Has China’s economy turned a corner?

Analysis by chinaworker.info

Has China’s economy turned a corner? Premier Li Keqiang and the Chinese government certainly want us to believe that. The reality however is continuing weak growth despite a series of major stimulus measures that revive memories of Beijing’s mega-stimulus package in the wake of the 2008 global capitalist crisis. The build-up of debt, which is the inevitable result of these policies, is increasing the risk of a financial collapse or as a ‘best case’ scenario Japanese-style economic stagnation. This is something that even senior Chinese officials are now openly warning about.

In an unprecedented sign of splits at the top, the People’s Daily published a front-page editorial (9 May 2016), in which an unnamed ‘authoritative source’ savaged the government’s policies. Rather than an economy in recovery mode, the source said, the trajectory was L-shaped. “I need to stress, that the L-shape will last for a certain period of time, and it’s certainly longer than one or two years,” he warned.

The mystery source is clearly a regime heavyweight or his comments would not have been featured so prominently in the CCP’s (so-called Communist Party) main mouthpiece. It is widely believed to be Liu He, Xi Jinping’s top economic guru who heads the general office of the Central Leading Group for Financial and Economic Reform. Stimulating growth by increasing debt was like “growing a tree in the air”, he said, warning that this could “trigger a systemic financial crisis”.

The People’s Daily editorial punctured a bubble of positive economic spin from the government, an attempt to shake off its crisis image. Beijing-based economist Anne Stevenson-Yang says the economy has experienced a “dead panda bounce” rather than a real recovery. “Behind what looks like recovery in the Chinese economy are massive new injections of liquidity and unrelenting jawboning from the top about the strength of the economy,” she commented.

Fed u-turn

China’s stock markets and currency nosedived at the start of the year, the second big wave of financial turmoil since the spectacular stock market implosion of last summer. But by late February both China’s and global financial markets had steadied. This was above all due to the US Federal Reserve Bank’s change of stance; putting further interest rate rises on hold, after its mistimed increase in benchmark lending rates last December.

That was the first rise in US rates in nine years. By appearing to signal the end of the Fed’s historically unprecedented cheap credit policies (quantitative easing) it triggered a flood of speculative capital back into the US as the dollar climbed against other currencies. Capital was sucked out of the so-called emerging markets of which the biggest by far is China, popping bubbles in property markets, stocks and other financial assets. This new flare-up of the ‘emerging markets crisis’ threatened to kill off the faltering global recovery.

By deferring further rate hikes the Fed temporarily steadied the ship and gave China’s embattled financial authorities a breathing space. As the dollar reversed course and began to weaken against other currencies this relieved pressure on China’s central bank, which until this point was spending heavily to shore up the yuan in an effort to staunch massive capital flight. Bloomberg estimates that China suffered a net outflow of US$1 trillion last year – almost 10 percent of GDP. This represents a historic reversal after years of net inflows. At the time of writing, however, the dollar is again rising – sharply in the wake of ‘Brexit’ – increasing the pressure once more on China’s central bank.

The cost to the Chinese state has been astronomical with its foreign exchange reserves cut to US$3.19 trillion this May from a peak of US$4 trillion two years earlier. To stem this ‘cash drain’ Beijing moved to tighten its leaky capital controls. But this is seen only as a temporary expedient because a return to strict capital controls would thwart the global ambitions of China’s biggest companies, which are engaged in furious outward expansion.

Heading for a debt crisis

The stampede of capital out of China has the potential to trigger a banking crisis or – more immediately – to force Beijing into a drastic devaluation of the yuan. This would almost certainly spark a wave of copycat devaluations (a so-called ‘currency war’) especially in Asia and other emerging markets. Many commentators have therefore drawn parallels with the 1997 Asian Crisis, also triggered by massive capital flight which upended the region’s currencies and triggered severe recessions from Seoul to Jakarta.

It is true that a state-owned banking system gives China greater defences against such a scenario, but only up to a point. The state-owned sector in China is actually a collection of competing geographic and economic entities which pull in different directions. What is significant about the Chinese regime’s crisis response so far is that is consists only of adding more debt in the hope of muddling through. This is a policy that on one hand becomes progressively less effective (more and more debt is needed to create ever weaker bursts of growth) and on the other hand stores up bigger problems for the future.

Beijing’s officially stated aim, reiterated at the March NPC meeting, is to achieve average annual growth of 6.5 percent from now until the year 2021. “This probably requires that by 2021 total debt will rise to a level equal to between 360 percent and 540 percent of China’s GDP,” says Beijing-based economist Michael Pettis. “This, to put it mildly, is implausible.” [FT Alphaville, 2 June 2016]

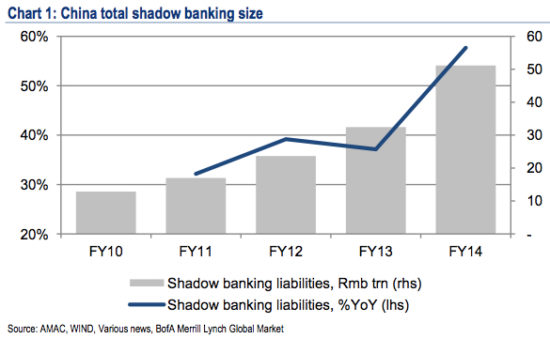

George Soros, the billionaire speculator, warned recently that China’s dependence on debt bears an “eerie resemblance” to the conditions leading up to the 2008 financial crisis. The explosive growth of shadow banking in particular betrays many similarities with the US. This is an area of the economy where – by definition – state control doesn’t exist.

Economist Charlene Chu, an expert on China’s banks, believes an “aggressive bailout” of the banking system will soon be needed. She estimates the real extent of bad loans – officially just 1.75 percent – is around 22 percent of total banking assets. This is not far from the estimates of Hong Kong-based brokerage CLSA, published in a May report, which puts non-performing loans (NPLs) at the “crisis level” of 19 percent. With total assets (i.e. loans) worth US$28 trillion, this means a staggering US$5 to 6 trillion in NPLs.

As China’s economy has slowed to it’s weakest growth in 25 years, probably substantially below the 6.9 percent Beijing claimed last year, the debt mountain has continued to grow. A report by Goldman Sachs (2 July 2016) says China’s debt-to-GDP level rose from 154 to 249 percent between 2008 and 2015 – a result that “ranks in the 98th percentile of debt buildups in modern history.” According to this report only countries that have been at war have experienced anything close.

“My own guess is that Beijing has two to three years – perhaps four if global conditions turn very positive – but not more than that before debt levels become so high that growth grinds to a halt,” says Pettis.

Shadow banking: an $8 trillion industry

The bad numbers don’t stop there. In the first year of his Premiership, Li Keqiang’s policies seemed to have a certain effect in slowing the growth of shadow banking, which involves far greater financial risks because it is outside government regulation and spreads its financial tentacles in ways that even insiders don’t understand.

But China’s shadow banking sector has resumed its explosive growth. This is partly in response to Beijing’s cuts in interest rates, but is also due to capital migrating from the lacklustre stock market. Shadow finance is especially popular with regional and local governments, and the state-owned banks which in reality are dictating the growth of shadow banking, using this as a “hidden second balance sheet”, to quote the economist Chu, to conceal the full extent of their assets and liabilities. If the current unsustainable growth of credit in China represents a form of financial ‘steroids’ then the shadow banking sector and its Ponzi scheme ‘investment products’ represents the most dangerous form of ‘steroids’ that can cause death. In China’s case, there is the additional danger that the shadow banking system can serve as a bolthole for capital flight in a future crisis.

According to Moody’s, China’s shadow banking sector grew 30 percent in 2015, to US$8 trillion (around 80 percent of GDP). Furthermore, the fastest growth sector has been for Wealth Management Products (WMPs) which are sold as ‘investments’ but are mostly just bundles of ‘junk’ debt repackaged and sold with promises of a higher-than-average payout. Incredibly, HSBC reported (30 June 2016) that the WMP market is now 24 percent larger than China’s domestic stock market (the world’s second largest). Fundamentally, China’s WMPs are no different from the Collateralised Debt Obligations (CDOs) that proliferated in the run up to the US financial meltdown of 2008.

China’s version of CDOs

Increasingly it is banks – seeking higher profits – that buy them (accounting for one-third of WMP purchases last year). An increasing share of WMPs are also being bought up by other WMPs, meaning the same underlying ‘assets’ are being re-packaged and sold multiple times – replicating exactly the practises that blew up the US banking system. To quote one of the bankers in the movie The Big Short, this is the financial equivalent of “dog shit wrapped in cat shit”.

Charlene Chu calls WMPs “a ticking time bomb”. She points out that if WMPs grow just 25-30 percent this year (last year they grew 57 percent), “they will be twice as big as the combined amount of structured investment vehicles and conduits that blew up on Western banks during the global financial crisis.” [Barron’s 15 April 2016].

At the same time, much of the corporate debt accumulated from the giant stimulus package of 2008 is turning bad. As we have seen, very few economists believe the official figures for non-performing loans (NPLs), i.e. loans that are in default or close to default, currently given as 1.75 percent of total loans. Several recent reports indicate the real level is 10 to 20 times higher.

Reporting from Xi Jinping’s former power base, Zhejiang province, where the official NPL ratio stands at 2.39 percent, the Financial Times (30 May 2016) found that “local bankers estimated that the province’s real NPL ratio is likely in the region of 20-30 per cent.”

Credit surge in Q1

Beijing’s attempts to deleverage (reduce debt levels) have failed or been overridden by contradictory policies and the evasive practises of banks and local governments. Above all this flows from the fear that a sharp drop in growth could unleash an uncontrollable financial and political chain reaction (a banking crisis and mass unrest).

This explains why the creation of new loans surged in the first quarter of this year, hitting a new record. Total social financing (TSF), a broad measure of new credit, soared 41 percent from the same quarter a year earlier to 6.59 trillion yuan (US$1 trillion).

The credit expansion of the first quarter exceeded even the first quarter of 2009, the start of China’s giant stimulus package. This seems to have been a panic response by the government to the sharp deterioration in the economy at the start of the year. This also explains the sharp and unusually public top-level split over economic policy.

The result of this latest credit splurge has been to blow up new bubbles especially in the property market (limited to first and second-tier cities), and even a delusional commodities boom. These bubbles will inevitably burst much like last year’s stocks bubble.

These developments also underline the fact that the central government and its financial agencies are not in full control of economic policy. China’s economy is in practise heavily decentralised with local governments and the companies and banks under their control pursuing their own agendas regardless of Beijing’s wishes. This is a big factor behind the explosion of debt and the ineffectiveness of government attempts to deleverage.

Banks: ‘extend and pretend’

State-owned banks operate a policy of ‘extend and pretend’ – covering up the mountain of bad loans and granting new loans to major clients and local government-backed companies to keep them afloat. Meanwhile the economic slowdown continues. Recent data shows manufacturing industry is still contracting, with employment falling every month for the past two years, and the growth of private sector investment (which drives 65 percent of the economy) has fallen sharply to 3.9 percent in the first five months of this year, compared to 10 percent growth in 2015.

“There’s no chance that China has bottomed out. The idea that China has bottomed out should be stricken from the lexicon, because China is on a long-term slowdown. The question is whether they can engineer this the way they want or whether the circumstances are dictated to them,” says Leland Miller who produces the China Beige Book, a survey of private sector companies in China.

Most of the global banks are trimming their predictions for China’s GDP growth this year – within a range of 6.2 to 6.6 percent. Whatever the official GDP statistics say about the second quarter, it’s clear the downward pressure continues despite the unprecedented credit expansion at the start of the year. Of course, the regime can make up whatever statistics they want and as a fearsome dictatorship no one will openly accuse them of falsification.

The author Fraser Howie, who co-wrote the best seller ‘Red Capitalism’, recounted what the boss of a large European insurer told him after attending a meeting with officials from the People’s Bank of China (central bank) earlier this year. He said the Chinese officials were joking and laughing in derision about official reports showing 6 percent growth.

Unfortunately for China’s working class, facing mass layoffs, wage cuts and economic uncertainty, this is no laughing matter.