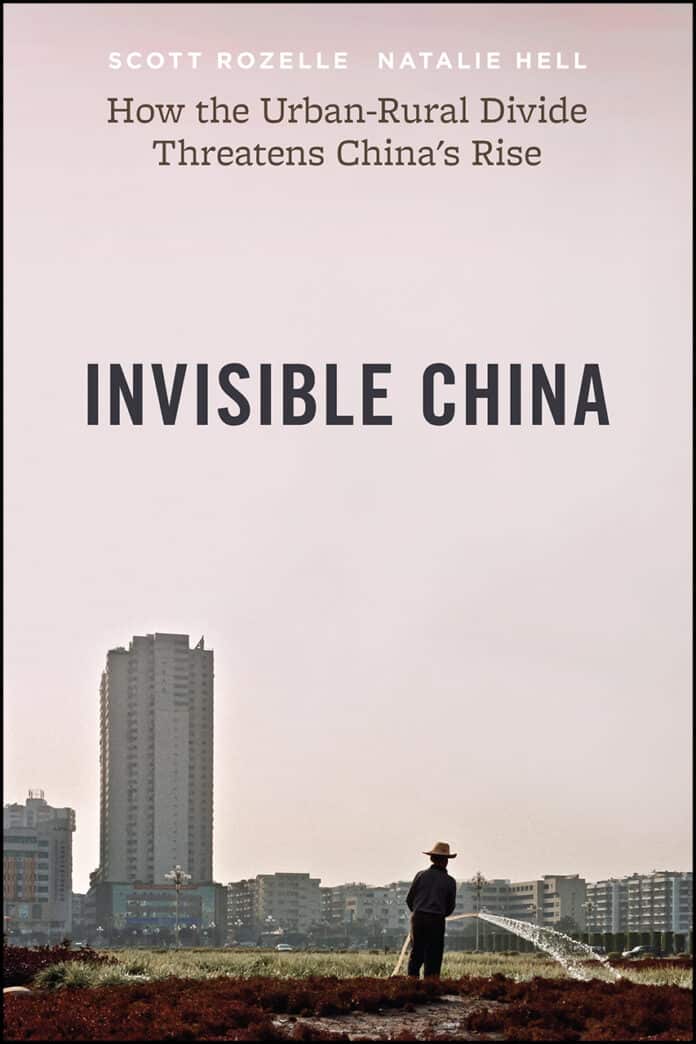

Invisible China: How the Urban-Rural Divide Threatens China’s Rise by Scott Rozelle and Natalie Hell reviewed by Vincent Kolo

“Why would I talk to my baby?” a young mother in rural China giggled at the question. “She can’t talk back!” Scott Rozelle, who has written this book together with Natalie Hell, has spent more than 30 years researching China’s labour force and its rural-urban divide. He recounts how village parents reacted with puzzlement and even laughter when he asked if they talked or read stories to their babies.

“You see, the baby can’t understand words. He can’t even follow simple instructions like ‘don’t go outside.’ So how could he follow a story?” one grandmother explained, amazed at the question’s stupidity. This is the reality in rural China which still lags far behind its modern cities economically and socially. A study on rural parenting by the authors found that only 5 percent ever read to their children, only ten percent told their babies stories, only 30 percent used toys to play or sing to their children. “This problem is systemic across villages in the Invisible China”, they say, pointing to an “infant development crisis” in the country.

Rural poverty

For context we need to see that rural China is still mired in poverty and has been plundered of resources and manpower to fuel the development of Chinese capitalism. This is especially the case with the mass migration of the younger generation to work as migrant labourers in China’s cities. More than 70 million people in the countryside live on less than one US dollar a day, according to the World Bank. Childcare and preschool services in China are mostly privately-run and expensive. Only around one-fifth of childcare is local government-run. For most rural families it simply doesn’t exist.

Many villages are populated only by the elderly and children. There are 60 million “left-behind” children, separated from one or both parents for long periods due to migration. Most of China’s 280 million migrant factory and construction workers go home to their villages once a year for the Chinese New Year holiday. As the authors point out, a fairly common sight in the countryside is a grandmother working in the field with a baby strapped to her back. “The baby is close to Grandma, safe and warm, but immobilised and staring up at the back of her head for hours on end with no mental stimulation or social interaction.”

30 million more words

Similar problems arise in every capitalist society. US research has shown that babies in rich families hear 30 million more words in the first three years of life than babies in poor families. The class divide for newborns is even more extreme in China. The poverty of rural – what the authors call “invisible” – China has created an educational and economic time bomb. Rozelle and Hell call this “the single greatest crisis China faces today”.

According to their findings, “at least half the children in China’s rural villages are scoring low enough on cognitive tests that it is unlikely that (without immediate intervention) they will ever reach adult IQs above ninety. IQ is scaled such that an IQ of ninety or less puts the bearer in the lowest 16 percent of a normal population.”

Too sick to study

Most people familiar with China know that it is now a predominantly urban society – almost 65 percent of the population live in cities. But as Rozelle and Hell point out, more than 70 percent of children are born with a rural hukou. This is China’s apartheid-like household registration system, which divides the population into urban (“first class”) and rural (“second class”) citizens. This staggering statistic means that over two-thirds of China’s future labour force is growing up facing massive and systemic educational disadvantage. By the fourth grade, rural primary school students were more than two grade levels behind their urban counterparts in math, according to a study in central China. The book explains how, while the government has poured billions into education, including modernising most rural schools, this has not really solved anything because it does not address the root cause. This is not just about new school buildings and higher teachers’ salaries, but the impact of lifelong poverty, demographic distortions and the lack of even basic welfare provision.

The latter is inextricably tied to the crisis of infant development and education. “Simply put, rural children are not learning because they are sick,” they explain. Over half China’s rural babies are undernourished, Rozelle’s research teams found, while more than 30 percent of children in grades four to eight have vision problems but do not have glasses. This is two to three times higher than the rate of poor vision in other countries.

Capitalist restoration

A third and perhaps even more shocking “invisible epidemic” identified by the authors is the prevalence of intestinal worms in rural children. In Guizhou province, one of the poorest, 40 percent of pupils in rural elementary schools were infected with parasitic intestinal worms, according to a provincial level study in 2013. Similar rates of 40 percent or higher were reported in rural areas of Sichuan, Fujian, Hunan and Yunnan. Worms lead to malnutrition, dizziness and compromised physical and cognitive development. In China it was the case until the 1980s that schoolchildren were dewormed at school twice every year with the use of drugs. But this has been discontinued. While the authors don’t mention this, the timing is conspicuous – one of many examples of the effects of capitalist restoration and the collapse of rural healthcare and social services that accompanied it.

While China’s city population enjoy educational attainment levels that are as good or better than in the US and other Western countries, rural students – the majority – are falling behind. This means that only 12.5 percent of China’s labour force has a college education and only 30 percent has completed high school, according to the 2015 national microcensus. This puts China squarely behind all other middle-income countries including Mexico, Thailand and South Africa. The book warns this educational black hole could shipwreck the Chinese regime’s ambition to attain advanced economy status.