An unequalled analysis and critique of capitalism, still relevant today

Robin Clapp, Socialist Party (CWI in England and Wales)

The Daily Mail reacted with predictable hysteria when, in May 2017, John McDonnell stated: “You can’t understand the capitalist system without reading Marx’s Das Kapital.”When asked to immediately condemn his shadow chancellor, Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn refused to do so and correctly added that Marx was “a great economist”.

These endorsements are a long way removed from former Labour leader Harold Wilson’s pathetic attempt to put down Marx’s masterpiece in 1963 when he sneered that he hadn’t got beyond the second page footnote.

Wilson’s arrogance reflects a bygone era. The post-war economic boom appeared to have set capitalism on a relentless forward march that was effortlessly erasing remaining class contradictions. A Labour leader’s job was to simply help manage the system, pacifying the working class through the benefits accruing from the ‘trickle down’ effects of increasing wealth, full employment and publicly owned services.

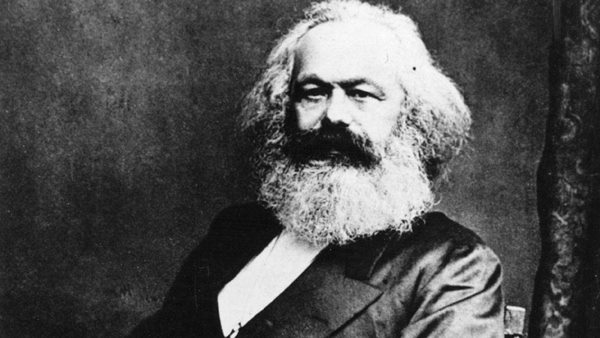

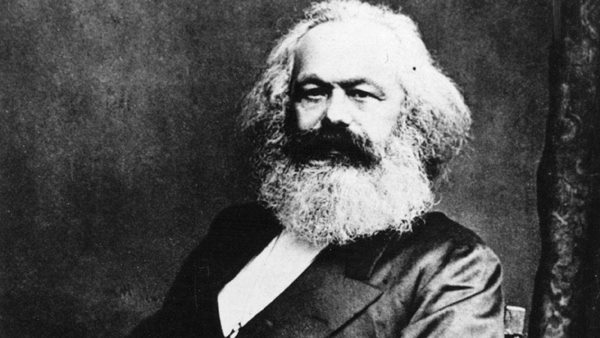

Karl Marx was widely ridiculed as an irrelevant 19th century ideologue. His predictions that capitalism would lead to expanding wealth disparity between the classes and the pauperisation of millions of workers were treated with derision.

Today’s world however, reveals that Marx’s prognoses are once again haunting the bosses as they seek in vain to find a way out of the ongoing damage brought about by the Great Recession of 2008 – which has cost at least $12.8 trillion globally in lost output and $10 trillion in state bailouts.

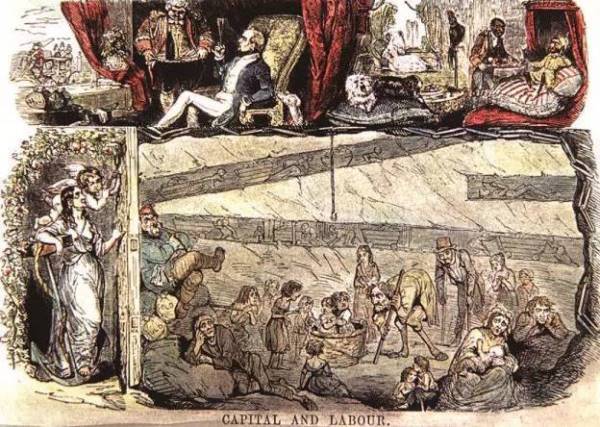

No surprise therefore that the neoliberal Economist magazine should decide to examine Marx’s theories again. In an article entitled ‘Labour is Right: Karl Marx has a lot to teach today’s politicians’, it points to the concentration of capital in fewer and fewer hands, the falls in workers’ wages and the explosion of the casualised ‘Uber economy’ with its insecurity and misery for millions, especially young people.

None of these trends, long ago explained by Marx, are unique to this period. In chapter ten of Das Kapital (Capital), which deals with the working day, he exposes the shocking working conditions and chronicles the degradation young and old alike were exposed to in the name of profit.

He shows how capitalists try to lengthen working hours, or intensify the existing conditions in the workplace in their insatiable quest for more profit. Workers’ safety and general health are ignored as competition between companies and nation states intensify.

The centenary of the mighty Russian Revolution beckons in two months. Yet it is another anniversary on 14 September, that of the publication in 1867 of Volume One of Karl Marx’s Capital, that was to provide the initial theoretical building blocks for the emergence of the party which became the Bolsheviks under the leadership of Lenin and Trotsky in 1917.

Political economy

Capital was published in nine languages while Marx and Engels were alive. The first translation of the three volumes was into Russian. Eager young workers and intellectuals immersed themselves in its pages.

Lenin’s elder brother, Alexander, read it with enthusiasm, recommending it to his sibling. Tragically Alexander was later hanged for attempting to assassinate the Tsar through a desperate and misguided act of individual terror, while the younger Vladimir Ilyich read, learned, put into practice and prepared. Lenin was later to characterise Capital as “the greatest work on political economy”.

Marx’s lifelong collaborator Frederick Engels reviewing the book in 1867, wrote that “As long as capitalists and workers have existed in the world, no single book that could have had such importance for workers has appeared”.

Marx devoted 40 years of his life to the writing of Capital. After his death in 1883, the indefatigable Engels undertook the prodigious task of collating and deciphering Marx’s unfinished notes into what were to become Volume 2 (circulation of capital) and Volume 3 (capitalist production as a whole and its contradictions).

In their works of the 1840s (A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844, The German Ideology, The Poverty of Philosophy, Wage Labour and Capital and The Communist Manifesto), Marx and Engels had begun to formulate the basic propositions of the materialist interpretation of history and the theory of scientific socialism growing out of it.

Capitalist laws

In Capital, Marx discovered the economic law of development of capitalist society. In Volume One he traces the history of the economic struggle of the working class, explains the role of factory legislation in this struggle and analyses the capitalist application of machinery.

Crucially he explains how money becomes transformed into capital as the capitalist accumulates a surplus that is invested for no other reason than to obtain a larger surplus in the next chain of production.

Underpinning every assertion is the application of the ‘dialectical materialist’ interpretation of the historical process to the analysis of capitalist formation. Marx shows that capitalist economy does not develop through a series of random individual acts of exchange, but instead is directed by specific and identifiable economic laws.

He starts Capital with an examination of commodities, which are products of human labour that are exchanged. Capitalist production is, above all, the creation and immense accumulation of commodities.

Every commodity has a use-value. This means they must have use to someone else who will purchase them. Use-value is limited to the physical properties of the commodity. But every commodity has a twofold nature, having also an exchange-value.

While use-values have been produced in every age, only the capitalist social stage of production converts them into exchange-values – goods that are produced not for direct consumption but for sale. Commodities thus have a dual character. They possess a specific form (coat, ice-cream, newspaper, etc) which at any moment may or may not be required by a potential consumer able to purchase them. But also a mysterious hidden property that cannot be worn, eaten or read and lacks material form.

Despite their physical differences, commodities in the market, whatever their use, can be exchanged with other commodities. But how does this happen? What is the mechanism through which different commodities are exchanged?

Human labour

It was Marx who saw that the common thread between all commodities was the expending of human labour on their production, more accurately the purchase by the capitalist of the worker’s labouring power.

At any given period, using the average labour, machines and methods, all commodities take a particular time to make. This is governed by the level of technique in society. In Marx’s words, all commodities must be produced in a socially necessary time.

The value therefore of every commodity is the amount of socially necessary labour time employed in its production.

Supply and demand do not ultimately determine price. A lorry will always be more expensive than a plastic table because of the amount of labour time spent in the production of each respective article. The ultimate expression of this exchange value is money, price being the monetary expression of value.

In selling their labour power, the capitalist enters a contract to pay the worker a wage. Labour power too is a commodity and its value is determined by the labour time necessary for its production.

Marx showed that labour power is a commodity like every other commodity, but yet a very peculiar commodity. It alone is a value-creating force, the source of value and the source of more value than it possesses itself.

Money trick

The great capitalist ‘money trick’ then comes into play. Having agreed a wage, the worker, for example, then reproduces its equivalent value within the first four hours of production. Yet the employer has bought eight hours of labour power and so the worker earns their wage for only half of the shift, while for the other four hours they are creating surplus value, ie working for the capitalist.

Marx explains the process succinctly: “The fact that half a day’s labour is necessary to keep the labourer alive does not in any way prevent him from working a full day.”

The surplus thus extracted is the surplus value or profit – the unpaid labour of the working class – and forms the source of the accumulation of capital.

The class struggle played out in every workplace for more pay or more profit is nothing more than a continual fight for the division of surplus value. Even the dimmest boss instinctively grasps the idea that ‘time is money.’

Marx was the first to understand the source of surplus value. Others like the classical economist Ricardo had identified it but could not adequately explain its origin.

Collating all his previous research into the subject, Marx began a dialectical examination of all the processes of capitalist production, beginning with the analysis of the commodity as its elementary cell-form and the contradictory twofold character of the labour that creates a commodity.

The discovery of surplus value, was to Engels, Marx’s second monumental discovery after historical materialism.

Capital is a treasure trove of ideas that explain the workings of the system with its inbuilt exploitation of workers’ labour power.

Cynical economists who cheerfully confess that they can predict nothing about their system’s tomorrow, never mind its longer term prospects, nevertheless claim that economics is too complicated for ordinary people to understand.

Revolution

For us, as for Marx, a study of political economy strips bare the economic forces that govern our lives and shows their interaction on social developments, history, politics, culture and the class struggle.

In evaluating Capital, Trotsky wrote in 1940: “If the theory correctly estimates the course of development and foresees the future better than other theories, it remains the most advanced theory of our time, be it even scores of years old.”

Today, as capitalism becomes ever more discredited – facing political, social and economic impasse – workers around the world will once again study Capital and the other works of Marxism, always remembering Marx’s famous maxim that “philosophers have hitherto only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it.”