Anger from below, manoeuvres from the top

CWI

Algeria’s 50-year governing party, the National Liberation Front (FLN), has strengthened its rule in the parliamentary elections on May 10 – probably the last to take place under the ailing, frail 75-year-old president, Abdelaziz Bouteflika. The FLN increased its seats in the newly expanded parliament, from 136 out of 389 to 220 out of 462 (47.61 percent of the vote).

The FLN’s ally and main support, the National Rally for Democracy (RND) of prime minister Ahmed Ouyahia, a party close to the military and loyal to Bouteflika, won 14.71 percent and 68 seats. This gives these two parties a comfortable parliamentary majority.

The three-party bloc of Islamists, the Green Algeria Alliance, did not achieve the electoral breakthrough that some analysts were predicting, getting only 48 seats, 10.38 percent. The results came as a big blow to these parties, which had long expected a victory and had the ambition of becoming the leading political force in the country – echoing the so-called “green wave” of electoral breakthrough by Muslim Brotherhood-influenced parties in other countries in the region.

The elections, presented by the notoriously corrupt Algerian regime – known for its long-standing tradition of chronically-rigged elections – as “the freest in 20 years”, have been praised by all western countries. U.S. and EU officials rushed to congratulate this “new step towards democratic reform”.

This was to be expected, of course. The Algerian military is an essential ally of U.S. imperialism in its “war on terrorism” in the Sahel region. One fifth of Europe’s gas revenues come from Algeria and, recently, the IMF asked for Algeria to help bolster its gas and oil resources in preparation for any further bailouts in Europe.

Fraudulent elections?

The poor showing of the religious bloc surprised some commentators. The leaders of the Green Algeria Alliance have denounced the results as a massive fraud. Aboudjerra Soltani, president of the coalition’s leading group, the MSP (Movement of Society for Peace), called them “neither acceptable, logical, [n]or reasonable”.

However, unlike countries such as Egypt and Tunisia, the parties in the Green Algeria Alliance, MSP in particular, are directly associated to the mafia regime in power. The MSP has been closely working with the regime for many years and has been part of the presidential alliance with the FLN and RND until recently. Four of its leading members were ministers in the outgoing coalition government. His party decided at the last minute to go over to the opposition, trying to benefit opportunistically from the electoral trends manifested in other North African countries.

Also, some may have been scared away from voting for religion-based parties because they remembered the bloody tragedy of the 1990s civil war, into which Algeria was plunged when the army cancelled the 1991 parliamentary elections after the FIS (Islamic Front of Salvation) won the first round. This would be particularly true for an older layer still profoundly affected by this violent period.

That is not to say that fraud and electoral manipulation did not happen. The huge increase in votes for the FLN is suspicious to say the least. And the fact that initial results were announced by the interior ministry before many important regions (such as Algiers, Oran, Mostaganem, Bejaia) had fully completed the vote-counting operation is just one example of a dirty electoral process that Algerian people have learnt not to trust.

Important abstention

Even according to official figures, however, fewer than half the potential voters made their way to the polling stations. Nearly one out of every five ballots cast was blank or spoiled. In the major urban areas – and in the region of Kabylie, a historic hotbed of popular resistance – the turnout was particularly weak. The capital, Algiers, registered 30.95 percent participation; Tizi Ouzou, the main Berber city in Kabylie, just 19.84 percent. The youth, especially, abstained en masse.

Overall, the interior ministry claims 43 percent turnout, up from 35 percent in the 2007 elections, and minister Daho Ould Kablia declared these results “remarkable”, saying they confirmed Algeria’s “democratic credentials”.

Compared to previous elections, and to predictions made before the polls, the turn out was indeed higher than expected. However, these official figures are met with strong scepticism, if not derision, by most Algerian people and independent commentators. Many allege that fraud was used to boost the participation figures. Accusations include: stuffing ballot boxes, bussing in fake voters, eliminating abstaining voters from the lists in order to artificially inflate the figures of turnout, and other similar practices.

Mass distrust

Some opposition activists put the real figures of participation below 20 percent. This is difficult to verify, but would not be surprising. A general atmosphere of contempt, apathy, and disinterest in the elections has been reported, illustrated by deserted polling stations.

Disillusion and anger at the corrupt political caste were particularly symbolised by the state of the electoral hoardings set up to display the lists and candidates. These were often destroyed, uprooted, burnt down, or tagged. According to the Algeria news website, DNA: “Across the country, citizens wrote tags calling to boycott the elections, made fun of the candidates, party officials and ministers, describing them as ‘thieves’, ‘corrupt’ and ‘sold’… In many cities, villages and neighbourhoods, the hoardings have become the spots of free public expression to denounce the excessive price of potatoes, demanding visas, housing, roads or to caricature the leading politicians.”

Intimidation, harassment and repression

These elections were conducted under the official slogan, “Algeria is our spring”. A massive propaganda campaign was undertaken to push people to vote and give some credibility to the results. Imams in the mosques have been used for weeks to call on Algerians to vote en masse. Text messages have been sent to every Algerian’s mobile for the same purpose.

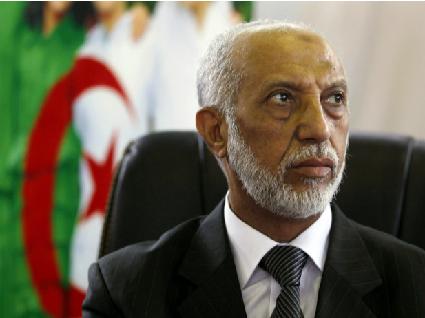

This anti-abstention campaign also took the form of spreading fear, warning of terrible consequences if people did not go to the polling stations. For weeks, leading politicians have been arguing that the choice was basically between the ballot box and opening the door to insecurity and chaos. Bouteflika compared the historic importance of these elections to the anti-colonial war of the 1950s. The general secretary of the FLN, Abdelaziz Belkhadem, warned Algerians of a foreign invasion if they did not vote.

Also, the authorities resorted to numerous arrests, among other tactics, to prevent people from demonstrating in the capital in the run-up to the elections. While the election was presented as evidence of a “process of democratic opening”, the pre-election period has been marked by a surge of attacks on democratic rights. Activists caught participating in a gathering are automatically subject to a day in police custody. Despite the official lifting of the state of emergency in February of last year, a climate of harassment of opponents and a ban on public protest and meetings continues to be the norm.

The prominent case of Tarek Mameri, a 23-year-old unemployed activist from Algiers, reveals the methods the regime has been using to silence dissenting voices. He was kidnapped on May 1 and held arbitrarily by the police for several days. He was accused of circulating videos on social networks calling for a boycott of the elections.

Is Algeria an “exception”?

On the surface, Algeria seems to be one of the countries least affected by the “Arab spring”, and tends to be characterised as an exception in a region hit by mass movements, uprisings, and revolutionary features. Among other things, Algerian people remain traumatised by the “black decade” of the 1990s. The opening chapter of this period was the country’s own aborted “spring” of October 1988: a mass youth and workers’ revolt drowned in blood by the army and security services.

The first pluralistic elections, held in 1991, led to the victory of the radical FIS, the main beneficiary of the anger at the corrupt ruling party and its military backers. Fearing it was losing control, the army cancelled the elections, launching the country into a spiral of violence and counter-violence. The horrors and brutality of the army and the armed fundamentalist groups mirrored each other. Between 100,000 and 200,000 people were killed and over half a million Algerians fled the country.

Like its counterparts in the region, today’s Algeria combines a similarly explosive mixture of mass youth unemployment, housing crisis, rising living costs, generalised state-level corruption, police brutality, and the concentration of wealth in the hands of a tiny corrupt elite strongly associated with the political establishment.

A tragic expression of the deep social crisis is the increased number of self-immolations, which have mounted to several dozen in the past year. According to a recent poll published by the El Watan newspaper, only 18 percent of Algerians are satisfied with their life, 6 percent are “enthusiastic” about the way the economy is run, and 26 percent would like to emigrate abroad for a better life.

Meanwhile, there is growing infighting at the top of society, an intensified internal power struggle at the highest levels of the state that involves conflict between civilian and military power centres. There is an ongoing battle on economic orientation between neo-liberals, who want to further open up the country to foreign investment and international companies, and economic “nationalists”, who benefit significantly from the lucrative state-owned oil and gas company, Sonatrach. There is also a battle fragmenting the FLN ranks, which has increasingly been on public display.

After a wave of youth riots all over the country in January 2011, echoing the neighbouring Tunisian uprising, Bouteflika announced a series of window-dressed political reforms and economic measures. Fearing the threat of mass unrest and political shockwaves, the regime used the massive oil revenues – an estimated $181 billion in cash reserves at the end of last year – to try and buy social peace. This included the distribution of 242,000 housing units during the year, subsidies on consumer goods, a rise in public-sector wages, and the provision of free school material for thousands of families.

In spite of these measures, the social situation remains explosive. “At any moment, the Algerian case can burst out”, commented Noureddine Hakiki, an analyst at Algiers University. Despite the country’s massive hydrocarbon wealth, dissatisfaction is widespread, and there are frequent demonstrations, strikes, and riots over unemployment, poor utilities and lack of housing. For years, militant labour disputes and popular protests have been part of the daily landscape. These have been pushed to become even larger and more frequent since last year’s revolutionary developments in the rest of the region.

The national security services registered a record 10,910 interventions in 2011 to maintain “public order”, according to El Watan. The report added that “the main origins of these trouble[s] of public order were essentially due to demands of a social and professional character”. Each week brings new examples of local community rebellions, with inhabitants mounting roadblocks or engaging in sit-ins to demand water or gas supplies, jobs, better housing, or other basic needs. Strikes have also increased sharply in the recent period. Even the electoral commission in charge of supervising the May elections went on strike twice.

The growing street protests and strikes show that, despite the terrible shock therapy of the 1990s, a new generation of working-class and youth activists is rising. They are recovering from the defeats of the past and rediscovering the rich militant tradition which has marked Algerian history.