For independent action by workers and poor

Robert Bechert, CWI

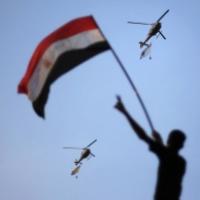

The removal and arrest of President Morsi by the military marks a new, challenging but potentially dangerous stage in the unfolding Egyptian revolution.

Morsi’s end came quickly against a background of a rapid mobilisation involving movement up to 17 million (about 20% of Egypt’s population) in mass protests. (see article “Huge protests demand the fall of Morsi”)

The scale, power and speed of this movement were stunning. It was an illustration of something often seen in revolutions; after the initial period of euphoria and hope, there are often renewed mass movements of those disappointed with what appears to be the revolution’s meagre results.

Egypt has seen a rapid fall in Morsi’s support which was, in the first place, limited. In the first round of last year’s presidential election Morsi won just under 5.7 million votes, about 11% of Egypt’s nearly 51 million electorate. Morsi’s 13.2 million second round votes were largely based upon the desire to stop his rival, the former air force commander and Mubarak minister Shafiq.

Increasingly Morsi and his Muslim Brotherhood government faced opposition from many sources. The failure of the revolution so far to deliver concrete economic and social improvements and the growing economic crisis fuelled increasing strikes and protests. Morsi’s November 2012 failed “constitutional coup” attempt to give himself extra powers was for many a key event, as was his outspoken support for the police after more than 40 people died in gun battles with the security forces in Port Said last January.

The Muslim Brotherhood’s attempt at domination also produced increasing opposition from more secular and Christian elements and also their Islamic religious rivals like the, Sunni fundamentalist, Nour party, which joined the protests at the end of June.

In a way, we have seen two separate struggles against Morsi. On the one hand, there is a mass, popular movement and, on the other hand, the remnants of Mubarak’s “deep state”, especially the military tops who have their own economic and political interests, who are trying to exploit the mass opposition for their own advantage.

Revolutionary potential and counter-revolutionary dangers

These two elements illustrate both the potential and dangers facing the Egyptian revolution.

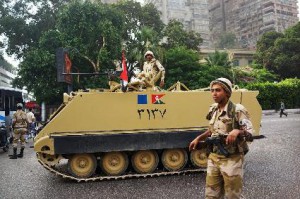

The speed and breadth of the movement shows the revolution’s tremendous energy and potential. But in absence of the development of an independent workers’ movement able to fight for a socialist alternative, the military tops, assisted by a selection of pro-capitalist politicians, have been able to seize advantage of the situation. Clearly the generals were afraid that the situation could, from their class point of view, get “out of hand”; there are reports of workers starting to go on strike on July 3 and that more planned to launch anti-Morsi strikes on July 4; something that could have led to the working class taking the initiative through mass, even general, strike action. Clearly the generals moved now in an attempt to seize the initiative and prevent a popular uprising removing Morsi.

The military leaders have acted to defend both their own personal interests and those of a section of the Egyptian ruling class. At the same time, they enjoy the tacit support of the main imperialist powers and also the Israeli ruling class. There has only been very soft criticism by Obama and other imperialist leaders of the generals’ coup, with general wishes for democracy. Given their past record the Egyptian military and security leaders can scarcely claim to be “democrats”. But this does not automatically worry Obama and co. as they quite happy live with authoritarian regimes in Saudi Arabia, UAE, Qatar etc.

This de facto military coup has allowed Morsi to pose as a defender of democracy and claim that the opposition to him was co-ordinated by “the deep state and remnants of the old regime” who paid hired thugs with “money from corruption” to attack the Muslim Brotherhood and “pull back old regime into power.” No doubt elements of the old Mubarak regime are involved in the movement against Morsi, but the protests’ mass base stems from opposition to and disappointment with the Muslim Brotherhood. At the same time undoubtedly sections of those presently supporting Morsi are doing so because of their opposition to the military, especially because of their memories of the old Mubarak regime’s sometimes brutal repression of all opposition including the Muslim Brotherhood.

In this situation it is absolutely essential that efforts are redoubled to build an independent workers’ movement, not just trade unions, which can offer a real alternative and appeal to those workers and poor backing Morsi because of their own opposition to the military and the old elite. This is the only way the workers’ movement can try to limit the ability of reactionary fundamentalist religious groupings presenting themselves as the main opponents to military rule.

The importance of this is shown in the continuing danger of sectarian divisions deepening between Sunni, Christian, Shia and more secular elements. Already some commentators are warning that the Muslim Brotherhood may be pushed aside by more fundamentalist, jihadist groupings in a struggle against the secularist, pro-western military. While the situation is different, it should not be forgotten that the Algerian military’s January 1992 cancellation of elections to prevent the victory of the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) led to an eight year civil war, estimated to have cost between 44,000 and 200,000 lives, which has held back the development of mass struggles in Algeria.

Workers cannot support this coup

There can be no support by socialists for this coup. The growing working class movement needs to keep its independence from both the military and Morsi. The involvement of so-called “liberal” or “left” opposition forces, like the Tamarod (Rebel) grouping, with the military will backfire on them. They will be seen as collaborators, especially if the military uses repressive and authoritarian methods against its opponents or future workers’ movements and strikes. Workers’ leaders must have nothing to do with either military backed or pro-capitalist governments. If they do not then it is possible that the Muslim Brotherhood, or other similar forces, may attempt to seize the leadership of future anti-austerity and anti-repression struggles.

Already the military are showing how they want to run things. First they set up the power structures, dominated by pro-capitalist elements, and then they will allow the people to vote. The generals have appointed a new president and they plan to install a “strong and competent” civilian technocratic government, alongside a committee to revise the Constitution, while the Supreme Court will pass a draft law on parliamentary election and prepare for parliamentary and presidential polls.

It is reported that many anti-Morsi protestors feel “empowered” after his removal, but while the huge mood swing against Morsi and the mass demonstrations are tremendously significant they do not, in and of themselves, mean “empowerment”. That is a concrete question of organisation and who holds the state power. Currently in Egypt it is the generals who are trying to consolidate their own power on the backs of the mass movement.

Inevitably in this crisis economy the new government will come under pressure from the IMF and others to begin so-called “reforms” which will probably include cuts to subsidies and other austerity measures. This will lay the basis for class struggles when the military and its government attempt to go onto the offensive, possibly using increasing authoritarian and brutal measures to try to impose their will.

This is why it is so important that the popular movement organises itself to fight for its own demands and against the installation of a military backed regime.

Working class must build its own alternative

Two and a half years ago on the day when Mubarak resigned the CWI circulated a leaflet in Cairo arguing for “No trust in the military chiefs! For a government of the representatives of workers, small farmers and the poor!” (“Mubarak goes – clear out the entire regime!”, February 11, 2011)

Its demands are still valid today. We argued that:

“the mass of the Egyptian people must assert their right to decide the country’s future. No trust should be put in figures from the regime or their imperialist masters to run the country or run elections. There must be immediate, fully free elections, safeguarded by mass committees of the workers and poor, to a revolutionary constituent assembly that can decide the country’s future.

“Now the steps already taken to form local committees and genuine independent workers’ organisations should be speeded up, spread wider and linked up. A clear call for the formation of democratically elected and run committees in all workplaces, communities and amongst the military rank and file would get a wide response.

“These bodies should co-ordinate removal of the old regime, and maintain order and supplies and, most importantly, be the basis for a government of workers’ and poor representatives that would crush the remnants of the dictatorship, defend democratic rights and start to meet the economic and social needs of the mass of Egyptians.”

Since then there has been a tremendous development of the Egyptian workers’ movement in terms of trade unions, committees and the experience of action. This provides a basis for creating the kind of mass movement that is needed.

In February 2011 we wrote that the Egyptian revolution can be “a huge example to workers and the oppressed around the world that determined mass action can defeat governments and rulers no matter how strong they appear to be.”

This is as true today. The renewed mass movement in Egypt can inspire those who see revolutions not resulting in real change as in Tunisia, the descent into a largely sectarian civil war in Syria and the continuing repression in Saudi Arabia, UAE etc. But while the recent days in Egypt have shown the potential power of mass action, they also show again the need for the workers’ movement to have a clear socialist programme and plan of action, otherwise other forces can try to divert, and ultimately defeat, the revolution.