A short history of the Olympics: Rather than the Olympic movement’s self-professed ideals of ‘internationalism’ and ‘fair play’, the Games are about two at first sight contradictory forces: nationalistic flag-waving and capitalist globalisation

Vincent Kolo, chinaworker.info

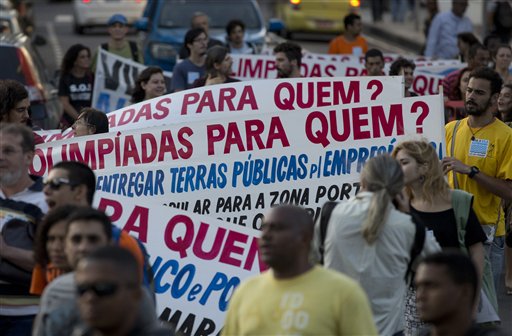

The Rio Olympics kicks off this week. The 2016 games, like their forerunners, will not only offer a great sporting competition but also generate controversy and protests against big business and political corruption, property speculators, massive debts, and an elitist structure that largely excludes the poor while enriching a tiny minority of media organisations, corporate sponsors and star athletes. This article was first published on chinaworker.info on 1 August 2008, on the eve of the Beijing Olympics, which ticked all the above boxes and a few more. These games were utilised to project the power of the Chinese dictatorship and generate nationalistic intolerance towards national minorities such as the Tibetans.

“Beijing win is big business,” ran a BBC headline in July 2001. China had just been awarded the 2008 Olympic Games. The Olympics is not just the world’s most prestigious sporting event; it is also one of the most successful marketing empires in the history of capitalism. The Olympic symbol – five connected rings representing the five continents – is one of the world’s most recognisable and closely guarded corporate logos. The small, secretive, unelected group that controls the Olympics, the 110-member International Olympic Committee (IOC), commands huge financial resources and is feted by governments and business leaders the world over. Former IOC president Juan Antonio Samaranch insisted on being addressed as ‘Your Excellency’. His megalomania earned him the nickname ‘Lord of the Rings’.

The Beijing Olympics is expected to bring in $2.5 billion from television broadcasting alone. This is set to rise to $3 billion for the period up to and including the London Olympics in 2012. The last time the Games were held in London, in 1948, the BBC reportedly agreed to pay just $3,000 to televise the event. But the British Olympic Committee never cashed the cheque, out of consideration for the BBC’s delicate financial situation!

All this was before the Olympics and other major sporting events became big business. The corporate makeover of the Olympics took place under Samaranch, who was IOC president from 1980-2001. The first Olympiad to be staged under Samaranch’s ultra-commercial regime were the 1984 Games in Los Angeles, and from this point onwards the pricetag for television broadcasting rights soared “faster, stronger, higher,” in the words of the official Olympic motto. The revenue from television rights in Beijing is almost ten times the $287 million paid in Los Angeles.

Unsurprisingly, with billions of dollars at stake, the IOC has acquired a reputation for corruption. A major scandal shook the Olympic movement in 1999 over the coming Winter Games in Salt Lake City. Several investigations, including one by the US Department of Justice, led to the expulsion of ten IOC members who had been “caught elbow-deep in the goody bag” according to The New York Times. They had accepted bribes ranging from real estate deals, paid holidays, plastic surgery and college tuition payments for their children. The scandal cost the mayor of Salt Lake City her job, but IOC boss Samaranch survived, narrowly.

This scandal prompted intense speculation about the future of the Olympics, the total lack of transparency and democratic accountability of its governing body, and its shady connections with big business. A debate raged over whether the IOC could ‘reform itself’ – echoing discussions over the future of China’s ruling ‘communist’ party (CCP). Corruption and vote-buying scandals however continue to shroud the Olympic movement long after the departure of Samaranch. In 2006, the Japanese city of Nagano was found to have provided millions of dollars in an “illegitimate and excessive level of hospitality” to IOC members. Nagano spent more than $4.4 million to entertain IOC members during the bidding process, which works out at $46,500 per head.

China’s government, the IOC, and its big business partners have a lot in common. They’re all undemocratic, elitist, and mostly corrupt organisations. The IOC, nicknamed ‘The Club’, is not an elected body – existing IOC members select new members, under a system not unlike that of the CCP’s ruling bodies. Hence, the notion that the Olympics, controlled by a dictatorial regime, could be an agent for democratic change in China is ludicrous. The IOC brooks no dissent. In the run up to the 1936 Berlin Games, hosted by the Nazi regime, Ernest Lee Jahncke, an American IOC representative, spoke out publicly for a boycott. This led to his expulsion from the IOC in 1935, the only expulsion in the organisation’s history until the Salt Lake City corruption scandal half a century later.

‘Rushi’ – ‘joining the world’

Hard-headed business calculations but also geo-political considerations lay behind the IOC’s decision in July 2001 to award the 2008 Games to Beijing. The corporate sponsors of the Olympics – including Coca Cola, Adidas and McDonald’s – were delirious over the opportunities this presented for ‘product positioning’ in a potential market of 1.3 billion people. A powerful multinational business lobby had thrown its weight behind Beijing, with US companies reportedly contributing two-thirds of the funds for the Chinese bid, which totalled $40 million. The Chinese regime had failed eight years earlier in its bid for the 2000 Olympics. That decision went to Sydney, with the relatively fresh memory of the 1989 Beijing massacre weighing against the Chinese bid.

In 2001, however, Samaranch was accused of “pulling strings behind the scenes to ensure that Beijing won the Games”. Admittedly, it was Canada’s IOC member who made this claim and he backed the other main candidate, Toronto. The Olympics would open “a new era for China,” said Samaranch. Henry Kissinger, who is an auxiliary (non-voting) member of the IOC, but also a key link between US capitalism and the Chinese leaders, called the Olympic decision: “a very important step in the evolution of China’s relation with the world. I think it will have a major impact in China, and on the whole, a positive impact, in the sense of giving them a high incentive for moderate conduct both internationally and domestically in the years ahead.”

The IOC decision coincided with the final negotiations for China’s accession to the World Trade Organisation (WTO), on tough terms that cost it more in market-opening concessions than any other ‘developing country’ member. The details of these negotiations and the concessions made by the Chinese side are still a ‘state secret’ inside China – journalists risk imprisonment for digging too deeply in this area. Joining the WTO meant the removal of “the last barriers between China and the forces of globalisation,” commented The Guardian’s veteran China correspondent, John Gittings. These two landmark decisions shared a similar strategic purpose – to tie China as a ‘stakeholder’ more firmly into the global capitalist system.

For China’s leaders, both decisions were seen as important pillars for the continuation of their increasingly neo-liberal ‘reform and opening’ policy. As C. Fred Bergsten points out in Foreign Affairs (July 2008): ”Beijing not only endured lengthy negotiations and an ever-expanding set of requirements in order to join the WTO but also used the pro-market rules of that institution to overcome resistance among die-hards inside China itself.”

This policy, including the privatisation and downsizing of former state-owned companies, and ‘marketisation’ of public services such as education and healthcare, was by this time running into increasing working class resistance. The news that Beijing would host the Olympics provided a welcome public distraction for the regime, helping to ‘sugar the pill’ of further neo-liberal globalisation. Huge celebrations were organised once the IOC’s decision became public, with possibly 200,000 – mostly from the middle classes – thronging Beijing’s Tiananmen Square. A wave of nationalistic pride mixed with expectation was thus engineered by the government on the theme that China was ‘rejoining the world’ – ‘rushi’ – and reclaiming its rightful place as an economic superpower. Beijing Olympic official, Wang Wei, called this “another milestone in China’s rising international status and a historical event in the great renaissance of the Chinese nation.”

As with almost everything the CCP regime does, its main focus is on the situation at home. As The Economist explained it is “more concerned with its own internal problems than with trying to influence faraway countries”. For an authoritarian ruling party struggling to keep control of a complex and fractious society and hold its own forces together, the Olympic Games are a powerful weapon – the equivalent of ‘nationalism on steroids’. The additional likelihood that China will displace the USA as top medal winner will be used to project an image of all-round economic and social progress under the stewardship of the current dictatorship.

Multinationals

The paradox of a nominally ‘communist’ regime that enjoys huge, almost sycophantic support from the world’s top business leaders is epitomised in these Olympics. A select group of twelve giant multinationals, which include Adidas, Coca Cola, Samsung and General Electric, have paid an average of $72 million each to the IOC to become so-called ‘top-tier’ sponsors of the Beijing Games.

For such companies Olympic sponsorship and advertising can play a decisive role. As the People’s Daily commented, “The Olympic Games is more than a sports arena, but also a battlefield for multinationals.” Kodak of the US used its sponsorship of the 1998 Nagano Winter Games as a lever to prize open the Japanese photographic film market, previously monopolised by Fuji. Visa International’s sponsorship of every Olympics since 1986 has helped it to displace American Express as the leading credit card company in the United States. Under Olympic rules, only one company from each corporate sector is accepted as a ‘top-tier’ sponsor. This explains why Pepsi Co. has always been shut out – Coca Cola has been associated with every Olympic Games since 1928. This exclusive arrangement extends to advertising and sales at all Olympic facilities, where Coke has a monopoly. Visa’s advertising campaign at the time of the Calgary Games read: ”At the 1988 Winter Olympics, they will honour speed, stamina and skill. But not American Express.”

This battle has shifted to Chinese soil, where it completely overshadows the Games themselves. “The global Olympic sponsors have huge budgets for marketing in China,” said a Hong Kong advertising chief. “When the torch relay is in China, every city which the torch passes through will be full of sponsorship logos,” he said. This is one important reason why the Chinese planners opted for the longest torch-relay in the history of the Olympics, covering 137,000 kilometres, or three and a half times the earth’s circumference. This ‘Journey of Harmony’, as the Chinese regime called it, turned into a heavily guarded farce, leading some Olympic spokespeople to conclude that the torch-relay may have passed its ‘sell-by’ date. Historically, before it became an advertising bonanza, the torch-relay began life in 1936 as a symbol of Nazi triumphalism. This ritual has nothing whatsoever to do with internationalism. On the contrary, it is a clue to the strong historical connection between the Olympic movement and fascist and authoritarian regimes.

“The idea of lighting the torch at the ancient Olympian site in Greece and then running it through different countries has much darker origins. It was invented in its modern form by the organisers of the 1936 Olympics in Berlin. And it was planned with immense care by the Nazi leadership to project the image of the Third Reich as a modern, economically dynamic state with growing international influence.” [BBC, 5 April 2008]

In China, the government has been whipping up ‘Olympic fever’ in an attempt to cut across rising discontent that poses an increasingly serious threat to its rule. Additionally, the regime hopes the Olympics will help trigger a consumer boom, to act as a ‘shock absorber’ for declining external demand as the global economy slows. China suffers from an abnormally low level of consumption – even Indians consume more as a share of gross domestic product (GDP). This is because wage levels have nowhere near kept pace with the overall growth of the economy. As a share of GDP, wages have fallen from 53 percent in 1998 to 41 percent in 2007, one of the sharpest declines in the world (and this during the period of preparation for the Beijing Games). In addition to massive sales campaigns by the multinational Olympic sponsors, more than 5,000 products have been dumped on the market with the Beijing Olympics logo. This includes apparel, mascot dolls, key-chains and even commemorative chopsticks. A number of these official Olympic products have been made at factories using child labour or violating other laws.

Every one of the ‘TOP’ (The Olympic Partner Programme) companies has a huge stake in China, and expects their Beijing Olympic investments to be rewarded with increased market share. Coca Cola dominates the Chinese soft drinks market and was the first American company to set up in China back in 1979, when Deng Xiaoping reopened the country to foreign business. Coca Cola has 30,000 employees in China, which is its fourth largest – and most profitable – market. General Electric, another ‘TOP’ company, is providing power and lighting systems for the Beijing Games. It also has an ownership stake in NBC Universal, which holds exclusive Olympic TV broadcasting rights in the United States, for which it paid nearly $900 million. GE’s sales in China grew fourfold in 2001-06.

Union-busters

Adidas, another long-term ‘TOP’ sponsor, saw its China sales grow by 45 percent in 2007, compared to five percent growth in Europe. Adidas aims for a sales turnover of one billion euros in China by 2010. The German sportswear giant also contracts most of its production from China, but here we are discussing an entirely different segment of the Chinese population. The low-paid migrant factory workers that make Adidas sneakers under inhuman conditions, might as well inhabit another planet to that thin layer of brand conscious middle-class Chinese shoppers that Adidas pitches its marketing towards.

Adidas sources more than half its global production from countries where trade unions are banned, principally China. The terrible conditions at the company’s Chinese subcontractors were highlighted in an article in The Sunday Times (UK), which reported from three “long-established partner factories” of Adidas in Fuzhou, southern China. Workers complained of forced overtime and wages below the legal minimum. They earned just 570 yuan ($83) per month in 2007 – barely enough to buy a pair of Adidas sneakers. This report also showed that China’s state-controlled trade union, the ACFTU, “was widely accused of doing nothing”. When workers staged a strike in 2006 they were all summarily dismissed.

Adidas is not exceptional. The ‘top-tier’ Olympic sponsors form a rogues gallery of union-busters. Electronics giant Samsung is another infamous example. The company has been fined in South Korea for a range of illegal activities involving blackmail and bribes to get trade union activists to quit. This most powerful of the country’s ‘chaebol’ conglomerates was for a long time a pillar of South Korea’s former military regime. An editorial in Hyankoreh said of Samsung: “In a democratic republic you have a world leader in advanced technology using primitive anti-union tactics from the development dictatorship years”.

Likewise, Coca Cola has been accused of union-busting activities in Colombia, Pakistan, Turkey, Guatemala and Nicaragua. A law suit was filed against the company by Colombian trade unions in 2001 on the grounds that Coke bottlers had “contracted with or otherwise directed paramilitary security forces that utilised extreme violence and murdered, tortured, unlawfully detained or otherwise silenced trade union leaders.” Coca Cola’s lobbying clout with Olympic officials was demonstrated when Atlanta, where the company is headquartered, got to hold the 1996 Olympics. This was just twelve years after another US city, Los Angeles, held the Games. Yet another top-tier Olympic sponsor, McDonald’s, is the archetypal union-busting company. An international seminar on labour practises at McDonald’s, organised by the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU) in 2002, concluded that: “McDonald’s tends to use minimum standards or minimum legal requirements in setting wages, health and safety practices, has a propensity to use anti-union measures including isolating, harassing and dismissing employees who are union members or supporters.”

“Sport, not politics”

In China too, McDonald’s was at the centre of a major scandal, when it was found to be paying young workers 40 percent below already low minimum wage rates. Several provincial governments were compelled by massive adverse publicity to investigate the fast-food giant. But while they confirmed that McDonald’s had violated China’s labour code in several areas, they refused to find it guilty of violating minimum wage rules. This affair (reported on chinaworker.info – China’s ‘McScandal’ shows the need for real trade unions, 22 May 2007) resulted in the puppet ACFTU negotiating its first ever union recognition deals with McDonald’s, but of course with management representatives appointed to lead its union branches. This is normal ACFTU practise. It is called, “trade unionism with Chinese characteristics”!

The anti-union, anti-working class bias of these Olympic sponsors conforms to a long tradition at the IOC of support for reactionary and anti-working class causes and regimes. To claim, as do the IOC, the sponsors and the Chinese regime, that the Olympics is only about sport, not politics, is utterly false and ignores the highly political history of the Games. The Chinese regime’s decision to route the torch-relay through the restive regions of Tibet and Xinjiang cannot be described as ‘non-political’. As the torch was whizzed through the Tibetan capital of Lhasa in June, with most Tibetans under curfew and unable to see it, Tibet’s Communist Party chief Zhang Qingli delivered a speech in which he called for opponents of the Olympic Games – and the CCP – to be “smashed”. An embarrassed IOC was compelled to deliver a rare rebuke to the Chinese government, reiterating that it must “separate sport and politics.”

In fact, most Olympiads have been surrounded by political controversy: Berlin 1936, Munich 1972, Mexico City 1968, Moscow 1980, Los Angeles 1984; the list is long. Just weeks before the Olympic Games opened in Mexico City, students occupied their universities demanding an end to one-party rule. This led to the ‘Tlatelolco Massacre’ in which dozens of young demonstrators were shot and killed by the military, determined to restore ‘order’ for the start of the Games. Once again, Olympic officials hid behind their “separate sport and politics” mantra: Mexico’s president Gustavo Díaz Ordaz, the blood barely dry on his hands, presided over the Olympic opening ceremony with the invited foreign dignitaries. Yet when the Afro-American athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos famously gave their black-gloved, anti-racist salute from the medals podium in Mexico City, they were expelled from the Games on the orders of the IOC president Avery Brundage.

The IOC and its supporters want it both ways. When they deal with dictators, they justify this with arguments that the Olympics can help to advance democracy and human rights. In other words, they claim an explicitly political rationale. But when this is shown to be untrue, as in China today, they reply that the Olympics is a sporting, not a political organisation. Jacques Rogge, the current IOC president, has made the absurd claim that the 1988 Seoul Olympics helped turn South Korea, then another dictatorship, into “a vibrant democracy”. According to Rogge, “The Games played a key role, again by the presence of media people.” [Financial Times, 26 April 2008]

In real life, the South Korean military regime was forced from power by a wave of mass strikes and demonstrations that erupted in June 1987 (a full year before the Olympics) and continued despite huge repression for the next three years. This is an important lesson for China, showing the decisive role of mass workers’ struggle in the battle against dictatorship. When it comes to the struggle for democratic rights, the Olympics is part of the problem rather than the solution. In a recent report, Amnesty International warns, “Hosting the Olympic Games has become a thinly veiled excuse to crackdown on freedom of expression and assembly.” [What human rights legacy for the Beijing Olympics? Amnesty International, 1 April 2008]

With an estimated 150 people killed by security forces in Tibetan areas, 2008 is already the worst year for state repression in China since 1989. Annihilating the arguments of the IOC and its apologists, Amnesty’s report states “much of the current wave of repression against activists and journalists is occurring not in spite of, but actually because of the Olympics.”

Neither is the Chinese state acting alone as it uses the Olympics to crack down on potential opposition. Interpol has agreed to cooperate with Chinese authorities, opening its database to “help China ensure that mischief-makers do not enter”. Ostensibly such measures are aimed at ‘terrorists’ from Xinjiang and Tibet (despite the lack of evidence that such terrorist threats exist). As prominent dissident Hu Jia commented: “The greatest threats aren’t necessarily terrorists or crime, the greatest threats are those who reveal China’s social problems and protest the government.”

The IOC has a tradition of racism, anti-communism and support for authoritarian regimes stretching back to its origins. That China’s leaders embrace this organisation speaks volumes about where they stand today. The founder of the modern Olympic movement in 1896 was the French aristocrat Pierre de Coubertin. His vision was not of a popular sporting movement for the masses, but one almost exclusively for the idle rich and the military officer caste. In the view of noblemen like de Coubertin, the ‘lower classes’ were unable to grasp the concept of ‘fair play’. Women, meanwhile, were deemed completely unsuited to the world of sport – a view that hardly changed until after the Second World War. Even at the London Olympics of 1948, women athletes were outnumbered ten to one by men. More Afro-American athletes actually competed in the 1936 Berlin Games than in Los Angeles four years earlier, due to institutionalised racism in the USA, which kept most sports segregated until the 1950s, and inspired the 1968 ‘silent protest’ by Smith and Carlos.

Baron de Coubertin was a ‘great French patriot’ who nevertheless became a staunch admirer of the Nazi regime in Germany. On his death in 1937, he bequeathed his lifetime literary collection to Hitler’s government. In a bizarre footnote, six months after his death, de Coubertin’s corpse was dug up in Lausanne, Switzerland, and his heart was cut out and transported to Olympia in Greece. There, it was reburied in a ceremony attended by his long-time friend, the Nazi official and organiser of the 1936 Berlin Games, Carl Diem.

Authoritarian tradition

The IOC awarded the 1936 Games to Berlin two years before Hitler came to power in January 1933. Rather than displaying regret, however, IOC leaders subsequently – and vehemently – defended the Nazis’ right to hold the Games. As news emerged of Nazi terror directed against trade unionists, communists, socialists and Jews, the call for a boycott of the Berlin Games grew, especially in the US, Britain, France, Sweden, Czechoslovakia and the Netherlands. A 1934 opinion poll showed that 42 percent of Americans supported an Olympic boycott. Facing a crisis, the US Olympic Committee sent its president, Avery Brundage, to Germany to assess if the Games could be held in accordance with ‘Olympic principles’. In reality, Brundage’s mission was a conscious manoeuvre to derail the boycott campaign, which Brundage blamed on “the Jews and the communists”. During his visit to Germany in September 1934, he met with Jewish athletes in the presence of three senior Nazi party leaders, one in full SS uniform with pistol. The Jewish athletes feared for their lives and dared not utter any criticism of the Nazi regime at this interview. Brundage returned to the US giving the Berlin Games his strong endorsement.

Brundage, who later became IOC president (1952-72), was also an admirer of Hitler and an open anti-semite. He cited Main Kampf as his “spiritual inspiration”. His friend, the leading Swedish capitalist Sigfrid Edström, who also later became IOC president (1946-52), was yet another fascist sympathiser. In 1934, as the boycott issue raged, Edström had written to Brundage: “The Nazi opposition to the influence of the Jews can only be understood if you live over in Germany. In some of the more important trades the Jews govern the majority and stop all others from coming in … Many of these Jews are of Polish or Russian origin with minds entirely different from the western mind. An alteration of these conditions is absolutely necessary if Germany should remain a ‘white’ nation.” [Letter from Edström to Brundage, 8 February 1934, from The National Archives of Sweden]

After the Berlin Olympics, Edström, then vice-president of the IOC, attended a Nazi party rally in Nuremberg and later declared: “It was one of the greatest shows I have ever seen … He [Hitler] is probably one of the most powerful and strongly supported individuals that the world’s history has ever known. 60 million people I am sure are willing to die for him and do whatever he requests.” Indicating that Berlin was no aberration, the IOC decided one year later to award the 1940 Olympics to Japan. That Olympiad never took place due to the war. The IOC’s decision to promote yet another militaristic and rabidly anti-communist regime, had been taken in the full knowledge of Japan’s atrocities in China, which its armies had occupied in 1931.

There was a sizeable layer of industrialists and capitalist politicians internationally who looked favourably upon Germany, Japan and other authoritarian or fascist regimes seeing them as bulwarks against the spread of ‘communism’. Only when the imperialist ambitions of Hitler and the Japanese Emperor clashed with their own, did the capitalist ‘democracies’ resort to ‘anti-Nazi’ rhetoric and eventually war. The parallel with China today, is that a large segment of the capitalists internationally see the current communist-in-name-only regime as their best hope to keep China ‘open’ for global capitalism and to hold down its huge, increasingly restive working class. This is why they enthusiastically support the Chinese dictatorship’s hosting of the Olympics.

After the Second World War, both Edström and Brundage used their IOC positions to try to secure the release of convicted Nazi war criminals. Most famously, they campaigned for the release from a Russian prison of Karl Ritter von Halt, who was Germany’s IOC member up until the end of the war, as well as a leading figure in Hitler’s regime. Ritter von Halt was released from prison in 1951 as part of the deal that saw the Soviet Union admitted to the Olympic movement for the first time.

Brundage continued to defend right-wing causes throughout his term as IOC president. He was a keen supporter of Senator McCarthy’s anti-communist witch-hunts in the 1950s and criticised president Eisenhower for halting the war in Korea, which Brundage called “a shameful act for all the whites in Asia”. The call for Brundage’s resignation as head of the Olympic movement was one of the demands raised by Tommy Smith and John Carlos in their 1968 protest (they also demanded that Muhammad Ali’s world heavyweight boxing title be restored).

In 1980, Juan Antonio Samaranch, arguably the most powerful of IOC presidents, took the helm. He described himself as “100 percent Francoist” – a reference to Spain’s fascist dictator. The official biography of Samaranch, published by the IOC, does not say a word about his long political career – that he was a fascist deputy in the Cortes and then Minister of Sport in Franco’s dictatorship. It was during this period that Samaranch developed strong contacts with Horst Dassler, heir to the Adidas empire, and a key behind-the-scenes figure in the Olympic movement. In the 1960s, Adidas’ distinctive black and white footballs were made by prisoners in Spanish jails, under a contract negotiated with the help of Samaranch. This use of forced prison labour was a prototype – on a much smaller scale – of today’s globalised sweatshop production chain.