Working-class people in the areas affected have been frustrated by the lack of police presence to defend their homes and livelihoods. Even young people express frustration that the ‘service’ is not available to them when they require protection and help. Fundamentally, the police are a part of the state machine and act in its interest. They are widely hated for that role. We need police accountability through democratic control, with elected committees involving representatives of local people and trade unions.

While Clegg has generally marched in line with the Tories, some Lib Dems have been uneasy about the sentencing and about the moves to evict families. The Tories appear to be unmoved by their partners’ queasiness. They know, as does the dog on the street, that the Lib Dems are too broken to consider triggering a general election and have no option but to shut up. When asked by The Independent how the Tory right wing would react to Clegg’s proposals to conduct interviews to establish why anger erupted, one Tory minister replied: “Oh they don’t mind all that as long as they know the rioters are going to have their goolies chopped off”.

Filmed amid the fires in Hackney, Abbott asked: “who is going to give jobs to people in these communities?” That’s the question that a lot of people in her borough of Hackney ask, where there were fewer than 500 job vacancies for more than 11,000 claimants. But her question also summed up a key part of the government’s line: placing the blame for unemployment and the problems working-class people face on families and individuals rather than on the millionaire Con-Dems and the rich and powerful people they represent.

Cameron talked about putting “rocket boosters” under the “clear ambition” to “turn around the lives of the 120,000 most troubled families in the country”. This and his other big idea, the ‘Big Society’, are ideological justifications for cutting back on state provision of public services, that families should be responsible for their own welfare and suffer the consequences. He is echoing his guru, Margaret Thatcher, who famously claimed that ‘there is no such thing as society, just individuals and families’.

Duncan Smith has talked about investment in early years interventions. But the Con-Dems snatched away the baby element of the tax credits, the health in pregnancy grant, and cut back on Sure Start provision. To claim they intend to support poor and vulnerable families is sheer lies and hypocrisy. Instead, they are criminalising a generation of young people, locking up many with no previous record in overcrowded ‘colleges of crime’.

Capitalist values

SEEMINGLY WITHOUT IRONY, Cameron writes in The Daily Express: “There are deep problems in our society that have been growing for a long time: a decline in responsibility, a rise in selfishness, a growing sense that individual rights come before anything else”. These are the very qualities that are promoted and respected in the capitalist society he defends.

Just a few minutes walk from Tottenham police station is Tottenham Hotspur football ground at White Hart Lane. Current manager, Harry Redknapp (previously the manager at Portsmouth FC), is a director of a housing company, Pierfront Development. Portsmouth council has a housing waiting list of 2,553 applicants, but this company has been allowed to flout legislation that demands all housing developments include cheaper social housing. Pierfront will pay less than a quarter of the funding for the agreed number of affordable housing units. Even a Lib Dem councillor had to describe it as “simply profit before people’s lives”. This is just a small company on a small scale doing what major companies do on a major scale every day.

Even right-wing commentators like Peter Oborne in The Telegraph have condemned the “almost universal culture of selfishness and greed” among the super-rich, including expenses grabbing MPs. But he harks back to the ‘good old days’, saying that “the last two decades have seen a terrifying decline in standards among the British governing elite”. Of course capitalism, built on the wealth accumulated by slavery, is a brutal, bloody system that has always been based on the private ownership of wealth by the few and massive exploitation. What Oborne is referring to is the decades of neo-liberal policies in which today’s young people have spent all their lives.

‘Greed is good’ has been the motto. The state provision of services, jobs and utilities has been privatised in the interests of profit, resulting in cuts, insecurity and soaring prices. The share of wealth going to the working class has been slashed with tax concessions for the rich and virtual wage stagnation as trade union rights have been attacked.

Not only have the super-rich looted wages and public purses, they are hoarding their wealth, finding no profitable outlet for it. Instead of fulfilling their role in investing in production, providing jobs, the capitalists are buying gold, the only safe place for their riches, given the weakness of markets as cuts hit consumer spending.

As Karl Marx first explained, capitalism is an anarchic and chaotic system. In Britain, 2.5 million people have no job while an estimated £60 billion sits in British banks ‘waiting to be invested’ in new businesses, unspent because of ‘weak confidence’.

Mass civil disobedience

RIOTS, ALTHOUGH A chaotic and inchoate expression of protest, have not changed the world. Some on the left, such as the Socialist Workers Party, have written and spoken about looting “by poor working-class people” being a “deeply political act” (Socialist Worker, 13 August), that the looters were “expropriating the expropriators”, effectively redistributing wealth. This makes a mockery of socialist ideas that a mass working-class struggle has the potential to replace the capitalist system with one in which the resources of society are democratically owned and controlled by the working class with a plan to meet the needs of all.

Unfortunately, given the ideological shift to the right by the mass social democratic parties and many trade union leaders over the last two decades, Marx’s ideas are not widely known and understood, especially among Blair’s children and Thatcher’s grandchildren, today’s young generation. The recent explosive events show despair and the absence of understanding the potential power of working-class people to, not just express anger at our conditions but to change them, including bringing down the government.

Most of those who raged against the police and looted shops were not born when the mighty anti-poll tax battle was won at the beginning of the 1990s. That movement, led by the Socialist Party’s predecessor, Militant, was fundamentally based on mass, organised ‘law-breaking’. Under the hated and unfair poll tax, every adult was charged the same rate, massively penalising working-class people. Huge numbers simply could not afford it. But having succeeded in defeating the heroic miners’ strike in 1984-85, Thatcher presumed that she could take on the entire working class at once, threatening brutal repression, prison and bailiffs to anyone who did not pay. But the movement she provoked ultimately removed her from power.

On the left and right there are claims that the riot at the end of the mass anti-poll tax demonstration in London in March 1990 was the key to the victory. That violence had been triggered when the police launched an all-out attack on the demo. But the movement’s victory was in fact achieved through organising democratic local, regional and national anti-poll tax federations that painstakingly built confidence in the tactic of non-payment. Eighteen million people refused to pay the poll tax on an organised basis. This made it unworkable. Although the tax was brought into law, within a couple of years it was removed from the statute books.

One aspect of the anti-poll tax movement was the organisation of ‘bailiff busting’ teams which, without Twitter or mobile phones, developed phone trees and networks to protect the homes of non-payers from Thatcher’s henchmen – the bailiffs in England and Wales, the sheriff officers in Scotland. Such organised defence of communities, with elected organising committees, provide a useful model for community self-defence.

The big question

IN 2006, CAMERON said: “Understanding the background, the reasons, the causes. It doesn’t mean excusing crime but it will help us tackle it”. Needless to say, this approach is being ignored. Comedian Russell Brand, surprisingly wisely, pointed out: “I remember Cameron saying ‘hug a hoodie’ but I haven’t seen him doing it. Why would he? Hoodies don’t vote, they’ve realised it’s pointless, that whoever gets elected will just be a different shade of the ‘we don’t give a toss about you’ party”.

The absence of a political voice for the working class has been a weakness of the anti-cuts movement and these events further emphasise that. David Lammy, Labour MP for Tottenham, has put himself around in the aftermath of the riots but neither he nor his party provide any alternative to the Con-Dems. Labour deputy leader Harriet Harman has muttered a little about the effects of the cuts to EMA on young people. They have argued, like Johnson, against police cuts. Fundamentally, however, New Labour supports the slashing of public spending. New Labour’s last chancellor, Alistair Darling, made a pre-general election promise to implement cuts worse than Thatcher’s. Building a new workers’ party is clearly an urgent task.

There was a well-written article on the publicfinances.co.uk website which pointed to many of the contributing factors behind August’s events. Disappointingly, it finished by asking: “The big question is, where to now?” The author was named as ‘Lewisham resident’ Heather Wakefield. Wakefield is also the head of the Local Government Service Group of the UK’s largest public service trade union, Unison, representing over 700,000 of the union’s 1.4 million members. Why isn’t she providing an answer to ‘the big question’. The conditions for further outbreaks of anger remain and a clear response from the trade union movement is required, not just passive commentary.

The August events can be seen, in some ways, as the second call for back-up from the youth to the TUC trade union leadership. In November and December 2010, tens of thousands of school, college and university students protested against education cuts. Breaking the consensus that the cuts were necessary they inspired millions to support them. But they faced demonization and brutal policing, including mass arrests and kettling. Shivering inside a freezing nine-hour police cordon, students asked where the trade unions were, how come they had not supported them and joined the demonstrations? The Socialist Party called on the TUC to organise a mass demo before Christmas to provide the angry young people with a channel for their anger, and link them with the wider struggle against public-sector cuts. This was delayed by five months, until 26 March. Then the summer came. A number of cuts had gone through – particularly for youth services, EMA, etc – and still nothing had been organised to follow up the March demo by the TUC leadership.

The trade unions must reach out to young people – workers, students and the unemployed. This requires a programme around which they can fight. The demands of Youth Fight for Jobs (YFJ), with the support of six national trade unions, can be very attractive: reopen and expand youth services; nationalise the banks and use the money to create jobs; government investment in house renovation and building to provide cheap social housing; no cuts in benefits and end lower youth rates. These must be combined with a defence campaign against the heavy-handed sentencing and ramping up of repression.

It is not the case that every young person will be won to such a campaign immediately. And it does not mean that there are not racist, sexist, individualistic and other poisonous ideas among them. Indeed, in the absence of an alternative being provided, in the context of deteriorating living conditions, those reactionary ideas can be nurtured under capitalism, and individual, nihilistic or terroristic tendencies can develop which harm working-class people and do not advance the struggle.

Tariq Jahan, the father of one of the young men killed in Birmingham, has been widely praised for his call for community unity, guarding against a racist backlash. Five thousand attended the rally in an area where people know the cost of ethnic tension. However, it is working-class unity and organised struggle that is required to not only guard against a fracturing of society but also to build a mass movement that takes society out of the hands of the greatest looters, those who ‘break society’, the capitalist class.