The Beijing massacre of 1989 crushed the democracy movement and cemented the Chinese regime’s embrace of capitalism

Dikang, chinaworker.info

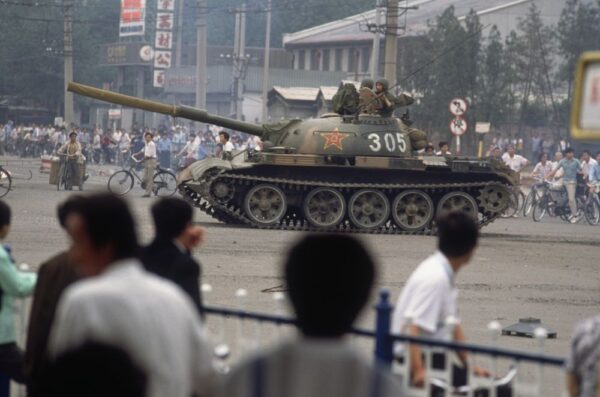

June 4 marks the 31st anniversary of the gruesome massacre in Beijing by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) on the orders of China’s top leaders. China was in the throes of a revolutionary mass movement. The mass demonstrations that burst out in April 1989 had paralysed Beijing for seven weeks and spread to more than 300 cities. This included many regional ‘Tiananmens’– huge movements in cities like Chengdu and Xian – with main squares also occupied and hundreds of thousands joining demonstrations.

Following the crackdown in Beijing on June 4, in which it is widely believed around 1,000 were killed, possibly many more, there were more deaths, injured and arrested in cities across China.

On the night of 3-4 June PLA tanks and armoured convoys began to shoot their way through the Chinese capital from four directions, meeting heroic mass resistance from the workers and ordinary citizens of Beijing, especially the youth.

“Kill those who should be killed”

The army’s invasion of the capital, with 200,000 troops (enough to invade a whole country), had been stopped in its tracks and forced to make camp in the suburbs, for an incredible fifteen days and nights by a mass mobilisation of Beijing’s working class and ordinary citizens. The top leaders had believed that just the show of military force would be enough to cower the masses and “restore order” i.e. the dictatorship’s shredded authority.

But the ingenuity and boldness of the masses blunted the initial military deployments. Soldiers did not want to attack the people. Army officers were split and unclear which forces within the regime were in control or what the leaders really wanted. The PLA juggernaut stalled, creating an even bigger crisis in the regime – this was a key reason why the violence was so extreme when it eventually came.

More than a million people participated in Beijing’s 15-day “human wall” as Chen Bo describes it in the book Seven Weeks that Shook the World (published by chinaworker.info – order from [email protected]), to block and engage with the PLA units. With all respect to the students, this was something much bigger than a “student movement”. A revolutionary struggle touching all layers of society was unfolding. American diplomats in Beijing complained that they had to send cars to pick up their Chinese counterparts in the CCP diplomatic compound, because the Chinese officials said their own drivers were on the streets demonstrating.

“Kill those who should be killed, sentence those who should be sentenced,” said Wang Zhen, a colonel in the army loyal to the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, the ultimate architect of the brutal crackdown. Deng had famously said he was prepared to order the deaths of 20,000 people if this would guarantee twenty years of stability in China.

These bloody events shaped the China of today, the world’s second most powerful capitalist economy, but with a nominally ‘Communist’ (CCP) regime at its head that refuses to countenance even the smallest democratic reforms and instead has increased state repression and political control to unprecedented levels in the past five years especially.

Some see this repression as the evil of Maoist ‘communism’ when in fact in China’s case the more capitalist it became, the more repressive it became also. As a 20-year-old Marxist activist involved in the struggle against the 2019 crackdown of left-wing students and worker activists told the Washington Post (25 May 2019), “Once you study Marxism, you know real socialism and China’s so-called socialism with Chinese characteristics are two different things. They sell fascism as socialism, like a street vendor passes off dog meat as lamb.”

The main role of the CCP’s supersized police state, with 10 million internet spies and a security budget on a par with Egypt’s GDP (1.24 trillion yuan or US$193 billion in 2017), is to prevent the working class from organising.

“Over the past 40 years in China we have had a creed of the market as a magic wand,” says labour activist Han Dongfang. “It is ironic that people are waving the communist flag but in fact the party is the biggest believer in capitalism, in the market and in jungle rule in the world.” [Financial Times, 24 May 2019]

Independent unions

Han was imprisoned after the June 4 massacre for his role as a pioneer of the independent trade unions that emerged during the mass struggle of 1989 and were the main target of the regime’s repression afterwards. While simultaneously attempting to blot out the role of the working class, the newly formed independent unions and the widespread strikes that featured in the last days of the 1989 movement, the CCP regime directed its most fearsome repression against the working class. The section of Tiananmen Square where the independent workers’ unions had their headquarters was also the section where the most bloody suppression occurred on June 4.

Read more ➳ China: lessons of 1989 mass democracy movement

Even the handful of top student activists on Beijing’s “most wanted” list in 1989 served at most two to three years in prison. That of course is bad enough. But of 20,000 arrested in the months after the crackdown, it’s estimated that 15,000 were workers, mostly charged with organising strikes (“sabotage”) and clandestine workers’ unions (“colluding with foreign forces”).

No students were executed but this fate befell dozens of workers, while others were given life sentences or many years of hard labour. An example is the ‘Shanghai Three’ who were executed after a brief trial on 21 June. Their ‘crime’ was to set fire to an empty railway carriage after the train had ploughed into a crowd of pro-democracy demonstrators blocking the track, killing six.

A student movement?

Most coverage of the 1989 movement describes it as a “student movement” which only gives part of the picture. The students ignited the struggle by marching to and later occupying Tiananmen Square. They showed many examples of heroism and audacity, but also had greater illusions in the CCP’s ‘reform’ wing around general secretary Zhao Ziyang.

Zhao favoured a gradual and limited democratic opening of China in contrast to more hardline leaders who wanted to fortify authoritarian rule and believed Zhao’s “bourgeois liberal” reforms, in reality very limited, had gone too far. Both sides were committed to continuing China’s transition to capitalism, their differences centred on the speed and degree of political opening that should accompany this.

What is omitted from most coverage of the Tiananmen events was the key role of the working class in China. The student protests had already peaked through exhaustion, with many activists drained by the mass hunger strikes that began in May.

The original student leaders drawn from Beijing’s more elite schools, with a stronger connection to parts of the CCP bureaucracy, were replaced by fresh layers often from outside Beijing and from more working class backgrounds. The students’ specific weight within the mass movement as a whole lessened as workers, and the working class youth of Beijing especially, began to play a more prominent role. This shift occurred most sharply when the army entered Beijing on May 20, following the declaration of martial law.

What began as a student protest movement aiming to bolster the CCP ‘reform’ wing and push back against the more authoritarian hardliners of its ‘old guard’, developed into a predominantly working class struggle with a more determined but not fully clear idea of defeating the CCP regime as a whole, without any special attachment to Zhao and his ‘reformist’ allies.

Unfortunately, there was no clear idea or strategy, no worked out programme of demands and steps to be taken, to carry this movement forward. While the student leaders who started the struggle had balked at going “too far” and wanted initially to keep workers out of the mass demonstrations (for fear of “provoking” the government), the fresher, more proletarian, layers that filled out the movement had no such reservations.

They saw the movement’s momentum was fast becoming a struggle of life and death, with the regime unprepared to make concessions. But what was lacking was a clear programme and a political organisation – a revolutionary socialist party – that could articulate the needs of the situation and re-orientate the mass movement in time.

Top-level splits

Zhao was decisively defeated in the power struggle that came to a crunch during the crisis of May 1989, over whether to offer concessions or use the army to put down the mass protests. This was a brutal power struggle (Zhao was put under house arrest until his death fifteen years later), which also explains why Deng and his cohorts unleashed such gratuitous and excessive violence on June 3-4.

This power struggle was not between pro- and anti-capitalist factions within the CCP-state – no section of the Chinese leadership advocated a return to the planned economy of the pre-reform era. It was a division between those who wanted to grant some democratic concessions to the protests and in so doing co-opt a section of the students and intellectuals into the regime, and those who favoured harsh repression to set a bloody example that the dictatorship’s authority could not be challenged. The latter line, favoured by Deng, prevailed and has been the hallmark of the Chinese regime ever since: capitalism combined with strict authoritarian control.

“There was a time in May 1989 when the government of China was overthrown as the real controlling authority” wrote A. M. Rosenthal in the New York Times on 23 May 1989. It is an accurate description. This writer, 31 years ago, made another very important observation: “Since no authority is available to step in, the Chinese government will probably be able to pull together what remains of its influence and summons the power to direct the nation once more.”

China in 1989 found itself in a fight to the death between revolution (the mass movement) and counter-revolution (Deng’s pro-capitalist regime). With the former failing to show an alternative form of government, to call for the mass movement to go further and build organs of popular power such as democratic committees, linked across the country, and for the workers now organising independent unions to take the lead in setting up a democratic workers’ and poor people’s government, the initiative of the mass struggle was lost.

Deng’s regime was able to regain its balance and strike hard. In doing so, it wanted to kill several birds with one stone. The workers’ organisations were the primary target, as well as clearing the streets of protestors with such ferocity as to send a signal that echoed across the country and through the ages. Another target of the bloody crackdown were the political reformers around Zhao, who had toyed with supporting or making concessions to the student protesters. The message of the crackdown was that while all wings of the CCP agreed on the need for more capitalist measures, ‘political reform’ and a Western-style ‘democracy’ were off the table.

This led not, as some commentators claimed, to the re-consolidation of a non-capitalist Stalinist regime, a social system that had already begun to break-up with the significant capitalist reforms of the previous decade. The dialectic of the situation was that the June 4 crackdown, allegedly to defend “socialism”, was a defining moment propelling the Chinese regime to complete the transition to capitalism although with rather unique Chinese characteristics. 1989 was a defeated political revolution, albeit one that had not fully articulated its aims.

Brutal capitalist restoration

China under Deng would continue on the road to capitalism, especially with his historic ‘Southern Tour’ of 1992, but this would be under the control of the authoritarian CCP-state to insure that the party elite and especially the ‘princelings’ – CCP royalty – could seize the juiciest pieces of the ascendant capitalist economy, while also maintaining iron political control to keep the working class down and nullify any resistance to brutal capitalist restoration.

Up to 60 million jobs were lost in the privatisation of state industries that reached a climax in the late 1990s. Permanent jobs were replaced by temporary and precarious contracts and agency work. China’s state sector today employs 60m agency workers on inferior pay and social benefits, more than its permanent workforce.

Housing was privatised in a ‘big bang’ reform in 1998, emulating Margaret Thatcher’s policies carried out on a smaller scale in England. Today, 95 percent of the Chinese housing market is homeowners, with only a minuscule social housing sector. This compares to 51 percent home ownership in Germany and 65 percent in the US. House prices have become a massive burden for working class and middle class Chinese. Beijing’s average house prices relative to average incomes are among the highest in the world, along with Shanghai and several other Chinese cities (twice as expensive as Tokyo and almost four times more expensive than London).

Read more ➳ China 1989: 25 Years Since the Mass Democracy Movement

Some onlookers mistake the high degree of state ownership of industry in China as a sign that it’s not ‘real’ capitalism, or that there is still some mix of different social systems. The state sectors of the economy, around 30 percent of GDP, including key sectors such as banking, energy, telecom and a significant presence in manufacturing, were used in the 1990s to create a capitalist class with the CCP officials’ relatives and friends guaranteed the best seats in the house.

This was exactly what Leon Trotsky, in his analysis of Stalinism, predicted would happen if, as in China 1989, a workers’ political revolution to establish democratic control over the state economy and government was unsuccessful:

“The political prognosis has an alternative character: either the bureaucracy, becoming ever more the organ of the world bourgeoisie in the workers’ state, will overthrow the new forms of property and plunge the country back to capitalism; or the working class will crush the bureaucracy and open the way to socialism.” [Trotsky, The Transitional Program 1938]

China’s authoritarian capitalism is based on fear of mass unrest and the insecurity of the capitalist elite, which largely hides its wealth from society with the help of unprecedented media controls and state propaganda. Its capitalist model is not US-style ‘democracy’ and ‘free markets’ but rather East Asia’s authoritarian capitalism with such examples as Chiang Kai-shek’s Taiwan, Lee Kuan Yew’s Singapore and Park Chung-hee’s South Korea. These were “fully” capitalist regimes with a largely state-controlled or state capitalist economy.

Recent credible media leaks suggest the family of president Xi Jinping, one of the CCP’s top ‘princelings’, have amassed US$1 trillion of wealth in overseas assets. Most members of China’s ruling Politburo are similarly mind-bogglingly rich. Not only does China have more dollar billionaires than the US, in the past year it has created three more Chinese billionaires for every new American billionaire.

Since Deng Xiaoping launched China upon the path of capitalist restoration in the late 1970s, the transfer of wealth from the poor majority to the super-rich elite has been greater in China than even in the US or Europe. From 1978-2015 China’s wealthiest one percent saw their share of national income increase by 8.6 percent per year, faster than the 3 percent growth in the US, and 1.4 percent growth in France, according to a study by the economist Thomas Piketty.

Hong Kong vigil

Unlike previous years, this year’s 31st anniversary commemorations will not see huge crowds gather in Hong Kong, the only city ruled by the CCP where demonstrations and remembrance of the June 4 massacre is tolerated. Last year the turnout was 180,000. The Covid-19 pandemic and social distancing laws that ban gatherings of more than eight people mean the historic trend is interrupted this year.

Smaller symbolic events will be staged around Hong Kong. But the memory of June 4 is not only kept alive, it can become an even more powerful factor because of the Chinese state’s seizure of direct political rule over the city with the enactment at last month’s NPC of the national security law. This sets the scene for more intense struggles in Hong Kong as the CCP regime seeks to crush the city’s democracy struggle.

Elsewhere the CCP’s repression continues to break records. Today’s gigantic censorship machine, which has reached astronomical proportions under Xi Jinping, was a critical reason why the initial coronavirus outbreak in December 2019 could not be effectively contained at the local level in Wuhan and became a global catastrophe. China has actually built one of the most advanced pandemic warning systems in the world but when it was actually needed this system was disabled by the censorship, false information, and cover-ups of the totalitarian state machine.

In the Muslim-majority region of Xinjiang, an entire population is being terrorised with more than a million incarcerated in concentration camps called “vocational training centres”. The entire region, half the size of India, has become a giant testing ground for a digital police state with cutting edge technologies like facial recognition surveillance systems, DNA harvesting and compulsory spyware in all cell phones.

The suppression of left-wing youth activists, students and workers in the aftermath of the Jasic workers’ struggle in southern China in 2018, while on a smaller scale, is an extremely important example of the worsening repression under Xi Jinping. These workers and youth were also wrongfully accused of “colluding with foreign forces” by state propaganda, a charge the CCP uses in Hong Kong and to denigrate every form of opposition.

While masquerading under the banner of ‘communism’ for historical reasons that in no way connect with its day-to-day policy, Xi’s regime has singled out Marxists and socialists as public enemy number one. This is against the background of heightened official nervousness, not lessened by the Tiananmen anniversary, and Xi’s warnings at the start of last year that China faces “unimaginable dangers”.

US-China Cold War

Recent years have seen a sharply escalating imperialist conflict between China and the US, which began over Donald Trump’s protectionist trade policies, and has rapidly spread to investments, technology, academic exchanges, geopolitics and military competition. This amounts to a new “Cold War” between the two superpowers, a naked power struggle to be number one, rather than a contest between incompatible socio-economic systems as was the case with the Cold War of the last century between Stalinist so-called ‘communism’ and capitalism.

Against this backdrop, based on divergent great power interests, China and the US have also begun to attack each other’s ‘human rights’ records – something we have not seen on any significant level for more than two decades. Chinese state media are revelling in Trump’s problems and providing saturation TV coverage of the mass protests against police violence in cities across the US. At the same time they twist and spread outright lies about the mass protests in Hong Kong. The US ruling class does the same thing in reverse: applauding protests in Hong Kong while describing demonstrators in the US as “terrorists”.

Privately, leading representatives of US capitalism endorsed the 1989 crackdown as an unpleasant ‘necessity’. Donald Trump has in the past expressed admiration for the CCP dictatorship’s “show of strength” in suppressing what he called a “riot”. George H. W. Bush’s government moved quickly but secretly in June 1989 to send National Security Advisor Brent Snowcroft to Beijing to reassure the CCP leadership that the limited US sanctions and official recriminations over the massacre would be temporary and Washington wanted to maintain its “engagement”.

A similar position was taken by the Thatcher government in Britain. British government documents declassified in 2017 showed that Prime Minister Thatcher and US president Bush agreed the West had important “strategic interests” to protect in China and should therefore not support the democracy protests which could “drive the Chinese into the arms of the Soviets.”

The Chinese regime similarly issued private assurances to Western governments to disregard its public attacks on “Western interference” and “alien influences”, which were necessary for propaganda purposes at home, and to be sure that the pro-capitalist policies of the previous decade would continue.

For Western capitalist leaders, economic gains and access for their companies are what really count, rather than lofty ideals about human rights and democracy. That this tone is now changing is part of a political propaganda game with the Chinese and US ruling classes wanting to burnish their own image and portray the other side as dangerous.

Learning the lessons

The lessons of the 1989 movement are crucial for building a future mass socialist alternative to capitalism in China and globally. The regime of Chinese Stalinism-Maoism which came out of the distorted revolution of 1949, had by the 1970s exhausted itself and was no longer able to develop the economy. Along with the other Stalinist bureaucratic dictatorships in Russia and Eastern Europe it entered a period of deep crisis with the top layers of the state seeing their only hopes for salvation in moving back to capitalism.

The nascent workers’ movement in China – obstructed by the strengthening of right-wing pro-capitalist ideas and leaders at the head of the Western labour movement – could not organise itself and clarify the necessary program in time to prevent the ‘communist’ bureaucracy destroying the planned economy and converting its own ranks into capitalists.

Read more ➳ Is China heading for a new Tiananmen?

Capitalism, while seemingly delivering spectacular GDP numbers in China’s case, has created unprecedented problems, massive inequality, unimaginable pollution, long working hours and stagnating real incomes. Social tensions in China are more extreme today than even in 1989. The pandemic-induced economic slump has resulted in one in five workers unemployed in China, with those still in work facing severe wage cuts. A new explosion of mass anger is brewing as recognised in the thinly disguised warnings of Xi and other top CCP officials.

As the left-wing youth who are now filling Xi Jinping’s arrest cells are showing, a new socialist labour movement is needed and is being created step-by-step in China. No amount of state repression can prevent this despite the terrible suffering the regime is meting out. A clear understanding of what went wrong in 1989, which allowed the butchers of Beijing to wriggle off the hook, is the best way to move forward and build a new mass movement against authoritarianism, capitalism and imperialism, with a workers’ party as its core.