Local government debt has soared but Beijing’s attempt to curb runaway credit misfires again

Vincent Kolo, chinaworker.info

An end-of year scramble for funds by financial institutions drove up interbank lending rates to levels not seen since the June liquidity crisis, threatening turmoil in money markets and triggering the longest fall on the domestic stock market for almost 20 years. While the crisis may have been averted this time around, following intervention by the central bank on Tuesday 24 December, it highlights the precarious state of China’s banking system, perched upon a growing mountain of debt. This is the legacy of the gigantic 2009 stimulus package and the Chinese regime’s failed attempts to ‘game’ the capitalist system through state-funded interventions. The latest ‘reform’ plans of the ruling ‘Communist’ dictatorship (CCP) – in reality a massive package of neo-liberal counter-reforms to bolster capitalism – threaten to hasten the very financial crisis they are trying desperately to avoid.

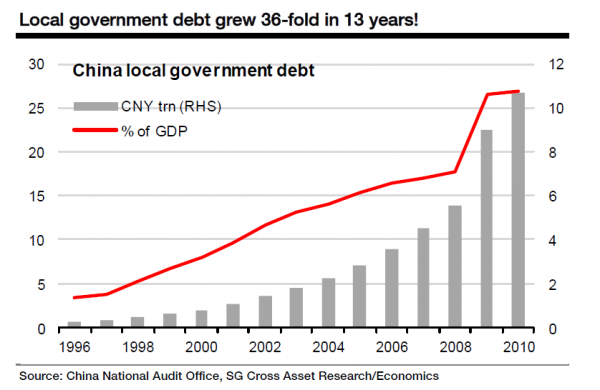

A key focus of the current financial malaise is the debt burden of local governments, described as the “Achilles heel” of the economy by some commentators. Total debt among China’s local governments may have reached 19.9 trillion yuan (3.3 trillion US dollars) by the end of 2012. This figure was reported in today’s edition of the Global Times, a government mouthpiece, citing a report from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, a key government think tank, which said the debt has reached an “alarming level” and poses a significant risk to the wider economy. This compares with total local government debt of 10.7 trillion yuan (1.7 trillion US dollars) reported in the last published official audit in late 2010.

Local government debt has spun out of control in the past five years amid an unprecedented building spree, in which cities, towns and provinces have strained to outpace each other and defy central government attempts to rein in overcapacity and wasteful investments. The local government debt problem is closely linked to the explosive growth of the shadow banking sector, which for the first time accounted for over half of all new lending in 2013. At the government’s December economic summit (Central Economic Work Conference) in Beijing, there was evident concern over local government debt. The official statement released from the meeting mentioned “controlling and defusing” local government debt risks as “an important economic task.”

Warning from Detroit

The regime’s nervousness is shown by the fact that a national audit of local government debt, the first since 2010, has still not been published. The audit was ordered by Premier Li Keqiang in June this year, following the declaration of bankruptcy by the US city of Detroit. At the time it was reported that at least 36 major Chinese cities had a greater debt-to-GDP ratio than Detroit. This list includes Nanjing, Chengdu, Guangzhou, Hefei, Changsha, Wuhan, Harbin, Xi’an and Lanzhou, according to business magazine Caixin. The similarities between Detroit as a former manufacturing stronghold and many indebted Chinese cities is also worrying.

Jiangsu province, for example, which is the second largest provincial economy in China, with a GDP greater than Turkey’s and Saudi Arabia’s, is experiencing major financial stress among local government finance vehicles (LGFVs) that were set up to channel cheap bank loans into mega infrastructure projects as part of China’s 2009 stimulus package. Indicating the problems across China, many of Jiangsu’s flagship companies – in relatively new sectors such as shipbuilding and solar power – are on the brink of bankruptcy, with no markets, slashing tens of thousands of jobs. If China as a whole is not yet a Japanese-style ‘zombie economy’ of loss-making companies that are kept afloat by debt rollovers and which act as a permanent drag on economic activity, this scenario has already arrived in provinces like Jiangsu.

Financially stressed local governments face even tougher times ahead as Beijing’s promised ‘reforms’ push up interest rates (to price capital more ‘efficiently’ and induce ‘deleveraging’), while also cutting income from land sales (to reduce rural unrest and wasteful construction projects). “With the slowdown of the economy and reduction of revenue sources, some local governments, especially those who heavily rely on resource development and land sales, will face greater pressure to pay back their debt,” said Zhang Yongjun, of the China Centre for International Economic Exchanges, quoted in the Global Times.

The latest local government audit was completed in October in time for the CCP’s historic ‘Third Plenum’ meeting in November. This meeting unveiled a further salvo of pro-capitalist economic reforms while the door was again slammed shut to any loosening of repression and political control. The fact that the audit has to date not been published suggests its findings are unpleasant, and the regime perhaps fears that revealing the true scale of the local government debt crisis could trigger further financial instability.

Shadow banking monster

The figure of 19.9 trillion yuan in combined local government debt, cited in the report from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), is from a separate survey conducted one year ago. Given the explosive growth of shadow financing in the past 12 months, this would suggest that the true level of local government debt is now significantly higher than 20 trillion yuan. Some estimates put it at 50 trillion yuan, which is equivalent to 90 percent of GDP. According to the CASS report, around two-thirds of the local government debt was owed to shadow banking entities at the end of 2012. This shows how indebted local government investment platforms are being forced to tap informal sources of new credit – at much higher rates of interest – in order to ‘rollover’ old loans. By doing so, they circumvent Beijing’s attempts to curb the growing debt problem and growth of the uncontrollable shadow banking monster, a potential source of financial turmoil as shown by the US financial meltdown in 2008.

China is trapped in a vicious circle whereby an ever larger share of new credit is used to service existing debts rather than fund new investment. The latest China Beige Book (CBB), a quarterly business survey produced by US economists based on interviews with Chinese companies, confirms this. It shows that the number of firms receiving new credit declined for the seventh consecutive quarter. “In the fourth quarter [of 2013], we’re seeing corporate loans decline significantly, very shockingly most of our bankers say less than 20 percent of their lending goes to new loans. Most of it’s going to debt rollovers or increases, they are not funding expansion. That indicates that this is not a period of strong expansion,” Leland Miller, president at CBB said.

So, paradoxically, while China is experiencing runaway credit growth it is facing a credit squeeze at the same time, constraining growth in all sectors except manufacturing according to CBB.

The government’s apparent refusal to publish its latest local government audit has also drawn criticism even in the state-controlled media. “The fundamental problem of local governments is that information about local debt is opaque,” Zhang Bin, director of the taxation office at the National Academy of Economic Strategy, told the Global Times. The pressure to suppress bad news is constant. Jamil Anderlini of the Financial Times reported, “Chinese censors have warned financial reporters not to ‘hype’ the story of problems in the interbank market, and in some cases have forbidden them from using the Chinese words for ‘cash crunch’ in their stories.”

An independent report from Haitong Securities estimates the total size of China’s local debt problem at between 20 and 30 trillion yuan, equivalent to 40-60 percent of GDP. Adding central government debt, unfunded pension liabilities and debts of the major state-owned enterprises, this would lift China’s overall public debt level to around 100 percent of GDP, higher than Britain or Spain.

Total credit in China is now equivalent to 210 percent of GDP, up from 125 percent five years ago. Not even Japan or the US experienced such a rapid build-up of debt in their pre-crash periods. “What bothers me is not the current level of debt but the pace of the increase,” Shen Minggao of Citigroup Global Markets told The New York Times. “But if the pace of growth is slowed or capped, that will have a direct impact on infrastructure growth.”

What is of further concern is that 2014 could be a crunch year for many of China’s local governments, with a large proportion of the debt falling due. This will increase the pressure to tap unofficial sources of credit from the shadow banking sector, engaging in a game of cat-and-mouse with Beijing, which is simultaneously trying to rein in shadow banking to avert a potential meltdown with catastrophic economy-wide effects.

The dilemma of ‘reform’

The problems facing Li Keqiang, whose ‘Likonomics’ doctrine promises “no more stimulus” and tighter monetary conditions, are shown by the end-of-year liquidity crunch in China’s money markets. This threatened a repeat of June’s liquidity crisis, which set off jitters on global financial markets. China’s interbank lending rates soared to almost 10 percent in the days before Christmas, close to the all-time high of 11.6 percent reached in mid-June, as major banks hoarded cash – fearing potential defaults by counterparts – while shadow finance entities scrambled for short-term funding to repair end-of-year balance sheets. “The fragile nature of [China’s] financial system remains a challenge for the central bank and poses a threat to the economy,” said Nomura’s China economist Zhiwei Zhang.

This second ‘cash crunch’ of 2013 suggests significant sections of China’s financial system, especially shadow entities like trusts and underwriters of wealth management products, are overextended and depend on short-term financing from the money markets to stay afloat. This replicates the dangerous pattern seen at Northern Rock in Britain, Lehman Bros, and the Icelandic bank system, pre-2008.

One of the biggest risks is with wealth management products (WMPs), which Fitch Ratings describes as a “hidden second balance sheet” of the banks. These opaque and sometimes fraudulent financial instruments alone are now worth an estimated US$2 trillion – equivalent to 54 percent of China’s famed pile of foreign exchange reserves. As Ambrose Evans-Pritchard of the Telegraph notes, “Half of all [WMP] liabilities have to be rolled over every three months and a further 25 percent every six months. There are reports that some are already under water.” Not for nothing has Xiao Gang of China’s banking watchdog CBRC described wealth management products as a “Ponzi scheme”. Yet their usage is growing!

The immediate liquidity crisis seems to have receded, with interbank landing rates falling back on 24 December, but this only came about after an effective u-turn by the People’s Bank of China (PBOC). Early on 24 December, in a well publicised move before the stock and money markets opened, it injected funds through ‘open market operations’, something it had refused to do for the previous three weeks as it attempted to crackdown on runaway shadow bank lending. The PBOC’s retreat repeats a similar turn of events in June. In a sense what we have witnessed is the market playing a “decisive role” and forcing the government to step back, but not in the way the CCP hoped when it wrote this phrase into its ‘Third Plenum’ resolution. The dilemma for the central bank, for Premier Li and the government’s recently announced reforms, is that the ‘painful’ measures they insist are necessary to achieve ‘sustainable growth’ and avert a banking crisis, could be the trigger for such a crisis.