The dominant group within the ruling party stand for continued but ‘smarter’ repression.

Here we republish this article which was first published 11 July 2011.

Despite the dictatorship’s triumphalist propaganda about its economic achievements, the reality is a deepening class polarisation and growing frustration and despair among vast numbers of poor over their own worsening situation. In Inner Mongolia for example, which produces a quarter of all China’s coal and possesses the largest share of wind power resources in the country, there are still 70,000 rural households without access to electricity. The wealth gap is extreme even within provinces – with per capita GDP in Guangdong’s richest prefecture (Shenzhen), ten times the level of the poorest (Heyuan).

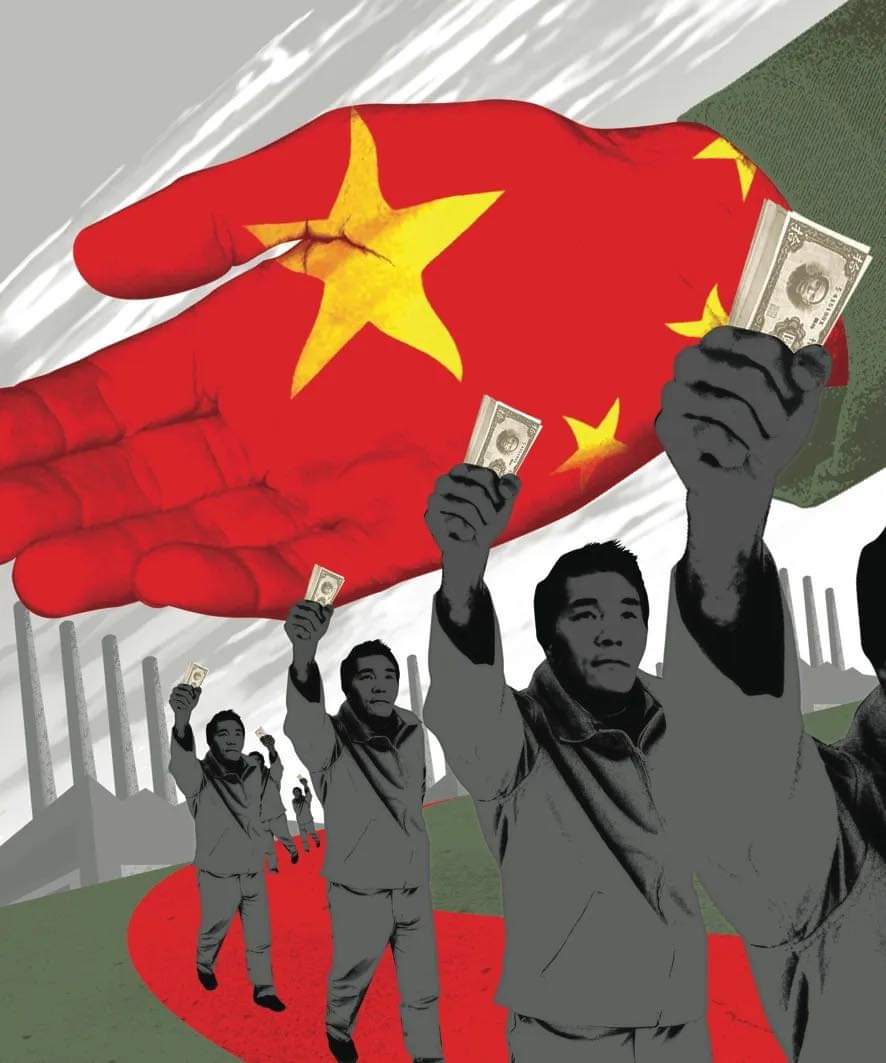

The puppet trade union body, All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU), revealed in a 2010 survey that the share of GDP going to wages declined by 20 basis points – from 56.5 percent in 1983, to 36.7 percent in 2005. The same report showed that “capital gains captured a 20 percent increase of share of the GDP pie in the same period” [Caijing magazine, 12 May 2010]. These figures confirm what socialists have consistently argued, that government policies of downsizing the SOE workforce (by more than 70 percent), crushing workers’ protests, and encouraging sweatshop production methods and conditions have resulted in a massive transfer of national wealth from labour to capital. According to the ACFTU, 23.4 percent of workers failed to get a raise in the past five years, with some 75.2 percent complaining about income inequality.

For years, dating back to the early part of the last decade, China’s leaders, with the support of global capitalist agencies like the IMF, have committed themselves to boosting domestic consumption in order to ‘rebalance’ the economy’s extreme dependence on investment and exports. This has not happened and in fact the economy has moved in the opposite direction, with investment – magnified by stimulus measures and massive amounts of credit – accounting for an unprecedented 50 percent of GDP this year. Consumption’s share of the overall economy is falling, from 46.4 percent in 2000 to 34 percent in 2010, and this trend is continuing today: the crippling cost of a new home is causing more and more urban households to save rather than spend, while inflation means that higher retail sales statistics disguise falling volumes. A major expansion of consumer spending, beyond a relatively affluent urban minority, i.e. the new middle-class, is not supported by real wage levels that are still very low, and hopelessly underfunded welfare provisions, which compel people to save a big part of their income.

The policies of the regime over two decades have fostered the growth of a super-rich class of capitalists and property owners. China now has 960,000 millionaires with personal wealth of 10 million yuan (US$1.54 million) or more. According to China Daily (April 15 2011), “55 percent of Chinese millionaires derive their wealth from private businesses, and 20 percent are property speculators who have ridden the fast hike in home prices”. The millionaires are without doubt the main beneficiaries of government policies and have acquired considerable economic power.

Increasingly, as the case of coal baron and NPC member Wang Chuncheng in Inner Mongolia shows, leading capitalists have been incorporated into governmental and semi-governmental structures, although in most cases this process has run in the opposite direction – top capitalists began as party officials and used their government positions to carve out business empires. According to an online poll conducted by China Daily, over 90 percent believe that the new rich acquired their wealth through “political connections”.

This is a process that was largely anticipated by the great Marxist revolutionary Leon Trotsky, who warned that the Stalinist bureaucracy that rose to power over the planned economy in Russia, following defeats for the international working class in the 1920s and 30s, would increasingly threaten the social gains of the revolution and state-owned economy, unless it was overthrown by the working class in a political revolution. Trotsky, in his brilliant analysis of Stalinism, The Revolution Betrayed, explained how a bureaucracy resting on a nationalised economy could, if it succeeded in breaking the resistance of the working class, develop into a capitalist class: “It is not enough to be the director of a trust; it is necessary to be a stockholder. The victory of the bureaucracy in this decisive sphere would mean its conversion into a new possessing class.”

Changing role of the party-state

In China this process has occurred within the framework of the former Maoist-Stalinist ruling party, which has morphed as a result of explosive capitalist growth into an instrument for the country’s new economic rulers, based on new property relations and the break-up of the old planned system. This outcome grew out of a series of setbacks internationally for the working class movement, rooted in the lack of truly socialist mass parties, which gave rise to a temporary consolidation of capitalism on a world scale, despite its economic contradictions, especially over the period since the early 1990s, when the Stalinist USSR collapsed, and until the recent global crisis. The processes in China also played a decisive role in this period of accelerated capitalist globalisation.

Today, as Wikileaks reported, quoting a leaked US government cable, “China’s ruling Politburo is a cabal of business empires that puts vested interests over the needs of the poor and curtails media freedoms to avoid having shady business deals exposed in the press”. This report noted that it is “well known” inside China that former premier Li Peng and his family controlled the country’s electric power industry, while the security chief Zhou Yongkang controlled the oil sector and the wife of premier Wen Jiabao, Zhang Peili, controls the precious gems sector. This represents a qualitative transformation from the situation before, under the Maoist-Stalinist regime in which, for sure, state officials also engaged in corruption and enjoyed great privileges due to their positions in the governmental hierarchy.

But the planned and fully state-owned economy, even the bureaucratically distorted and totalitarian version that paraded as ‘socialism’ under Mao, imposed limits on this process – limits that have been blown away by China’s capitalist development. This was because state property, no matter how much the bureaucrats stole, could not be ‘legimatised’ and converted into private property, ownership of companies, stocks, and financial assets. Today, these barriers have been removed, with the leaders of the ‘Communist Party’ personally leading the way, enriching their families and amassing huge business interests. The party has become a crucial mechanism for them to protect their wealth and economic positions in the new economy, and also to obscure the full extent of this from society at large. Similarly, the party, as a secretive and hierarchical organisation, is well suited to the role of ‘horse-trading’ and mediating in conflicts of interest between different branches of economy, provincial rivalries and competing business ‘clans’.

The form of capitalism specific to China is a peculiar form of state capitalism, which for material and historical reasons has significant differences from capitalism in the older industrialised states, although there are similarities with some other East Asian states. It favours one-party dictatorial rule to maintain control in a vast, complex and unstable society, and especially to hold down the working class and rural masses.

Inevitably this has given rise to rampant corruption. Last year, 146,500 officials were punished for corruption, but fewer than 3.5 percent of these cases were above county-level rank. Much ‘bigger fish’ have been let off the hook, and this is not accidental. It is precisely because the party-state has, with the explosive economic development, become an amalgamation of rival ‘centres’ – business groups and provincial cliques – as well as factions. Corruption cases against senior officials, which are rare events, must usually be prepared by exhaustive factional negotiations to avoid triggering ‘instability’ and open feuds within the ruling apparatus. Crooked officials are protected by factional ties, and the factions keep tabs on each other’s not-so-legal activities.

Corruption increasingly takes place through ‘clusters’ of officials in a given locality acting in league with local capitalists. Few disciplinary cases go to legal process, with the majority being dealt with in secret through the Communist Party’s own internal disciplinary system, ‘shuang gui’, with its backroom deals and factional string-pulling. Keeping corrupt officials out of the courts prevents them from blabbing their mouths off, and thus keeps the true scale of official abuse and looting out of the public eye. Roughly four-fifths of cases referred to ‘shuang gui’ are never passed on to the public prosecution system. The net result of this is that the government’s anti-corruption measures are extremely ineffectual – “much thunder but little rain” – further corroding the state’s authority among the masses. One top official summed up the dilemma for China’s rulers: “Fight corruption too little and destroy the country, fight it too much and destroy the party.”

This reality was underlined by recent revelations, in a report by the central bank, that up to 18,000 officials and SOE executives have fled abroad or gone missing, pilfering nearly 800 billion yuan (US$123 billion) since the middle of the 1990s. The figures themselves are sensational, but perhaps even more telling is the fact that the award-winning 67-page report was removed from the bank’s website within days. Government officials and media have dismissed this report as “inaccurate” without suggesting any alternative figures. This is not the only instance where major state institutions countermand each other. The ‘state’ in China is not one whole, but a composite of increasingly ‘inharmonious’ competing entities. This is especially true of the relationship between lower-level governments and the centre.

The economist Andy Xie estimates that around ten percent of China’s GDP is swallowed up by corruption or so-called grey income. He warns that this serves to “cut economic efficiency massively, create unsustainable social inequality and sow the seeds of revolution.” [South China Morning Post, 8 July 2011]

In the shift from a planned economy to capitalism with ‘Chinese characteristics’, the so-called Communist Party (CCP) has sought to create new bases of support in society – the bourgeoisie, the urban middle classes, public servants and to some extent also the workforce of the much-downsized SOE sector. These skilled workers and salaried staff have some features of a ‘labour aristocracy’. Their ‘loyalty’ to the ruling group, which has yet to be tested in a serious economic crisis, has been based on continued GDP growth and partly bought with policies to encourage home ownership (the main form of investing savings as a hedge against inflation) and by conferring certain ‘privileges’ not available to the masses especially of rural China.

The propaganda of the regime plays upon fears of ‘instability’ – and the idea that things could get significantly worse in the event of regime change – as well as nationalism and the triumphalist message of China’s rise in the world. But this new social base of the regime could be seriously eroded in an economic crisis, induced by world events or the bursting of today’s gigantic speculative bubbles in property and commodities.

Such are the internal contradictions within the Chinese party-state, that its room for manoeuvre is more circumscribed than many commentators imagine. This is true both on the political and economic plains.

Hukou reform?

A good example of the regime’s limited room for manoeuvre is the issue of ‘reforming’ the iniquitous hukou (household registration) system, which excludes migrants even after many years of residence, from access to housing, healthcare and schooling in the cities where they live. As the basis for the discrimination of China’s 200m migrants, the hukou system has been a major trigger of social unrest in the recent period, as witnessed by events in Guangdong. Local governments have introduced selective reforms, such as ‘points systems’, similar to the US ‘green card’, to allow a relatively small number of skilled migrants needed by local companies to escape the curse of their ‘second class’ rural hukou. But the same local governments do not want to shoulder the costs of a major expansion of healthcare, transport, schooling and social services, which would be needed if the hukou system were abolished. This would mean raising local taxes, which in turn would put upward pressure on wages and eat into the profits of the employers.

A recent study by a government think-tank concluded that “urbanising” migrants so that they gain access to schooling and welfare roughly in line with today’s city-hukou holders, would cost about 80,000 yuan (US$12,340) for each migrant. Based on government projections of 15 million rural inhabitants migrating to cities every year, this puts the cost of abolishing hukou at an astronomical 1.2 trillion yuan (US$185 billion ) just for one year’s intake of new migrants. As local governments must shoulder this bill, with central government funding only a small share of education and healthcare budgets, they show little enthusiasm for wholesale reform of the system.

This has been debated by the regime for almost two decades without issue. When 13 newspapers dared to publish a coordinated editorial in March 2010 calling for hukou reform, the propaganda department cracked down with disciplinary measures and threats against the editors. Their ‘sin’ was to raise this issue not in the form of a think-tank report for an inner circle, but in the public domain.

One of the effects of the post-2008 economic stimulus has been an unprecedented infrastructure boom in poorer inland provinces. This largely debt-financed boom, driven by local governments and their shady ‘off-balance-sheet vehicles’, has changed the pattern of rural-urban migration in China, with more migrants electing to stay in their home province where jobs are now easier to find.

As a consequence several coastal provinces are experiencing labour shortages and this is a major factor forcing them to increase minimum wage rates. There is also, correspondingly, a ‘reverse migration’ of low-tech and labour intensive factories into inland provinces where labour is still plentiful and cheaper. Local governments compete for this industrial relocation, offering cheap or free land, factory buildings, commandeering of labour, tax breaks, and numerous other sweeteners.

While migrant wages are still very low, and companies have increased exploitation, piecework etc., to offset the rise in minimum wages, the labour shortage has given workers greater bargaining power, which is reflected in a more combative mood. The spread of industrialisation to inland provinces will soon be manifested politically as well as economically. Strikes in these regions could have a very different character, where workers are not isolated – in factory barracks, speaking a different dialect to locals – but are rooted in these communities. The basis for solidarity action and for strikes to spread to other areas will undoubtedly be strengthened by this development.

‘Red Culture’?

“Whereas the outside world regards China’s rulers as all-powerful, the rulers themselves detect threats at every turn.” So commented The Economist (14 April 2011), in a – for once – accurate description of realities in China.

The central government must always strike a delicate balance between the various contending forces not only in society at large, but also within the ruling party and state. China manifests a peculiar form of ‘Bonapartism’ – by committee, rather than in the person of a ‘strongman’. This too is not accidental. The experience of Mao’s rule and also Deng Xiaoping’s, with erratic swings and accompanying social upheavals, produced the current ‘compromise’ system, in which the powers of the leading group are subject to ‘checks and balances’, realised through an exhaustive process of negotiations and trade-offs between factions, provincial governments and business-based clans.

The problem with this formula for government is that, just as serious social and political problems are accumulating, the government’s real freedom of action – beyond mere speeches – can be limited. This explains why numerous ‘central policy aims’ such as cutting energy intensity and pollution, increasing household consumption, halting illegal land sales, increasing education spending, curbing corruption, etc., have proven illusive.

But what about the massive stimulus programme – didn’t this represent a bold turn by the government? Yes, but while in one sense showing the power of the central government, this was largely a case of removing controls – allowing banks, state-owned companies and especially local governments to contract massive loans with an implicit central government guarantee – rather than attempting to control or guide developments. The truth is that this process was largely uncontrolled – even uncontrollable – as shown by current efforts to rein in credit and overinvestment. The full effects of this unrestrained credit expansion are still working their way through the economy, with potentially disastrous consequences. Despite this, more stimulus measures are highly likely in the event of a new economic downturn, in order to buy time for the regime, regardless of the long-term effects

Behind the veneer of ‘party unity’ there are growing divisions within the regime. This does not signify the emergence of anti-capitalist versus capitalist factions. Even the small Maoist rump within the ruling party does not advocate a return to economic planning. A more significant struggle is between ‘neo authoritarians’ who want to ‘perfect’ the current repressive system, and those, only a small minority today, who support more Western-orientated ‘democratic’ forms of government. Marxists must carefully analyse these shifts and signs of internal conflict within the state, in order to work out perspectives. While harbouring no illusions, the nascent workers’ movement can exploit divisions in the ruling group to advance its own positions.

One example is the ‘red culture’ campaign launched by Chongqing party boss, Bo Xilai. Bo’s campaign, launched in 2009, aims firstly to boost his own standing as an ‘audacious’ and ‘popular’ leader, but also to buttress the party’s standing in the face of crumbling support and the all-pervasive stink of corruption.

This campaign has revived some of the rituals and trappings of Maoism, but without Mao’s propensity to lean on the masses and preach ‘class struggle’. It consists of the singing of ‘revolutionary songs’ and other stage-managed events, conferences and lectures. Mistakenly encouraged by Bo’s campaign, some grassroots Maoists have tried, sporadically, to organise their own public events and sing-alongs, but have been immediately suppressed. The Maoist Communist Party (an underground group) organised a conference in Chongqing in 2009, believing this would be tolerated in this capital of the ‘red culture’ campaign, but all the participants were arrested on Bo’s orders and eight of them still languish in prison.

There is no anti-capitalist or radical element in the ‘red culture’ movement, which was mainly launched to enhance Bo’s chances to capture a seat in the Standing Committee of the Politburo next year. There is, however, a very strong authoritarian element, and Bo’s supporters are poles apart from the ‘political reform’ wing around premier Wen, which favours a gradual and partial lifting of repressive controls. Still, the campaign of Bo is an important development signifying that the relative cohesion of the ruling group – in public at least – since the 1989 Beijing massacre is beginning to unravel.

The ‘red culture’ campaign has since been adopted by the national leadership, with differing degrees of enthusiasm. It stresses nationalism and China’s dependence on the CCP as the only force to develop society. An additional element in the campaign exalts the ‘purity’ of the revolutionary era, in an attempt to check uncontrolled corruption. Bo himself is an archetypal representative of the new generation of Chinese rulers, especially the arrogant ‘princelings’. Both in Chongqing and in his earlier tenure as mayor of Dalian, Bo has brought in huge amounts of foreign capitalist investment and encouraged private business. In 2002, as provincial governor in Liaoning, Bo oversaw the crushing of mass worker unrest. This movement is quite famous, one of the most important attempts by workers to establish independent trade unions, and chinaworker.info long campaigned for the release from prison of two workers’ leaders, Xiao Yunliang and Yao Fuxin, victims of Bo’s crackdown.

There are ‘social’ aspects to Bo’s policies in Chongqing, but these are limited. One is the building of ‘social housing’ at controlled rather than market prices for lower income households. But the majority of these housing projects are for sale, not for rental, which is the most pressing need for the poorest sectors of the population. The scheme is financed by selling state-owned land. Another scheme launched by the Chongqing government allows farmers to obtain city hukou papers in return for selling their land. This has proved popular, but brings clear commercial benefits to the government and the property tycoons.

Chongqing’s mayor, and Bo sidekick, Huang Qifan, said of these policies: “We are pursuing the Reagan-Thatcher model of the 1980s. During a time of economic crisis, we think that people should be given money so that they will spend it. If business is good, employment will be low and people will be better off.” [FurureGov, 4 July 2010]

In contrast to the Maoists, some of whom – at least initially – saw in Bo’s policies a possible break with the capitalist policies of the central government, the supporters of Marxism and chinaworker.info explained this was not the case. The adoption of some Mao-era rituals shows that Bo, and later Beijing, have understood this can to some extent cut across the regime’s deepening unpopularity and get an echo among certain layers of workers and youth, but for the emergence of a genuine political alternative to capitalism we must look outside the putrified business-dominated structures of the CCP.

Commenting on the red culture campaign and state-sponsored nostalgia, He Bing of the China University of Politics and Law, argued, “They encourage you to sing revolutionary songs, but do not encourage you to make a revolution; they encourage you to watch [the new film] ‘The Great Achievement of Founding the Party’, but they do not encourage you to establish a party.”

This film, incidentally, timed for the Communist Party’s 90th anniversary, is sponsored by General Motors!

‘The Great Achievement of Founding the Party’ film poster

Political reform?

Such is the peculiar nature of the Chinese regime and its extraordinary internal complexity, that despite the warning signs and a rising curve of instability, there has been no relaxation of authoritarian controls and rather, at present, a marked shift in the opposite direction. This does not mean that the regime cannot be forced to adopt a new course by circumstances – by a massive regime-threatening outbreak of mass struggle. But a shift towards ‘democratic’ concessions and a lifting of authoritarian controls under such conditions may well come too late to save the regime.

Wang Changjiang, a senior scholar at the CCP’s top training academy, complains of a “phobia of political reform”. By far the dominant group – or coalition of groups – within the leadership stand for the line of continued but ‘smarter’ repression. They oppose any loosening of political controls fearing this would lead to greater social unrest and protest, regional conflicts, and splits in the state machine (since 1989 especially, factional struggles have been kept hidden from the masses). And not least the powerful industrial and financial groups within the ruling party fear their loss of economic privileges and monopoly controls should the party’s grip on power be loosened.

The repeated and extremely vague calls by premier Wen Jiabao for political reform, most recently aired at a meeting in London, have not produced one concrete policy. This is despite the fact that Wen’s ideas do not amount to any far-reaching shake-up of the political system. He has attacked “excessive concentration of power and lack of checks on power”, but his remedy is a more clearly defined and independent legal system (‘rule of law’) and greater leeway for the media, rather than empowering the masses with the right to vote or organise. Wen’s ideas reflect the demands of small and medium capitalists, and foreign investors, who want more legal protection against copyright theft and greater ‘transparency’ in the tendering process for government contracts, for example, but do not want to deal with independent unions and an unshackled working class.

Wen and the reform wing want, with the help of some carefully positioned ‘safety valves’, to strengthen the one-party system, not to replace it. They also want to strengthen the relative position of private companies, partly through legal reform and a freer media, as a means to increase competitive pressure on SOEs to use capital more efficiently. Socialists of course reject such arguments pointing to international experience with ‘anti-monopoly’ measures and ‘deregulation’, which has only benefited new capitalist combinations but not the masses. We point to democratic workers’ management and control of industry as the only way to achieve real efficiency in the public interest.

Although his wing is heavily outnumbered within the ruling group, Wen is allowed a certain license to air his ideas especially on foreign trips (his speeches are not always reported at home). This is partly a sop to the reformers and their supporters, holding alive their hopes for political reform despite all the evidence to the contrary, and partly also to reassure foreign governments and audiences by giving the same misleading impression. Media and legal ‘reforms’ are favourite themes for foreign middle-class liberals and capitalist investors respectively, rather than workers’ rights and real democratic change.

Socialists warn against any illusions in a process of regime-led ‘political reform’ or ‘democratisation’. Just as we also warn against the idea that democracy will emerge spontaneously as a result of more capitalist development in China. Democratic rights can only be realised through mass struggle, and the working class – organised around the programme of socialism – is the main force to achieve this, drawing other oppressed classes to its side.

Inevitably from the upheavals that are increasing in regularity and intensity, new organisations of workers and poor farmers will emerge and learn how to defend themselves and their independence from state repression. The political consciousness of workers and youth will also be shaped by the deepening realisation that there is no way out under the dictatorship.

The economic stimulus policies, applauded by capitalist agencies like the IMF and G20, averted an immediate slump in 2008-9, but failed to address any of the fundamental problems of the economy. Instead they increased the economy’s dependence on debt-driven investment and a build-up of destabilising inflationary bubbles, which workers and the poor are paying for.

At some stage, therefore, the most likely perspective for China is a massive social explosion on a scale that could even put recent events in the Middle East into the shade. Timescales are impossible to predict in politics, but this is the general direction.