Capitalists commentators applaud ‘Liconomics’ but its effects on the global economy can be disastrous

chinaworker.info

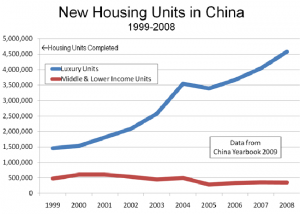

“China has basically said goodbye to 8 percent GDP growth,” declared Ha Jiming, a spokesman for Goldman Sachs in China, recently. The bank’s June research report went on to predict “average annual growth rate in the next seven years to 2020 perhaps falling to the vicinity of 6 percent”. While this economic growth rate remains impressive (if official figures are to be believed) by comparison with the sickly performance of most advanced capitalist economies, China’s economy has left the fast lane. Even if growth of seven-plus percent holds in coming years – which many are now questioning – the Chinese economy has already entered a serious crisis. Soaring debt levels and an uncontrolled ‘shadow banking’ credit surge are cancelling out the central government’s efforts to steer economic policy. Unprecedented levels of industrial overcapacity and over-construction point to a painful economic ‘correction’ and possible ‘hard landing’ in the coming period. This is the background to the “painful economic restructuring” Premier Li Keqiang is promising.

“Frankenstein economy”

Many commentators say China’s economy is turning into a Frankenstein monster: “It’s a giant and powerful creature born of unorthodox experiments, and its makers are increasingly losing control,” said Bloomberg. One could say the same about the US and European economies, and the new leaders’ pro-capitalist policies do not offer a solution. But the explosion of debt throughout the Chinese economy since the onset of the global capitalist crisis, starting with the regime’s 2008 stimulus package, is unprecedented for any large economy. Overall credit jumped from US$9 trillion to US$23 trillion in 2008-12. “They have replicated the entire US commercial banking system in five years,” says Fitch’s senior director in Beijing, Charlene Chu.

An increasing number of commentators compare the signs of financial stress in China today to the situation in the US just prior to its banking meltdown. “We believe that the domestic Chinese banking system is a mess, with an enormous amount of bad loans, or loans waiting to go bad. The problems of China’s lenders are greater than those of Western banks on the eve of the financial crisis,” warned Carson Block, of Muddy Waters Research, a company which has exposed several accounting scandals in Chinese companies.

The growth of shadow banking in China, which accounted for 50 percent of new credit last year, is of particular concern. Not only does its sheer scale present daunting problems for Xi and the new CCP leadership, just seven months into their term, but the fact that most shadow banking actually occurs through ‘moonlighting’ on the part of the mainstream banks, shows the Chinese dictatorship has lost control over its banking system. This reflects a growing ‘financialisation’ of the economy with new credit increasingly ploughed into speculation or recycling old loans rather than into productive investment.

The rationale for this was explained by the deputy general manager of a state-owned steelmaker, who spoke anonymously to Reuters: “Can we use the money to expand production? Definitely not. We will lose more if we produce more. We can only rely on other channels.” His steel firm was losing an average 100-200 yuan per tonne of steel sold, he explained, and had therefore turned to lending money through ‘entrusted loans’, one of the many categories of shadow financing. There are many other instances of non-financial state-owned enterprises (SOEs) engaging in shadow banking.

Lowest growth for 23 years?

Last year’s GDP growth of 7.7 percent was the lowest for 13 years. 2013 could see the slowest growth for 23 years, if as many now think, the government misses its GDP target of 7.5 percent. At a recent meeting of provincial government heads, Xi said, “We should no longer call someone a hero simply based on the GDP growth rate,” signalling his administration’s emphasis on curbing runaway credit and massive, increasingly wasteful investments. Changing direction will be no easy task, however, given the risks of burst financial bubbles, a banking crisis, or of a credit-squeeze-induced hard landing.

Vice Minister of Finance Zhu Guangyao has admitted the central government does not know how much debt local governments have amassed, warning previously published estimates are too low. A 2010 government report put local government debt at 10.7 trillion yuan, around 25 percent of GDP at that time. Yet according to Xiang Huaicheng, a former finance minister, this debt is now likely to exceed 20 trillion yuan (US$3.3 trillion). But there has been no publication of complete data since 2010, with the government evidently fearing a true picture would demolish the façade built up by China’s banks – now among the world’s biggest – of supposedly healthy balance sheets and extremely low non-performing loan ratios.

From ‘gradualism’ to ‘shock therapy’?

Premier Li Keqiang’s economic agenda, nicknamed ‘Liconomics’, amounts to ‘painful’ restructuring of the banks and state-owned sector in order to achieve sustainable i.e. slower GDP growth, by weaning the economy away from unprecedented amounts of debt, towards more consumption and private investment. “It is a self-imposed revolution that will require real sacrifice, and it will be painful,” he told the world’s press in his first appearance as premier last March. This is a theme the state-run media have repeated ad nauseum. At the time of June’s credit squeeze, Xinhua News Agency commented, “For the blessing of a more sustainable economy, banks are the first, but certainly not the last to suffer the hardship.”

Li’s economic team is dominated by former lieutenants of Zhu Rongji, hailed by capitalists internationally as the most ‘reform-minded’ of China’s premiers, whose ‘merits’ include destroying 60 million SOE jobs. Former Zhu acolytes seconded to Li’s team include Vice Premier Ma Kai, Finance Minister Lou Jiwei and central bank governor Zhou Xiaochuan. Ma and Zhou are princelings.

Li’s policies, if fully implemented, amount to a form of deflationary ‘shock therapy’ to shake-up an economy that – run on a capitalist ‘market’ praxis – is fast running out of other options. This ‘shock therapy’ is not motivated by ideology – the new CCP bosses are ‘pragmatists’ – and it aims to target key state-dominated sectors especially the financial sector, rather than apply wholesale across the economy. Its aim is to break the current addiction of state-owned entities to credit, and the concomitant build-up of idle capacity, by subjecting these sectors to greater ‘market forces’ through private investments. But this is a high-risk approach, which is already facing major problems. One immediate effect of ‘Liconomics’ is likely to be a further credit drought as real lending costs (in defiance of official rates) head upwards, something that could turn the government’s hopes of a ‘controlled’ slowdown into a full-blown recession, or worse, if a shortage of credit triggers the bursting of China’s multiple asset bubbles. In such a situation the government’s refusal to inject new stimulus could be put to an early test.

Capitalist commentators (who have learnt nothing from the global crisis) applaud the new CCP leadership’s ‘bold’ beginnings, seeing this as the only way to shift China onto a sustainable growth trajectory. But as the saying goes one should be careful what one wishes for. The effects of Li’s planned reforms on global GDP will mostly be negative. China has been the main motor behind the last decade’s ‘commodities supercycle’ of record energy and mineral prices (boosting growth particularly in Africa and Latin America). China is also the number one trading partner of 124 countries, knocking the US into second place with a score of 76 countries. A much slower pace of Chinese growth will be felt throughout the global economy, amplifying the problems of capitalism on a world scale. “Is the world ready for Beijing’s economic new normal?” wondered economist Stephen Roach, a keen supporter of ‘Liconomics’.

Princelings and the CCP

The 18th Congress (last November) produced the closest thing to a ‘power shift’ at the top of the one-party dictatorship. The CCP is sometimes called ‘one party, two coalitions’ – referring to the elite princeling faction (taizidang) and the plebeian Youth League faction (tuanpai). The princelings, from billionaire ‘red’ families, captured a majority of top posts within the dictatorship for the first time. This signalled a number of things, borne out of a fear of the future and a rejection of political change. By embracing a neo-dynastic succession, the ruling elite hopes to protect their fabulous riches – derived from plundering state resources – by ensuring the continuation of one-party dictatorship. Xi’s family wealth is estimated at US$376 million; three times the wealth of the entire British government (with 17 millionaires). Other top princelings have amassed even more impressive fortunes. Like the corrupt cliques of ousted Middle Eastern dictators, the princelings know they are finished if the one-party dictatorship goes down. Their mission is to save it at all costs.

Xi is a top princeling, but rather than a mere tool of the princeling faction he is trying to build his own power base, balancing between the factions and striking deals with one then the other. This balancing act also seeks to contain entrenched factional rivalries that could threaten an open split. Outwardly, Xi’s manoeuvrings reinforce the regime’s schizophrenic features, whereby one policy appears to contradict another. Increased nationalism, and muscular interventions over disputed territories at sea, are apparently negated by conciliatory gestures from Beijing to the US and South East Asian countries (but not so far to Japan) to seek a ‘common’ solution. While rapidly upgrading its military, boosting its role in Africa (sending combat troops to Mali, its fourth African UN intervention), and Latin America, the CCP wants to avoid a direct conflict with the US – as shown by its stand over ex-NSA man Edward Snowden.

Xi’s ‘Maoist turn’ is the most glaring of these contradictory policies: peppering speeches with Mao quotes and borrowing to some extent from the style of the jailed Bo Xilai. There is nothing radical or remotely anti-capitalist in this. Mao’s spectre is being used to crackdown on dissent – including within the state apparatus – and especially to suppress calls for democratisation (so-called political reform) and its latest incarnation in the debate over ‘constitutionalism’. Like Deng Xiaoping, Xi has learned to ‘signal left and turn right’. He and Premier Li plan to launch a major package of pro-capitalist economic ‘restructuring’ at the autumn Central Committee plenum, likely to include financial sector deregulation, opening up of some state monopoly sectors, and privatisation, perhaps sugared with populist measures such as a reform the apartheid-like ‘hukou’ residential pass system (but if so, limited and gradual in scope), and a possible partial relaxation of the one-child policy.

No ‘democratisation’

The Xi-Li leadership seeks to bolster authoritarian rule and at the same time win back public support with a selective and largely symbolic crackdown on corruption and “hedonism” alongside increased nationalist rhetoric. But it rejects political reform fearing that even limited democratisation risks a political meltdown, emboldening mass challenges and collapsing the ‘self-discipline’ of the CCP-state over its antagonistic components. Events in Turkey, Brazil and Egypt will have reinforced Xi’s resolve against political reform. The ousting of Mursi in Egypt prompted a stream of articles in the regime-controlled media, such as People’s Daily and Global Times, stressing social stability and warning against “Western-style ‘one man, one vote’ democracy.”

“A lesson provided by Egypt to the Chinese leadership is that they have to fully grab power,” said political commentator Zhang Lifan. “The economy is facing a downturn now and Beijing leaders will find it more urgent to maintain stability. Any loss of power may make them collapse.” This is nothing new, it merely reinforces the outlook of the Xi-Li leadership. Xi is “obsessed with the Gorbachev phenomenon and doesn’t want to be remembered in history as the Gorbachev of China,” says China watcher, Roderick MacFarquhar.

Mass struggle: a learning curve

There are a continuing high number of mass struggles, but these remain decentralised. There were 180,000 land-related protests in 2012, alongside countless strikes. In Wukan, where a landmark struggle broke out in 2011, the rebels-turned-village-leaders have become split and increasingly criticised for failing the movement’s demands for the return of stolen land. Wukan is unquestionably a very important struggle, because of the degree of democratic self-organisation acheived by the villagers during their mass struggle, which unfortunately they agreed to dissolve in return for a December 2011 deal with provincial CCP leaders. The idea that this signalled a new ‘reformist’ approach to conflicts on the part of the dictatorship has been shown to be false, with increasing repression alongside largely empty concessions that “bounce like a fake cheque” as has happened in Wukan. This harsh experience is nevertheless educating a layer of land activists and others to distrust all levels of the CCP.

100 Beijing workers at a medical supply factory made world news when they took a US capitalist hostage in June over unpaid severance payments. This tactic is becoming increasingly common as shown by a similar action in Huizhou, southern China, with five Chinese managers (of Shanghai Zhongji Pile Industry) detained for five days over non-payment of wage arrears.

Reflecting the downturn in the economy, a wave of outsourcing, company closures and relocations (including to even lower-wage economies such as Bangladesh and Cambodia), most strikes are defensive – to press for unpaid wages, bonuses or compensation tied to closures and relocation. Figures from the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security for 2012 show 6.2 million workers filed complaints to the authorities related to 20 billion yuan (US$3.2 billion) in unpaid wages. This may just be the tip of the iceberg.

Workers face major new challenges as the economy slows. The new government is making no secret it plans to inflict ‘painful’ policies. While Xi and Li will try to sugar this pill with some populist promises to expand welfare provision (we’ve heard this before) and reform the hukousystem (ditto), the regime has no alternative from its class standpoint but to launch a fresh wave of attacks on the working class and the poor to pay for the speculative binge of the CCP authorities and their capitalist cohorts. Highly indebeted local governments, which account for over 80 percent of all government spending, are hardly in a position to finance an expansion of welfare or the inclusion of migrant workers (hukou reform). As on so many other occasions, local governments will do their utmost to evade and ignore new social spending commitments imposed from Beijing.

These contradictions are preparing the way for explosive mass resistance in the coming period. New internal crises and economic shocks can cause paralysis within the regime and create openings the working class can exploit to win concessions and organise itself. The building of workers’ organisations, initially underground, and a genuine socialist party is vital to organise the struggle against capitalist crisis and dictatorial rule.