Politically explosive investigation of former security czar marks a new phase of internal power struggle

Vincent Kolo, chinaworker.info

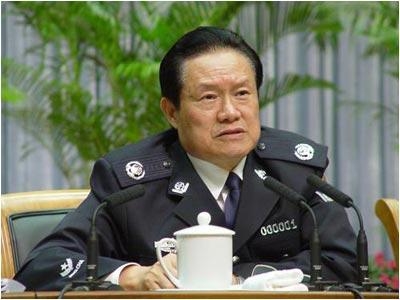

According to international media reports, including articles by Reuters and The New York Times, former Politburo Standing Committee member Zhou Yongkang and members of his immediate family and household staff are now under formal investigation for corruption and other crimes. A top-level decision has been taken to place Zhou and his wife under house arrest. This follows months of rumours and speculation of an anti-corruption swoop against Zhou, who from 2007 to 2012 was the third-ranked official in the ‘Communist’ Party (CCP) hierarchy. As head of the Political and Legislative Affairs Committee (PLAC) he controlled China’s feared internal security apparatus. Under Zhou’s stewardship the budget for internal security (courts, prisons, investigators and police) swelled from 406 billion yuan in 2008 to 702 billion yuan (US$116 billion) in 2012 – matching Vietnam’s GDP.

Overseas media reports based on ‘insider’ sources say the current Politburo Standing Committee headed by Xi Jinping decided in early December to initiate a formal criminal investigation of Zhou. This follows the detention and investigation of several top executives and former executives of CNPC, the oil giant, and former leaders of Sichuan’s provincial party administration, all closely connected to Zhou, with investigators applying a strategy described by the Chinese media as “pulling the tiger’s teeth before stabbing its heart.” The case against Zhou has likely been built on confessions from these sources, perhaps in exchange for offers of leniency. This includes Zhou’s eldest son, Zhou Bin, who according to some reports has been detained by investigators for several months.

The allegations in overseas media not only link Zhou and his family to massive corruption, but also to various criminal acts including ordering the murder of his ex-wife, links to organised crime and extra-judicial killings, and plotting to overthrow the current CCP leadership of Xi Jinping. These reports paint a picture of intrigue and skulduggery that far overshadows even the sensational revelations from the case against Bo Xilai, a close ally of Zhou’s, who is serving a life sentence following a heavily manipulated semi-open trial earlier this year. The Zhou family’s corruption is believed to run to billions of US dollars. So grotesque are the crimes mentioned that the CCP leadership faces a huge dilemma in pursuing its case against Zhou, which threatens to drag the entire regime deeper into the swamp of political scandal.

High-level corruption cases in China are not really about corruption, which is endemic throughout the state, but are a tool in internal political struggles. Xi Jinping is using a high profile anti-corruption campaign, pledging to bring down ‘tigers and flies’ (high and low-level officials), in order to rebuild the regime’s badly eroded public support while also striking blows against potential opponents within the ruling elite. Anti-corruption also provides a valuable cover for the regime’s planned restructuring of state-owned enterprises in the interests of private capital. Many commentators interpret the move against Zhou as a sign that Xi has successfully consolidated his personal control over the one-party state. Zhou has been compared to Stalin’s sinister secret police chief Lavrenti Beria and the prosecution of such a vile figure would undoubtedly be very popular among the broadest layers of the masses in China.

“It’s official”

While as yet there is no official announcement, The New York Times (15 December) quoted sources close to the Chinese leadership reporting Zhou’s house arrest. “It’s not like in the past few months, when [Zhou] was being secretly investigated and more softly restricted,” the newspaper quoted a lawyer with family connections to the party elite. “Now it’s official.”

This affair underlines the severity of the CCP’s internal crisis and dramatic shake-up that is underway, with far-reaching implications for the direction of the one-party state. Not since the Cultural Revolution has such a prominent leader or retired leader of the CCP been openly purged. If the case goes to trial it would also be a first since the establishment of the current state in 1949 – for a former Standing Committee member to face charges of murder and corruption.

It is impossible to get a full picture of the internal manoeuvres, but Zhou’s downfall appears to be the latest in a succession of moves by Xi Jinping to concentrate ever greater power in his own hands and send a warning to potential opponents. This in turn reflects the impasse of the CCP regime and its desperation to launch a programme of neo-liberal economic restructuring which it sees as the only way to avert a looming debt crisis and a slide into Japanese-style stagnation. This process is discussed more fully in our article China’s Third Plenum: More market, more dictatorship. Zhou’s case underlines the crisis of legitimacy facing the CCP regime as social tensions reach explosive levels. Xi could face enormous pressure to show, by capturing a ‘tiger’ like Zhou, that he is intent on serious ‘reform’. To act or not to act – both involve big risks for Xi Jinping.

By moving against Zhou, Xi appears ready to flout the unwritten rule that members and ex-members of the Standing Committee are untouchable. Among these leaders and ex-leaders are the heads of some of the most powerful and corrupt business clans in China. Regardless of how other elite figures viewed Zhou Yongkang, the fact that one of their own could be threatened will be deeply unsettling. This raises questions about the future course of the power struggle and possible reactions from the old guard. “Former [Politburo Standing Committee] members will be worried that China’s current leaders could come after them,” Professor Dali Yang of the University of Chicago told the BBC.

‘Oil faction’

Zhou Yongkang rose to power through the state-owned oil industry, to become CEO of China National Petroleum Corp (CNPC), the country’s largest oil and gas producer in the late 1990s. He is regarded as the leading figure in the so-called ‘oil faction’ that runs the state oil monopoly as its own industrial fiefdom, leveraging this control to extract fabulous personal wealth. The so-called ‘petro purge’ against several oil executives that began earlier this year indicated the noose was tightening around Zhou. According to The New York Times, quoting an unnamed former corruption investigator, “The Zhou family’s sway within the oil sector could offer many potential sources of illicit wealth, including acquiring rights to operate fields, service contracts, equipment sales and distribution of oil.”

The Hong Kong-based Apple Daily reported that Zhou’s son Zhou Bin skimmed off more than 10 billion yuan (US$1.6 billion) from public projects in the city of Chongqing alone. Overseas reports give differing accounts, saying that Zhou Bin fled last year to Singapore or Canada. He was reportedly brought back to China in September 2013 and according to the Daily Beast has agreed to cooperate with the investigation into his father in exchange for leniency.

An article in Caixin Magazine, a publication thought to have links to CCP anti-corruption czar Wang Qishan, has run a series of articles on well-connected families profiting from the oil industry. These articles mention the son, daughter-in-law and in-laws of Zhou Yongkang. As with the corruption-driven purges at the former Ministry of Railways from 2011 onwards, the regime’s strike against CNPC’s leadership may serve a double purpose, not only to build a case against Zhou but also to speed-up so called market reforms in the energy sector. This could pave the way for a bigger stake for private capital and even the break-up of CNPC into smaller, more ‘pliable’ companies, to tame one of the most visible ‘vested interests’ that has consistently obstructed the leadership’s wider neo-liberal market agenda.

A public trial of Zhou poses bigger risks even than the trial of Bo Xilai, which the state partly lost control over. While Zhou’s position contrasts sharply with perceptions of Bo Xilai, who enjoyed a significant level of public support, huge political risks are involved. A trial and publication of even a portion of Zhou’s alleged crimes could generate mass disgust against the entire power structure by revealing the degree of rottenness at its very core, with the man previously in charge of the the country’s police and law courts exposed as a master criminal.

As other recent corruption cases show (the trials of Bo Xilai and Liu Zhijun for example) the prosecution can be expected to ‘downsize’ specific charges of corruption in order to hide the full scale of official plundering and to protect other CCP officials and businessmen. If Zhou Yongkang is formally prosecuted, the case is likely to focus on economic crimes, rather than the allegations of plots to assassinate or overthrow other regime figures including Xi Jinping. Such allegations are likely to be too sensitive and damaging to the regime, exposing the severity of its internal disorders. But controlling such a process may be difficult if not impossible. Therefore, it remains to be seen how Xi and the CCP leadership pursue this case, and whether an attempt will be made to keep the affair behind closed doors. But clearly, the Zhou Yongkang affair opens a new chapter on the deepening internal crisis of the Chinese dictatorship.