Introduction to China Commission at CWI Summer School 2017 by Hayashi (CWI in China, Hong Kong and Taiwan)

There are a number of questions we need to discuss. How serious is the economic crisis in China? Is Xi Jinping really the strongest leader since Mao, as many claim? Where is the dictatorship’s foreign policy leading, such as its signature ‘Belt and Road’ economic plan? Is this set to gain even more strength or face setbacks?

State repression is getting worse and worse. Is our perspective that this would continue or will this change in the next period? Finally, what about the development of the workers’ movement and the tasks of a Marxist organisation in China?

Upturn in strikes

In 2016, there were 2,663 strikes in China, according to Hong Kong-based NGO China Labour Bulletin, which compiles these figures based on social media reports. It believes the real number to be up to eight times higher. Compared to 2014 the number has doubled and, for the first time, the combined numbers of strikes in transport, services and the retail sector is more than in manufacturing industry.

The Chinese government says the economy is transitioning from manufacturing to services, and growth of the service sector creates a lot of new jobs. But these jobs are even lower paid and with lower job security than manufacturing jobs, usually without contracts, so it is growth based on the informal sector.

Strikes in the transport and service sectors can get more attention compared to action by manufacturing workers because they more directly affect other workers’ daily life. For example, 5,000 bus drivers in Guangdong (southern province) went on strike in June and got a 40 percent wage increase, helped by the fact the whole city’s transport system was affected and the strikers gained a lot of public sympathy.

Also, companies in the service sector more and more use smartphones as a platform, like using phones to call a taxi or order takeaway food. These workers have no contracts or their contracts only exist on a phone app and can be changed at anytime. At the same time, this technology is also increasingly a platform used to link-up strikes.

Last year, takeaway food service workers went on strike in eastern China, protesting against unpaid wages. This action spread to a northwestern city. In 2016, the number of strikes in delivery services was three times higher than in 2015. The trend is more service sector strikes and more strikes spreading to other areas.

Extreme wealth gap

In manufacturing industry, unpaid wages and social insurance are the main cause of workers protests. In 2015, the number of migrant workers with unpaid wages was 2.77 million (1 percent), the total amount of unpaid wages was 27.2 billion yuan (US$4bn). Migrants are the majority of the labour force in construction and manufacturing.

China has the most dollar billionaires in the world, 594. In China’s fake parliament, the National People’s Congress (NPC), there are 100 billionaires. It’s the world’s richest parliament.

At the same time, workers’ average monthly salary is US$475. Around 280 million migrant workers have left their hometown and go to other cities in China to work. However, as factories have closed down due to the economic crisis, unemployment rates have increased and real wages stagnated. Especially the coastal cities are very expensive places to live, so many migrants can no longer afford to work there. Last year, the number leaving home to work in other cities decreased for the fifth consecutive year

This trend can make workers’ struggles more confident as workers can get greater support in their hometown. It is easier to unite and organise together because of fewer cultural and language barriers and stronger roots in the community.

Debt crisis

China’s debt crisis is “the biggest systemic threat to the global economy” according to Foreign Policy magazine.

The Institute of International Finance, a global banking body, puts China’s debt in 2017 at 304 percent of GDP. This is an extremely high level and the increase in the past decade, since the global capitalist crisis began, has been very rapid. Last year, the total debt of all emerging markets increased by US$3 trillion with China accounting for US$2 trillion of that increase.

In 2008, China launched a huge stimulus package to inject cheap credit into the economy. Many local governments and state-owned companies borrowed huge amount of cheap loans to expand investment. But this led to the accumulation of debt today.

Some capitalist commentators argue China will avoid a financial crisis despite this build up of debt because it is mostly internal debt. This is not like in the situation in Greece where the debts are owed to German and other foreign banks. In China the debt is mainly owed by local governments to the state-owned banks. However, the contradiction between different European countries over financial and economic policy can also happen in China between local governments and the centre.

The Chinese regime can order the state-owned banks to implement its policies. This is a bit like Japan’s economic crisis in 1990s (a slump was avoided by using the banks to prop up failing companies). This reality has allowed China to accumulate a much higher level of debt without a financial collapse. But this doesn’t mean that this situation can continue forever.

Xi Jinping wants to launch economic reforms to channel more private capital into the state-owned companies. His economic agenda is to allow more market competition, hoping to let some indebted small and medium-sized state-owned companies default. This is to reduce overcapacity and increase the efficiency of capital (reducing wasteful investments) and to clear the debt which is unsustainable. But if implemented this programme means a further slowdown of economic growth. This explains why Xi has in practise rolled back on economic reform, by injecting even more credit into the economy. The increase in credit of the past two years is greater than the 2008-9 stimulus package. In 2015, the regime was afraid the economy was slipping into recession, which because of the special contradictions of the Chinese economy could have triggered an even bigger financial crisis.

This has led to a situation where today China needs six dollars of debt to create one dollar of economic output (GDP), compared to one dollar of debt to one dollar of GDP in 2008. It also means that if the Chinese government uses the same stimulus measures to deal with the next economic crisis, the effect will be much less. So the government finds it harder and harder to soften the effects of crises.

Housing bubble

Over the past seven years, house prices have doubled in so-called 1st tier (richest cities). In 2nd tier cities they increased by 50 percent. Housing is absolutely unaffordable. In 1st tier cities like Beijing and Shanghai, for instance, the price for one square metre of property at average housing prices costs one year of average income. In cities like New York and Tokyo it would cost buyers a month of income.

The average price-to-income ratio for housing is 70 in Shenzhen, the most expensive city in China. In other words it costs 70 years of the average salary to buy the average apartment.

Speculators are increasingly investing in the housing sector because there are no other profitable sectors and the stock market is seen as too risky. An independent economist in China says, “Half of the total loans in China are exposed to the property sector, that’s even higher than Japan in 1989 when Japan’s asset price bubble burst in the early 1990s.”

This means that if China’s housing bubble bursts it will have a bigger effect on the banking system even than in Japan in 1990s. The son of an ex-Prime Minster admitted the huge problem of empty housing and gave a figure that 30 percent of housing in China is empty, enough for 300 million people to live.

The Chinese government claims they have a plan to clear the unsold housing inventory. But even if there is no more new housing, and the speed of sales stays the same as in 2016, it will take five years to clear all the inventory. However, construction has increased since early 2016 financed by more debt so this overcapacity is growing.

With China’s low household consumption rate (because of low wages, poor welfare, high savings and high housing prices), huge debts and deflation, in a long-term perspective the future for China is likely to follow the Japanese model of low growth or stagnation. If this happens in China it will cause a bigger political crisis because of the much bigger wealth gap and poorer social protection system compared to Japan.

Xi’s foreign policy

The Chinese regime’s foreign policy is linked to the internal situation and potential for political and economic crises. Xi needs to present himself as ‘strongman’ using nationalism to channel popular discontent away from his own policies.

But the Chinese economy has also outgrown its national market, a problem that becomes more acute given the international situation, with globalisation in reverse and the rise of protectionism. These processes are reflected in many contradictory ways in relations between the Xi and Trump governments, geopolitics, and China’s push for the ‘Belt and Road’ economic plan.

China at this moment has gained the upper hand over the US in the South China Sea conflict. Privately, US strategists accept they cannot reverse China’s militarisation of ‘islands’ it has built to secure its dominance in the dispute waters – that can only be achieved by war. More and more countries have in the past few years turned from the US bloc to China for trade and investment, including Malaysia, Thailand, and even traditional important US allies like the Philippines and Australia. This process has accelerated under Trump.

Trump faces a big crisis and pressure in the US and from Wall Street not to engage in a big confrontation with China. Now, at least temporarily, he seems to have backed down over launching an open currency war and trade war. But this may only be temporary, because of the many tensions that now exist between the two powers. China has exploited this situation at home and on the Asian and global stage to show Xi as a ‘strongman’ who can contain Trump.

OBOR

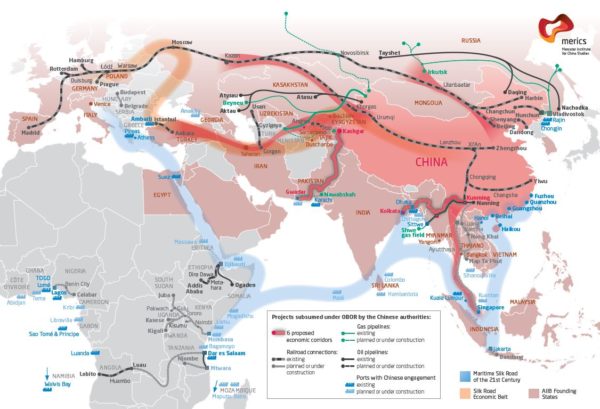

The Belt and Road initiative (also known as ‘OBOR’ – One Belt One Road) is Xi’s plan to link 65 countries, which make-up 55 percent of global GDP, 70 percent of the world population, and 75 percent of global energy supplies, into a China-led economic sphere.

OBOR is at least eight times bigger in financial terms than the post-1945 ‘Marshall Plan’ of US imperialism to rebuild and secure Europe against Stalin’s Soviet Union. This is “imperialism with Chinese characteristics” – it copies the state capitalist investment model from China to build infrastructure in the OBOR countries, also locking these governments into debt-dependency on China. China will issue loans to these countries through its new Asian Infrastructure and Investment Bank (AIIB) and other financial agencies it has set up, which are independent of the US-controlled IMF and World Bank, and enable it to export the debt burden from China to other countries.

Xi presents OBOR as “win-win cooperation” but it isn’t. It is Chinese economic and political domination. It will mean new winners and losers among the countries, social classes and national minorities covered by OBOR. Other problems will include wasted investments, increased corruption, state repression and environmental destruction.

OBOR countries include many that face military and security crises, terrorism and civil wars – countries like Pakistan, Afghanistan, Burma, and the Central Asian states. These factors can of course be an obstacle for China’s project. That’s why OBOR has a military component, with the Chinese regime considering deploying or employing military forces in these countries to protect its assets.

There are already rumblings of mass resistance over land grabs, pollution, corruption and national oppression in several of these countries, which can also be reflected in heightened anti-China and anti-Chinese nationalist moods. This points to political upheavals in the future – coups, electoral power struggles and mass movements – between pro- and anti-China wings of local ruling elites. Taken together with the economic risks of such a mega project, of uncontrollable debt, this can lead to ‘imperial overstretch’ which instead of saving the Chinese regime can trigger economic and political crisis in China.

Exporting debt

The Chinese regime needs to launch OBOR because of crippling levels of overcapacity at home – too much steel, cement, glass, etc. China has the world’s biggest construction and engineering companies that need overseas contracts because of the economic slowdown in China.

Sri Lanka is the first country to join OBOR. The island faces a debt crisis with total debts of US$64bn and around 95 percent of all government revenues going towards debt repayment. China built an unwanted international airport – just five flights take off every week – and seaport which is also a hardly-used white elephant. This port and the surrounding land area is now fully controlled by China for the next 99 years.

In Laos, China is building a high-speed railway at a cost of US$6bn in a country with GDP of US$12bn. Laos, one of Asia’s poorest countries, is just a transit link on China’s plan to build a high-speed railway from western China to Singapore. 100,000 Chinese workers are building the railway, all the materials are from China, and the technology is owned by China. For the masses in Laos the railway is bringing land grabs and repression against poor farmers and a massive debt.

State repression

One symbol of the political crackdown in China is the death of Liu Xiaobo, a right-wing liberal who was arrested in 2009 for writing a limited reform programme trying to persuade the Chinese dictatorship to undertake political reforms. He has been in prison since then and died of cancer in July. The regime refused to let him go abroad in his last days for medical treatment. Xi’s regime doesn’t mind a negative public image but wants to be seen as hardline and immovable.

More people are now being charged with the crime of ‘subversion’ of the regime. This includes NGO staff and human rights lawyers who have been arrested in recent crackdowns. LGBT public activities are banned.

The liberals in China do not stand for the overthrow of the authoritarian regime. They do not put radical proposals like free elections, political parties or trade unions, but only very modest prescriptions like fewer media and internet restrictions and less control over the judicial system. The labour NGO activists who are facing increasing repression only focus on legal advice and negotiations in workers’ struggle.

The power struggle

The regime’s 19th (“Communist Party”) Congress later this year will see a five-yearly change of leadership. Behind the scenes a sharp power struggle is being fought among the ruling elite.

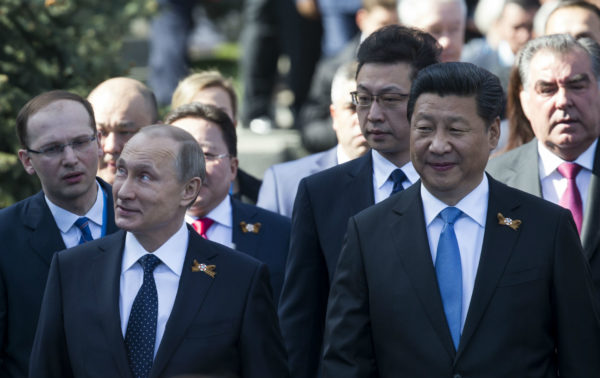

Xi has centralised power towards himself and broken from the past collective dictatorship model (sharing power among a few top leaders) to a one-man dictatorship model. Xi will stay in power for five more years but also wants to expand his power, promote his supporters and weaken all other factions. There is speculation he will try to change the rules to extend for the next ten years in power. His model is Putin in Russia.

The factional struggle within the regime is not at all about political ideas or programme. It is about protecting the interests of different factions, with their power based on their regions and sectors of the economy. Although Xi has the upper hand in this internal power struggle, it doesn’t mean his position is fully consolidated or is as powerful as many commentators say. There are signs that Xi is facing different levels of resistance from rival factions. A recent crackdown on the finance sector is partly because some private capitalists have gained too much power and become too independent of the regime and need to be brought back under control.

Xi has used the anti-corruption campaign for five years as a tool in the power struggle, to remove some opponents and warn rival factions not to oppose him. The anti-corruption campaign was never really about corruption because all the factions are corrupt, but it has been heavily promoted by the media to tap into public anger against corruption and improve the image of the government. The reality is not as severe as the regime claims. Of 1.2 million officials (a large number) investigated by the anti-corruption agency since Xi came to power, only 4.8 percent of cases have been taken to court.

New features of repression

Facing an increase in workers’ strikes and mass protests, state repression is the most serious since the 1989 Tiananmen Square movement. For example on media controls, all newspapers (around 2,000) must now follow the orders of the central government propaganda departments on reporting political news. The wording must be exactly the same. The regime has even cracked down on cultural and entertainment news, to block reporting of gossip about celebrities. They are afraid government officials may get caught up in this gossip. Television dramas involving themes like gangsters, smoking, sex, LGBT, and witchcraft are banned. Mobile phone dating apps for LGBT people are banned.

State repression is also extending overseas. More and more Southeast Asian countries are supporting China’s attacks on democratic rights in Hong Kong and Taiwan. After the kidnapping of booksellers in Hong Kong in 2016, this year a Taiwanese labour activist was arrested in China and charged with subversion. The regime wants to show its power to increase its control over Hong Kong and Taiwan and block ideas of independence.

In Hong Kong, a new government has been appointed by Beijing, through the fake election process involving just 1,200 elite voters. The new leader (Chief Executive) in Hong Kong, Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor, was the 2nd most senior figure of the last government. Her government is continuing the former’s attacks on democratic rights, which have hugely escalated since the defeat of the Umbrella Movement in 2014. For example, four legislators, including the radical left legislator ‘Long Hair’ are now disqualified by the court. This is a parliamentary coup, the most serious attack on democratic rights since China took over in 1997. This means the bourgeois semi-democratic institutions in Hong Kong, like the pseudo-parliament and courts, are now almost completely controlled by the Chinese dictatorship.

Political reform?

Xi Jinping is forced to try to centralise power within the Chinese state because of its weakening grip over regional governments and their increasing unwillingness to follow Beijing’s orders on economic policy. The liberal bourgeois layer in China is extremely weak as the vast majority of the bourgeois class is connected to the regime (over 90 percent of the super-rich are relatives of government or military officials). The liberals’ programme is extremely limited and far from democratic.

Unless facing mass revolutionary upheavals, Xi’s regime is unlikely to make significant democratic concessions, not even like the pseudo-parliamentary democracy introduced in Burma. We cannot rule out Xi’s regime could make concessions if its faces the threat of being overthrown.

But the main feature today is the Chinese regime’s fear any small reforms will trigger mass revolutionary waves and hasten its overthrow. More than other ruling elites, because of the peculiarities of China’s development, they fear the state would begin to break apart into warring factions if they allow limited democratic freedoms. They fear the territorial break-up of China under these conditions and that is not completely unrealistic.

The permanent revolution is more applicable in China today in the struggle to transform what is a unique form of state capitalist dictatorship because the bourgeois class is extremely dependent on the current state; the remaining bourgeois democratic tasks (democratic elections, resolution of national question) must be carried out by working class people. The working class will not stop at bourgeois democratic change but carry out socialist revolution.