Berlin Wall brought down by mass revolutionary movement

By Robert Bechert, CWI, who was living in Berlin in 1989

While, for millions, the 1989 opening of the Berlin Wall was rightly celebrated as a great victory for democratic rights, the official celebrations to mark its 25th anniversary have been dominated by anti-socialist propaganda. Governments have sought to hide the fact that, initially, the revolutionary movement that opened the Wall was pro-socialist and that it was only afterwards that hopes and illusions in capitalism came to dominate the protests in east Germany.

Of course no-one can escape the fact that it was a mass, revolutionary movement of the east German people that won the right to travel the world, if not necessarily the money to do so. But the official propaganda buries the initial revolutionary and pro-socialist character of the movement in autumn 1989 and makes it seem that, from the outset, the protesters’ aim was to bring back the capitalism via uniting with west Germany.

Thus the current German government’s central website simply claims that “Hundreds of thousands of peaceful demonstrators overcame the GDR dictatorship in 1989. They brought down the Wall and freed the way to German unity. Their courage for freedom was also courage for the future.”

Internationally, the November 9 anniversary of the Wall’s opening is being exploited by many capitalist governments to allow them to appear that they were always on the side of “democracy” and free travel. This is complete hypocrisy, the rulers of both capitalist and the former Stalinist states were always willing to support and ally with dictatorships if it was in their interests.

After West Germany joined NATO in 1955, the then Bonn government was happy to be allied with the Portuguese military dictatorship until it was overthrown by the 1974 revolution. As far as free travel is concerned, in many ways it is increasingly restricted to those with money. Internationally, visa restrictions are being continually tightened while the Berlin Wall has been replaced by new barriers east and south as the European Union has worked to construct a “Fortress Europe”. Meanwhile the US government has kept on strengthening its walls and barriers on its Mexican border.

But the monstrous border, with its killing zones, that the GDR (the German Democratic Republic), the then east German regime, maintained alienated millions and allowed the western powers to paint a horrible picture of a “socialist” country which used force to keep its population inside.

GDR: Not capitalist but not socialist

Initially there was some enthusiasm for the creation of the GDR. Partly this reflected the widespread support for socialist ideas throughout Germany immediately after the Second World War. The GDR was at first seen by a section as more “anti-fascist” and “progressive” than west Germany which was clearly capitalist and had a large number of ex-nazis in key positions in the economy and state. This popular support for the GDR meant that for some time it was possible to move between the two Germanies.

But the GDR, while not having a capitalist economy, was not a socialist democracy. Its regime was modelled on that of Stalin and run by an elite group of bureaucrats, something seen in the brutal crushing of the 1953 workers’ uprising and the continuing suppression of any serious criticism or dissent. This led to increasing numbers moving to the west and, in 1961, the regime building the Berlin Wall to complete the sealing off the inner-German border.

For some decades the GDR developed but then, like in other Stalinist states, top-down bureaucratic methods began to strangle the economy. Internationally this led to the crisis gripping many Stalinist states in the 1980s, especially in the then Soviet Union where Gorbachev’s attempts at reforms helped stimulate movements from below. This development had a big impact in the GDR and other countries. Increasingly in the late 1980s the changes in the Soviet Union, especially the greater toleration of open debate, were seen in other Stalinist states as an example to follow, something which the totalitarian GDR leadership tried to resist.

1989: Revolution kicks off

One of the sparks that led to the 1989 movement was the rigging of the local elections held in May that year. Protests began but also there were suddenly opportunities to leave the country as first Hungary, and later the then Czechoslovakia, opened their western borders. For those living in the GDR a crucial difference with other Stalinist states was that West Germany would immediately grant citizenship and full welfare benefits to any east German citizens who arrived there.

As increasing numbers left the GDR many started to discuss whether they should try to leave the country or whether they should try to change it. The majority decided to stay.

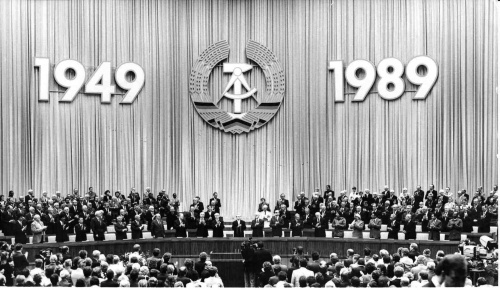

This was the background to the regular protests that first began in Leipzig on September 4 and rapidly gained strength particularly after clashes around the celebration of the GDR’s 40th anniversary at the beginning of October. Soon a tremendous momentum developed. Despite attempts at repression the protests kept expanding. As the authorities began to back down from using force the protestors grew in confidence. In 15 days, the numbers participating in the “Monday demos” in Leipzig jumped from 70,000 on October 9 to 250,000 on October 23.

Revolution’s initial pro-socialist colour

The largest single protest was the demonstration of up to a million people in east Berlin on November 4. This was a huge proportion of the GDR’s 16.1 million population. However this protest is downplayed in the official story, even though it played a key role in the events that led, five days later, to the opening of the Wall.

As the Berliner Zeitung recently commented “In the official revolutionary calendar November 4, 1989 has never really found its entry. 9 October is celebrated as the triumph of nonviolent resistance, November 9 for world historical reasons. And then there is also 3 October. But how is it that this day on Alexanderplatz has faded so quickly in the united German memory?” (November 4, 2014)

The fundamental reason for the official downgrading of November 4 is simple – its demands were not just for free elections, free media, the freedom to travel, to criticise but also for “democratic socialism”. Speaker after speaker spoke about this and there was no opposition. Typically, one of the rally’s first speakers, the actor Jan Josef Liefers, said that the old structures cannot be renewed, they must be destroyed, “We must develop new structures, for a democratic socialism. And for me that means changing the division of power between the majority and the minority”.

This was not accidental, opinion polls at that time showed majority support in the GDR for socialism in some form. The very first leaflet issued by “Demokratischer Aufbruch” (DA), the group that current German Chancellor Angela Merkel joined, called for “a Socialist society on a democratic basis”, despite the DA being the most right wing of the new groups and parties then emerging in the GDR.

Taken together these popular demands had much of the programme for a political revolution which Trotsky and his followers first advocated in the 1930s against Stalinist rule in the then Soviet Union. At that time in the GDR the small number of CWI supporters advocated concrete steps to achieve that socialist goal and which would have had great appeal to workers and youth in the other Stalinist countries and also in the capitalist west.

But now this “socialist” period of the movement has been buried and official history concentrates on November 9 and then jumps to the end of November and early December when east German support for a rapid unification with west Germany soared.

The reasons for this change in popular opinion in the GDR were various. There was no force that was proposing concrete steps that were needed to build “democratic socialism”. The opening of the border made many east Germans see the strength of west Germany and they questioned what future the GDR would have on its own. West Germany’s attraction was that then it was the world’s third strongest capitalist power and not a Portugal or Greece. In addition, joining west Germany was increasingly seen in the GDR as the quickest way to get rid of old GDR elite.

At that same time, West German leaders saw both a threat and an opportunity. In mid-October 1989 Schäuble, then interior and now German finance minister, told the Financial Times of the danger of “uncontrolled events” in East Berlin and a threat of the “destabilisation” of the GDR. But also the German capitalists saw the chance to reunite the country under their control as well as strengthening their international position by throwing off the last of the restraints imposed on them after the Second World War.

Events sped up as protests against the GDR leaders continued and more and more GDR citizens voted with their feet. Soon, tens of thousands were leaving the GDR for west Germany, by early November the rate was 9,000 a day.

On November 8, the first calls of “Germany, Fatherland” were heard on a 400,000 strong Leipzig demo. Soon, this call was getting more and more support and the West German leaders decided to seize the opportunity to campaign for unification. This won massive support in the March 1990 GDR election that paved the way for unification the following October.

In many ways this was, in effect, a takeover. The idea included in west Germany’s ‘Basic Law’ that, should Germany be united, there should be a discussion on a new constitution was dropped. The German capitalists feared that there would be demands for a new constitution to guarantee social rights, like jobs, housing etc.

Shock therapy and German welfare

Instead unification meant a German version of “shock therapy”: the rapid and brutal re-introduction of capitalism seen in many other former Stalinist states.

As the planned economy was dismantled, the former GDR’s industrial production dropped by two-thirds between 1989 and 1991. Industrial employment dropped from 3.2m to under 1m by mid-1992. There was an extremely rapid de-industrialisation of what was, before 1939, Germany’s industrial heart.

But the difference between the experience in east Germany and the other former Stalinist states was that the German ruling class pumped huge amounts of money into the area to buy social peace.

Between 1991 and 2013, the German government spent two trillion euros (£1.6 trillion) in the former GDR. Yet this did not prevent a savage de-population, the area’s population is down by 13.5% since 1990. Despite this population drop the latest unemployment figures show that eastern Germany’s jobless rate is almost double that of the west, 9% compared to 5.6%. Also today eastern Germany’s average pay is 25% lower than in western Germany. GDP per head is 30% below the west’s level.

The loss of jobs, the shock of the introduction of the market that ended guaranteed jobs and housing and, later the introduction of some cuts, resulted in different waves of protests in eastern Germany, especially in the early 1990s against job losses and in 2004/5 against the “Hartz IV” social cuts.

Continuing support for socialism

The experience of the last 25 years has not fundamentally weakened the general idea in east Germany that socialism is preferable to capitalism.

Recently the German weekly Die Zeit published the results of an opinion poll showing that, at different times during the last two decades, there was majority support for the idea of Socialism in both east and west Germany. This has been stronger in the east where, in 2010, 72.8% of east Germans felt that “Socialism is fundamentally a good idea, but was badly implemented”. This figure was only a slight fall from the 75.9% having that view in 1991, a year after unification. Three years later, after further experience of capitalist restoration 81.1% of east Germans had that view.

Over the same period, there was a sharp increase in support for Socialism in western Germany. It rose from 39.1% in 1991 to 45.8% in 2010, with the biggest rise being at the turn of the century, when in 2000, 52% west Germans were recorded as having that view.

These figures illustrate the potential support that a socialist movement to change society has in Germany. It is one of the reasons why Die LINKE (the Left Party) is strongest in today’s east Germany, although for this party, socialism is just a vague long-term goal that is occasionally mentioned. At this moment, Die LINKE is about to become head of a three-party coalition government in the eastern German state of Thüringen, the first time it has led a regional government. But this will not be a step towards building wider support for socialism as the LINKE leaders have made clear that they want to operate within capitalism.

However, this does not mean that the aspirations for a genuine socialist democracy are buried. The continuing turmoil in the capitalist economy will result in a questioning that will provide fertile soil for the ideas of socialism to grow and become the basis of a movement for change.