Rising national tensions point to new turbulent era in East Asia

Vincent Kolo presents a view of the Diaoyu Island conflict as a contribution to discussion within the Chinese section of the CWI

The conflict over disputed islands in the East China Sea has triggered the most serious diplomatic crisis between China and Japan, the world’s second and third largest economies, since they normalised relations 40 years ago. Large-scale and sometimes violent anti-Japan protests swept China in September, inflicting heavy economic losses on Japanese-invested companies. Politicians on all sides have engaged in warmongering speeches about defending national sovereignty. This is part of a high stakes battle of political nerves between Beijing and Tokyo, triggered by the decision of Japan’s Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda, under pressure from the country’s shrill far right fringe, to ‘nationalise’ three islands within a disputed island group by purchasing them from their reportedly bankrupt ‘owners’.

Known as the Diaoyus in China and the Senkakus in Japan, these tiny uninhabited islands (covering just 6.3 square kilometres) have been under Japanese “administration” since 1972, but their status under international law is ambiguous. The Chinese regime is incensed that Japan has broken an understanding they reached in the 1970s that the issue of sovereignty over the Diaoyus/Senkakus would be shelved indefinitely. In this spirit, the two countries struck a deal in 2008 to begin joint exploration of the energy resources around the islands. That deal is now moribund.

The islands sit amid rich fishing grounds and possible oil reserves, but the prime driver of today’s conflict is prestige, and the regional ambitions of the Japanese and Chinese ruling elites. The islands occupy a symbolically sensitive position in Sino-Japanese relations because they were first seized by Japan with its victory over the fading Qing dynasty in the Sino-Japanese war of 1895. This war marked the beginning of Japan’s empire-building, with the annexation of Taiwan (Formosa) and later Korea, followed by the invasion of China itself in the 1930s, in which perhaps 20 million Chinese perished. Recent anti-Japan protests in China, and on a lesser scale in Hong Kong and Taiwan, have coincided with politically loaded anniversaries, such as the ‘Mukden Incident’ on September 18, 1931, which marked the beginning of Japan’s occupation of northeastern China (Manchuria).

“The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living,” noted Karl Marx. History exercises an important influence on relations between Asian states because none of the historical problems created by capitalism and imperialism have been solved. The potential to make mischief from history is shown by the campaign of Tokyo’s racist governor Shintaro Ishihara, who first proposed the scheme to buy the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands, thus triggering the current crisis.

Inter-imperialist tensions

The current standoff in the East China Sea, and similar conflicts in the South China Sea over the larger Spratly and Paracel island groups, are part of a much wider geopolitical struggle – a struggle for economic hegemony in Asia between the US, China and Japan, but also involving Russia and India in their respective ‘spheres of influence’, with supporting roles for several other states in the region including Australia, Indonesia, South Korea, the Philippines and Vietnam.

Tensions in the South China Sea also centre on disputed access to fishing grounds, undersea energy deposits, and military-strategic issues such as control of vital trade routes and the ‘right’ of US military vessels to operate in China’s two-hundred-mile exclusive economic zone (EEZ). Beijing, which has declared the whole South China Sea a “core national interest” – placing it on the same level as Taiwan, Tibet and Xinjiang – is in dispute with the governments of the Philippines and Vietnam in particular over some of these islands.

No less than seven governments lay claim to all or some of the Spratly Islands and three in the case of the Paracels. The frequency and sharpness of territorial conflicts has increased in recent years, helping to fuel a militarisation drive by all governments, with ballooning defence budgets (at the expense of urgent social expenditure) and a focus on naval expenditure in particular. A clash over the Scarborough Shoal (Huangyan Island in Chinese) in April this year meant the Philippines and China were “nearly brought to war” in the words of Senator Antonio Trillanes, who was sent to Beijing for secret talks on behalf of Philippines’ President Benigno Aquino.

“We are all gearing up for an international tug of war in this region,” noted Narushige Michishita, a Tokyo-based commentator on security matters. “Whenever the distribution of power changes in a dramatic way, people start to redraw lines.” [New York Times, 22 August 2012]

The centre of economic gravity in the world economy is shifting eastwards, something especially noticeable since the onset of the worldwide capitalist crisis in 2008. According to IMF data, developing Asia (27 states excluding Japan, Australia and other developed economies) has this year overtaken the 17-member Eurozone in economic terms, accounting for 17.9 percent of global GDP, compared with the Eurozone’s 16.9 percent. Ten years ago these Asian countries accounted for just 8 percent and the Eurozone countries 20.8 percent of global GDP – a staggering turnaround.

Under capitalism, just as class divisions have not softened but sharpened during the past two decades of rapid growth, so too have the rivalries between different states. The decline of Japanese capitalism relative to its main competitors, especially China, summarised by two ‘lost decades’ and Japan’s demotion to third-place in the global economy, has introduced a new source of instability into the region. The Japanese ruling class want to remain a leading world power, increasingly looking to a more assertive foreign and military policy, which means shedding the ‘pacifist’ constitution in force since the end of the Second World War. Spearheading these demands are the extreme right leaders of Japan’s three major cities.

US imperialism’s ‘Asia pivot’

Alongside this we have the aggressive push by US imperialism through the Pentagon’s ‘Asian pivot’ to recapture lost ground in the region, pushing back against China’s growing influence after a decade in which the US was distracted by its wars in the Middle East. When the US launched its disastrous invasion of Iraq in 2003, China was the world’s sixth largest economy. By the time the ‘pivot’ was unveiled in 2011, China had become the second largest economy.

The new US strategy will shift 60 percent of US naval power to the Asia-Pacific region by 2020, with new bases and military agreements being established across the region. Newly announced US troop and naval deployments in Australia (in Darwin and Perth), for example, and a bigger US naval presence in Singapore, are to safeguard “freedom of navigation” in the Malacca Straits and South China Sea. The real aim of these deployments is to control strategic oil routes from the Middle East and Africa, which are vital to both China and Japan, in the event of a full-blown conflict. Washington has in effect made common cause with Japan’s right-wing nationalists, urging a bigger Japanese military role as part of the wider US strategy to contain China.

The pull of China’s economy means the Beijing regime now wields formidable ‘soft power’ throughout Asia and globally, in terms of economic and political leverage. But despite Beijing’s double-digit increases in military spending it is still no match for US ‘hard power’ – its huge military superiority. This is especially the case in terms of naval power, despite the rapid Chinese naval build-up of recent years. The London-based International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) estimates that annual US military spending exceeds US$1 trillion, a larger sum than the military spending of the next 42 nations combined. China by comparison spends around US$107 billion annually, which is the second highest in the world.

The American ‘pivot’ and China’s naval build-up are spurring an Asian arms race. The continent’s military spending is poised this year to overtake Europe’s for the first time in modern history, according to IISS. Last year, the Philippines government almost doubled its defence budget to US$2.4 billion. Arms spending by Malaysia jumped eightfold in 2005-09, compared with the previous five years, while Indonesia, another party to the Spratly Islands dispute, increased spending by 84 percent in that period. Governments acquiring or upgrading submarine capabilities include Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. The combined military budgets of Southeast Asian countries increased by 13.5 percent in 2011, to US$24.5 billion. By comparison, just US$8 billion per year would ensure safe drinking water for the Asia-Pacific region, where 500 million people lack access today. This shows the criminal misallocation of resources under capitalism, pouring public money into armaments at the expense of socially urgent investments.

Asia’s rapid economic expansion has raised class contradictions to unbearable levels. This is apparent in China where the regime faces a potentially revolutionary crisis as social discontent reaches explosion point alongside an economy adjusting to the ‘new normal’ of single-digit growth. By the year 2020, almost all of the world’s 20 tallest buildings will be in Asia (nine in China alone) as towering monuments to the vanity of national rulers. Yet 61 percent of the world’s slum dwellers are also in Asia, and half a million Asians die every year from pollution. The Asia-Pacific region now boasts more ‘high net worth’ individuals (i.e. dollar millionaires) than either Europe or North America. Everywhere the wealth gap has widened, with the process of capitalist globalisation eliminating secure jobs in favour of precarious contract work.

Even in Japan, a record 2.1 million people are now receiving state benefits to compensate for low incomes, and the OECD group of wealthy nations recently judged it the sixth most unequal country in its ranks. A region-wide backlash against the effects of capitalist globalisation can be seen in recent massive strikes in Indonesia (against outsourcing and for increases in the minimum wage) and India (against opening the retail sector to multinational companies). As popular opposition mounts governments everywhere are turning to nationalism to divert popular anger away from their own policies.

Asia’s maritime disputes are not new, so why have they erupted with such force at the present time? Governments and nationalist politicians have deliberately seized upon these disputed islands to whip up nationalism for their own gain. South Korea and Japan are at loggerheads over the Dokdo/Takeshima Islands, while Russia and Japan recently squared off over the Southern Kuril Islands, known in Japan as the Northern Territories. Medvedev, the Russian Prime Minister, visited the islands in July, drawing condemnation from Tokyo. Both governments claim these islands as ‘integral’ parts of their territory.

Taiwan, which sits closest geographically to the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands, has also seized upon the current diplomatic crisis to renew its own claim to the islands, which overlaps and competes with Beijing’s (both governments claim the islands for ‘China’ – but disagree on which ‘China’).

In Taiwan as elsewhere there is a domestic agenda behind the military posturing of president Ma Ying-jeou and his Kuomintang (Nationalist Party) government, which is increasingly split over the Diaoyu issue. Ma, whose popularity has slumped to 15 percent in recent polls, denounced Japan’s nationalisation of the islands and sent naval vessels into the disputed waters – engaging in a full-blown water fight (!) with the Japanese coastguard. But Ma has also ruled out forming a common front with Beijing. This is an attempt to balance between conflicting pressures from anti-Japan nationalists within his own party and armed forces on one side, and US imperialism on the other side, which is alarmed by the potential schism between Tokyo and Taipei, both key allies in its strategy to contain China.

A new cold war?

The conflict between China and Japan has the potential to destabilise the entire region. Jerome A. Cohen, a veteran China commentator and expert on maritime law, expressed the fear that this was “the region’s most dangerous challenge to peace in over half a century.” [South China Morning Post, 5 October 2012]

During his September visit to Tokyo and Beijing, US Defence Secretary Leon Panetta also cautioned that, “a misjudgement on one side or the other could result in violence, and could result in conflict… And that conflict would then have the potential of expanding.”

Panetta’s statement is steeped in hypocrisy given that the US military ‘pivot’ is a major cause of the current conflict. Right-wing demagogues like Tokyo’s Ishihara know their anti-China brinkmanship is only possible because the US military machine has their back. But Panetta’s remarks show that Washington wants to cool the conflict, fearful of the economic fallout and other uncertainties. US imperialism does not want to be drawn into a military conflict over tiny islands – hence its reiteration of “neutrality” on the Diaoyu/Senkaku issue – although it is also bound by long-standing military treaties to support Japan. In the event that China captured control of the islands by military means, the US would be forced to assist Japan to maintain its own superpower status in Asia.

While a military clash between China and Japan is therefore not the most likely perspective in the short-term, even a prolonged ‘cold war’ of economic protectionism and diplomatic sanctions would deal a major additional blow to the global economy. This point was made by the IMF chief Lagarde, expressing the fears of the capitalist class globally when she said at the IMF-World Bank summit in Tokyo that the world “cannot afford” a conflict between China and Japan.

Negotiations between Beijing and Tokyo are taking place behind the scenes, with both sides anxious to defuse the current standoff fearing the economic costs can soon translate into anti-government sentiment. But it remains to be seen whether a face-saving compromise can be achieved. At the very minimum this would entail an admission by the Japanese side that the status of the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands is disputed. While a military clash is unlikely, it is possible the current deadlock could drag on, with the risk of new diplomatic flare-ups, more nationalist protests, and tit-for-tat economic sanctions.

Nationalist politicians

Even aside from the economic damage caused, the fanning of nationalism and racism by ruling elites throughout the region means they are playing with fire. Right-wing nationalist ideas and movements are gaining ground, especially without a counterweight – in the shape of genuine left parties – showing the need for common struggle by the masses across national borders against the corrupt elites that are plundering the region’s wealth.

There is a clear link between the latest upsurge in nationalism and the imminent change of governments in China, Japan and South Korea. In all cases these are fundamentally weak and unpopular governments, wracked by internal splits. Either the governments themselves (as in South Korea) or capitalist opposition forces (as in Japan) have seized on these long-standing territorial disputes to whip up nationalism, divert attention from unpopular economic policies, and advance pro-capitalist political agendas.

In Japan the ‘brains’ behind the latest chapter of the Diaoyu/Senkaku conflict is Tokyo’s governor Ishihara, a right-wing nationalist and “old-fashioned xenophobe” who the New York Times described as “Japan’s Le Pen”. Like the far right leaders of two other major cities (Hashimoto in Osaka, and Kawamura in Nagoya), Ishihara is a historical revisionist who denies Japanese atrocities during the Second World War, including the forced military prostitution of 100,000s of Korean and Chinese ‘comfort women’. Kawamura, whose city is twinned with the Chinese city of Nanjing, made the incredible statement that the Nanjing Massacre of 1937 “never happened”. Ishihara sprang to Kawamura’s defence.

These hardline nationalists are exploiting the crisis in the East China Sea to position themselves as a ‘new’ force on the national political stage. Toru Hashimoto, the governor of Osaka, has launched the ominously named Japan Restoration Party, which includes a map of the Diaoyu/Senkaku and Dokdo/Takeshima islands on its party logo. The newly-elected Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) leader Shinzo Abe, another virulent nationalist, is likely to seek alliances with the extreme right if, as expected, he wins the coming election. These forces represent the most vicious wing of the Japanese bourgeoisie, who want to dispense with the fetters of ‘pacifism’ both in international affairs, but also in confronting the Japanese working class. Despite a commanding lead over the lame duck Noda and his Democratic Party (DPJ), even the LDP can only muster 35 percent in opinion polls. Half the population supports no party – underlining the yawning political vacuum and possibilities for a genuine left alternative in Japan.

Ishihara instigated the current conflict with China in order to advance a right-wing political agenda that goes far beyond the Diaoyu/Senkaku issue. He used his campaign to buy the islands on behalf of the Tokyo municipality both to subvert Noda’s crisis-ridden government, but also to push forward his agenda for a militarised and nuclear–armed Japan. Unfortunately, the equally nationalistic and militaristic message from China’s regime-controlled media has only assisted Ishihara & Co.

A case in point is the call made by Chinese generals and academics for the current dispute to be “widened” beyond the Diaoyu Islands to include the entire Ryukyu archipelago, including Okinawa with its 1.3 million inhabitants (and big US military bases). These calls are based on the dubious assertion that before its incorporation by Japan, the Ryukyu Kingdom was a Chinese tribute state under the Ming and Qing dynasties. Even on some anti-Japan protests in China, placards have been seen with slogans such as “Retake Ryukyu” and “Take back Okinawa”. While Okinawans are a culturally and linguistically distinct group that suffer discrimination in Japan, there is little support for independence on the island, and no support whatsoever for a Chinese takeover. Regardless of Beijing’s official position, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has encouraged these outbursts in its war of nerves with Tokyo. Rather than anti-imperialism, such slogans convey an expansionist and imperialist agenda.

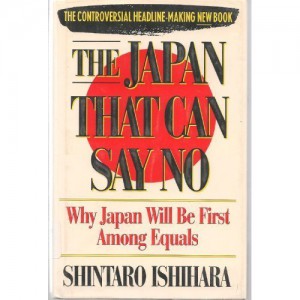

Ironically, Ishihara previously made demagogic attacks on the US (co-authoring the anti-US best-seller ‘The Japan That Can Say No!’ in the 1980s), but is now happy to shelter under US military protection in order to bait China. Like other nationalist politicians, including most top leaders of the LDP, Ishihara says Japan must become a ‘normal’ country – in other words a ‘normal’ imperialist power – with a strong military that is focused not just on ‘self-defence’ but on projecting power overseas.

Rise of Chinese imperialism

With its companies establishing an ever larger presence across Asia and globally, the emergence of Chinese imperialism is increasingly a fact, and is reflected in the regime’s policy agenda just as it is in Japan. Likewise, the nationalist propaganda of the Chinese state, while manipulating widespread and genuine indignation over the horrors of Japan’s occupation, is used more and more to stress its superpower status.

According to The Nation (Bangkok): “China no longer sees itself as a developing country, but rather as a major power to be reckoned with on the global stage. With this unprecedented confidence has come more bullish foreign policy.” [6 October 2012]

Chinese capital now plays a major role across Asia and globally, with China’s annual outward direct investment increasing nearly 20-fold from US$3 billion in 2003 to US$58 billion in 2010. This lifted China to fifth-place in the world for outward foreign direct investment. Under Beijing’s ‘Go global’ strategy, government-linked companies such as Lenovo, Huawei, BaoSteel and PetroChina have engaged “aggressively” in foreign acquisitions. In Africa and Latin America, China’s state-owned China Development Bank and China Export-Import Bank have lent more money to governments in the past two years than the World Bank (in which China is also the third largest shareholder). Most Chinese loans are tied to infrastructure projects and backed by deals involving energy and other raw materials.

Lenin identified the export of capital as a key feature of imperialism. Imperialist relations are today expressed indirectly in most cases through economic domination and ‘neo-colonialism’ rather than formal colonisation. But military power and the ability to project this power across land and sea borders is ultimately tied up with the need of capitalists and big corporations to defend investments, markets, and sources of raw materials.

Korea-Japan tensions

Events in South Korea show the political upheavals that loom on the basis of US and Japanese militarisation plans. In July, the pro-US government of president Lee Myung-bak was forced into a humiliating retreat over its planned military agreement with Japan. The General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA) would have been the first military pact between the two countries since the end of the Japanese occupation of Korea in 1945. Lee was forced to abort this plan, less than an hour before the official signing ceremony, amid opposition from all parties in the national legislature including his own right-wing Saenuri (New Frontier) party.

It is this climb-down that explains Lee’s subsequent visit, the first by a South Korean leader, to the Dokdo Islands, which are held by Seoul but also claimed as the Takeshima Islands by Japan. This was an attempt by Lee and the ruling party to harness the upsurge in anti-Japan sentiment in the run up to December’s presidential poll. The issue spilled onto the football pitch when Japan lost to South Korea in the London Olympics bronze-medal match. Korean player Park Jong-woo was penalised with the loss of his medal for celebrating with a sign that read, “Dokdo is our territory”.

The collapse of the Seoul-Tokyo military pact was a setback for US imperialism, which brokered this deal as part of its ‘tri-partite alliance’ with South Korea and Japan to step up the pressure on North Korea, and implicitly also on China. “Even as it wants a revamped presence in Asia, it [the US] despairs that its chief regional allies cannot get on,” commented The Economist (18 August 2012). The tensions are such that during a joint military exercise in September, a Japanese warship was refused permission to dock in South Korea’s Busan port. Tokyo slammed the decision as “extremely rude”. This underlines the complexity of the power games unfolding in Asia, which will not proceed according to any grand design, whether from Washington or elsewhere. The South Korean capitalists are also eager to flex their muscles as a growing regional power. The tensions between Taipei and Tokyo over the Diaoyu/Senkaku issue similarly underscore the problems for US imperialism as it attempts to reconcile Asia to Japan’s rearmament.

The nationalist grandstanding of Lee Myung-bak’s government is full of ironies. The South Korean elite carries the historical baggage of collaboration during the brutal Japanese colonisation from 1910-45. The core of the South Korean state formed under US protection at the start of the Korean War rested heavily on Korean officers who had served in Japan’s colonial army. This includes the late dictator Park Chung-hee, whose daughter Park Geun-hye is the Saenuri Party presidential candidate. Her defence of her father’s repressive record serves to underline the anti-democratic inclinations of South Korea’s ruling class, a trait it shares with capitalist rulers across the region.

Closely intertwined

With demonstrations in over 120 Chinese cities, some degenerating into riots, the latest flare-up in the East China Sea has inflicted significant losses upon Japanese-invested companies. China is crucial to Japanese capitalism: its number one export market and a major production base for Japanese multinationals. But the Japanese economy is also crucial to China as its second largest export market, and second largest provider of foreign direct investment. Japanese companies invested US$5.1 billion in China in the first eight months of 2012, second only to Hong Kong. Around 700,000 Chinese nationals currently live in Japan. Trade between the two economies has tripled to US$345 billion in the past decade, dwarfing any prospective gains from oil or other resources around the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands.

The island conflict has above all been a setback for Japan’s automakers in the world’s largest vehicle market. For Nissan this is especially the case, as China accounts for 27 percent of its global sales. Nissan reported a US$250 million loss during just one week in September arising from the anti-Japan demonstrations in which several car showrooms were attacked, production facilities closed, and Japan-branded cars came under attack.

Toyota sales fell 49 percent in September from a year earlier, while Honda sales fell 40.5 percent. As the Financial Times reported, the Japanese share of China’s vehicle market has slipped from 26.6 percent in 2009 to 22.8 percent, allowing German carmakers to overtake their Japanese rivals for the first time. Korean carmakers are also ecstatic, as their slice of the China market has grown at the expense of Japanese brands.

Rather than a purely spontaneous movement, the boycott of Japanese goods is being used by the Chinese regime as a deliberate weapon to increase pressure on Tokyo. But this is a tactic fraught with risks, in a global economic environment where protectionist pressures are rising and Chinese companies are themselves increasingly encountering barriers.

The China-Japan crisis and other regional conflicts could therefore become a further serious drag on the region’s economy, already reeling from the effects of the debt and financial crises in Europe and the US. Economists at JPMorgan Chase warn the Diaoyu/Senkaku Island territorial clash will shave 0.8 percentage points off Japan’s GDP growth for the fourth quarter, sending the overall economy into recession. The Chinese economy, which is already on course for its weakest annual growth for 13 years, could also pay a heavy economic price.

The boycott calls against Japanese companies threaten to boomerang on the Chinese economy. “This is probably the most tightly integrated region in the world in terms of trade and investment,” warned the former US ambassador to South Korea, Stephen Bosworth. This was shown by last year’s tsunami and nuclear catastrophe in Japan, which disrupted supply chains and factory output throughout the region.

According to John Gong, associate professor at the Beijing-based University of International Business and Economics, “The two nations are today so closely intertwined economically that it’s even hard to actually define a Japanese product. Parts and components made in Japan probably permeate every sophisticated electronic product. Apple iPhones, Lenovo laptops, Haier television sets, to name just a few, all have things in them that were made in Japan.”

Many Japanese branded goods are actually manufactured by joint-ventures in China – using Chinese capital and Chinese workers. This is the case in the auto industry where most of the production of Toyota, Nissan and Honda cars is from joint-ventures with state-owned enterprises. As Gong argues, “Boycotting cars from them is essentially the same as boycotting those Chinese companies.”

Anti-Japan demonstrations

Given the legacy of Japan’s wartime atrocities there has been understandable anger and fear among the Chinese masses over what is seen as a provocative and unilateral act by the Japanese government, egged on by extreme nationalists supported by US imperialism. The protests also reflect much wider issues of growing discontent and frustration in society. But the Chinese regime has manipulated this sentiment, translating it into the language of chauvinism and militarism, in order to promote its own superpower aims and shore up domestic support.

The Standard (Hong Kong) speculated the protests in mid-September were the largest in China since the 1989 pro-democracy movement. Japan’s Kyodo News said protests occurred in as many as 125 cities. The Chinese regime used these protests to increase the pressure on Japan and the US. Although it sanctioned the demonstrations, including cases of companies giving workers time off to participate, and security forces ‘directing’ crowds, the movement was not fully under the regime’s control. In many cities the protests took on a decidedly anti-government character, but in a muddled, contradictory way, which combined extreme nationalism with hostility to the CCP and its pro-capitalist policies. For this reason the demonstrations were only tolerated for a short period by the regime.

Liberal Chinese blogger ‘Anti’ told Japan’s Asahi Shimbun (16 October 2012): “Because protests are in general prohibited, when a window of opportunity was opened, people from a range of backgrounds took part… The demonstrations were complicated. They represented anti-Japanese sentiment mixed with a certain form of class confrontation… The rapid rise in references to Mao, including by groups that support Bo Xilai (a senior official recently expelled from the Communist Party), has surprised many Chinese people, including me…”

The appearance of Mao’s image on demonstrations across the country was a shock and embarrassment for the regime, and especially its liberal wing. Many complained that the protests, which included the ransacking of Japanese department stores and other acts of violence, “resembled the Cultural Revolution”. The factional supporters of Bo Xilai within the party and security apparatus undoubtedly used these protests as an opportunity to embarrass Beijing and accuse it of “weakness” against Japan. This may in fact have tipped the balance as far as Bo’s fate is concerned, with the top leadership mustering sufficient ‘unity’ to expel him from the CCP and initiate criminal proceedings shortly after these protests.

Despite being a millionaire, Bo Xilai is seen by many radical youth especially as a thorn in the side of the current pro-capitalist leaders in Beijing. Many neo-Maoists, who have been active in the anti-Japan protests, see Bo as an advocate of a more nationalist and assertive stand towards foreign capitalism. Ironically, in Dalian, regarded as the launching pad for Bo Xilai’s national political career, there were reportedly no anti-Japan protests. One-third of foreign companies in Dalian are Japanese-owned and the city of 6 million is a centre of Japanese language education with more than 200,000 students. It is Bo, who was mayor of Dalian during the 1990s, who is credited with attracting Japanese investments.

The use of Mao placards on the protests also reflects complex political processes. Undoubtedly Mao’s image is a popular way to express opposition to the current CCP leadership. But the resurgence of Maoism does not necessarily imply a grasp of left-wing or socialist ideas. Many linked their support for Mao with calls for war against Japan.

The problems for the regime came not only from Mao and supporters of Bo Xilai. Some protesters in Guangzhou and Shenzhen held banners calling for “political reforms” and greater democracy. In Shenzhen, where the demonstrations were reportedly the most violent, there are clearly wider issues especially among the city’s majority migrant workforce as the economic crisis deepens. Police in Shenzhen clashed with protesters who tried to storm a government office. Some have speculated the violence was orchestrated by factional supporters of Bo and ex-president Jiang Zemin in order to embarrass Guangdong party boss and leading liberal Wang Yang, to sabotage his chances of elevation to the Politburo Standing Committee.

Clearly the bitter internal power struggle within the Chinese regime spilled into the anti-Japan protests and influenced their chaotic and contradictory character, underlining the current fragility of the regime and the limits of control from the centre. This experience will reinforce the cautious elements within the current leadership and the desire to pursue their grievances with Japan through official channels. There is no guarantee however that this will deliver results, and therefore new upheavals, possibly triggered by internal factional strife, cannot be excluded.

In evaluating any mass movement socialists must take all sides into account, separating the progressive features from the reactionary. These protests expressed the extremely confused consciousness of the Chinese masses today. While attracting support from many layers who oppose CCP rule, the protests channelled this in the direction of nationalism and militarism. Moreover the protests have had a negative effect upon the consciousness of the masses in other parts of Asia, where the so-called ‘China threat’ is being exploited by local ruling classes and the US for their own ends. In Japan, rather than undermine the nationalist right these developments have helped them. The reactionaries on all sides – who may be prepared to gamble on military action in the future – can only be defeated through working class struggle and the creation of a socialist alternative in Japan, China, and across the region.

In all the countries of the region there is a massive political vacuum on the left, brought about by the degeneration and collapse of former mass left parties. It is noticeable that ex-Stalinist parties everywhere serve as loyal adjutants of their capitalist governments in today’s territorial disputes. The Japanese Communist Party, while distancing itself from Ishihara’s provocations, supported Japan’s nationalisation of the Diaoyu/Senkaku to “calmly maintain” (!) the islands. In the Philippines the exiled former Maoist leader Jose Maria Sison defends Manila’s “national sovereignty” in the Scarborough Shoal dispute with China.

What socialists stand for

Socialists and the supporters of the CWI do not support any of the feuding governments or states in these territorial disputes. We oppose Japan’s control of the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands and the Noda government’s nationalisation, which has further inflamed the situation.

We defend the rights of fishermen from all the neighbouring states to access these disputed waters, while also recognising the urgent need for a comprehensive international plan to safeguard endangered marine life and prevent overfishing. We oppose the harassment and detention of fishing crews by national coastguards, of which all governments have been guilty, and the use of fishing fleets as a disguised tool of government policy in these disputes.

Socialists oppose the provocations of the Japanese capitalists and extreme right, but not by supporting the slogan of Chinese sovereignty over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands. The Chinese regime is also using this issue, and the legitimate fear of Japanese militarism among the Chinese people, to further its own great power ambitions. The regime’s nationalistic rhetoric and racist, warmongering statements broadcast in sections of the official media, rather than weakening the Japanese nationalists, have played into their hands.

The Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands are uninhabited and therefore this is not a struggle to defend the rights of an oppressed people. As in the South China Sea, this conflict is primarily about strategic control of the seas, the resources below, and the military implications associated with control over the islands.

Socialists and the CWI warn that the current nationalist wave instigated and manipulated by leaders on all sides, will be used to bolster repressive, anti-democratic and anti-working class policies. The right-wing nationalists in Japan are anti-union, anti-foreigner, and oppose women’s and LGBT rights. They represent a growing threat to the interests of Japanese workers and youth. Hashimoto supports military conscription and – echoing China’s leaders – says Japan needs a “dictatorship”, albeit one subject to electoral checks and balances. Their policies would add massive military costs to the current economic burdens of the Japanese masses.

But the way to defeat Japan’s nationalists and warmongers is through common struggle and solidarity by workers and youth in China, Japan, Korea, and throughout the region, with the recent huge anti-nuclear protests in Japan showing a good example.

Socialists oppose the militarisation drive of all governments in the region, pouring money into armaments and upgraded naval forces at a time when working people everywhere lack affordable housing, secure jobs, good quality and affordable education and healthcare. We demand massive cuts in military spending; for a transfer of resources to meet society’s real needs. Socialists and the CWI demand the closure of US military bases, such as those in Okinawa, which have long been opposed by the local population. We demand the total withdrawal of US forces from Asia – for the people of the region to decide their own future.

There can be no solution to today’s national conflicts on the basis of capitalism. Some voices are calling for a new (capitalist) regional forum to oversee ‘risk management’ and prevent conflicts. Others are pointing to the European Union (EU) as a possible model of multi-national cooperation. But not even the Nobel prize can hide the acrimonious disunity and splits within the capitalist EU, which was always contrived as a means for the ruling classes to maximise profits at the expense of the masses. Likewise, the 10-nation ASEAN (Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia. Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam) has been powerless to offer a solution to the territorial disputes among its own members concerning islands in the South China Sea.

Rather than control by one or other national gang of thieves, the resources of the ocean and its endangered fishing stocks should be jointly owned, controlled and democratically managed by the peoples of the region. The rush to plant flags on uninhabited islands and rocks, and the nationalist-militarist chorus this engenders, go against the interests of the working class everywhere. Socialists stand for shared access to these islands and the surrounding waters, superseding national control through the establishment of a ‘maritime commons’ under the democratic control of the people of China, Japan and all the neighbouring countries. We stand for an Asian socialist confederation, established through mass working class struggle, to replace the misery and chaos of capitalist rule.

| The ‘Return the Diaoyu’ campaign in Hong KongIn August a boat full of campaigners sailed from Hong Kong and managed to stage a landing on one of the Diaoyu Islands. This protest was organised by the Action Committee for Defending the Diaoyu Islands. This group receives funding from many different political groups, and includes former left activists whose position on the Diaoyu Islands is coloured by 1970s geopolitics, with China under Mao representing an alternative to capitalism and imperialism, albeit as a very bureaucratic and distorted planned economy, which claimed to be ‘socialism’. This is no longer the case, as China has increasingly embraced capitalism.

But the Action Committee also gets substantial funding from veteran figures within the pro-CCP establishment, including Lew Mon-hung who is a delegate to the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) and a prime mover behind Leung Chun-ying’s bid to become Chief Executive. Lew has donated HK$4 million to the group in the last six years. As the well-known saying goes, “He who pays the piper calls the tune.” Why would these enemies of democratic rights finance the campaign if, as some Diaoyu campaigners have claimed, their protest represents some sort of challenge to the CCP? This Diaoyu boat expedition clearly enjoyed the tacit backing of Leung Chun-ying’s administration. According to the South China Morning Post (17 August 2012), Leung himself made a financial donation to the expedition in the form of a painting for auction, as did DAB (Hong Kong’s main pro-CCP party) heavyweight Tsang Yok-sing. Hong Kong’s marine police, who have intercepted every attempt since 2004, did not prevent the boat from leaving Hong Kong waters. On board, in addition to four flags (!) – those of China, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Macau – was a film crew from pro-Beijing Pheonix television. Leung’s administration saw that it could benefit if this issue was blown up large just weeks before an election in which it was under fire, particularly to use as a counterweight to the massive protests against his national education or school ‘brainwashing’ policy. |