100th anniversary of May Fourth Movement – The Chinese dictatorship has many reasons to fear that once again China could be on the threshold of mass protests by radicalised youth and students, which could ignite a bigger movement among the working class

Wang Linyu, chinaworker,info

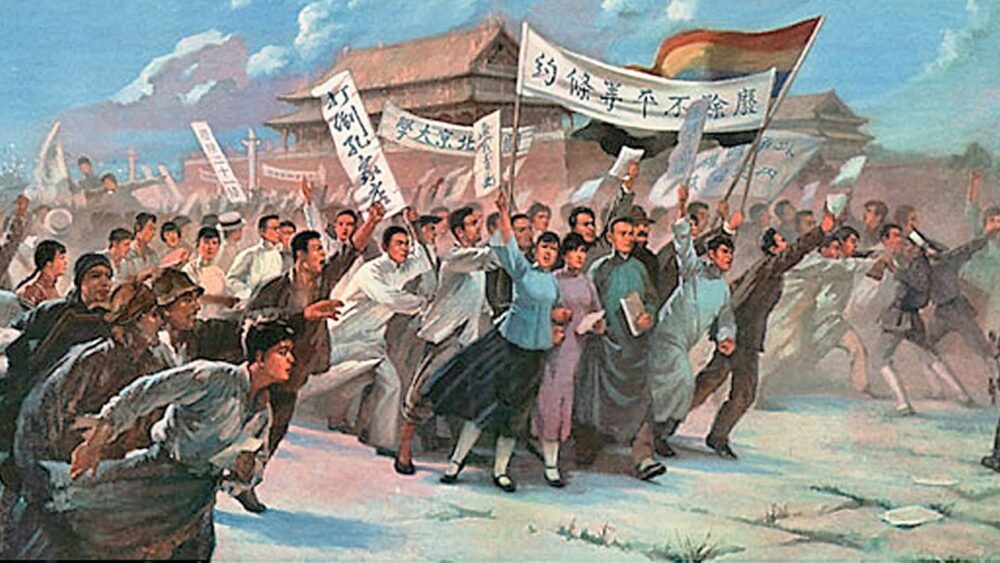

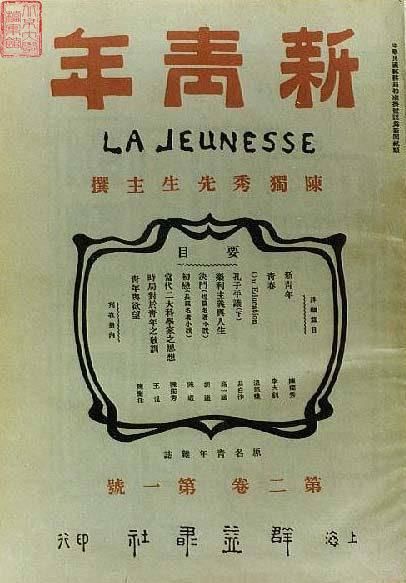

On May 4, 1919, 3,000 college students in Beijing took to the streets protesting against the decision of the Paris Peace Conference, set up after the First World War, to transfer to Japan all the land, railways, mines, forests, etc. previously occupied by Germany in China’s eastern Shandong province. China was politically fragmented, mired in warlord rule, with foreign powers intriguing with rival Chinese rulers for influence and control.

Japan had been on the winning side in the war, allied with Britain and the US, while Germany and the ‘Central Powers’ had been defeated. The May Fourth demonstration unleashed a nationwide mass movement in China that lasted for two months. It also opened a new era of China’s mass struggles especially workers’ struggles. This movement was launched by the students, but then a large number of urban residents, workers, and merchants joined the movement.

Today, the Chinese regime will likely play down the May Fourth Movement anniversary. It has many reasons to fear that once again China could be on the threshold of mass protests by radicalised youth and students, which could ignite a bigger movement among the working class, society’s not-yet-risen superpower, capable of affecting fundamental political and economic change. In a nascent form this potential is shown in the Jasic Technology workers’ struggle of the past nine months.

70th anniversary

It should not be forgotten that the anniversary of the May Fourth Movement was also an important spark for the mass democracy struggle in the spring of 1989, which almost brought down the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) regime. Originally, Beijing university students were planning synchronised protests for the 70th anniversary of May 4, but they brought forward these plans when former CCP General Secretary Hu Yaobang – seen as an opponent of hardline rule – died suddenly on April 15.

In 2019, with multiple sensitive political anniversaries in the calendar, the CCP regime fears “unimaginable dangers” and the historic movement of 1919 is nothing to calm their nerves.

The May Fourth Movement took place amid the global revolutionary wave of the late 1910s, following the mass slaughter of the 1914-18 war. In 1917, the October Revolution in Russia gave birth to the first workers’ state in history and inspired workers’ revolutionary movements and national liberation movements around the world.

On March 1, 1919, two months before the May Fourth Movement began, a massive independence movement broke out in Korea which was a colony of Japan at that time. Two million Koreans participated in thousands of anti-Japanese demonstrations and armed uprisings. On March 2 of the same year, the Comintern (Communist International) was established in Moscow. The May Fourth Movement drew inspiration from these international mass movements.

Luo Jialun, one of the student leaders of the May Fourth Movement, commented on the Russian Revolution in January 1919: “This revolution is one in which democracy defeats monarchism, civilians defeat warlords, labourers defeat capitalists!” He said revolutions would in future follow in the footsteps of the Russian Revolution to completely transform society.

Disillusionment

Shortly after the First World War ended many Chinese intellectuals had great illusions in the imperialist powers. In November 1918, 60,000 people in Beijing participated in a parade to celebrate the allied victory. They believed China would be able to take back the ‘Kiaochow concession territory’ in Shandong, which Germany had occupied since 1898, and could amend the unequal treaties forced upon China by the imperialist powers, thus lifting China out of backwardness and imperialist oppression.

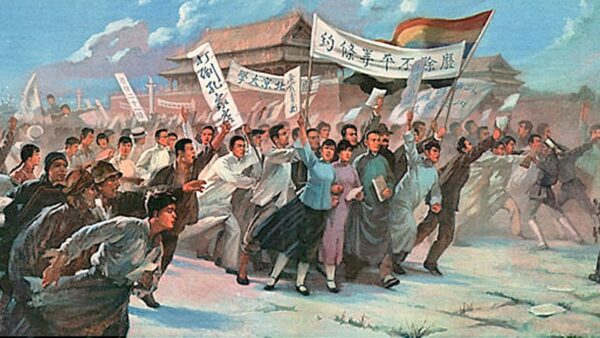

There were especially large illusions in then US President Woodrow Wilson. A late arrival to the game, US imperialism wanted to join the scramble for colonies, trying to undermine the older imperialist powers such as Britain and France by supporting the self-determination of some occupied nations in Asia and Europe. However, in fact, during Wilson’s presidency, the US conducted military interventions in several Latin American countries, forced Nicaragua to sign unequal treaties, and invaded Haiti. Under the ‘Treaty of Versailles’ agreed at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, Wilson also supported the transfer of Germany’s possessions in Shandong to Japan.

At the end of April people in Beijing learned of the decision of the Paris Peace Conference, which caused dismay and anger especially among young intellectuals. A Peking University student at the time recalled: “We were shocked when the news of the Paris Peace Conference finally came here. We were immediately awakened to the reality. The foreign countries are still selfish and militaristic, and they are all liars.”

May Fourth Demonstration

Beijing students had originally planned a demonstration on May 7, but the government had begun to suppress protests and so the demonstration was urgently brought forward to May 4. May 7 was known as ‘National Shame Day’, after the Japanese government in 1915 issued an ultimatum to the China’s autocratic president Yuan Shikai to sign a treaty further tightening Japan’s grip on China. Yuan is an infamous figure who briefly restored the monarchy and was crowned in late 1915, four years after the establishment of the Republic of China, but was soon brought down by other warlords.

On May 4 1919, protesting students set off from Tiananmen Square. Their main slogan was “Fight for sovereignty, get rid of the national traitors”. “Fight for sovereignty” meant refusing to sign the Treaty of Versailles, while “get rid of the national traitors” meant removing pro-Japan officials in the Beijing government.

The three most important traitors were Cao Rulin, Minister of Communications, Zhang Zongxiang, Ambassador to Japan, and Lu Zongyu, the Chinese director of the Chinese-Japanese Exchange Bank. The protesters marched to the embassy district, which they originally planned to enter, but were blocked by the police. According to an unequal treaty signed in 1901, (after the suppression of the Boxer Rebellion) Chinese were banned from marching in the diplomatic quarter.

After a two-hour standoff with the police, angry students turned to Cao Rulin’s home, where they broke through the police cordon and entered his house, smashing belongings and beating up Ambassador Zhang who lived there at that time. Some angry students set fire to the building. Due to the fire and police reinforcements, protesting students gradually dispersed, with 32 students arrested. Some of the protesters went to the banker Lu Zongyu’s home, but the army had already been stationed there so there was no conflict. The demonstration on May 4 thus ended.

‘Twenty-One Demands’

Cao, Zhang and Lu became the primary targets of the students because they had participated in negotiations between Yuan Shikai’s government and Japan on the unequal treaty of 1915, known as the ‘Twenty-One Demands’. They has also participated in a huge Japanese loan programme, under the control of Duan Qirui, who became the dominant figure in the Beijing government after Yuan’s downfall.

Both the 1915 treaty and the loan aimed to extend Japanese imperialism’s control over China and became important background for the outbreak of the May Fourth Movement.

At the beginning of 1915 the Japanese government made the 21 demands to Yuan Shikai, aiming to turn northeastern China (Manchuria), Inner Mongolia, Shandong, the southeast coast and the Yangtze River basin into Japanese colonies. They also attempted to control China’s internal affairs by forcing Yuan’s government to hire Japanese consultants, who would have decision-making power over political, financial and military affairs. Significantly, in the related treaty, Yuan promised to transfer Shandong to Japan.

Anti-Japanese mood

By the end of 1916, Japanese capitalism wanted to export its excess capital, built up during wartime, to China in order to obtain greater control over its economy and politics. Ironically, the capitalist CCP regime today has similar ambitions through its ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ across big parts of Asia and beyond.

From January 1917 to September 1918, Japan provided the Beijing government with a total of 145 million yen in loans. In return the Beijing government mortgaged its state-owned industries and signed a “military cooperation agreement” with Japan which further increased Japanese control. The loans were nominally driven by economic considerations but were actually used by the Beijing government to bribe legislators and wage war against the Guangzhou military government led by rival warlords in southern China.

New Youth magazine

Both the ‘Twenty-One Demands’ and the Japanese loans triggered a lot of protests and a boycott of Japanese goods. After Yuan Shikai’s government accepted the demands in 1915, a large number of Chinese students and youths in Japan returned to China, including Chen Duxiu, an important figure in the May Fourth Movement.

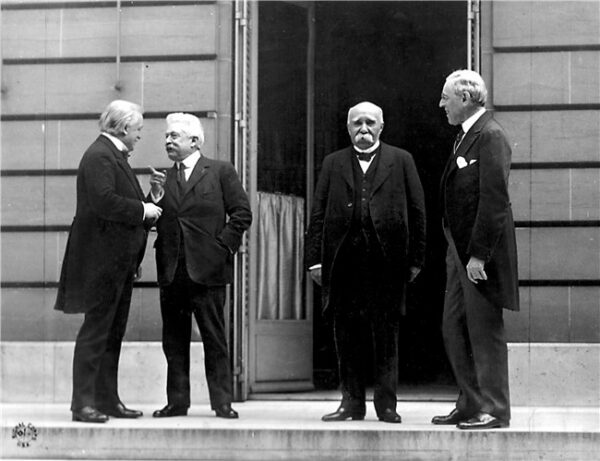

Upon returning to China, Chen founded the New Youth magazine, which became a powerful voice of the New Culture Movement and the May Fourth Movement. The New Culture Movement, launched by young intellectuals who had obtained a western education, was a bourgeois reform movement in the name of “renaissance”, advocating science and democracy against China’s feudal social system and culture.

Many of the students brought into activity around New Youth became founding members of the Communist Party. In May 1918, students in many of China’s main cities issued petitions and held demonstrations against the Japanese loans, and this became a rehearsal for the May Fourth Movement. After this wave of protests in May 1918, there emerged more progressive student groups that later actively participated in the May Fourth Movement.

Student organisations

After the May 4 demonstration in Beijing the mass movement continued to develop. Beijing students continued their protests, street speeches and boycott of Japanese goods, and began sporadic student strikes. On May 6, the ‘Union of Secondary and Above Students’ was established in Beijing. This was the first citywide student organisation in China’s history. In the next two weeks students in other cities also began to hold protests and mass meetings and establish mass student organisations.

At the same time, the warlords and conservative bureaucrats in the Beijing government hoped to use the May 4 demonstration as an excuse to suppress the student movements and the New Cultural Movement, with Peking University as one of their main targets, because it was also the stronghold of the New Culture Movement.

On May 14, the Beijing government decided to use military force to suppress student activities and declared that students had no right to interfere with government policies. Some student publications were banned and the government was preparing to use the army to disband student organisations and force striking students to go back to classes. Warlords in other parts of China also suppressed the student protests.

On May 19, 25,000 college students in Beijing began a general strike. In the ensuing month the wave of student strikes spread to 200 cities and towns. By the end of May, the government slightly softened the crackdown in the face of extensive protests, and student activities eased. This led the government to mistakenly think the time had come to completely suppress the movement.

On June 3, more than 900 students who were making public speeches on the streets were attacked by police and 400 were arrested. This led to more students joining in street speeches. By June 4, more than a thousand students were arrested, but the number of students who took to the street increased to 5,000 on June 5. Many students were ready to be arrested, carrying food and bedding to be used in prison.

Movement’s centre shifts

The news of harsh suppression in Beijing reached Shanghai. In response to the appeal from students, historic workers’ and merchants’ strikes broke out and became the key force for the victory of the May Fourth Movement. Shanghai, the stronghold of Chinese capitalism, became the new centre of the movement.

Shanghai students followed Beijing students to establish a citywide student union on May 11, and they more consciously expanded the scope of the movement. The Shanghai student union had a Department of Labour to liaise with workers. They also sent people to the chambers of commerce to call for support.

On June 16, student leaders across the country gathered in Shanghai to establish the China Student Union, which was responsible for coordinating the student protests throughout the country.

On June 5, almost all Chinese merchants in Shanghai ceased trade, including those in concession territories (controlled by foreign powers) and suburbs. China’s emerging capitalist class had a contradictory attitude towards the May Fourth Movement. During the First World War the western imperialists turned their attention to arms production, so exports to China decreased and the Chinese capitalists gained a brief breathing space. When the war drew to an end, the imperialists turned their attention back to China, especially Japanese imperialism, which forced the Chinese capitalists back into harsh competition with foreign capital and goods.

Therefore, sections of the Chinese capitalist class wanted to use the anti-imperialist mood to capture a bigger share of the home market. Meanwhile, the widespread and strong nationalist sentiment at the time also put tremendous pressure on the national capitalists.

Workers’ strikes

At the same time, more importantly, Shanghai workers began to strike. The strikes began in the textile and printing industries and then spread to metals and other industries. The number of strikers is estimated at 60,000-100,000, involving about 50 companies. This was the first political strike of China’s working class. Workers’ strikes quickly spread to other cities including Hangzhou, Jiujiang, Tianjin, as well as the workforce of two railways. Workers from many other cities also participated in big mobilisations.

On June 10, the Tianjin Chamber of Commerce sent an emergency telegram to the Beijing government saying, “There are hundreds of thousands of workers in Tianjin. Now the unrest is emerging among workers. If the government hesitates to remove Cao Rulin, Zhang Zongxiang and Lu Zongyu, once workers began to strike, the losses will be much larger than the merchants’ strike.”

With the beginning of strikes the imperialist powers changed their attitude towards the May Fourth Movement. Western imperialists were wary of Japan’s expansion in China and hoped to use the protests to check its influence. Therefore, these powers adopted a wait-and-see attitude at the beginning and sometimes even expressed sympathy for the movement.

Pressure on Beijing

However, on June 6, the concession authorities announced a ban on distributing leaflets, public gatherings and banners related to the movement. Student organisations and workers’ strikes were forcefully suppressed within the concessions.

Meanwhile, under the strong pressure of the mass movement the Beijing government announced on June 10 the dismissal of Cao Rulin, Lu Zongyu and Zhang Zongxiang. The Workers’ and businessmen’s strikes across the country gradually ceased, but protests continued calling on the government not to sign the Treaty of Versailles.

On the signing date of June 28, China’s negotiators in Paris did not sign the treaty because of the pressure from protests in China and from Chinese students and immigrants in France. Thus the May Fourth Movement ended in a victory, although the underlying situation in China had not changed. It remained a semi-feudal and semi-colonial country, suffering from poverty, imperialism and civil wars.

Role of students

Although the May Fourth Movement was initiated by students, it evolved into a nationwide mass movement. This underlines the role students can play as a catalyst to trigger movements by the much weightier forces of the working class, which was even the case in 1919 when the working class was still very small in relative terms.

It is a lesson often missed especially in the Chinese speaking world, where some political forces mistakenly see the students as the main force for change. Due to the inspiration of the May Fourth Movement the emergence of new workers’ organisations within the movement, the more active involvement of students in the workers’ struggles since then, and the establishment of the Communist Party shortly after the movement, the workers’ movement developed rapidly in China after 1919.

After the May Fourth Movement, many new workers’ organisations soon emerged including the ‘Secretariat of China Trade Unions” (the predecessor of the current official ‘trade union’ in China) which was established shortly after the birth of the CCP in 1921.

The number of strikes also increased significantly. There were 25 strikes in China in 1918 and 66 in 1919. In 1922, the Hong Kong seamen’s strike set off the first wave of nationwide strikes. There were more than 100 strikes and over 300,000 strikers that year. In 1923 and 1925, respectively, the February 7 Strike and Guangzhou and Hong Kong Strike took place, two significant strikes in China’s history.

After 1919, the Kuomintang as a bourgeois opposition party wanted to end warlordism in China, establish a united and independent national state and a stable capitalist system, and so it also actively intervened in the workers’ struggles, established some workers’ organisations and participated in the mobilisation of the Hong Kong seamen’s strike in 1922.

At that time, the Kuomintang’s involvement in establishing or supporting workers’ organisations was not primarily to advance the interests of the working class, but to build positions of support for the Kuomintang in its struggle against the Beijing government and other rival forces. For example, in the strike wave of 1922, strikes in the area controlled by the Kuomintang were suppressed and trade unions banned. However, in overall terms the Kuomintang’s involvement in workers’ struggles at that time acted as a spur to the development of the workers’ movement.

The level of development of workers’ struggles in China during the May Fourth Movement was still very low, and the Chinese bourgeoisie did not yet have a clear understanding of the threat to its own position from mass movements. This is another important reason for businessmen and merchants to organise a strike in June 1919.

Women’s movement

However, after the May Fourth Movement, with the further development of China’s working class struggle the bourgeoisie became more and more afraid.

In the anti-imperialist ‘May Thirtieth Movement’ of 1925 (which opened an unprecedented two-year revolutionary period in which the working class could have taken power), the Shanghai Chamber of Commerce agreed to cease trade only after they were forced to do so by the students and workers, and they were the first to surrender. The Shanghai Chamber of Commerce also helped the imperialists and warlord government to attack the workers who were still striking.

The May Fourth Movement also injected a strong impetus into the women’s movement in China. Women, especially working class women, are among the most oppressed groups and often stand at the forefront of mass struggles. Following the May Fourth Movement more and more women began to participate in social and political activities. In 1920, women in Changsha, Hunan province, joined a pro-democracy demonstration demanding free marriage and personal freedom.

A year later, also in Hunan, the ‘Federation of Women’ was established demanding equal rights to inheritance, votes, education and employment, as well as free marriage. In 1922, the ‘Feminist Movement Alliance’ established in Beijing not only demanded women’s rights but also called for democracy and the overthrow of warlord rule.

Divergence

Due to the May Fourth Movement and other mass struggles it inspired, the intellectuals who had united in the New Culture Movement soon split. In 1920, the Comintern sent its first representative to China to set up early Communist Party organisations together with Chen Duxiu and Li Dazhao, which also accelerated the division among young intellectuals.

Chen and the more radical youth more firmly turned to socialism, while bourgeois liberals retreated to a more conservative position. Although liberal intellectuals demanded democratic reforms and ending warlord autocracy, they opposed mass movements as the way to achieve these goals.

Lessons today

The Chinese bourgeoisie increasingly showed it could not lift the Chinese people out of the brutal oppression by imperialists, warlords, landlords and capitalists. Liberal ideas that were once warmly welcomed gradually lost support, while socialist ideas spread more widely.

In the May Fourth Movement, young students fearlessly confronted the autocratic regime of the warlords. The movement they initiated became a milestone in the history of mass struggle by Chinese workers. Today, 100 years later, leftist students and youth, including those from Peking University, bravely intervened in the Jasic workers’ struggle in Shenzhen, resulting in a severe crackdown by Xi Jinping’s regime.

More than 40 students, young people and workers are still being held by police with their whereabouts unknown, while Marxist societies are closed and banned on campuses around China.

Xi’s regime, which is facing political headwinds in China and internationally, is likely to use the May Fourth Memorial Day to drum up nationalist sentiment but of course to distort the truth about the May Fourth Movement in order to burnish the CCP’s credentials.

As the May Fourth Movement showed the struggles of students and young people can ignite broader mass movements and a workers’ movement, which is the decisive force in the struggle against dictatorship.

Socialist ideas

In the face of significant steps forward for workers’ struggles last year and the ‘sensitive’ anniversaries of this year, Xi’s regime will seems intent on using more violent suppression, but this will not extinguish the resistance of workers and youth. In the recent period a series of protests and strikes show a deepening radicalisation among China’s youth and workers.

Marxists look at the history of past struggles to draw conclusions for today and future struggles. The May Fourth Movement was transformational in terms of its effects on political consciousness and as a reference point for the battles that followed, of revolution and counterrevolution in the 1920s and 30s.

We are living in a period of similar tumultuous changes in which genuine socialist ideas can again become a mass force.