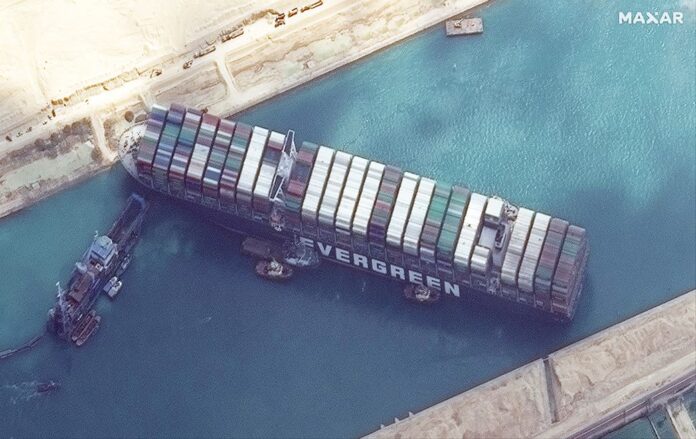

Memes and jokes have dominated social media using the image of the ship and the tiny digger — a metaphor for capitalism, lacking any genuine solutions to the ever widening range of crises it has created.

Anne Engelhardt, Sozialistische Alternative (ISA Germany)

Until last Monday (29.03) the Ever Given, one of the biggest global container ships in the world, blocked the Suez Canal. Having navigated into a sand storm, it turned sideways and got stuck in the shallow waters of the canal’s east bank, causing a massive disruption of global capital circulation.

Memes and jokes have dominated social media using the image of the ship and the tiny digger — a metaphor for capitalism, lacking any genuine solutions to the ever widening range of crises it has created. While the corporate media has bemoaned the disruption to global trade, hardly any attention has been paid to the severe impact on the hundreds of seafarers stuck on the Ever Given and 450 other container ships and maritime vessels affected by the blockade. The episode, which left thousands stranded for more than six days, has shone a light on the staggering exploitation and inefficiency of global supply chains, a historical flashpoint for both imperialist conflict and workers’ struggle dating back centuries.

The Canal

The Suez Canal represents one in three major maritime pathways for global trade, accounting for 12% of freight transport. Today, it is one of the 14 most sensitive choke points for food security, meaning its blocking can endanger food supplies in many regions, including to the point of famine in already poor countries. While blockades of this kind have happened before (in the past ten years alone, 25 ships were temporarily stuck in the canal), none of them has lasted six entire days.

The Suez Canal connects the Mediterranean Sea with the Indian Ocean and thus represents one of the shortest pathways between Europe and Asia. As far back as ancient times, the passage, which linked the Asian-European continent with Africa, was regularly flooded and used as a water road. Several attempts to construct the canal in 700 B.C. by Egyptian and later Persian emperors, led to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of workers. The Arab and Ottoman empires maintained control of the passage, while Spanish and Portuguese and later Dutch and British fleets had to surround the Cape of Good Hope to access Asian markets.

In the middle of the 19th century, the French and British colonialist empires finished the canal. Its construction forced about one million Egyptian peasants into slave-like labour, some ten thousand of whom died of work related accidents and from diseases such as cholera. The canal was finally inaugurated in 1869, utilized predominantly for easier (military and economic) access to the African and Asian colonies. Karl Marx writes in the first volume of Capital that the Suez Canal would allow the European capitalists to fully access the East Asian and Australian markets by the steam ship. The circulation of capital, which before the opening of the canal and the invention of the steam ship took twelve months, “has now been reduced to about the same number of weeks.”

In the context of the anti-colonial struggles that took place throughout Africa and the rest of the world, the canal was nationalised by Egypt in 1956, provoking military interventions from France, Britain and Israel. Eight years later, in the 1967 War, the canal was blocked once again for several months. Both military incidents caused insecurities for global shipping companies, which had just recovered and massively increased revenues after the end of World War II.

However, it was not only military conflicts that caused blockades of the canal; but also labour struggles, in which activists used the choke point as a means to fight against the corrupt Egyptian regime. Ten years ago, during the Arab Spring in February 2011, about six thousand workers organised a strike in Port Said and Ismailia, the cities along the Suez canal. Moreover, as the author Deb Cowen writes in her book The Deadly Life of Logistics: “Dock workers stopped work at the key port of Ain Al Sokhna, disrupting Egypt’s vital sea links to the Far East […]. Needless to say, this became a definitive action in the mass mobilization for regime change.“

The Ship

The container ship Ever Given is 400 metres long and able to carry about 224,000 tons of goods. Ironically, as Laleh Khalili writes in the Washington Post, container ships of this size were constructed and used by the global shipping industry in order to be able to avoid the Suez Canal. Because of the closures of the canal in the 1950s and during the war in 1967, shipping companies were forced to round the Cape of Good Hope. With the oil crisis in 1973 triggering a price shock, the speed of ships had to be reduced as a certain velocity consumed too much fuel. Hence, shipping companies invested in the expansion of the size of ships to transport larger volumes of cargo. As a result, so-called “very large crude carriers (VLCCs)” and “ultra-large crude carriers (ULCCs)” dominate the oceans and have forced ports globally to expand their berthing spaces or move away from port cities to enlarge their capacities. This led to a new economy of scale and a massive increase of containerized cargo.

Although these ships have been built to transport cargo and breakbulk a slower but larger extent, speed is an important cost factor in the global economy. This is why large ships like the Ever Given take the Suez Canal as a shortcut to lower transport costs (in this case from China to the Netherlands). Regardless of the ship’s size and the constant risk of getting stuck they continue to use it. In the past decade, China and East Asia have become the powerhouse of the global economy, with a container throughput (a measure of container handling activity) of more than 60%, ranking first place, well above Europe at 15%. Therefore, the connection between the two economic areas has been revitalised. The current economic crisis and the partial interruption of global trade circulation due to the pandemic caused a global imbalance in the spread of containers who are mostly stuck in China. This had already led to a shortage in transport capacities in which other parts of the world economy were affected. Bearing this in mind it is likely that the Ever Given, like other container ships, might have been “overloaded” and thus been too heavy to properly navigate through the canal.

The Ever Given did not only blockade other container ships (causing turmoil in the European just-in-time production) but also approximately 20 crude oil carriers, leading to a temporary jump in oil prices. The Suez Canal Authority (SCA) and the Egyptian state, who charge each ship between 250,000 and 500,000 dollars to cross the canal, lost these revenues as well as the fees that would have been obtained from the ships which decided to change route to avoid the traffic jam.

On top of the Egyptian state, insurance companies were also alerted by the incident. Insurers will be charged for the loss of revenues, for instance from the SCA but also other companies who deal with time sensitive goods such as perishables and components for just-in-time production, which are still predominantly produced in Asia.

The Crew

The blockade did not only interrupt global trade. It also disrupted the lives of hundreds of seafarers who were (again) stuck on board. The whole incident shows once again how little shipping monopolists are regulated, especially in terms of labour conditions.

The Ever Given, just like the large majority of maritime ships, runs under a Flag of Convenience (FOC) and is operating under a complex global ownership system. It belongs to a Japanese enterprise, but is chartered by the Taiwan-based shipping company Evergreen Maritime. A Dubai-based firm operated the loading and unloading in the various ports at which the ship berths. And the ship itself uses the flag of Panama, which allows the owners to avoid taxes and to pay low wages and secure low labour standards.

Globally, the maritime crews on container and breakbulk ships are separated in two groups. The officers are predominantly recruited from the East and Central European states like Ukraine and Russia and their maximum income is 3,000 dollars a month. The second group are the seafarers who are in the majority coming from the global South: nearly 15% come from China, 13% from the Philippines and another huge share comes from Indonesia, India and Malaysia. The seafarers work between ten and twelve hours on the ship, seven days a week with a monthly income between 700 and max. 1,400 dollars. At the time of the blockade, the Ever Given had a crew of 25 Indian workers on board. These are now facing arrest by Egyptian officials as scapegoats for the blockade, even though two pilots of the Suez Canal Port authority were also on board. Generally, the exploitation of the workers from the Global South is expanded to an extreme: While workers sign contracts of the length of already 11 months, their shifts are frequently expanded to fourteen or more months. The International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF) often has to force the shipping agencies to pay the overtime. Each year, between 30 and 50 million dollars of stolen wages have to be given back to the workers.

There are also reports of cargo ships that have been abandoned by bankrupt shipowners at ports, including their unpaid crew. In 2016, the South Korean Shipping company Hanjin abandoned its 50 container ships around the world with an estimated commodity value of 14 billion dollars, leaving crews without water and food, while local port authorities denied them access to land in order to fly home. All over the world, there are several neglected ships with crews, unable to depart from this floating prison. The worst consequence of such abandonment has been the neglect of a ship in the port of Beirut in 2013 with 2,750 tonnes of ammonium nitrate on board. The crew was only allowed to leave the vessel and receive visas to fly home after months of negotiation processes. The cargo of the explosive ammonium nitrate was, however, stored in a neglected warehouse close to the port and given up by the original customer in Mozambique. In 2020, when a nearby fire broke out the material detonated, causing a death toll of more than 200 people and a destruction of the port and parts of the inner city of Beirut.

In the same year, COVID-19 led to the so-called “Crew Change Crisis” which has forced about 400,000 seafarers to stay on board, while the same number was stuck at home and not able to start their shift. As borders have been closed, seafarers were denied visas or were stuck in the cities with no flights home. About 58,000 cargo vessels were affected by the crisis. Even today, the situation has not been solved. At normal times, 100,000 seafarers change shifts each month, globally. This number has been dramatically reduced. Between 150,000 and 250,000 seafarers were trapped at sea for up to 18 months. There is a lack of food and clean water, conditions have an impact on their mental health and there have been numerous reports of suicide.

As a consequence of this, many reports and articles have been warning of possible accidents — ships crashing into ports — or getting stuck at sensitive pathways. It is not clear, (but likely) if parts of the crew of the Ever Given itself had been affected by the Crew Change Crisis and its physical and mental impact. It is, however, close to a miracle that so far, from the background of the maritime human crisis, no worse accidents have happened, yet.

And the crisis is not yet over. Since the majority of the approximately 1.7 million seafarers are from the Global South, where vaccines might not be available for all until 2024, crews might carry the virus along the global value chain and endanger dockers and other transport workers. As long as the patents are not released from private property, the human maritime crisis will be prolonged. Additionally, the Suez Canal blockade might have also delayed the transport of vaccines from India, one of the major pharmaceutical producers in the world.

Capitalism is based on the physical and mental exploitation of workers and nature, the crisis at the Suez Canal has once again put on full display both its deepening contradictions and fragility.