Crisis in Czechoslovakia provided a welcome diversion for the Chinese regime, an opportunity to exploit the Russian bureaucracy’s difficulties

Vincent Kolo chinaworker.info

The invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968 by its “sister states” – the Stalinist one-party regimes of Russia and Eastern Europe – produced splits and intense debates within the international labour movement.

In China, another Stalinist regime, with a bureaucratic ruling strata that hid behind the labels ‘Marxism’ and ‘Leninism’ to defend its power and privileges, the Soviet invasion was seized upon to sharpen the CCP’s propaganda offensive against the Russian Stalinist regime.

China was in the midst of the Cultural Revolution and by 1968 Mao was increasingly using the army to crack down on “anarchy” and disarm sections of the workers and students in many parts of China.

The international crisis in Czechoslovakia provided a welcome diversion for the Chinese regime, an opportunity to exploit the Russian bureaucracy’s difficulties and win propaganda points by opposing military aggression. This was completely hypocritical however. In 1956, Mao’s regime had fully supported the Russian Stalinists’ invasion of Hungary to “crush capitalist counter-revolution”. In reality, the mass movement in Hungary was an anti-bureaucratic workers’ uprising rather than a pro-capitalist movement.

The invasion of Czechoslovakia which began on 20 August 1968 was condemned by Chinese radio as a “monstrous crime”. Premier Zhou Enlai attacked the “savage fascist nature” of the invasion by the “social imperialist” Moscow regime.

Many socialists and left-leaning youth around the world were outraged by Moscow’s actions, while also seeing through the crocodile tears of the Western “democracies” – US imperialism was stepping up its barbaric war in Vietnam and Indochina. Significant layers of students especially turned to Maoism believing it offered a more progressive “anti revisionist” left model to the Soviet Union. New Maoist parties and groups began to sprout up in and around 1968 with many thousands of members in Italy, France, Germany and other countries. Mao’s Little Red Book became the most printed book in the world by the early 1970s.

Sino-Soviet conflict

The conflict between the world’s two biggest Stalinist regimes, the USSR and China, grew out of the rival national interests of the two bureaucratic elites. Their primary concern was not “socialism” but to protect their own power and privileges. This was itself proof that these societies and regimes, despite the abolition of capitalism and introduction of state planning, were miles away from real socialism with democratic workers’ control over the economy and the state.

Their inability to overcome national rivalries prevented cross-border economic integration and the achievement of economies of scale, thus cancelling out many of the potential benefits of a planned economy. This later became a decisive factor in the collapse of Stalinism and the restoration of capitalism.

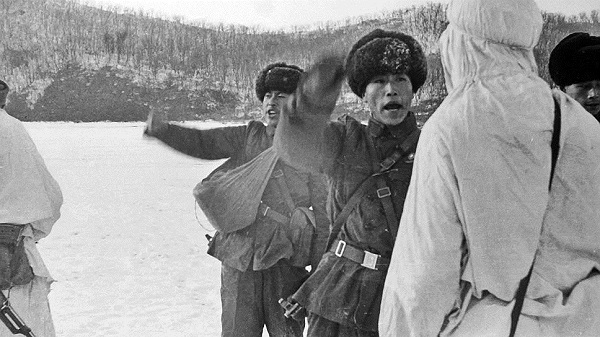

The 1960s saw a deepening split between Moscow and Beijing, and even a small-scale border war that rumbled throughout 1969 causing over 100 fatalities. These tensions prepared the ground for the Chinese regime’s historic diplomatic flip-flop in 1971, allying with US imperialism against the Soviet Union, thus strengthening US imperialism and undermining the global struggle against it.

Chinese propaganda consistently accused the Russian Stalinists of being soft towards the US and wanting an accommodation with it. This was even said in relation to Czechoslovakia, despite the invasion provoking a serious diplomatic standoff between Russian Stalinism and the Western capitalist bloc.

Stalinism never worried about such glaring inconsistencies. Mao’s regime, like Stalin and his successors, would flip from one position to another even diametrically opposite position without explanation. In Stalinist parties and regimes there were of course no democratic discussions – the “omniscient” leadership would decide all questions based on defending their own power and prestige.

Mao’s regime had opposed and distrusted the Czechoslovak leader Dubcek’s political reforms in 1968 and the mass pressure these had unleashed (the ‘Prague Spring’). The Chinese bureaucracy feared this example would undermine its authority internationally and could even gain an echo in China. Dubcek was instead held as an example of the “decay” and “revisionism” within Moscow’s camp. The line changed abruptly after the invasion, which took Beijing by surprise.

Nationalism

Beijing opposed the invasion and subsequently denounced the “betrayal” of Dubcek in capitulating and urging the masses not to resist the Russian-led occupation. But the Chinese arguments were purely nationalistic. Dubcek had betrayed his “country’s interests”. The issue was “national sovereignty” not the democratic and political rights of the workers or how to fight for genuine socialism. Eleven years later, in February 1979, China under Deng Xiaoping would invade Vietnam, another “socialist” country, without much concern for its “national sovereignty”.

CCP propaganda called for a “national resistance movement” by the people of Czechoslovakia against Moscow, but this was an empty slogan devoid of any practical strategy. It invoked the idea of rural guerrilla warfare – madness in a heavily industrialised and urbanised society like Czechoslovakia. There was no mention of the interests of workers in Czechoslovakia and the wider region.

That Stalinism and capitalism could only be defeated by democratic workers’ control and an international struggle to eliminate capitalism, casting off the unaccountable rule of the bureaucrats in the Stalinist states and ruling instead through elected workers’ councils, this was of course absent from their critique.