Gigantic Belt and Road infrastructure plan – spearhead for Chinese dictatorship’s economic and geopolitical strategy

Vincent Kolo, chinaworker.info

The gigantic Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has assumed increasing importance for the regime of China’s ‘strongman’ Xi Jinping. The BRI, also known as OBOR (One Belt One Road), is “the world’s biggest building project” according to the Guardian newspaper.

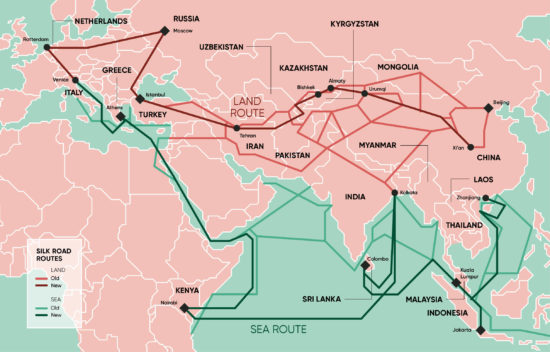

It’s ambition is to link more than 65 countries with a combined 4.5 billion people – three times China’s population – and spanning every continent bar the Americas into a China-led economic sphere. This is to be achieved through the construction of a series of vast “economic co-operation corridors” comprising fuel pipelines, highways, ports, railways, transnational electric grids and even fibre optic systems.

‘Polar Silk Road’

As part of the so-called ‘Communist’ (CCP) dictatorship’s propaganda, the BRI is pitched as a modern version of the ancient Silk Road trade routes linking East and West. In fact, the geographical scope of the BRI goes far beyond this. Iceland, Greenland, Scandinavia and the Arctic region are also being incorporated into the Belt and Road scheme with plans for a ‘Polar Silk Road’. The Arctic is one of the last remaining frontiers for large-scale gas and oil extraction, and a new shipping route as global warming destroys the ice cover.

At the showcase BRI summit held in Beijing in May 2017, with 130 countries sending representatives, Xi Jinping pledged to “build a big family with harmonious co-existence.” The BRI would mean a new “golden age” of globalisation, he said. In reality, however, the BRI is an expression of the explosive emergence of China as a new global imperialist power vying with its older rivals, chiefly the US, to secure spheres of economic influence and control.

China’s economy has outgrown its national limits. In a global capitalist economy still reeling from the effects of a ten-year-old crisis, with ‘de-globalisation’ on the front foot as each capitalist government tries to protect its own economic interests, the Chinese regime fears being shut out of key markets.

The still relatively low level of Chinese wages and skyrocketing costs for housing, healthcare and education act to repress domestic demand. Consumer spending accounted for only 39.2 percent of GDP in 2016, despite government claims that a successful transition is taking place away from investment towards consumption as a growth driver. China’s level of consumption as a share of GDP is very low by international standards and lower than in China in the 1960s.

“Hard landing”

China’s crisis of overcapacity is a major reason for the BRI. Vast numbers of so-called “zombie” companies that have no market to sell into are kept alive by soaring levels of debt. In recent years the Chinese regime has used massive infrastructure investment to ward off a sharp drop in economic growth – a “hard landing” – which it fears would trigger mass unrest. But this option is becoming increasingly problematic as more and more infrastructure projects are underutilised (ghost cities and white elephants) which puts further stress on a shaky financial system.

The CCP regime therefore sees the BRI as a saviour, to create new markets for its hulking infrastructure companies – markets which are then tied to China’s economy through debt dependency. This is why the CCP took the extraordinary step of writing the requirement to “pursue the Belt and Road Initiative” into its party constitution at the 19th Congress in October. Xi Jinping has done this to show that the BRI is irreversible.

The only other example of a specific foreign policy initiative being accorded such status is Deng Xiaoping’s pro-capitalist “reform and opening” policy which was launched 40 years ago, in 1978, and enshrined in the party constitution in the 1980s.

Imperialism

Describing imperialism in his incisive analysis published over a century ago, Lenin pointed to “the struggle for the sources of raw materials, for the export of capital, for spheres of influence, i.e., for spheres for profitable deals, concessions, monopoly profits and so on, economic territory in general.” (Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism).

The Economic Times, admittedly reflecting the view of India, a rival Asian imperialist power, gave a succinct description of how China’s state-financed imperialism works: “China’s strategy to grab land and assets in smaller, less-developed countries is simple: it gives them loans on high rates for infrastructural projects, gets equity into projects, and when the country is unable to repay the loan, it gets ownership of the project.”

Not inaccurately, China’s actions are described as “creditor imperialism” by Brahma Chellaney, an advisor to the New Delhi government. A clear example is what has just happened in Sri Lanka, where China has secured ownership on a 99-year lease of the Hambantota port, which was built with Chinese loans.

The port has geopolitical significance by virtue of its location at the tip of the South Asian subcontinent. Chinese companies and loans have built so much questionable infrastructure in Sri Lanka, including the “world’s emptiest airport” also at Hambantota, that tour companies are running “white elephant tours” of the area.

In Pakistan, the country with most BRI-linked Chinese investments at this stage, a political power struggle between the army and civilian politicians is raging over similar Chinese actions. A recent critical report by the Pakistani Senate reveals that China will for the next 40 years get 91 percent of the revenues generated by the deepwater port of Gwadar on the Arabian Sea, which was built using Chinese companies and loans.

Gwadar, like Hambantota 2,700 kilometres to the south, represents not just a shipping hub but also a military-strategic asset for China in the event of a future regional or global conflict. The Pakistani state’s rule in Balochistan where Gwadar is located is marked by extreme brutality. Other BRI-linked projects from Myanmar to Indonesia are aggravating national and ethnic tensions, ravaging the environment and evicting local communities.

The big increase in Chinese investments and infrastructure deals in South Asia especially is fuelling a geopolitical tug-of-war with India, the main obstacle and counterweight to the BRI and China’s growing presence. The US weighs in on India’s side and Trump recently revived its Quadrilateral Security Dialogue or “Quad” alliance with India, Japan and Australia to push back against China’s expansion.

Workers’ organisations and the left need to be politically independent and not get sucked into supporting any of these feuding governments with their hypocritical attacks on each others’ imperialist schemes. Only internationalism and struggle against all national strains of capitalist exploitation offer a way forward for the masses.

Sharpening conflicts

Clearly, there are special features in China’s variant of imperialism. This is shown in the case of the BRI, firstly in terms of size. The scale of the BRI is gargantuan – if it can actually be realised. Secondly, it aims to repeat key features that distinguish China’s domestic growth model, powered by credit from the state-owned banking sector.

This model has allowed China to rapidly industrialise and upgrade its infrastructure, but has also led to its monumental and – according even to the Chinese government – unsustainable debt problem. Beijing hopes to disperse this debt burden to other countries through BRI-linked loans. China’s financial elite see this as a way to cut the banking system’s exposure to heavily-indebted “zombie” companies at home.

They set up the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) in 2016 as an auxiliary to the BRI in order to draw in Western capitalist states (61 countries have joined including Britain, Germany and France) and harness their financial “expertise”. This has been done to shape AIIB/BRI lending practises along more traditional capitalist lines, as with US-dominated institutions like the World Bank and IMF, and thereby reduce the risk of debt defaults. Or so Beijing believes.

BRI projects, they hope, will replace China’s local bad debts with sovereign debt, guaranteed by national governments. But more likely this will just replicate China’s “zombie” predicament on an intercontinental scale, while also sharpening national and inter-imperialist conflicts.