“The capitalist CCP dictatorship can be fought in Hong Kong, but it can only be defeated in China”

chinaworker.info reporters

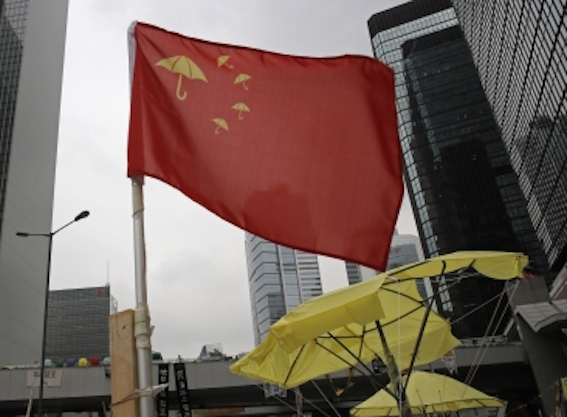

On 28 September, 2014, what became known as Hong Kong’s Umbrella Revolution began. The police launched a savage tear gas and pepper spray assault on thousands of peaceful protesters who resisted using umbrellas as shields. This youth-led protest movement developed in opposition to Beijing’s imposition of an Iran-style rigged-election model to decide Hong Kong’s ruler or Chief Executive. The so-called “831” ruling (on August 31, 2014) from the NPC Standing Committee, an appendage of the CCP dictatorship, marked a key milestone in a years-long struggle for democratic rights and against dictatorial rule.

To this day, the forces and ideas represented in this struggle are blurred and misrepresented not only by the Communist Party (CCP) controlled media, but in equal measure by overseas media who only focus on a few liberal “personalities”, or on “students”, the only social forces most journalists can identify with.

Below we republish articles by Hong Kong ISA members from 2013 and 2014. Our warnings that the CCP regime wanted to further strangle democratic rights in Hong Kong and crush the democracy movement have unfortunately been brutally confirmed. We said the struggle against authoritarian rule in Hong Kong could only succeed if it spread and linked-up with the masses in China. This has also been proven by subsequent events.

The Umbrella Movement ended after 79 days, still the longest continuous occupation of a major city in history. The struggle reached an impasse, but was not decisively defeated. A counter-revolutionary offensive by the Hong Kong government and CCP regime attempted in the following years to push back and subdue the democracy struggle. But in 2019, this counter-revolutionary “whip” provoked an even bigger and potentially revolutionary movement, with over two million marching. That struggle lasted a half-year until the pandemic of 2020, amplifying the exhaustion and sense of complete stalemate after months of exertions and clashes with the state forces, would enable the CCP to strike decisive blows against the democracy movement in Hong Kong. What followed in the four years since was mass arrests, closure of regime-critical media, the dissolution of most trade unions, new draconian national security laws and a ban on all protests.

The forces of ISA in Hong Kong (our international was then known as the CWI) was active in the 2014 and 2019 mass struggles not only from day one, but in the preceding years, intervening in countless mass demos, meetings, occupations and assemblies, outlining our socialist analysis of which politics and fighting methods were needed to defeat the world’s wealthiest, most well-armed and digitally advanced dictatorship.

This was a different time. Before the current imperialist bloc conflict made it fashionable for right-wing politicians and governments in the West to denounce autocracy in China and pose as defenders of democracy. In 2014, most “democratic” foreign governments adopted a low-key stance over the Hong Kong events. Their profits squeezed out of China’s vast non-union labour force were far too important to upset by making ‘political’ statements.

Britain’s foreign ministry in 2014 published a statement telling the Hong Kong people to accept Beijing’s anti-democratic deal as “the best offer” they could get. Only later did American and other western politicians feign support for those resisting the dictatorship. Unlike these capitalist hypocrites, ISA can reprint our articles and documents from that time and stand by every word. The lessons of these struggles will be crucial in the coming years when new revolutionary movements will shake China and the whole world.

Vital lessons of Hong Kong’s ‘Umbrella Revolution’

Mass struggle needs genuine internal democracy and a fighting working class programme to defeat the CCP dictatorship

(First published on chinaworker.info on 19 November 2014)

The epic ‘Umbrella Revolution’ has raged for seven weeks, now holding out for longer even than the historic Tiananmen Square mass movement that was crushed in 1989. The current Hong Kong protests constitute the most serious challenge to the Chinese dictatorship (CCP) and the Hong Kong capitalist elite since the Beijing events of a quarter century ago.

The demands of the mostly youthful protesters for free elections have won massive support in society. At the same time, the movement reflects explosive social discontent in Hong Kong, one of the most unequal societies on the planet. In a Reuters poll conducted in October, 38 percent of those at the three protest sites cited ‘wealth inequality’ as a major reason for joining the struggle. Nor is this a ‘student movement’ as widely portrayed in the media. The same poll found that only one in five of under-30s in the occupied areas are students.

At the time of writing a new offensive is being prepared by Hong Kong’s unelected government with the imminent launch of a mass police clearance exercise. With 7,000 police on standby and high court judges deliberating over the exact wording of court injunctions to clear the occupied sites, this attack could take place within hours. This follows a three week hiatus in which the government has played a waiting game, while stepping up its psychological warfare against the protests. Orders to cool things undoubtedly came from Beijing and China’s ‘supreme leader’ Xi Jinping, who did not want his prestigious APEC summit, attended by 22 government leaders including Obama, to be upstaged. With the APEC banqueters returning home the signal has now been given for the ‘gloves to come off’ in Hong Kong.

Previous police assaults on the protest sites have triggered a powerful backlash, with thousands mobilising, forcing the government and the state to step back. However, this time the outcome is less certain given evident splits and a crisis of leadership within the protest movement. Socialist Action, the Hong Kong supporters of the Committee for a Workers’ International (CWI), have consistently criticised the bourgeois democratic politicians (pan democrats) and their NGO allies that currently set the political tone within the democracy struggle. These groupings are tied politically to the coat tails of the capitalist class and therefore, given the interests of capitalism in the current dictatorial system in China, expound a very partial reform programme that studiously avoids calling for the overthrow of the dictatorship or spreading the democracy struggle into China. Unfortunately, while in the course of the current mass movement the grip of these compromise leaders has been shaken and widely questioned, with other groups such as the students emerging in a bigger role, these newer forces have continued to follow the mistaken political strategy of the pan democrats, rather than rejecting it for a class struggle orientation that seeks to ignite an even bigger movement inside China against the CCP dictatorship.

We republish here an article from Socialist《社会主义者》magazine (the Chinese language magazine of the CWI) from May-June 2013, which explains the approach of Marxists to the mass struggle in Hong Kong and the role of the pan democratic leaders. This was written shortly after the launch of the ‘Occupy Central’ campaign and, while welcoming the proposal for occupation, takes up the political and organisational weaknesses in the OC leaders’ concept of struggle. As we warned at that time, “The ‘moderate’ pan democratic parties are mainly using ‘Occupy Central’ to secure their own positions as powerbrokers in the coming struggle… These leaders fear mass struggle, which can push them further than they want to go, and even sweep them aside in favour of more resolute forces.” In fact, this is what happened when the ‘Umbrella Revolution’ erupted in September, sidelining the OC leaders as a punishment for their repeated refusal to start the occupation struggle, consigning them to history as a campaign that only ever fired blanks. Currently, the main debate among the OC tops seems to be how and when they will surrender themselves at police stations for supporting an ‘illegal’ protest movement!

As this article warned, “The ‘moderate’ pan democratic leaders have consistently underestimated what is needed to achieve universal suffrage in Hong Kong… An occupation on its own will not be enough to force the Chinese regime to retreat.” From the outset, Socialist Action supporters called for the occupation campaign, “to become a platform from which to launch even more effective forms of mass resistance. These include strikes and calls for solidarity action from beyond Hong Kong’s borders.”

Crucially, this article explains that, “If the democratic struggle in Hong Kong is isolated to Hong Kong (as today’s pan democratic leaders want), and refuses to actively link-up and support mass anti-authoritarian struggle in China, it cannot succeed.”

As the Hong Kong struggle enters a more complex and difficult phase, with considerable dangers present, there are vital lessons that need to be discussed and absorbed in order to go forward.

The great debate about Occupy Central

What kind of struggle can defeat the dictatorial regime?

Dikang, Socialist Action (from issue 21, May-June 2013, of Socialist magazine)

Hong Kong’s struggle for democracy is approaching a critical phase. Spokespeople for the Chinese dictatorship (CCP) have confirmed the warnings of Socialist magazine, that the so-called promise of universal suffrage in 2017 is nothing of the sort. No candidate guilty of ‘confronting’ Beijing will be allowed to run for the post of Chief Executive. The dictatorship intends to exercise final control over who can be elected to lead a government, reducing any election to a mere ‘consultation’. Its echoes in the Hong Kong government camp are stepping up their propaganda war, on the theme that “true universal suffrage is utopia.”

One suggestion for the looming showdown with Beijing over universal suffrage is the plan for Occupy Central (OC) originally floated by law professor Benny Tai Yiu-ting and supported by the main pan democratic parties. The government camp is clearly worried about how this idea can grow and develop and the media is full of dire warnings of political chaos and “economic suicide” in Hong Kong. This we have heard many times before!

‘Occupy’ is not a new idea and no individual or grouping can claim exclusive ‘ownership’. ‘Occupy Wall Street’ and similar huge mobilisations in Europe have grabbed world headlines, inspired by the revolutionary risings in Tunisia and especially Egypt in 2011. If the Occupy Central initiative seeks to mobilise huge numbers, with no attempt to set limits on this; and if an occupation and demonstrations are run in an open and democratic way (which unfortunately was not the case with the very top-down organisation of the Tamar protests against school brainwashing in 2012) then this initiative can mark an important step forward.

What should the aims of a mass occupation be?

A new mass occupation in Hong Kong could be used as a springboard from which to escalate the struggle for real democracy. But to reach that goal will require other more effective methods of mass struggle such as strike action and the building of mass popular organisations based on grassroots workers and youth. Unfortunately, rather than this approach, the ‘moderate’ pan democratic leaders promoting OC envisage a more limited, symbolic occupation, in which the goal is not to inflict a costly defeat upon the CCP dictatorship (without which full democratic rights are impossible) but rather to try to secure what are actually rather marginal concessions. This is a strategy that has failed before, and is no more likely to succeed in future. There is no example in history where democratic rights have been granted by a dictatorial regime – through negotiations – in return for recognising and accepting that regime’s continued rule.

The ‘moderate’ pan democratic parties are mainly using OC to secure their own positions as powerbrokers in the coming struggle, following an erosion of their public support in recent years. This is especially the case with the Democratic Party, which has not been forgiven for its cowardly and treacherous role in 2010 especially, when it voted for an anti-democratic electoral reform package. These leaders fear mass struggle, which can push them further than they want to go, and even sweep them aside in favour of more resolute forces. But they also know that if they do nothing – as the clock ticks towards ‘midnight’ and the 2017 elections – they will be completely discredited. So for the Democrats especially, although many ordinary workers and youth see the idea of an occupation as an opportunity for real struggle, this is an attempt to create a platform for themselves as ‘leaders’, with the aim of trying to contain the movement and prevent it developing into a full-scale challenge to the existing power structure.

The initial idea floated by professor Tai was for a restricted number of demonstrators – Tai proposed 10,000 – to occupy and block roads in Central. There are a number of weaknesses in this concept, in terms of organisational approach and political programme. It is entirely counter-productive (and unrealistic) to try to restrict the size of the struggle or impose other organisational limitations upon it in advance. Tai has also stated he wants the ‘middle-class’ and even the ‘middle-aged’ to dominate this movement. He thus downgrades the two decisive components of any successful mass struggle – the working class and the youth. Unfortunately, the more Tai elaborates his ideas, the clearer it becomes that these ideas are snatched from the air, and completely divorced from real experience of struggle. Even in Hong Kong, without looking further afield, a major trend in political movements of the past five years has been the activism of the ‘post-80s generation’, but this seems to be lost on Tai and his pan democratic allies.

What kind of struggle can defeat a dictatorship?

The ‘moderate’ pan democratic leaders have consistently underestimated what is needed to achieve universal suffrage in Hong Kong. This lack of realism is a major danger in the coming struggle. Tai for example made the incredible statement that, “Ideally, Beijing will have compromised before we need to occupy Central.” [HK Weekend, 18 April 2013]. This is a completely mistaken view. Such naivety and underestimation of Beijing’s position is a congenital defect among the pan democratic tops. Martin Lee, commenting on the start of negotiations between Britain and China three decades ago, made the revealing comment, “It was a different time. We all thought we’d just wait 10 years and then we’d have democracy.” [Wall Street Journal, 9 April 2012].

An occupation on its own will not be enough to force the Chinese regime to retreat. Furthermore, as movements in other countries have shown, without a clear programme and democratic structures a prolonged mobilisation will exhaust the participants without achieving political change. Despite this, as part of a wider strategy to mobilise the masses, escalate to other forms of mass action, and ultimately to spread this movement to mainland China – where it must finally be settled – a mass occupation can play an important role. This is where Socialist Action disagrees with those pan democratic leaders who see OC as the final round, or ‘last resort’ to quote Civic Party leader Alan Leong Kah-kit, rather than a platform from which to launch even more effective forms of mass resistance. These include strikes and calls for solidarity action from beyond Hong Kong’s borders.

More recently, some pan democratic leaders have shifted their stance and now say mass civil disobedience could continue in other forms if OC is forcibly dissolved by the police. This reflects a dawning realisation that an occupation alone won’t force the CCP to back down, but even this new position lacks a real strategy in which the occupation is merely one step in a wider mass political challenge to the dictatorship.

The CCP wants to keep ultimate control over Hong Kong’s political system in one form or another, not because of the consequences in Hong Kong if it lost this control, but because of what could happen inside China. Top CCP leaders increasingly fear revolution in China. Xi Jinping has openly warned of the possible “extinction” of the CCP-state within ten years. To achieve victory, Hong Kong’s struggle for democracy has to be a mass movement and has to link-up with the unfolding revolutionary struggle in China. The masses on the mainland, especially the 400 million super-exploited workers, are the central force that can defeat the CCP regime. If the democratic struggle in Hong Kong is isolated to Hong Kong (as today’s pan democratic leaders want), and refuses to actively link-up and support mass anti-authoritarian struggle in China, it cannot succeed.

At the same time this struggle is not just against the CCP dictatorship. The Hong Kong capitalist class, dominated by a few all-powerful tycoon families, is just as determined to block democratic change in order to protect its mega profits. Some big companies and banks are threatening to relocate from Hong Kong if the occupation goes ahead and causes ‘political instability’. This shows that for the capitalist class political freedoms come a poor second to ‘order’ – for making money. The struggle for democracy will therefore go forward as a struggle against capitalism or it will not go forward at all.

What should the immediate demands of the movement be?

Professor Tai and his pan democratic co-thinkers have so far put forward only vague interpretations of ‘democratic elections’. This lack of specifics allows enormous wiggle room for the Chinese regime to continue with its well-honed tactic of delays, rotten trade-offs and purely cosmetic changes. Tai has said the proposals for 2017 should be in line with ‘Western systems’, but which of these are truly democratic? Not Britain with its House of Lords, and not the US, where the president is elected by an electoral college rather than the popular vote. These so-called ‘democracies’ are designed to hide the de facto rule of the banks and big business.

Tai has also said he could accept a ‘screening mechanism’ for Chief Executive candidates from a reconstituted 1,200-person Election Committee, provided this committee is itself elected through universal suffrage. But this idea – for an election to decide who picks who can stand for election – is not even democratic by the lowest of ‘Western’ standards. If this is the starting position of the pan democratic leaders, how far will they lower their bids once the government and business leaders step up their counterattack? Martin Lee has gone so far as say a screening mechanism is acceptable provided at least one pan democrat is among five candidates chosen by the present establishment-dominated nomination committee “as a whole”. Lee was forced to retract this proposal within 48 hours because of the public backlash. This ‘mistake’ by Hong Kong’s ‘father of democracy’ shows how out of touch the pan democratic leaders are from the mass anger at ground level.

If the masses are not to be sold short again, a clear programme for achieving real democratic change is needed. This must demand the ousting of C.Y Leung and his illegitimate elite-appointed government. It must state clearly that all elitist ‘small circle’ structures such as the Election Committee and Functional Constituencies must be abolished – not ‘phased out’ or ‘reformed’ – and with immediate effect. No screening mechanism (a classical feature of undemocratic regimes) is acceptable. All parties and individuals should be eligible to stand in elections. The movement must reject trade-offs such as linking an election deal to introducing a ‘new’ version of Article 23 [repressive ‘anti-subversion’ legislation that was defeated in 2003]. Even these minimal conditions would not amount to real universal suffrage, because the CCP dictatorship reserves for itself the final word on who forms a government, and therefore any election process is ultimately ‘consultative’!

This is why Socialist Action, while fighting alongside the masses even for partial democratic advances, argues that the democratic struggle is interlinked with the struggle to overthrow the CCP dictatorship and its capitalist allies in Hong Kong and China. We call for the toothless semi-elected Legco to be replaced by a real democratic assembly, elected by universal suffrage by all over 16 years of age, with the power to choose the government and implement urgently needed social change. This should include immediate legislation for a statutory 8-hour work day, an increased minimum wage, fully state-funded universal pension system, massive expansion of low-cost public housing, major anti-pollution measures, and a socialist programme to break the stultifying economic power of the capitalist tycoons.

What about a new ‘de facto referendum’?

In a mass struggle a variety of tactics are needed. The idea of resigning seats in the rubber-stamp Legco to trigger a new election (de facto referendum) is one method. In 2010 Socialist Action actively participated alongside the LSD and others in the ‘516’ movement, which in our view made a significant impact. ‘516’ gathered over 500,000 anti-establishment votes from a radicalised layer who have mostly turned away permanently from the rotten compromise politics of the Democratic Party and other ‘moderates’. This campaign, given the leading role of the pre-split LSD, had an anti-establishment character and reflected pressure from grassroots activists and youth.

If a future ‘referendum’ were dominated by the Democratic Party and Albert Ho Chun-yan, as is now being floated, this would be a very different affair from the last one. As Ho’s farcical 2012 C.E. ‘small circle’ election campaign showed, Ho and the Democratic Party have no rightful claim to be the sole or main spokespeople of the democracy struggle, including such a key episode as a future resignation exercise. Ho opposed the 2010 movement and did his best to reduce its impact, instead supporting fruitless talks with the CCP. If the resignation tactic is now repeated under the control organizationally and politically of the Democratic leadership, this will mean a more ‘moderate’, muted campaign, in terms of slogans and connections to actual struggle, that will fall far short of what is needed.

Socialist Action says that any future ‘referendum’ campaign must instead be based on democratic and open campaign structures, involving a plurality of organisations involved in the democracy struggle, with democratic discussions and decision-making on all key issues.

Should political parties be kept out?

Some Democratic and Civic Party leaders are warning against the possible ‘hi-jacking’ of OC, pointing to unnamed radicals. They also argue that political parties, banners, symbols, and publications, should be kept out of the movement. This is a recipe for an undemocratic, bureaucratically controlled occupation. At first sight this ‘non-party’ argument can appeal to some layers of youth and workers, who rightly view the political parties of the capitalist establishment with scorn. But the question must be asked why is it politicians from these very parties that now hypocritically oppose freedom for political parties? It is obvious that any mass movement, drawing together people from a broad spectrum, that does not allow democracy within its own ranks – the right of different groupings, parties or individuals to openly campaign and put their case – cannot create a democratic society.

The call to ban different parties has been borrowed, paradoxically, from the Chinese dictatorship. Similarly, it is a contradiction in terms for any truly democratic leader or organisation to raise complaints about the possible ‘hi-jacking’ of a demonstration or struggle. This echoes the CCP’s cry of ‘black hands’, which it routinely uses to discredit mass protests in China. Both accusations hold the masses in contempt, portraying them as unthinking pawns to be manipulated or ‘hi-jacked’ by ‘outside forces’. This type of argument reveals a desperation and insecurity among the pan democratic tops – to keep the movement within tight controls and guard against so-called ‘radical forces’ gaining in influence. This is not the first time these leaders have manifested an essentially ‘small circle’ bureaucratic approach to mass protests.

The establishment politicians dominate the debate in the media, but at the same time largely lack real forces: mass parties and activists on the ground. This is part of an international phenomenon whereby politics has been ‘Americanised’, dominated by massive media and advertising budgets, winning votes but totally lacking roots among the masses. This fate has befallen the former workers’ and left parties, which have shifted to the right and become pillars of the capitalist establishment, and this is why Socialist Action and our international co-thinkers in the CWI call for the formation of new fighting working class parties. History shows that such parties are essential weapons in the struggle for democracy.

Politicians who dread real struggle and confrontation, and always veer towards compromise, have no need or wish to campaign openly for their ideas on the streets or among a crowd of demonstrators. Their ideas are echoed and promoted by the establishment-controlled media and they seek support from the least conscious, inactive layers, rather than those on the frontline of struggle. For the mass struggle on the other hand, it is a positive for the political affiliation (or lack thereof) of this or that platform speaker or leading activist to be out in the open. The Democratic Party establishment and their allies oppose this democratic, transparent approach to building a movement, because they prefer to hide their real political agenda, which is more suited to backroom negotiations with the government.

What lessons should be drawn from the Tamar occupation against school brainwashing?

The Tamar movement [September 2012] grew into a gigantic 9-day occupation with crowds of over 100,000. But the movement was controlled by a small unelected group, dominated by the PTU bureaucracy (Democratic Party politicians) and its allies within certain NGOs. The school student group Scholarism, which was artificially credited with ‘leading’ the movement, became very popular and recognizable from the mass media. But rather than a democratic membership-based organisation, Scholarism was little more than a facebook group dominated by one or two media ‘personalities’. This loose formation with no clear strategy (beyond ‘opposing’ national education) proved very easy for the PTU bureaucrats to manipulate and, to use their term, to ‘hi-jack’. Thus a mass protest movement that had CY’s government on the ropes was sold short. Its leaders, without the slightest democratic consultation, cancelled the movement suddenly, and settled for a semi-retreat that still gives the government camp the option to revive the school brainwashing plan at a later date.

In OC, the place of Scholarism has been taken by professor Tai – a ‘new face’ for the same coterie of Democratic Party allies to hide behind. We say that any mass movement such as ‘Occupy Tamar’ or OC must be fully democratic and inclusive, allowing the broadest layers of the working population and youth not just to participate like ‘movie extras’ without a voice, but to discuss and shape its direction, demands and tactics through democratic channels. Any negotiations with the government should be open and their recommendations subject to agreement by mass assemblies with the right of different groups to argue for or against.

The ‘Citywide School Strike Campaign’, which young Socialist Action members actively took part in, was heavily criticised by some of the organisers at Tamar because it raised the need for basic democratic ‘ground rules’ such as the right of all groups opposing national education to be able to distribute material, collect funds (in this case to print over 50,000 leaflets for a school strike – something Scholarism refused to do), and collect names on petitions. Our comrades campaigning for a strike were attacked, sometimes violently, and accused in CCP-style language of ‘splitting’ the unity of the movement, ‘trying to hi-jack’, and of masquerading as Scholarism (an organisation that opposed a school strike!). As we countered at that time, the idea that mass struggles should be run like a ‘one-party state’, without dissension or alternative viewpoints, is preposterous and dangerous. This lack of democracy within the movement flowed from the wishes of a ‘small circle’ leadership to keep tight control, prevent the movement from escalating, and depoliticise it. Specifically the organising group sought to dampen growing calls for a school strike and demands for CY’s resignation. They ran the occupation in such a way as to dissolve politics into concerts and poetry readings, before calling it off so suddenly that many activists were left stunned and confused.

Should the movement be non-violent?

Most people prefer to achieve political change without violence, an understandable attitude. Socialist magazine has no truck with the demagogic stand of Hong Kong autonomy advocate Chin Wan, who among other things has said that the democracy struggle must be ‘brave and violent’. We stand for well-organised, disciplined and peaceful mass protests, but we also warn about the serious threat of state repression and the need to prepare politically. No ruling group has ever surrendered its power and privileges without a fight, and this has invariably meant using the state – police, security forces and law courts – as a weapon against the masses. The CCP dictatorship prefers repression in Hong Kong to be ‘outsourced’ through the local police force. But it has been revealed, by Henry Tang Ying-yen among others, that during the 2003 political crisis over Article 23 some sections of the Hong Kong elite also discussed using the PLA garrison in Hong Kong against the protests.

While this has so far not happened in Hong Kong, there is a clear trend toward more repressive policing, including an 8-fold increase in political arrests and harsher prison sentences for a variety of essentially peaceful political ‘offences’. Yet as even Superintendent Stephen Cheng Se-lim, the regional police commander of Kowloon West admitted: “There was no data to suggest protests in recent years were more violent” [South China Morning Post, 16 September 2011].

The pan democratic leaders supporting OC have stressed ‘non-violence’ as if this is a new approach, somehow at odds with other mass protests such as July 1 or the movement against national education. They support Tai’s call for specific measures to keep out ‘violent’ protesters including a selection process and oath-taking ceremony. This gives a totally distorted and misleading picture of political protests. Unfortunately, the same pan democratic spokespeople fail to warn about the sinister build-up of repressive weaponry by the police, including not just 10,000 anti-riot grenades, but also ‘torture’ devices that emit sounds louder than the human threshold of pain.

Clearly it is wrong to say, as professor Tai and some pan democratic leaders have, that protesters should meekly accept arrest. Logically, this means ceding to the government and the police the decision on when to end the mass occupation. In that case, why start it in the first place? Such ideas are put about by people who do not base anything on actual experience – of mass struggle. See for example how the protesting youth in Tiananmen Square organised basic security patrols and even for a time took over the duties of the traffic police (the crime rate actually fell in Beijing in April-May 1989). More recently, the mass uprising at Wukan in Guangdong showed how a well-organised community could stand up to vicious police repression, arrange basic self-defence including expelling the CCP officials and security forces, and eventually force a well-armed dictatorship to offer concessions rather than risk a politically costly attack on the village.

A serious strategy for the looming democracy showdown in Hong Kong must warn about police repression, thereby raising the political risks for the government in ordering a crackdown. At the same time the movement must also organise elementary stewarding and self-defence (against pro-government provocateurs), modelled on the role of pickets in a strike. Rather than increasing the risk of violence, these measures would reduce it. A head-in-the-sand attitude that keeps silent about police repression only emboldens the pro-government camp to attack the movement and increases the danger of flare-ups.

Why are strikes a more effective method than demonstrations and occupations?

In conclusion, if it is viewed as part of a much wider, more far-reaching strategy against the CCP, a mass occupation could play an important role – to rally the forces for an escalation of the struggle. But an occupation alone is not enough given the nature of the Chinese dictatorship. Other methods of struggle, especially the call for at least an initial one-day ‘warning strike’ of all Hong Kong workers, are more in line with the scale of this historic task. A strike should present a series of demands for full democratic rights, linking this to workers’ long ignored calls for improved wages, an 8-hour workday, collective bargaining rights and a universal pension system.

Socialist Action has also advocated student and school student strikes as a vanguard action – echoing the epic 1989 struggle against autocracy. Student strikes and campus occupations can show an example of struggle to be followed by the stronger and more decisive forces of the working class. In the struggle against despotic regimes in Egypt and Tunisia, the beginning of mass workers’ strikes provided the ‘tipping point’. Unlike the pan democratic leaders who do not base their strategies on any concrete experience (and shrink from real struggle), we socialists base our ideas on closely studying these earlier examples of mass struggle and revolutionary overturns. This is to apply this experience when new struggles erupt, to develop the ideas, slogans and tactical methods that can bring success.