The system of world capitalism faces an unprecedented crisis and turmoil in international relations

Editorial, chinaworker.info

In March, Xi Jinping was crowned China’s ruler-for-life. It was a historic moment, signifying an unprecedented degree of control over the CCP-state.

Since then, things have not gone well. On 6 July, the long feared trade war began between the US and China, the world’s two biggest economies. China’s trade ministry called it “the largest trade war in economic history”. That is a somewhat exaggerated statement – for the time being. But an escalation of this tit-for-tat conflict now looks increasingly likely as our in-depth article Trump’s trade war draws closer on chinaworker.info explains.

Read more: Trump’s trade war draws closer ➵

A trade war of this type has not been fought in today’s globalised capitalist economy. The capitalists themselves don’t fully know the effects this can have in disrupting global supply chains. Of the initial US$34 billion in Chinese exports targeted by Trump’s tariffs on July 6, US$20 billion (58 percent) is produced by foreign companies including US-owned companies, according to Gao Feng of China’s Ministry of Commerce.

The international outlook has therefore darkened considerably in the past few months. Donald Trump’s trade war has increased tensions between the US and all the major economic powers, not only China. However, China is the main target. Trump has so far implemented tariffs on US$100 billion worth of goods worldwide, but has threatened tariffs on a further US$800 billion worth. China accounts for over half of the total.

Economists are warning of serious fallout for the global economy if the conflicts are not contained. There is growing pessimism on this point. While a deal could be reached between the US and China to avert further escalation, such a deal might not last long. It is equally possible the conflict could drag on for years.

Martin Wolf, the Financial Times chief economics commentator, says Trump is engaged in a “war on the liberal world order” built up primarily by the US itself over 70 years. Trump has even threatened to pull out of the World Trade Organisation if “they don’t treat us properly”. The trade war policy of the US government, a sharp reversal of its post-WW2 role, means we are at a historic turning point for global capitalism.

As we have explained this shift is not only or primarily due to the personality of Trump. The capitalist crisis that began in 2008 brought about seismic changes. The political and economic processes behind rapid capitalist globalisation in the preceding three decades have now partially reversed. The capitalist class of each country, while singing the praises of open markets and globalisation, is turning to protectionist policies.

According to an IMF report from 2017, world trade in goods and services has grown by just over 3 percent a year since 2012, which is less than half the average rate of expansion of the previous three decades. For foreign direct investment we see an actual fall. Global FDI fell by 23 percent in 2017, to $1.43 trillion from $1.87 trillion a year earlier, according to the UN Conference on Trade and Development.

The sharp falls of the yuan and Chinese stocks during recent weeks are clear warning signs the Chinese economy is slowing again. Investment and consumer spending – twin drivers of GDP – both seem to have seen growth falling sharply in the second quarter.

The main factor behind this slowdown and the panicky stock market is the credit crunch brought about by the government’s yearlong crackdown on shadow banking and financial risk. The trade conflicts with Trump are a supplementary factor, but one that can increase in importance in the months ahead.

The government’s deleveraging campaign which aims to avert a potentially regime-threatening financial crisis has led to a sharp reduction in investment growth as companies access to credit is cut. The really bad news here is that it underlines just how addicted to debt the Chinese economy has become. Gary Liu, president of the Shanghai-based China Financial Reform Institute, told the New York Times the credit squeeze has been severe during the spring: “It’s very bad, and we see not just small and medium-sized enterprises defaulting but even big companies defaulting”.

In June, the stock market sank to its lowest level since January 2016. US$2 trillion has been wiped off share values in the first six months of 2018, making China’s stock market the world’s second worst performer after Argentina. This is not yet on the level of the 2015 market meltdown when China’s stock market lost half its value, US$5 trillion.

The Wall Street Journal’s Shen Hong points out an important difference between today’s bear market and the 2015 version, that this time the selloff in shares seems to be driven by big institutions rather than China’s army of small stock market investors.

“The economy was in better shape in 2015, and the stock market had rallied for a long time before the crash. There was also no trade war at that time,” said Amy Lin of Capital Securities.

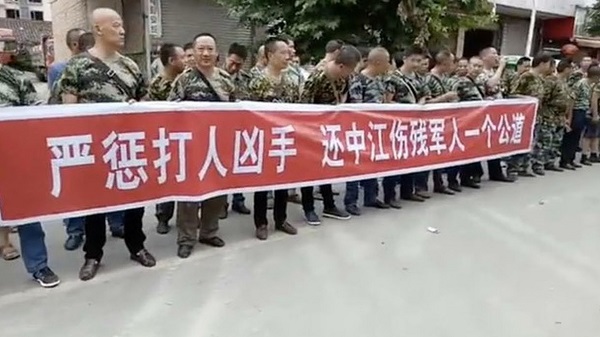

At the same time, workers in China have staged a number of bold and coordinated multi-provincial strikes in the construction, transport and service sectors. Big protests by army veterans in several provinces in May and June forced the government to hold crisis meetings in late June , to speed up measures to end the protests and put some ‘flesh’ on the bare bones of its new Ministry of Veterans Affairs.

The upsurge in the class struggle, despite workers conspicuously avoiding political slogans, is another major problem for Xi’s regime. While China’s economy is now slowing, many groups of workers have reached breaking point as their wages and working conditions have worsened over recent years.

These developments put Xi’s elevation to absolute ruler into perspective. Evidently, the near unanimous decision of the March National People’s Congress has not given the president ‘absolute control’ over the stock market, or the capitalist trading system, or the class struggle. The events now unfolding show the limits of Xi’s ‘unprecedented’ power. His is a regime pressed on all sides – at home and abroad – which will be forced to strike a very delicate balance or risk triggering bigger crises.

The falling yuan, which lost 3.3 percent against the dollar in June, a record monthly drop, and is down 6 percent from March, is part of a wider global trend as ‘emerging markets’ from Turkey to Brazil feel the impact of interest rate rises by the US central bank. This has the effect of tightening credit conditions around the world. Capital is flowing back into US dollar assets, which also strengthens the US currency. Countries and companies that have borrowed in dollars, a cheap option over the past decade, now face bigger debt servicing costs.

The Chinese government may welcome the yuan’s slide, as yet modest, but still the most significant fall since the mini-crisis of 2015. This can be an extra lever of pressure against Trump as a warning that further US trade sanctions could push Beijing into a bigger devaluation.

But while the regime may win some bargaining advantage from a limited ‘tactical devaluation’, a more substantial devaluation would create tremendous problems for the Chinese economy. This would likely trigger a wider global currency war in which economies that are closely connected to China (South Korea, Australia, Japan, Taiwan) would also feel the pressure to weaken their currencies, unleashing a potential ‘race to the bottom’.

Read more: Can Xi Jinping defuse China’s debt debt bomb? ➵

A weaker yuan could blowback on China by reigniting massive capital flight as happened in 2015, when a whopping US$1 trillion left the country. Among other things, capital flight would aggravate the credit squeeze on Chinese companies. It makes it harder, more costly, for the central bank to use monetary stimulus (increasing the money supply and credit) to prevent a sharp drop in GDP growth (hard landing).

The government is already back-pedalling on Xi’s “three year” crackdown on shadow banking and financial risks, because of the credit crunch this has created.

The PBoC (People’s Bank of China) has been forced to shift from credit tightening to loosening. This policy shift could become more pronounced in coming months with a possible return to outright ‘pump-priming’, new stimulus and infrastructure spending to support economic growth. This of course would further aggravate China’s debt build-up, which is unique in world history, and which gave rise to the financial crackdown in the first place. The government will probably try to disguise any such policy shift, using manipulated data and strict press controls, to show its policies are “consistent”.

Censorship is also increasing over other areas of economic policy. The propaganda department is enforcing strict media controls on reporting the trade war as leaked censorship instructions from 29 June show (published on US-based China Digital Times).

Under the ban Chinese media cannot directly report any statements by Trump or his officials. Significantly, the media are no longer allowed to mention the government’s ‘Made In China 2025’ industrial modernisation plan. Accordingly, while Xinhua news agency carried 140 reports on ‘Made In China 2025’ in the first five months of 2018, there has been nothing since June 5. Similarly, state media has been rapped on the knuckles for “exaggerated” reporting with statements such as “the US is scared” and “China as number one country in the world”.

Another example is ZTE, once held up as a symbol of China’s technological greatness. That company’s massive dependence on US-made components has led to a humiliating ‘rescue’ deal – still facing opposition from the anti-China chorus in the US Congress. The ZTE deal is reminiscent of the ‘unequal treaties’ of the colonial era and not surprisingly is also a heavily censored topic in China.

This change of tone by state media represents a very significant (but of course unannounced) political u-turn by the government. Xi Jinping demonstratively abandoned Deng Xiaoping’s mantra, “hide our capabilities and bide our time” in favour of nationalistic chest beating. This has been an important component of Xi-ism, which has been blown up to gigantic proportions by a regime-manufactured personality cult. Without a doubt there are many in China’s ruling elite who are now saying, under their breath, that Deng had a point.

Read more: Xi Jinping aims to be “dictator for life” ➵

Xi himself now feels the pressure that too much nationalism is a constraint on his ability to back down or make deals with the US. This could even undermine his position if he is seen as weak.

The contradictions are piling up for the Chinese regime, which suffers from an overblown faith in the power of its state capitalist economic interventions combined with authoritarian control and a “strong leader”.

The system of world capitalism faces an unprecedented crisis and turmoil in international relations. Trump is just one symptom of this crisis. Only the working class, in China and globally, based on the programme of genuine socialism and international working class solidarity can steer humanity out of this crisis.