Stonewall itself had roots of its own, in the movement that developed against the Vietnam War, which not only helped to crystallize a gay political identity but set the stage for decades of queer organizing to come

Greyson Van Arsdale, Socialist Alternative (ISA in the United States)

This Pride month will mark the passage of eight months since Israel’s invasion of Gaza, which has killed over 35,000 people and injured many thousands more. Millions are now displaced, and Israel’s ground invasion of Rafah and the threat of mass starvations threatens to ratchet the casualty count to a far higher level.

Many young queer people have been at the forefront of anti-war protests in the US, most especially the outbreak of student encampments on college campuses that began in April. As school lets out for the summer, the anti-war movement will be searching for its next evolution, and many young people will bring an anti-war consciousness to Pride celebrations and demonstrations.

But this is not the first time that queer youth in America have played a role in fighting against a brutal war. In fact, the evolution of the queer liberation movement in the US has not just been influenced but in some ways has been born from militant anti-war struggle.

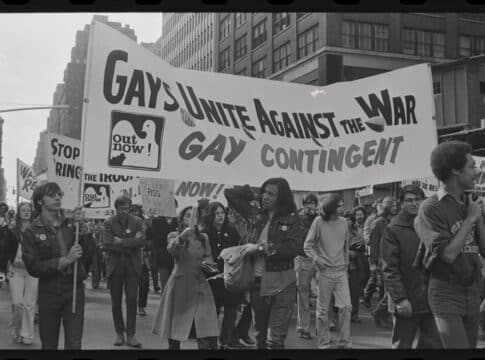

It has long been said that Pride has its origins in a protest, in a riot, at the Stonewall Inn in 1969. This is true, and the struggle is ongoing to reclaim Pride’s radical origins in Stonewall’s tradition. But Stonewall itself had roots of its own, in the movement that developed against the Vietnam War, which not only helped to crystallize a gay political identity but set the stage for decades of queer organizing to come.

Before Stonewall

Though it was the US ruling class who launched the war as part of their global struggle against “Communism” during the Cold War and because of the social revolution in Vietnam, it was ordinary people who were tasked with prosecuting the violence. The Vietnam War took millions of people from their lives and into the arena of war and expected them to kill, and this had a deeply radicalizing impact. Across the war two million people were drafted and over 40,000 Americans were killed — this was disproportionately borne by the working class and poor, since full-time college students were eligible for draft deferment.

As non-draftees in America began to see the violence televised, and hear back stories of people they loved being injured and killed, this transformed distaste for the war into outright dissent, and finally, into drastic action.

But different communities felt this radicalization in different ways. For young draft-eligible queer people, the Vietnam War also created a certain pressure to come out of the closet.

Being gay, or having “homosexual tendencies” as the draft asked, was a disqualifier to join the military. Answering in the negative, if untrue, could result in a dishonorable discharge, which could greatly impact your life and make it difficult to get work. But if you answered in the affirmative, it was likely you’d be forced out of the closet, since draft information was public. But as avoiding the draft became of paramount importance for many, both as lifesaving action and as political expression, more and more young queer draft-eligible people took the option of “coming out” against the war, so to speak. The Vietnam War created pressure towards the development of a gay political identity, beyond a personal sexual identity, that we recognize today.

At the same time, mass demonstrations against the war were building, which gave gay liberation groups an opportunity to step out of the shadows, emboldened by a movement that over time increasingly became not just about the Vietnam War but linked to other struggles including the Black Freedom movement and the women’s liberation movement. A May Day anti-war demonstration in 1969 contained an organized gay contingent, before the Stonewall riot took place and set off the modern era of gay rights organizing later that year.

The horror of the Vietnam War also drew a clear line through gay activist circles over what constituted “progress”. Integration into the armed forces had long been a demand for gay equality, but the movement against the war convinced many that it was no measure of equality to be allowed into military service. Gay liberation groups that erupted during this period, like the Gay Liberation Front, steadfastly opposed the demand of integration into the military, setting the stage for even more radical expressions of the movement for queer liberation.

This was a marked change from gay advocacy organizations that had cropped up in the aftermath of WWII, like the Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitus, who saw dishonorable discharges from the military for being gay as socially and economically disastrous, and integration as necessary to win respectability for queer people.

The war in Vietnam transformed this consciousness, and set the stage for the explosion of struggle at Stonewall Inn in 1969, and for a new vision of what it meant to be freely queer.

Different struggles, same fight

The movement against the war in Vietnam taught a generation of workers and youth how to fight against the capitalist regime, which fomented war and brutality abroad and oppression and poverty at home. It was a proving ground for the activists that would later participate in the movement that started the Pride month we still celebrate today, but it wasn’t just pivotal to the queer liberation movement. The movement against the Vietnam War drew energy and inspiration from the Civil Rights movement in the 50s which preceded it, and contributed to the radicalization into the Black Power movement of the 1970s, and bolstered feminist struggle which led the biggest womens’ rights demonstration in US history in 1970 and won Roe v. Wade in 1973.

Over the last decade, many young people have come to intuitively understand that different oppressed identities overlap, or “intersect”. Though the term “intersectionality” was coined to describe how the lives of individuals are concretely shaped by different oppressions — racism, sexism, queerphobia, ableism — that combine and synthesize into unique forms, new generations understand that it’s not just personal experiences but the struggles themselves that are related.

But how are they related? A better word than “intersect” might be “co-depend.” The struggles of each experience are united by our exploitation as working-class people, which gives us a common interest against the will of the ruling class that pits us against each other for no one’s benefit but the wealthiest of society.

Martin Luther King, who came out vocally against the war in 1965, put it this way in his famous speech “Beyond Vietnam” in 1967: “This query has often loomed large and loud: Why are you speaking about the war, Dr. King? Why are you joining the voices of dissent? Peace and civil rights don’t mix, they say. Aren’t you hurting the cause of your people, they ask? And when I hear them, though I often understand the source of their concern, I am nevertheless greatly saddened, for such questions mean that the inquirers have not really known me, my commitment or my calling. Indeed, their questions suggest that they do not know the world in which they live.”

“We have been repeatedly faced,” King said, “with the cruel irony of watching Negro and white boys on TV screens as they kill and die together for a nation that has been unable to seat them together in the same schools. And so we watch them in brutal solidarity burning the huts of a poor village, but we realize that they would hardly live on the same block in Chicago. I could not be silent in the face of such cruel manipulation of the poor.”

The capitalist system uses oppression to divide the working class, which outnumbers the capitalists internationally by a margin of billions. This means that all workers, regardless of identity, have a vested interest in overcoming oppression — because it is the obstacle in the way of workers fighting together against the main enemy in society, a rich and powerful few who make trillions in profit at the expense of everyone else. In this way, movements against oppression are dependent on one another, and compound each others’ progress. The example of the movement against the war in Vietnam is a profound display of this happening in practice, and of working-class people of different experiences learning from each other how to lead bold struggles against oppression.

Gaza & queer struggle today

Queer people in the United States are in an increasingly embattled position. Since a wave of right-wing backlash overtook the country in 2022 and 2023, the legal rights of trans people have been dramatically curtailed in many states. Today, 38% of transgender youth live in a state where gender-affirming care for minors is banned. About the same number live in a state where transgender athletes are banned from playing sports. Eleven states ban transgender people from using public bathrooms of their gender identity, and in two of those states, it’s a criminal offense to do so.

Pride month in the last two years has been overcast with a feeling of unease, fear, and at times even desperation at the state of queer rights being rolled back from a position of progress over the last decade. Queer youth, sometimes alone and isolated in their schools and communities, looked for ways to fight back, but valiant efforts at building a protest movement weren’t able to stand up to the right-wing onslaught in most cases.

Now, the same queer students who were juniors and seniors in high school are freshman and sophomores in college, many of them likely on campuses where Gaza protest encampments have been organized. What lessons are they learning about how movements win? Over time, they have concretely seen international court action fail to stop Israel’s murderous campaign, and even successful motions by the UN against the violence fail to have an impact. They have seen their own actions in mass protests and viral campaigns transform consciousness in the US and create enormous pressure to call for a ceasefire, and most recently, they have seen President Biden endorse and vocally support police action to abuse and remove students from protest encampments.

What might queer students conclude, then, about the fight against queer oppression in the US? If the Democrats are so unapologetically sending weapons to Israel to execute a campaign of mass murder, can they be the party of queer equality? If Biden so readily endorses sending police to crack down on anti-war protesters occupying space on the very campus they live on and pay tuition to, is it any measure of success for the movement to have his support for transgender rights? Is it more powerful to win victories through pushing for court action, or is it better to build protest action and even civil disobedience in the streets, workplaces, and schools?

The conclusions drawn from the movement against the war on Gaza can draw queer struggle to the next stage of its fight — for demands that will bring us into open conflict with the Democratic Party, like Medicare For All including gender-affirming care and abortion on demand, massive expansions in affordable housing paid for by taxing the rich, and for labor unions to organize mass non-compliance with anti-LGBTQ laws in hospitals and schools. A militant fight for what queer workers and youth actually need is necessary to take the momentum away from the right wing and towards building a world of genuinely free expression.

For a socialist world

The heights of the movement against the war in Vietnam are very different from the anti-war struggle we see today. In Oakland, California, in the six months leading up to March 1970, 50% of those called to the military failed to report for duty. By 1972, there were more conscientious objectors to the war than there were draftees, and there were 245 individual newspapers being published and circulated by rank-and-file soldiers, with names like Out Now! and Star Spangled Bummer. The street movements were much larger than we see today, with two million Americans demonstrating against the war on October 15 of 1969, and 14,000 arrested — the largest mass arrest in US history. Of course, by the time the anti-war movement reached its height, the US war had been going on for a decade and a half since 1955, escalating after the start of Operation Rolling Thunder in 1965.

The movement against the war in Gaza is in a weaker position — not just because US troops are not directly involved, but also because of the weakness of organizations of the working class and of struggle in the twenty-first century. Labor unions, despite often having reactionary pro-war leaderships, once were centers of not just economic but political struggle — but they have now been eroded by decades of attacks and are only just starting to get back on their feet. Activist organizations which once had memberships numbering in the tens of thousands are now advocacy NGOs, connected now more to the establishment of the Democratic Party than they are to the lives of working-class people.

Building back this capacity and re-learning the lessons of the past is an all-sided struggle — from the anti-war movement, to the movement for queer liberation, to the fight against racism and against sexism and gender oppression.

The era of the Vietnam War shows us the enormous power of mass struggle. Popular resistance ended the Vietnam War, both on the ground in Vietnam by guerrilla fighters and the movements eroding the will of the military to fight from the United States. The late sixties and early seventies were explosive for all struggles, and ultimately the thing missing was a mass workers party which could have united the struggles and pointed towards their ultimate conclusion: a confrontation with the capitalist system itself, and building a united fight to overturn that capitalist exploitation and win a socialist world.

Today, the need for that united fight still remains.