China has 60 million left-behind children – where is their ‘China Dream’?

Dahu, chinaworker.info

Wang Fuman, from a poor village in Yunnan province, has become an internet sensation as “Frost Boy” after pictures appeared online showing him arrive at school with crimson cheeks and icy hair. Wang has to walk a nine kilometre round-trip every day to attend primary school. On the day he was photographed by his schoolteacher, the pictures that went viral on social media, the temperature outdoors was minus 9C.

Wang’s plight is not exceptional and the case has understandably triggered a heated discussion on poverty in China, especially rural poverty. The Chinese regime and its vast machinery of media control have injected their own spin into the story, even hailing little Wang as a symbol of “the great effort and strength of the Chinese nation”. The government is doing its best to overcome inherited social problems, they tell us, when in fact it is their own pro-capitalist agenda that has created extreme wealth inequality and condemned much of rural China to stagnation and backwardness.

Government cutbacks closed three quarters of all rural primary schools – over 300,000 – between 2000 and 2015. Local governments, which shoulder 60 percent of education spending, prefer to save money on education and instead divert funds into property deals and infrastructure projects, which push up local GDP and at the same time enrich local capitalist elites and officials. This is the logic of capitalism, for the rich to get even richer, and cannot be reduced solely to the actions of corrupt local administrations, even though that is also undoubtedly true.

Mass school closures

As village schools have disappeared, children are forced to travel longer distances or enrol in boarding schools. This has generated new problems such as overcrowded and unsafe school buses, higher expenses leading to a higher school dropout rate, and also the new boom industry for rural boarding schools. These boarding schools are often dirty, overcrowded and “Dickensian” according to a report by Bloomberg News (6 April 2015). “Hunger and loneliness are commonplace,” it reported. On average pupils at rural boarding schools are three centimetres shorter than non-boarders.

Despite a law stipulating nine years of free education, in practice this does not apply for many rural children. Fewer than half complete their high school education, compared with 90 percent in China’s cities.

Schoolteachers in China have staged hundreds of strikes in the past 4-5 years over low pay, unpaid wages and pension entitlements. “Some of the largest, best organised and most determined worker protests in China in recent years have been staged by teachers,” noted a report by China Labour Bulletin, a Hong Kong-based NGO. Of course, as for other groups in China, teachers are not allowed by law to form genuine trade unions.

Shockingly low wages and pensions has led to an exodus of teachers from rural schools. This is another factor fuelling the mass school closure programme of the past fifteen years. There are numerous cases where too many students are crowded into a school and classroom without enough teachers and resources.

Profit-driven austerity policies and underfunding have thus left rural education in a state of crisis. China’s central government has a longstanding target, since the 1990s, to spend at least 4 percent of GDP on education (the global average is 4.8 percent), but many provinces and local governments still fall short of this level.

Left-behind children

“Frost Boy” Wang is one of more than 60 million left-behind children in China – the term for rural children whose parents are forced to migrate for work to the wealthier cities, sometimes thousands of kilometres away, returning to see their children only once or twice a year. These children are raised by relatives or neighbours or placed in boarding schools. In some cases there are no adults to take care of them. Where is Xi Jinping’s ‘China Dream’ for children like these?

A 2014 study by the Heilongjiang provincial government found that almost half of “left-behind” children suffer depression and anxiety, compared with 30 percent of their urban counterparts. Studies by NGOs in Shaanxi province have found that physical ailments including malnutrition, intestinal parasites and anaemia are rife, concluding that many rural children are “too sick to study”. These illnesses, a direct result of poverty, can inflict irreversible damage to the brains and intelligence of children.

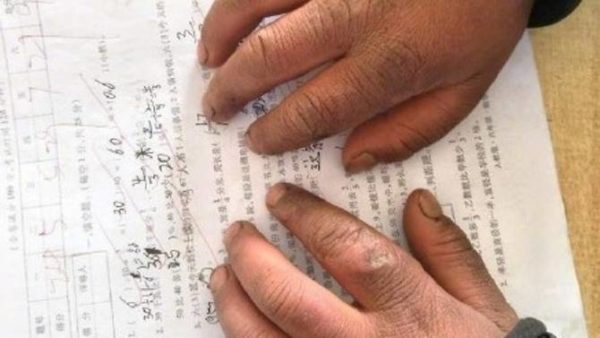

Many rural communities have almost no working age adults left; they have all migrated to the cities. This leaves only the elderly and children behind to shoulder the burden of farming. Wang Fuman’s teacher also posted photos of his calloused hands, worn from working on the land to help his grandmother.

The hardship and emotional trauma of left-behind children contrasts sharply with how the offspring of China’s super-rich elite live, including the children of ‘Communist’ officials. These privileged youth are likely to be sent to foreign schools and universities to get the “best” education, notwithstanding the strident anti-Westernism of the regime’s public propaganda.

Wang Sicong, for example, son of billionaire property tycoon Wang Jianlin, spent his studies exclusively overseas, from elementary school to university. According to a report in Foreign Policy magazine (6 February, 2017) more than 80 percent of government officials from municipal level and upwards send their children abroad to study.

280 million migrant workers

The plight of children like Wang is the cruel downside of China’s so-called economic miracle, which is built on the blood, sweat and tears of more than 280 million super-exploited migrants from the country’s poor interior. Migrants make up one in three of China’s workforce. The hukou system, which assigns a lifelong ‘rural’ or ‘urban’ status to all children at birth, has been a key mechanism for segregating and subjecting migrant labour to the rawest forms of exploitation.

Migrants are with very few exceptions not entitled to permanent status in the cities where they work, even after living there for decades in some cases. They are not entitled to send their children to city schools. They are blocked from the housing market in the cities where they work, and which anyway they cannot afford given extreme high prices/low wages. In 2014, only 16.4 percent of migrants from other provinces had a pension and just 18.2 percent had medical insurance, according to China’s National Bureau of Statistics (this is the last year for which data is available).

The breakneck economic development of China has created one of the world’s most extreme wealth gaps. China today has 36 percent of the world’s dollar billionaires, more than any other country including the US. At the same time a study by Peking University found that the poorest 25 percent of Chinese households (more than 340 million people) own just one percent of the country’s total wealth.

Poverty is particularly prevalent in the countryside, which is still home to 43 percent of the population (590 million of 1.3 billion people), but also exists in cities and especially in many of the new towns that feature in the government’s ongoing urbanisation programme. The government plans to shift 100 million people out of rural areas by 2020, on the premise that city dwellers have a higher per capita income than their rural counterparts.

But in many cases the urbanisation drive has uprooted poor farmers who somehow could survive on what they could grow, and shunted them to new town projects where prices are much higher but a viable local economy is non-existent. What awaits these relocated families is often unemployment or precarious employment. They have exchanged one form of poverty (rural) for another (urban).

The major driver of the regime’s urbanisation programme is the need to fill dozens of ghost towns that have sprung up under the frenzied building and infrastructure boom of the past decade, and thereby prevent a collapse of the housing market. It is not primarily driven by concerns to improve the lives of the poor.

At the 19th Congress of the ‘Communist’ (CCP) dictatorship, held in October, president Xi Jinping highlighted anti-poverty policies as a key plank of his next five-year term and his ‘China Dream’ mantra. He promised to wipe out poverty by 2021 when the CCP will celebrate its 100th anniversary. The regime boasts impressive, but questionable figures, to show its achievements in this field. According to official statistics there are only 43 million Chinese living below the government’s poverty line, but this is set at the extremely low level of 2,300 yuan (US$350) per year.

This has been mocked by some critics as “digital anti-poverty” – by moving the poverty line around the government can of course achieve wondrous propaganda results, but this has nothing to do with changing the economic conditions for tens of millions of poor families.

War on the “low-end population”

Last November, a deadly fire in a migrant district of Beijing was seized upon by the capital’s government to begin mass evictions and demolitions of migrant living quarters in the name of “fire safety”. Tens of thousands were told to leave Beijing and dumped on the streets at short notice, in freezing weather, with no alternative accommodation, compensation or other support provided. Many lost their belongings in this forced clear-out, with police using bulldozers and heavy machinery and even threatening those NGOs and volunteer groups that tried to help provide food and shelter to the evictees. This huge campaign of ‘social cleansing’ carried out with brutal methods generated an enormous backlash on social media. That the government and media claimed these measures were aimed at the “low-end population” – hardly Communist terminology (!) – added to the storm of criticism.

The mass evictions in Beijing, with similar if smaller operations in other cities, are part of strategy to clear older, poorer districts for redevelopment and gentrification, putting even more profits in the hands of the property companies and increasing government revenues.

Migrants gravitate to these districts with their overcrowded, unsafe and tiny living spaces as the only affordable places in expensive cities like Beijing. Housing costs in the capital are now among the highest in the world. The war on the “low-end population” showed the city authorities in their true light: arrogant, greedy, and full of class contempt for the poor.

The government is pledged to reform the hukou system, but rather than scrapping it they are introducing a ‘hukou 2.0’ – involving modifications but maintaining a system of legal controls on the movement of the poor. Under the reforms, less developed and less attractive ‘tier 3 and 4’ cities will have their hukou restrictions relaxed to soak up a certain influx from the countryside, but migration controls for the wealthiest ‘tier 1 and 2’ cities will be tightened putting them off limits to the “low-end population”.

The case of little Wang has triggered another intense debate on social media. The regime and its propaganda machine have tried to control the story with state media focusing on reports of charitable donations to Wang’s family, his school and his classmates. One businessman has even offered Wang’s father, a migrant construction worker, a job closer to home so that he can live with Wang and his sister.

State-owned companies and the Communist Youth League (a wealthy state institution and not in any way an actual ‘youth league’) have made well-publicised donations of money, winter clothing and heating equipment. Thousands of individuals all over China have been moved by Wang’s story to make generous individual donations, with more than 2.2 million yuan collected.

‘Charitable’ donations

This may reflect the kind-heartedness of Chinese people, but charity is not the answer to the scourge of poverty. Poverty is part of the system, and the system can only be changed by mass political action. And it is questionable how many donations will actually reach Wang’s family or really be used to alleviate poverty.

Government agencies and companies have been quick to ride on the wave of charitable sentiment aroused by Wang’s case. This has allowed them to win some cheap PR. For wealthy state institutions like the Communist Youth League the donations to Wang’s school are peanuts, and a bargain in terms of the publicity they generate. These funds are public money and should be ploughed into education and other services as a right, not as acts of ‘benevolence’. In so doing, the government hopes to hide its role in dictating the very anti-working class policies that have made the poor poorer and the rich richer. These include the wholesale squandering of public funds on white elephant infrastructure projects, often in favour of crony capitalists.

The government and its various arms are offering ‘charity’ but this is a drop in the ocean compared to the vast scale of poverty in China. Instead, working people have a right to demand proper funding for the school system, higher pay for teachers, an end to school closures and a huge programme to boost rural infrastructure under the democratic control of the people themselves.

The terrible exploitation of migrant labour and the scourge of 60 million left-behind children must be brought to an end. This requires the immediate abolition of the hukou system and massive increases in government expenditure on healthcare, education and pensions to create equal and modern welfare and public services for all citizens. At the same time heavy taxes should be levied on the tycoon class and super-rich, also requisitioning the millions of empty houses in China’s cities to be used for public needs.

Socialist policies, to put the economy under the democratic control of the working class and end capitalist exploitation, are the only way to eradicate poverty.