How serious is Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption drive?

Vincent Kolo, chinaworker.info

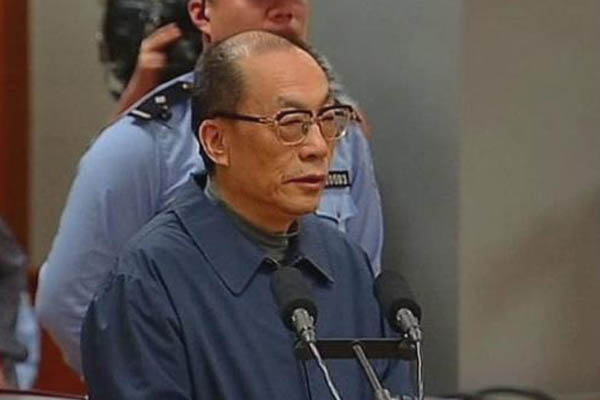

Liu Zhijun, who spearheaded China’s gargantuan high-speed rail programme, was tried for corruption on June 9 in Beijing. To say Liu, the former Minister of Railways, was corrupt is something of an understatement. No fewer than 477 court files detailed his corrupt practises spanning more than two decades. Eleven associates were named as having bribed Liu to gain job promotions or business contracts.

Yet his court appearance miraculously lasted less than four hours – evidence, if such was needed, that the trial was purely for show. This type of “high-speed justice” is typical in such cases, with courts rubber-stamping decisions reached elsewhere within the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) apparatus, and defendants quickly spirited away before they can fluff their lines.

According to the official Beijing Times, assets confiscated from Liu included 374 apartments (worth around 800m yuan or US$130m), 16 vehicles, 612 works of art, plus company stocks. The newspaper also reported that from cases related to Liu’s abuse of power, cash sums of 795.5 million yuan, HK$85 million, US$235,000 and 2.2 million euro were seized. Converted at today’s exchange rate this cash haul totals 882 million yuan. At the time of his arrest, CCTV reported Liu had taken up to one billion yuan in bribes.

“Great Leap Liu”

Yet these hefty sums were not included in the prosecutor’s case against Liu. In court he was charged with – and tearfully confessed to – accepting bribes worth 64.6 million yuan between 1986 and 2011. This represents a mere fraction of Liu’s illicit gains. Not for the first time in China, the real significance of this trial lies in what has been concealed, rather than what has been revealed. As in other recent high profile court cases, those of Gu Kailai and Wang Lijun (last year in August and September respectively), and perhaps also the upcoming trial of Bo Xilai (whenever that may be), the prosecution has conveniently downsized the defendant’s crimes. This is to cushion the impact upon the CCP-state – the mother ship of corruption in China – by obscuring the full extent of official looting.

The Ministry of Railways (MOR) was long a hive of corrupt activity. No fewer than 15 senior officials have been dismissed for corruption since 2010. Liu’s sidekick Zhang Shuguang, the ministry’s former deputy chief engineer, was arrested at the same time and accused of ferreting away a mindboggling $2.8 billion into his overseas bank account. The stealing of such vast sums also shows how the budgets of state departments such as the railways, inflated by huge injections of stimulus after 2008, provided rich pickings for corrupt officials and the capitalist interests with which they are connected.

According to an investigation by the National Audit Office in 2011, five billion yuan was stolen from the budget of the flagship Beijing-Shanghai high-speed rail line, through fake receipts, illegal tendering and lax financial management. Similar massive corruption applies throughout the system. In some cases construction of new railway projects has started before the tendering process has been formally concluded. The widespread practise of subcontracting has been manipulated for maximum profit, with some contracts sold over and over again, each time for a profit until the process is exhausted. At the bottom of this subcontracting spiral are uninsured low-paid migrant workers who toil long hours with little or no training.

Wang Mengshu, who was deputy chief of the committee of investigation into the Wenzhou rail crash (in July 2011), explained how middlemen expected a payoff of between one and six percent of every deal. “If a project is 4.5 billion [yuan], the middleman is taking home 200 million,” he told the New Yorker. “And, of course, nobody says a word.”

Liu gained the nickname “Great Leap Liu” based on the frenetic expansion of the high-speed rail system under his command. But he also reportedly took a personal cut from every business contract the MOR awarded. He fostered a culture of ‘crony capitalism’ through links to private contractors like Shaanxi businesswoman Ding Shumiao, who Liu helped to win railway contracts worth 3 billion yuan (US$490m). Ding is reported to have arranged for Liu to have sex with young women including some cast members of the television show Dream of the Red Chamber, which her company invested in. Hong Kong newspaper Ming Pao reported that Liu had eighteen mistresses. The media focus in corruption cases is often on “immoral sexual relations” at the expense of a more penetrating investigation of economic crimes. Ding also seems to have acted as Liu’s private ‘treasurer’ dispensing huge bribes on his behalf.

“Fake trial”

“It was a fake trial as usual,” declared human rights lawyer Pu Zhiqiang, who predicted the court’s verdict will be “based on the will of the leaders but not the law”. The trials of top officials are scripted affairs, engineered to limit the political risks to the ruling CCP as far as possible. In China’s byzantine political system, corruption investigations often represent tactical stratagems in the CCP’s internal power struggle. Authoritative reports suggest Liu Zhijun was, with Ding Shumiao’s help, trying to bribe his way into the top leadership, even the politburo. “He told Ding Shumiao, ‘Set aside four hundred million [yuan] for me. I’m going to need to spread some money around,’” Wang Mengshu, the investigator, told the New Yorker (22 October 2012). “The central government was worried that if he really succeeded in giving out four hundred million in bribes he would essentially have bought a government position. That’s why he was arrested.”

According to media reports in Singapore, Liu even set his sights on a vice premiership, planning to spend 2 billion yuan (US$320 million) to win ‘election’.

Liu was brought down by former leaders Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao in February 2011, in a pre-emptive strike by then president Hu’s faction (Youth League) against the faction of his predecessor Jiang Zemin (Shanghai Gang), with which Liu is connected. Liu is said to have regularly accompanied Jiang on his train journeys within China. China’s intra-governmental struggle – sometimes described as “one party, two factions” – intensified with the battle for top-level positions ahead of last year’s 18th CCP Congress. The dismissal and detention of former Chongqing party boss Bo Xilai, another Jiang acolyte, in March 2012, saw the struggle erupt in a rare public split.

Hu and Wen nipped Liu’s grab for power in the bud with the aim of weakening the Jiang faction. But they also had their sights set on breaking up the MOR, often described as the “last bastion of planned economy” because of its powerful position within the national economy. This political agenda of Hu and Wen – for the dissolution of the old ministry and partial liberalisation of the railway sector – has since been completed by their successors Xi Jinping and Li Keqiang. The leadership exploited the corruption scandals and crisis stigma attached to the MOR by the media, in order to neutralise resistance to this neo-liberal makeover, both from within government and from the general public concerned about potential fare increases and cuts to less profitable services.

The battle lines between party factions are not ideological or clearly political (all sides stand for capitalist development), but Jiang’s faction represents the princelings from elite CCP families, while Hu’s faction rests upon ‘low born’ officials who want to limit the princelings’ power within the economy and state machine, fearing the latter’s arrogant and unrestrained kleptomania will sooner or later trigger mass unrest against the regime.

Through the removal of Bo Xilai, Hu’s allies had hoped to gain the upper hand in the battle for positions in the new leadership. But the princelings hit back with threats in the form of well-placed and deeply damaging media leaks. One implicated Wen Jiabao in corruption (The New York Times reported Wen’s family had amassed US$2.7 billion). Another implicated Hu’s camp in an elaborate cover up of a fatal Ferrari crash involving the son of Ling Jihua, a close aide of Hu. The leaking of these scandals served as warnings from Jiang’s camp of a full-blown factional war unless the scale of the anti-Bo purge was limited, a scenario that risked ‘mutually assured destruction’ for all wings of the CCP regime. Xi Jinping meanwhile leveraged his position as an independent actor between the two main factions, while also a leading princeling, to broker a shaky peace and at the same time press his own terms for the new-look leadership.

Domino in a bigger game

Liu Zhijun is therefore just a domino in a much bigger game. Xi Jinping, the new supreme leader, is balancing between the two factions, tilting this way and that, to consolidate his own position and to contain factional infighting. With no sentence yet announced, it seems Liu will receive ‘leniency’ from the court – something that even the prosecution called for at the trial. This irregular intervention, even by the standards of China’s stage-managed trials, has outraged netizens. A post on Sina Weibo mocking the prosecutor’s call for leniency was re-tweeted 120,000 times in one day.

Leniency in Liu’s case would mean escaping the death penalty, following a similar pattern at the trials of Gu Kailai and Wang Lijun. Such an outcome would be a conciliatory gesture by Xi to the Jiang camp, for which some form of trade-off will be made. Some are speculating about a link to the fate of Bo Xilai, who seems to have disappeared into the darkest recesses of the CCP’s internal ‘shuanggui’ disciplinary system (Bo’s whereabouts are a state secret).

Rumours have it that Bo, who has yet to be formally charged, is refusing to cooperate with prosecutors. As a senior princeling Bo still has powerful defenders within the CCP-state and also enjoys support from ‘left-wing’ nationalists outside the government. Behind the scenes, Bo’s princeling supporters seem to be upping the pressure upon Xi to lessen his punishment. It is unclear at this stage whether Xi and the new leadership are merely treading carefully to avoid renewed factional warfare, or whether the manoeuvring over Bo is linked to a possible new strike against another top figure in the Jiang camp.

There is a possible connection to the fate of former security czar and politburo standing committee member Zhou Yongkang, who was allowed to retire quietly last year but is believed to be implicated in Bo’s shenanigans such as phone-tapping of other CCP leaders, including Hu Jintao. The recently announced investigation into Guo Yongxiang, the former vice governor of Sichuan province, could signal the beginnings of a move against Zhou. Guo, a close ally of Zhou’s, is suspected of unspecified “serious disciplinary violations” – a euphemism for corruption. “There’s a reasonably high likelihood that this has to do with a vendetta against Zhou Yongkang,” said veteran China watcher Willy Lam. Any attack on Zhou would in all likelihood be linked to a wider economic ‘reform’ agenda along similar lines to the MOR break-up, only in this case with the state-owned oil giants in the crosshairs. Zhou, another princeling, exercises de facto control over the oil sector.

Without a modicum of compliance, as shown by Liu, Gu and Wang, who all duly confessed to edited accounts of their misdeeds, the authorities cannot bring Bo into an open courtroom. “They won’t dare open the trial if there is any disobedience,” said law professor and long-time Bo critic He Weifang.

But a secret trial would be widely called into question as a cover up, and would throw away the propaganda value of a public demolition of Bo’s reputation. It’s also possible therefore that Liu is being used as the ‘bait’ to coax Bo, or at least some of his powerful backers, to accept a deal opening the way for Bo’s case to go forward.

High-speed expansion

The break-up of the MOR, sanctioned by the National People’s Congress in March, had been in the pipeline for a long time but faced resistance from ‘vested interests’ particularly from the tops of state-owned industries. Economic liberals in the CCP regime see the ministry’s demise as a symbolic victory for their cause, hoping to use this as a launch pad for greater liberalisation of the economy. Yet there is no evidence to support the idea that liberalisation and more private investment in formerly closed state sectors will reduce corruption – on the railways or elsewhere. This can only be acheived by full democratic control and the eradication of profit-seeking opportunities through genuine public ownership – by socialist measures in other words, which are anathema to the CCP leaders.

The new leadership are said to be preparing a major package of neo-liberal reforms to be finalised at the CCP Central Committee’s third plenum later this year. Although Li Keqiang as premier is the senior official in charge of economic policy, Xi Jinping has himself assumed responsibility for launching this reform plan according to media reports, hoping to emulate the famous third plenum of 1978, which is credited as the springboard for Deng Xiaoping’s market reforms. The New York Times reports that Xi has appointed Liu He, a well-known pro-market economist, to prepare for the plenum. Liu has been described as “China’s Larry Summers” – a reference to the former US Treasury Secretary and chief economic advisor to Obama. These internal shifts reflect a deepening crisis of economic policy for the CCP regime, a realisation that the current debt-driven and investment-heavy model is unsustainable.

The former MOR, as the second most powerful government agency after the military, and with a budget almost a big, was a symbol of this older economic model. Commenting on the break-up of the ministry, Wang Yiming, head of a think-tank under the National Development and Reform Commission (former state planning agency) exclaimed, “It means the country removes the last ‘stronghold’ in the way of reforming the industry from planned economy to market economy.”

The vast resources of the MOR allowed China to create the world’s longest high-speed rail network in only five years. But despite the rhetoric of liberal economists this was a far cry from a ‘planned economy’ even on the bureaucratic lines that applied under Mao Zedong. This was instead an example of state capitalism, on a grand scale, with rail expansion skewed towards capitalist development – inflating real estate values and enriching regime cronies – rather than meeting society’s needs. Not only was there a complete lack of democratic checks and controls, but initial reports of the charges against Liu Zhijun accused him of consulting a fengshui master to decide the most suitable dates for starting new railway construction projects (although this charge too was airbrushed from the final court indictment).

At its current stage of economic development what China needs is a massive upgrading of the conventional rail network, alongside modernisation of the electrical power grid to reduce the need for huge coal convoys, which currently account for around one-third of all rail traffic. This would deliver far greater economic and societal benefits than the regime’s bombastic and one-sided emphasis on high-speed lines that serve only an affluent minority – giving rise to the nickname “white-collar railway”. As we have seen, this multi-billion yuan programme has been plundered by corrupt contractors, overcharging for supplies and sending projects way over budget. The Beijing-Tianjin high-speed railway overshot its budget by 67 percent for example. A station in Guangzhou that was planned at a cost of 1.9 billion yuan (US$316 million) actually cost seven times as much. Liao Ran of anti-graft watchdog Transparency International, told the International Herald Tribune that China’s high-speed rail network was set to be, “the biggest single financial scandal not just in China, but perhaps in the world.”

The manic pace of rail expansion has also raised widespread safety concerns over ‘tofu dreg’ construction and ‘design flaws’ – the latter specifically named in the official report into the 2011 Wenzhou disaster in which two bullet trains collided, killing 40 people and injuring 200. The report gave Liu, already by then in detention, the “main leadership responsibility for the accident” (although this too was conveniently omitted from the charge sheet at his trial). Journalists investigating the use of substandard materials in high-speed rail projects have received threats, and official censors have ordered the media to kill reports on this subject. Yet the practice of substituting cheaper materials for good quality ones is rampant in the railway construction business, giving rise to its own phrase touliang huanzhu – “robbing the beams to put in the pillars”.

Safety concerns have further inflated the costs of the high-speed rail network, on which top speeds were cut by 50km per hour in the aftermath of the Wenzhou disaster. As Caixin reports: “The [Beijing-Shanghai] line requires four hours of maintenance every night when the train service is off. Every morning, two trains without passengers make a trial run on the line, one each from Beijing and Shanghai. Every ten days, the bullet trains and rail line will receive a safety overhaul.”

A problem that has proved harder to hide than safety lapses is the mountain of debt accumulated by the rail ministry, which quadrupled between 2008 and 2012. This was entirely predictable. “In China, we will have a debt crisis – a high-speed rail debt crisis,” says Zhao Jian, a Beijing-based professor and long time critic of the programme. “I think it is more serious than [the US] subprime mortgage crisis. You can always leave a house or use it. The rail system is there. It’s a burden. You must operate the rail system, and when you operate it, the cost is very high,” he told the Washington Post in April 2011. By the third quarter of 2012, the MOR owed creditors 2.7 trillion yuan (US$434 billion), a sum approaching the national debt of Greece (US$490 billion).

The debt crisis became a major argument for liberal forces pushing for the dismantling of the railway ministry, although in percentage terms its debt is below the average for China’s state-owned enterprises (SOEs), an indication of the severity of the debt crisis throughout the Chinese economy.

Xi’s crackdown on corruption

The break up of the MOR (its separation into two entities, one administrative and the other commercial), and incarceration of Liu Zhijun, represent early propaganda victories for Xi Jinping as an economic reformer and ‘graft buster’. Upon ascending the top post, Xi launched a populist anti-corruption campaign promising to bring down both ‘flies’ and ‘tigers’, meaning that senior officials would not be spared. Rather than introducing any democratic accountability into the system of government, Xi says, “power should be restricted by the cage of regulations” – a blueprint for a more professional, less corrupt, dictatorship.

This generated initial hopes within the liberal community – always too impressed by appearances as opposed to real substance – that Xi would embark on a policy of ‘political reform’ (partial democratisation). Such unreasoning trust in the new government, to use an expression of Lenin’s, is beginning to evaporate as reality sinks in. In fact, liberal voices are now becoming increasingly alarmed by Xi’s defence of Mao’s legacy, which mimics some of Bo Xilai’s pseudo-Maoist populism (which was also devoid of an anti-capitalist economic agenda). Xi’s tributes to Mao are only another example of CCP leaders “signalling left and turning right” – using Mao to silence calls for political reform while advancing a right-wing capitalist economic agenda. Similarly, Xi’s anti-corruption policies are designed to forestall and counter calls for democratisation, rather than facilitate them.

Like his predecessors Xi plans to wield the anti-corruption axe cautiously and selectively. The main difference is a more sophisticated populist media campaign to promote Xi’s measures, which are still however quite limited. These include a ban on public displays of official extravagance including lavish banquets that CCP officials and their business acquaintances have become accustomed to, and more stringent audits of spending by government departments and the military. A ban on the use of military vehicle number plates by family members, has rankled among PLA officers, but is far short of a serious crackdown on graft. Given the monumental scale of state corruption, these steps amount to no more than cosmetic changes, although skilfully promoted by Xi’s propaganda hands.

As US diplomat Winston Lord commented, “We will continue to see a concerted drive against Rolexes, Mercedes, shark’s fin soup and mistresses, a bevy of attacks on minnows and tuna, and a few against symbolic whales. What we will not see… is wrestling with the core problem.”

According to a report by Global Financial Integrity in October 2012, the Chinese economy suffered an outflow of US$3.79 trillion in illicit financial flows from 2000-2011. “In the past five years alone, over six hundred thousand [CCP] officials have been investigated for corruption-related activities,” noted Elizabeth Economy of the US Council for Foreign Relations. She added that, “the number that should be investigated is probably closer to six million or even sixty million.” [Council of Foreign Relations, 10 December 2012]

The proportion of corrupt officials placed under investigation is only a fraction, and those charged with criminal offences is smaller still. As Hong Kong’s South China Morning Post commented, “The chance of a corrupt official being imprisoned is just three percent, making fraud a low-risk, high return activity.” After more than two decades of turbo-charged capitalist development and five years of stimulus-frenzy, today’s CCP-state is steeped in corruption from head to foot. There are eerie parallels with the diseased Kuomintang regime, of which US President Harry Truman once exclaimed: “They’re thieves, every damn one of them.” Indeed, in their quest to contain corruption the current leaders have delved even deeper into China’s past. As Xinhua reported the ruling politburo invited two historians to attend its fifth group study session and outline how the feudal dynasties dealt with corruption and promoted clean and honest administration. This news prompted derision from netizens. Liberal commentator Zhang Lifan said this showed Xi’s administration aimed to establish a “party monarchy”.

“Play secretly…”

Therefore, while Xi can extract political capital from some early anti-corruption trophies (such as the trials of Liu Zhijun and possibly Bo Xilai, although both were downed by Xi’s predecessors), he also wants to avoid a wider crackdown, which risks aggravating factional conflicts and exposing too much of the CCP-state’s dirty linen.

As Harvard scholar Roderick MacFarquhar explains, Xi “cannot have a thorough-going anti-corruption drive that could target his senior colleagues and their cronies. A few egregious cases that become public may have to be prosecuted… I am sure Xi is serious but he cannot attack the elite and maintain tight control. They will get rid of him or he will have to become a military dictator…”

In other words, anything other than a limited, symbolic clampdown could split the CCP and endanger the survival of the regime.

At the same time, Xi has moved to rein in activists calling for tougher anti-corruption measures. In May and June more than a dozen activists were arrested for staging protests in Beijing and Jiangxi with banners demanding that officials declare their assets. Xi’s administration has also tightened controls on social media, to prevent a too rigorous exposure of corruption online. Many CCP officials fume over the “Trial by Weibo” phenomenon (China’s popular microblogging site) and demand protection. As for Xi’s crackdown on luxury, Xinhua reported a new catchphrase popular within the officialdom: “Eat quietly, take gently and play secretly”.

This is why many comment ironically after Liu Zhijun’s trial that he is the first high-ranking CCP official to “publicly declare his assets”.