ISA International Committee Statement

Introduction — “The Single Most Important Element of World Relations”

ISA has identified a New Cold War between US and Chinese imperialism, which has asserted itself, as “the single most important element of world relations” (ISA World Congress, February 2023). The war in Ukraine, increased military tensions and the arms race, the world economy and trade, power struggles over influence and resources, political crises — all are now interwoven with the imperialist Cold War. Of course, in the last instance, it is the living struggle of class forces that will decide the outcome of this complex process.

Summer and early autumn 2023 have seen new developments. In the Ukraine war, the continuation of a military stalemate, with a “war of attrition” along a 1,200km frontline running through Ukraine and the Russian-occupied territories has resulted in new crises for both sides, and more so for Moscow. The Wagner-led mutiny in Russia was the sharpest expression of the destabilisation of the Putin regime, and in Ukraine the dismissal of the Minister of Defense and all of his 6 deputies, amid corruption scandals, a lack of strategic gains with the counter-offensive in the front and recruitment difficulties.

The “Japanification” — deflation, stagnation and debt crisis — of the Chinese economy marks the end of China’s era of rapid economic growth. In the late eighties, aided by the collapse of Stalinism, global capitalism managed to prevent the 1987 financial meltdown from spilling over into the real economy. Today however, it is difficult to see how the adverse effects of the “Japanification” of the Chinese economy would not drag the global economy down, especially if China were to face its own version of the 2008 financial crisis. It is also hard to imagine how a boiling over of the mass anger and frustration stemming from economic burdens and uncertainty could be avoided. Elsewhere in the world, both the inflation/cost of living crisis, and the attempts to provoke recession to counter it, simultaneously feed anger and frustration. Notwithstanding the existing confusion, this will also result in concrete action by the working class and oppressed.

The BRICS summit in South Africa is portrayed in some quarters as a success for China and Russia, with the group admitting six new member states, but many observers have correctly stressed the national rivalries and tensions within this grouping. BRICS is torn between those aiming for it to become an anti-Western imperialism bloc, those who want to balance between the two blocs, and those who in general lean more towards the US-led bloc. Notwithstanding these factors, which will tend to take more importance as the contradictions between the two dominant blocs deepen, the effective expansion of BRICS does represent a relative boost for China and a warning for Western imperialism. This was also expressed at the recent G20 summit, where the final statement was described by some commentators as a victory for China and Russia, and an evident retreat from last year’s western-dictated declaration, particularly in relation to the war in Ukraine.

Extreme weather caused by climate change has also reached new extremes, with July 2023 the warmest month since industrialisation. Niger and Gabon became the fourth and fifth countries in Western and Central Africa since 2019 where military coups have taken place, and more could follow suit. New military rulers use mass anger against French imperialism to derive political capital for themselves, with other powers, especially Russia (often via Wagner involvement) exploiting this to advance their influence and access to resources. Africa is one the most important battlegrounds for the Cold War, with US imperialism attempting to counter China’s influence and power.

On the margins of this major confrontation, various additional “subplots” of inter-imperialist tensions also emerge, including between powers nominally on the “same side” of the Cold War — like between the Saudi and Emirati regimes in the raging war in Sudan, or among Western powers as shown by their differing approach to the new military regime in Niamey, and the one day war in Nagorno-Karabakh. In this era of capitalist disorder and crisis, the actions of local rulers in maneuvering or side-switching between the imperialist blocs has clear limits in terms of alleviating the misery of the masses or securing any significant regime stability.

The limits of non-regional powers attempting to maneuver between world imperialist blocs were demonstrated by the desperate position of the Pashinyan government in Armenia in the face of Azerbaijan’s move to ‘finalize’ its control of Nagorno-Karabakh in continuation of the 2020 war. Pashinyan failed to secure support from Russia or the West after hoping to gain some leverage by limited dealings with both of the camps — including by not supporting Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, but at the same time refusing to join the sanctions against Russia. Armenian exports to Russia soared 3-fold this year. Pashinyan’s wife’s visit to Ukraine, with a promise to provide humanitarian aid, and even the recent small joint military drill by Armenian and US soldiers near Yerevan (on 20 September) did not come close to counterbalancing the growing ties between Western imperialism and Azerbaijan, also due to its search for alternative sources to Russia’s oil and gas.

At the same time, the Kremlin, which sent peacekeeping troops to Nagorno-Karabakh after the 2020 war, cynically reacted through one of its spokespersons, Simonyan, editor of RT: “Pashinyan is demanding Russian peacekeepers to defend Karabakh. What about NATO?” (20 September). This looked like an attempt to charge a price from Pashinyan for his actions, and at the same time cover up for the weakening of Russian imperialism in the region and its inability to act in parallel with the war in Ukraine. The Aliyev regime in Azerbaijan enjoyed not only Russia’s “neutrality” and the EU’s complicity, but also strong backing by Turkey and modern weapons provided by Israel — “Azeri flights to an Israeli airbase spiked in the run-up to a military campaign launched by Azerbaijan in the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh” (Middle East Eye, 19 September). The logic of the massive arming camping of the recent years was commented upon openly in the Israeli press in the aftermath of the recent fighting: “The photos published on social media revealed the weaponry of each of the two sides: behind the arming of the Armenian army stand Iran and Russia, behind Azerbaijan stands Israel. Although this campaign is taking place 3,000 kilometers from here [Israel], it is a testing ground for Israeli technology — Iranian weapons against Israeli weapons on the battlefield” (N12, 21 September).

How will these developments and processes affect the Cold War and how will the Cold War’s twists and turns affect them? ISA’s constant updating of our analyses and perspectives are unique and the key to our activities and program.

The basis for our analysis of the Cold War is an understanding of imperialism. Lenin described how “an essential feature of imperialism is the rivalry between several great powers in the striving for hegemony”. The struggle for territory, resources and power leads to conflicts and wars. This is an objective process, not a result of decisions by individual politicians. This is clearly proven by Biden deepening Trump’s sanctions and policies against China and Kishida — a former “China dove” — deepening Japan’s turn back to militarism. In short, recent developments confirm our analyses of the Cold War as the main axis for world relations, rather than give cause to revise or downgrade its importance in our perspectives.

We have explained the New Cold War as a long term conflict between the two main imperialist states, both of which are shaken by multiple crises. The rivalry has an increasingly military character with the Ukraine war as a proxy war with enormous human costs, alongside increased tensions over Taiwan.

While Russian Defense Minister Shoigu says that “the collective West is waging a proxy war against Russia” (9 Aug), this is conscious one-sided cynical propaganda by the Putin regime to whip up support by portraying the Russian offensive on Ukraine as a defense against imperialist aggression. The Russian imperialist invasion, preceded by propaganda against the right of Ukraine to exist — with Putin denouncing Lenin and the Bolsheviks for their support of Ukraine’s right to self determination — was aimed in the first place at curbing Western imperialist interests in the region, as the Ukrainian state has been shifting away from Moscow’s grip. Western imperialism has seized upon the entangled invasion to integrate and co-opt the capitalist Ukrainian state under Zelensky into its sphere and, to strike blows against Russian imperialism, and through this undermine Chinese imperialism.

Our perspectives point towards the Cold War being an ongoing and sharpening, though of course not a linear, feature of world relations. Even if China’s economic momentum is cut across by a deep economic crisis and “Japanification” the outcome will not be like Japan’s “stalling” in the 1990s, after which Japanese imperialism accepted that it would not catch up with the US.

At this stage, the Chinese regime lacks confidence in its ability to win a war against the US and Western imperialism. The poor performance of the Russian army in Ukraine has certainly added to that, and a deeper economic crisis would further postpone China’s capacity to catch up. However, a regime in crisis could also engage in what they might view as limited adventures, but which have inherent potential to spiral out of control. In that sense, a deeper crisis in China can make the overall situation more dangerous.

New events and crises will have an effect on the exact tempo of developments, while the fundamental processes continue, short of the overthrow of capitalism and imperialism itself. The purpose of this short resolution is to update our perspectives and clear up some questions about the New Cold War, with the aim of leading to greater clarity regarding this crucial question.

Cold War Entrenched and Turbocharged

“The US and China remain on a collision course. The new cold war between them may eventually turn hot over the issue of Taiwan”, economist Nouriel Roubini wrote in late August. While giving his advice for how a war could be avoided, assuming a basis for “new understanding on the issues driving their current confrontation”, he warned of a sharp military conflict (28 Aug). Three months earlier, former US Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, warned that the rapid progress of AI, in particular, leaves only five-to-ten years to find a way to avoid war (17 May). He tempers this point by referring to domestic setbacks for China that could result from a war and “upheaval at home” as the Chinese regime’s “greatest fear” — as well as to “mutually assured destruction”. On his recent visit to China to meet China’s Defense Minister Li Shangfu, Kissinger, with his hollow diplomatic phraseology, nevertheless implied risks from the point of view of US imperialism: “History and practice have continually proved that neither the United States nor China can afford to treat the other as an adversary” (18 July).

We have explained that a war over Taiwan is not an immediate probability, but also warned that such a catastrophic outcome cannot be excluded in future based on the continuation of capitalism. Taiwan is ultimately a make-or-break issue in deciding which imperialist power will dominate the Asia-Pacific region: they can live with the current decades-long standoff, which is under increasing threat from both sides, but they cannot accept the victory of the “other side”.

Preventing the “separation” of Taiwan is fundamental for the CCP dictatorship and Chinese capitalism — not merely for ideological considerations and prestige, but ultimately because Taiwan’s re-accelerated centrifugal tendencies since 2016 pose a danger in themselves to stability on the mainland, potentially fanning domestic fragmentation and challenges to the CCP’s diktats. And US imperialism, for which Taiwan is a crucial geostrategic stronghold, under Biden has — with promises of defence, increased arms sales and visits by leading politicians in both directions — shifted away from the decades-long policy of “strategic ambiguity”.

The Ukraine war has shown that US imperialism will not stand aside when they see their core interests as being at stake. The war is, however, also a warning to Beijing on what to expect in a military conflict.

While not concluding that another major war is close, ISA recognises the military build-up taking place and the dangers. Events since we first elaborated the concept have seen the Cold War further entrenched and turbocharged.

The key conflict over restrictions on technology, Artificial Intelligence and rare earth metals has a strong military element. All modern weapons — fighter jets, missile guidance, electric vehicles — rely on rare earth metal components of which about 70% are currently mined in China, also home to at least 85% of global processing capacity. Washington has pressured its allies — most importantly the Netherlands, with the monopoly company for advanced chips-producing machinery (ASML) — to follow its lead on restrictions on microchip technology exports to China. For ASML this bitter pill was made more palatable with promises of multiple new microchip factories being built in the US, Germany and Eastern Europe, all backed by generous state subsidies. Massive investments in chip manufacturing by several countries when demand is already slowing could add another destabilizing factor to the world economy.

In one of the latest measures taken by Biden in early August, blocking certain tech investments in China, the US president declared a national emergency to stop business deals “in sensitive technologies and products critical to the military, intelligence, surveillance or cyber-enabled capabilities.” Production projections for semiconductors and microchips in China have been drastically revised down.

Already Biden’s Chips & Science Act and Inflation Reduction Act were declarations of economic war, with $400 billion in subsidies mainly for semiconductors and microchips. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company’s projected factory in Arizona worth $40 billion is one of the biggest ever factory investments in the history of capitalism.

China has retaliated with restrictions on imports and exports, but the relationship is asymmetrical and China risks further damaging its economy if it matches every US attack tit-for-tat. In May, the CCP dictatorship, citing national security, banned products from US company Micron, who in 2022 had sales in China worth $3.2bn. In early August, export controls were introduced on “niche metals” gallium and germanium, of which China produces 80% and 60% of the world total respectively. Both are used in military equipment.

Decoupling continues dramatically and sharply, although it remains a risky and complex process for capitalism. The US ruling class has been debating how far it might risk to go, fearing a backlash. Thus the White House advocates a highly selective ‘technological Iron Curtain’, with its ‘small yard, high fence’ strategy, focusing currently on attempting to wall off the most advanced tech from China. Nevertheless, Chinese exports to the US fell by 12 percent in 2022. The Economist describes how: “In 2018 two-thirds of American imports from a group of ‘low-cost’ Asian countries came from China; last year just over half did. Instead, America has turned towards India, Mexico and South-East Asia. Investment flows are adjusting, too. In 2016 Chinese firms invested a staggering $48bn in America; six years on, the figure had shrunk to a mere $3.1bn. For the first time in a quarter of a century, China is no longer one of the top three investment destinations for most members of the American Chamber of Commerce in China.” (‘Joe Biden’s China strategy is not working’, 10 August)

The US-led and Chinese-led camps have been further consolidated by events. For the respective imperialist camps, national security, militarism and the strengthening of the state have asserted themselves more forcefully as compared to short term profits and trade. National capitalist classes in second-tier imperialist states such as Germany have accepted a high economic price in order to stand firmly with western/US imperialism in the Cold War — a cost that they will attempt to force on to the working class through increased exploitation and austerity. They have no choice, such is the brutal logic of imperialism.

US imperialism’s leadership in Nato and the G7 has been significantly strengthened by the Ukraine war. While not having exactly the same interests, French and German imperialism, rather than acting more independently, have largely fallen into line. US-led security pacts, AUKUS, Quad, almost constant military exercises in East Asia and an Asian turn by Nato, inviting Japan, South Korea and Australia to its summits, underlines the consolidation of the US bloc.

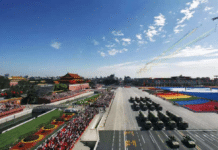

China’s bloc is much smaller, with Russia as its only major reliable, though destabilized, junior partner. Since the start of the century and especially under Xi Jinping, the Russian army and the Chinese PLA have participated in each other’s exercises and held more frequent and bigger exercises — more than six such exercises since the Ukraine war started.

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, China’s exports to Russia have increased sharply (by 67% in the first half of 2023) and are close to half of Russia’s imports. Despite the failure of Putin’s war aims and the crisis of his regime, Beijing has no alternative but to maintain the alliance. The CCP’s bottom line is to prevent the coming to power of an anti-China regime in Russia, which would seriously undermine its strategic position vis-a-vis US imperialism. While China’s regime has “tactical” differences with Putin on certain issues, its overall geopolitical interests would suffer a huge blow if the alliance was to break down.

China’s main answer to the alliances of US imperialism is its economic strength and trade. In the Global South — Latin America, Africa and South East Asia — China is the largest trading partner and lender. A “pivot to the south” has occurred: For the first time, in the first part of this year, China exported more to the countries in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), than to the US, EU and Japan combined. At its summit in Hiroshima in May, the G7 major western imperialist states, recognising China’s lead in this regard, made a statement against Chinese economic coercion and invited several non-G7 states including Brazil, India, Indonesia and Vietnam.

Using trade, China is backing regimes such as the dictatorship in Iran which is in conflict with US imperialism. China also has increased its business with Saudi Arabia, a traditional US ally. Beijing wants to tap Saudi and Middle Eastern capital to help ease its burden in the BRI, where Chinese capital has now reached exhaustion point.

The Saudi regime, for its part, exploits the imperialist Cold War as much as it can to get the maximum benefits for itself from both sides, although it remains ultimately anchored in Washington’s camp. The monarchy, despite serving as the largest petrol station for Beijing, strives to squeeze a ‘mutual defense treaty’, out of the Biden administration along the lines of the US’s military relations with South Korea and Japan, as well as an agreement on domestic uranium enrichment to build up its regional deterrence. Given its fear of any relative shifting away from the region by US imperialism, and after a substantial part of its geostrategic ambitions over the last years have been frustrated, not least in Syria and Yemen, Bin Salman is more eager to secure a deal with Washington, despite the price tag of curbing technological ties with China. Biden’s determination to conquer this major deal, which aims to include a normalization of Saudi relations with Israeli capitalism (and oppression of the Palestinians), as part of a new “security architecture” in the region, comes alongside the declaration of a US quasi alternative to BRI via the ambitious India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC) — dubbed by Biden a “game-changing investment”.

This is an assertive response aimed to cut across the ascending role sought by Chinese imperialism at the expense of the relative waning of US imperialism’s grip over the region. Syrian dictator Assad, saved by Russian imperialism, met with Xi in Beijing (22 September) for the declaration of a ‘strategic partnership’, following his regime’s readmission to the Arab League under Saudi pressure in May, and the Chinese-brokered Saudi–Iranian détente in March. The latter was a more serious concern for Washington than the 2021 China–Iran agreement, as a more direct attempt to further consolidate relations with ‘pro-US’ regimes in the Gulf, which have so far also refused to toe Western imperialist line in the ‘technological war’ or in regard to sanctions over Russia. The fact that Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Egypt, along with Iran, are among the new BRICS members gives in itself another impetus for attempts at new US assertiveness in this arena.

However, US imperialism cannot restore its regional hegemony of two decades ago, and faces serious obstacles. The idea of a revival of the 2015 ‘nuclear deal’ with Iran seems off the table, despite the limited US–Iran prisoners deal (18 September) and attempts to reach ‘understandings’ over Iranian uranium enrichment. A military treaty with Riyadh may also face difficulties in US Congress and Saudi nuclear demands already raise objections from the Israeli regime.

Israeli–Saudi normalization — although the process is in an unprecedented phase — is undermined by a destabilized Israeli government that is most intransigent against any concessions to the Palestinians. Thus, the Saudi monarchy attempts to bribe the Palestinian Authority with hollow promises, as expressed by the Saudi ambassador to Jordan during a visit to the Israeli-occupied West Bank, who cynically claimed efforts “towards establishing a Palestinian state with East Jerusalem as its capital” (26 September). Above all, any long-term ambitions by the super-powers or regional powers are pursued on a shaky ground, against the backdrop of a highly destabilized region that has seen the most concentrated processes of revolution and counter-revolution over the last decade and a half — and these will remain a decisive factor

In Latin America, another important Cold War battleground, China’s role has been transformed in the last period. It is now the number 1 trading partner to South America as a whole, and has signed 20 countries in the region up to the BRI. It has also not held back from using its economic role to exact geopolitical leverage, for example five countries have severed diplomatic ties with Taiwan as a condition for growing ties to China. The decline of US imperialism — which remains a decisive influence in the region — has also been highlighted by its failure to convince any Latin American government (with the partial exception of Chile) to fully toe its line on the war in Ukraine.

The expansion of BRICS with five authoritarian regimes — Egypt, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Ethiopia, United Arab Emirates — plus Argentina is a reflection of a distrust of US imperialism and an eagerness to play a larger role in global economics and politics. In the UN, 32 governments abstained from voting against the Russian occupation on the anniversary of the invasion of Ukraine, on 24 February 2023. Among them, alongside China, were India, South Africa, Ethiopia, Algeria, Kazakhstan and Sri Lanka.

Within BRICS, China is the dominating power with a 19% share of global GDP, more than the other states, including the six new member states, combined. China has also been successful in expanding the role of its currency, the renminbi, through trade deals.

The expansion of BRICS, however, does not mean it’s a “Chinese bloc” or a converging geostrategic alliance. It is a loose economic bloc, with a limited geopolitical weight, as it doesn’t represent cohesive common interests. Economically, it gives a certain room for independence from Western imperialism, although US imperialism still has possibilities to put economic pressure on BRICS states. But Chinese imperialism in no way offers a way forward or better conditions for loans and debts. Pressure on states with debts to China, mainly within the BRI, will increase with China’s own economic crisis. This is a key example of why a BRICS currency is very far from becoming reality. Most optimistically, a BRICS “currency” would be no more than an accounting unit like the IMF’s “SDR” (special drawing rights) — an accounting measure but not a real currency, which would in practise be a proxy for the Chinese renminbi. With its “mishmash” (Roubini) of regimes and economies, BRICS is light years from the minimum level of cohesion and integration needed to launch a common currency. However, opportunities to trade in currencies other than the dollar will be made comparatively easier.

Militarily, and even in the domain of diplomacy, BRICS is also a long way from becoming a bloc as there are many tensions and contradictions between member states. In 2020–22, there were several military incidents between Indian and Chinese troops, with dozens of soldiers killed. Both armies continue a military build up on the border. In his visit to Washington in June 2023, with the focus on common actions against China, Indian PM Modi signed new defence and technology agreements with the US. India also opposes the BRI and aligns with the US-led bloc in trying to blunt the BRI. India has unquestionably taken significant strides recently in aligning itself with the US-led bloc and diversifying its sources of defense supplies away from Russia. In parallel, South Asian countries and the Indian Ocean region are becoming an intensifying arena of geostrategic rivalry between China and India, which is supported here by US imperialism. Nevertheless, the Modi government still maintains a limited degree of maneuvering between the blocs in order to leverage India’s increased geopolitical and economic value on the global stage.

Within the original BRICS countries, there is a certain tension between China and Russia on one hand, who want to see it develop as a clear counterweight to the West, and India and Brazil on the other, who seek to maintain their relations with the West. This was also shown in the BRICs expansion being more limited than Beijing had hoped for with nations like Belarus, Nicaragua and Cuba not granted admission for now. Of the six new BRICS member states, four (UAE, Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Argentina) voted in the UN for Russia to withdraw from Ukraine.

For China, despite its limitations and disunity, BRICS is a way of bringing those governments some distance away from the US. Noting these limitations, which will force China to lower its expectations, we can still expect BRICS will play a more prominent role in the coming period, portraying itself as a megaphone for the grievances of the so-called Global South. Biden’s notable shift in tone vis-à-vis the neo-colonial world during the last G20 summit (his support for taking the African Union into that group, his echoing of the need for reforming western financial institutions to assist the “Global South” etc) reflects the objective pressure from China’s diplomatic strategies on US imperialism and the intensified drive to woo those countries by each bloc.

Even with some powers trying to balance between the two Cold War blocs, and the existence of tensions within the blocs, these bloc formations are long-term, decisive and primary for world relations in the new era of disorder.

War in Ukraine

The war in Ukraine was both caused by the New Cold War and is, in itself, an event which turbocharged it. As we have explained in internal and public material, the war solidified the blocs on both sides of the conflict, dramatically accelerated economic decoupling, and drastically raised the stakes of the conflict on all levels.

The ISA International Committee statement approved in April 2022 correctly analyzed that, following the war’s outbreak, “The possibility of war between NATO and Russia is now greater than at any point in the Cold War between the U.S. and the Soviet Union” — because the intensifying inter-imperialist struggle in this era is no longer restrained by a conflict with Stalinism, and world relations have profoundly destabilized. Each one of the many steps which have escalated the war since then, as one “red line” after another has been swept away, have underlined this. These were certainly kept at bay to avoid direct military collision between Russia and NATO, or the spreading of the war beyond the borders of Ukraine. However, the vicious inner logic of the war demonstrated, with each “red line” crossed, the injection of further instability and uncertainty, increasing the potential risk of a greater conflagration.

This is one of the reasons that ISA’s understanding of the nature of the war in Ukraine — as fundamentally and primarily an inter-imperialist proxy war reflecting the sharpening global imperialist power struggle — is of such great importance. Our opposition to this war is rooted in our opposition to the world’s imperialists dragging the world into a spiral of bloody conflict, and in our socialist, anti imperialist programme as a whole, which stands, from the point of view of international working class struggle, irreconcilably opposed to imperialist invasions and in defense of equal national rights.

At the time of writing (September 2023), the war has been underway for over 18 months. Through several stages, including some dramatic twists and turns, the fighting has evolved into a bloody stalemate, with minimal changes to the anatomy of the front line over more than 6 months. Russian troops are still occupying roughly one fifth of post-1991 Ukrainian state controlled territory, and have built substantial defensive fortifications.

In September, Ukraine’s long-anticipated counter-offensive entered its fourth month. The Ukrainian army, with nine brigades equipped and trained by NATO, made some progress in the oblasts of Zaporizhia and Donetsk, but at least so far, had failed to achieve a strategic breakthrough. While under great pressure, Russian troops seem to avoid disintegrating. They were also able to create some pressure of their own with small advances in the Kharkiv region (Kupyansk).

There is an ongoing discussion in pro-Ukraine/NATO circles as to whether the offensive should be considered a failure. While it has certainly been a failure so far, we must remain open on how the fighting will evolve. A continued stalemate along current lines, but also deeper inroads into Russian-occupied territory before winter cannot be ruled out. It seems quite unlikely that this year’s Ukrainian offensive will achieve a strategic breakthrough to reach the Azov sea, cutting Russian supply lines to Crimea.

But it is crystal clear, and of enormous importance for the working class, that the war, including Russian attacks and the Ukrainian counter offensive has led to massive losses of human life on both sides. Tens of thousands of soldiers have been killed and maimed. Villages and cities are being turned into rubble by the fighting. Parts of the countryside will be a deadly trap for decades, full of mines and murderous cluster bombs used by both sides.

Despite the deepest crisis faced by the Putin regime in decades — culminating in the armed mutiny led by his now-deceased former person for special operations Prigozhin — Russian positions have largely held. With unsuccessful attempts to recruit more contractors and volunteers to make up for the losses, Putin would likely be considering a fresh round of mobilization, possibly to launch new offensives once Ukraine’s main push peters out. This will, of course, risk new episodes of internal crisis within Russia — at a particularly sensitive time for the Putin regime, with the upcoming presidential “election” in spring 2024. A new law passed this year to penalize anyone ignoring draft notices — including being banned from leaving the country, prohibited from driving, or getting a home or registering small businesses — shows that more repression would be needed to enable a second round of mobilization. The unpopularity of such a move is also indicated by state orders to the media not to cover any rumors of a new mobilization.

Stalemate on the battlefield has however, not prevented the forward march of the war machine on both sides thus far. Despite slow progress, Zelensky’s long-standing push for F-16s will eventually come good. Russia’s brutal missile and drone attacks on Ukrainian cities and civilian infrastructure, including schools, hospitals and energy networks continue to take a high toll in mainly civilian and often children’s lives. Ukraine has also dramatically escalated its campaign of attacks inside Russian territory and even more so in Crimea, where attacks were few and far between during the first year of the war. This is also aimed at attempting to force Russian troops to regroup, exposing weak points in the long frontline. For the most part however, US and Western officials have thus far resisted the idea of exporting the conflict inside Russia’s mainland, and have refrained from permitting the Ukrainian army to use Western-donated missiles for such a purpose, due to fears about the potential for a direct confrontation between NATO and Russian forces.

New Western weapons have also provided Kyiv with the tools for important escalations. While progress on the battlefield has been slow, Ukraine has made use of long range ‘Storm Shadow’ missiles from the UK and SCALPs from France to inflict meaningful blows to Russian supplies, equipment and logistics in the rear.

Another serious escalation has seen the Black Sea reopened as a battleground, in the context of the collapse of the “grain deal”, following Russia’s refusal to renew. Ships have to run the gauntlet through shipping lines, while Ukrainian ports have been mercilessly attacked by Russian missiles. Although Ukraine has attempted to export its produce on land-routes, several countries in the region, with the agreement of the EU, have banned the import of grain from Ukraine after widespread protests by farmers, which has seen serious tensions emerge, especially between Ukraine and Poland. The suspension of the deal has put also further pressure on China as it is the largest importer of Ukrainian grain. After Putin suspended the deal Zhang Jun, China’s permanent representative to the United Nations, called for the immediate resumption of Ukrainian agriculture exports, without placing any blame on Russia for the crisis.

New escalations could take many forms on both sides. Both direct NATO intervention and the use of nuclear weapons are currently highly unlikely, in no small measure because of the ferocious backlash this would generate among workers and young people on an international scale. However, there are many steps short of these outcomes which would have serious effects. These could include an escalating war in the skies, and the crossing of new “red lines” in international support for either side. This could include a change in posture by Chinese imperialism to more openly back Russia.

While voices pushing for escalation remain strong, including in several governments in Eastern Europe, in other quarters, appetites are waning for a drawn-out “forever war” of attrition. Public opinion in the US is turning away from sending further billions into a prolonged war, and the 2024 Presidential elections present a major dilemma for US imperialism and NATO, with a potentially existential question mark over continued US backing for the war, especially in the case of a Trump victory. Trump and the wing of the Republicans who pose as “antiwar” on Ukraine simply believe this is the “wrong war” and want an even more concentrated focus on China. The entire US political establishment is united in waging the New Cold War with China even though tactical differences in exist on how to achieve this.

Ukraine’s stalled counter-offensive, if no strategic military breakthrough is registered in the coming months, would further undermine enthusiasm among sections of its NATO backers, and feed tensions and contradictions within the Western bloc over how to proceed. A “blame game” is already developing. Zelenskyy said in a CNN interview that he didn’t get “all the weapons and material” on time “to start our counter-offensive earlier” (CNN 6 July). US officials briefed the New York Times that “only with a change of tactics and a dramatic move can the tempo of the counter-offensive change” and that “Ukrainians were too spread out and needed to consolidate their combat power in one place” (22 August). In this context, Stian Jenssen, director of NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg’s private office, said one solution to the ongoing war could be for Ukraine to offer Russia territorial concessions in return for NATO membership (15 August). British military analyst, Frank Ledwidge, advised Western imperialism, that “the west needs to unite around a workable, saleable long-term plan and an achievable end state. This need not be the same as Ukraine’s” (1 September).

While neither side seems to favour a truce or meaningful negotiations any time soon, pressure for such an outcome is undoubtedly increasing. However, even if such negotiations were to begin in earnest, navigating the “red lines” of either side in the context of escalated Cold War tensions would be extremely challenging. The Ukrainian regime would be under enormous internal pressure to refuse concessions of territory to Russia, and not rule out NATO membership. Putin in turn would not accept any outcome akin to defeat that excludes significant territorial gains and involves Ukrainian NATO admission, at least without much more significant problems on the battlefield. In fact, despite the multitude of failures and crises for the Putin regime, a perspective of a likely “Russian defeat” would be over-abstract. A return to pre-2014 and even pre-2022 borders is highly unlikely in the current balance of forces, unless in a context of a collapse of the Putin regime, and a mass upheaval. However, in a scenario of an enduring military stalemate after the coming winter, some form of a ceasefire with tactical concessions and partial agreements cannot be ruled out.

War weariness is also beginning to take a heavy toll within Ukraine itself. Given the important role that the superior motivation of Ukrainian forces has played thus far in the war, this is more than noteworthy. While the first phase of the war was symbolized by long queues at recruitment centers and burgeoning volunteer corps, reflecting a population which was highly motivated to fight, more recently the call from an army recruitment officer is met with more dread than elan, as Kyiv is forced to draw on an increasingly reluctant reservoir of people. Zelensky’s sacking of every regional head of military recruitment in the country in August in response to widespread corruption, illustrates how much of a concern this phenomenon is for the regime.

These firings were followed up by the dismissal of Ukrainian Defense Minister, Reznikov, and his deputies in September, amid another corruption scandal. This move implies growing nervousness in the Zelensky regime in the face of signs of a relative waning momentum of its war campaign, and thus its strive for, as Zelensky puts it, “new approaches and other formats of interaction with both the military and society as a whole” (3 Sep). Reznikov was replaced by Rustem Umerov, a Muslim, from a Tatar minority family in Crimea, and a co-founder of the “Crimea Platform” (an international diplomatic summit initiated by Zelensky). He is considered to be a key negotiator who “was part of the delegation that negotiated with Russia prior to the conflict. He played a key role in the grain deal” (6 Sep), and was part of the Ukrainian delegation to the “peace summit” in Saudi Arabia in August and to the Arab League’s summit in May. His appointment, while doubling down on the Zelenskyy regime’s aspiration to re-establish Ukrainian state control over Crimea, and fitting in with its attempted appeals for support from the “Global South”, also implies taking into account potential options for negotiations.

Morale was low in the Russian army from the very beginning, with soldiers questioning the invasion itself, added to by the incompetence of the military leadership. After the start of “partial mobilization” one year ago (September 2022), under the pretext of a war against the “collective might of the West”, around 250,000 fled Russia to avoid being drafted. Some of those who were drafted took part in various types of protest against lack of food, basic gear and even weapons. Families of those at the front initiated protests in the rear. All this implies that the problem of morale has only been aggravated — something that was expressed, though in a twisted way, in the sympathy among some rank and file soldiers for the Wagner march on Moscow. Though many of the soldiers that initiated protests were imprisoned or simply sent as cannon fodder to the front line, the discontent is still there.

Further losses and failures will further decrease the Russian troops’ readiness and ability to fight, though Ukrainian attacks on Russian territory, especially with western weapons, can play into the hands of Putin and motivate a section of the troops. While the morale of Ukrainian soldiers is definitely higher, the meatgrinder of the front, failed or painfully slow offensives and the turning of whole regions into a new version of the WW1 fields of Flanders will lead to more questions amongst Ukrainian youth and workers as to whether the war can be won militarily or whether it is worth dying and killing for.

Russia and China

For Xi Jinping’s regime, the Cold War marks a new epoch. China is no longer a fast-growing “workshop of the world” in an era of capitalist globalisation. Instead, Beijing is confronted with an offensive led by US imperialism in all fields — the economy, technology, militarily. While pushing back against US imperialism, the Chinese regime also seeks to continue extending its global influence, including by posturing as a ‘peacemaker’, brokering the Saudi-Iran deal, and in relation to the war in Ukraine. It is doing so to further undermine US imperialism in the predominantly neo-colonial “Global South”. The Ukraine war has drastically increased the pace of Chinese businesses being pushed from Western markets. To this should be added the discontent with the regime shown in the historic but still limited protests triggered by zero covid last year and the threats to Chinese capitalism from record youth unemployment, stagnation and huge debts

The reply of the dictatorship is further increased repression at home, military build up, and to try to speed up the development of its own parallel technology. The already dominant nationalist propaganda has been stepped up further, alongside the cult of personality around Xi Jinping.

The relationship between China and Russia should be seen in this light. The Cold War — the concerted offensive from US imperialism — dominates. Beijing needs its alliance with Moscow. It provides a secure northern border, cooperation with a nuclear weapons state, a more secure source of oil and gas (that is not subject to possible blockade) and an allied regime that is a mortal enemy of US imperialism.

That is why Xi Jinping went on his only state visit so far in 2023 to meet Putin in Moscow. And then again in May met Russian Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin in Beijing. “China and Russia should find ways to ‘upgrade the level of economic, trade and investment cooperation’, Xi told Mishustin, with energy an area in which they could expand collaboration”, Reuters reported. A month later, Beijing, after some silence, reiterated its support for Putin’s handling of the Prigozhin mutiny.

The China-Russia bloc is not an alliance of equals. China’s economic advantage (more than eight times larger than Russia’s) has now been added to by the Russian weakness shown in the Ukraine war. Bilateral trade is increasing rapidly, by over 40% so far in 2023, with China exporting agricultural products and technology while importing more oil from Russia. For Russia, it is estimated that increased trade with China roughly compensated for lost trade with Germany and France.

At the same time as keeping its alliance, Beijing wants to present itself as not directly involved in the war, including to avoid sanctions similar to those applied against Russia. This is what’s behind the so-called “peace initiative” from Xi Jinping, and China’s attendance at the “peace summit” in Saudi Arabia. Xi’s “peace plan” includes traditional CCP-language such as “territorial integrity”, but does not criticise (or mention) the Russian invasion or demand withdrawal of its troops. As a tactical turn, but also to assist Chinese exports and grapple with problems at home, Xi Jinping, since the end of zero covid, has held back the “wolf warrior” diplomacy. This, however, did not lead to any reprimands against China’s ambassador to France Lu Shaye, when he stated that Ukraine, as a former part of the USSR, lacked national rights. There is a parallel here with Biden’s repeated statements that the US “will defend” Taiwan, followed by US officials walking this back.

Chinese media and social media — of course controlled by the CCP dictatorship — is completely dominated by Kremlin war propaganda. The invasion and war are described as a “conflict” that is caused by US and Western imperialism.

Military cooperation has been stepped up since the Ukraine war started. In July, a joint Russia-China exercise in the Sea of Japan for the first time involved both air and naval forces.

The Ukrainian government as well as the US have reported about Chinese components and ammunition used by the Russian army in Ukraine. Of course China wants to avoid being involved, but further steps are likely if Putin’s regime is faced with collapse, with the possibility of an anti-China government taking over or disintegration of the Russian Federation.

With a long “meat grinder” war, the costs on both sides can lead to negotiations, participated in by imperialism on both sides. This is not the most likely short term perspective, but could develop over time. As negotiations following stalemates in other wars have shown, they will not mean the end of the conflict. Some commentators have pointed to the Korean War which 70 years later officially still has not ended. The tense inter-Korea border may prove pale in comparison to a potential Russian-Ukrainian ceasefire line.

Xi Jinping’s bloc with Putin has not been fundamentally shaken despite the failures of the Russian army in Ukraine or by the general weakening of Russia. Economic crises are also most likely to bind the two states closer to each other. The CCP regime has no alternative partnership.

The rapid end of zero covid following the November protests shows the CPP dictatorship’s fear of movements from below, above all movements of workers. In Russia, Prigozhin’s mutiny in a distorted way reflected the massive discontent and crisis of Putin’s regime. Protests and movements will further increase the inner tensions in the regimes. It is revolutionary movements of the working class that can fundamentally shake imperialist regimes and their blocs.

Our Programme on the War

As explained in both the aforementioned IC statement and the resolution adopted by our World Congress in February 2023, inter-imperialist proxy war is the primary characteristic of the war in Ukraine, but it is not the war’s only feature. There are several other elements, including the national defense of Ukraine against Russia’s imperialist invasion and occupation, which is undoubtedly to the fore in the minds of the Ukrainian masses and among a mass of workers and youth in eastern and western European countries affected directly by the war.

ISA must ensure that our material and analysis takes all important elements into account, and be clear in our fulsome solidarity with the main victims of this bloody war: Ukrainian workers and youth. This solidarity is inclusive of their right to organize to defend their livelihoods and for self-defense against imperialist aggression. It is of utmost importance that in stressing our support, we do so based on class solidarity, stressing the need for class appeals to the mobilized Russian forces, a large proportion of whom are workers, as well as to the billions of working masses and poor across the world suffering from the consequences of the war.

However, this is fundamentally in contradistinction with any support to the military campaign of the NATO-backed capitalist Ukrainian state and their supply of weapons. We reject any slogans that amount to such a support and an echo to the Ukrainian bourgeois nationalist aspirations of pursuing the war until “victory” — which will be no victory for the working class at all.

The factor that is central to determining our programmatic approach is our characterisation of the war itself. All wars throughout the history of capitalism and imperialism have involved bloody brutality, invasions, suffering and heroism. Marxists approach wars concretely, based on analyzing the different factors at work in the process of development of the conflict and the roles of all different social groups therein. We develop a position with the aim of building solidarity and unity in struggle of the international working class.

In relation to historical comparisons with wars where national resistance to imperialism played a more primary role, our 2022 IC statement asserted, “This war comes in a thoroughly different context — one of an accelerating division of the world into two spheres. It is therefore in certain ways more akin to the wars of the early 20th century — an inter-imperialist conflict taking place between two competing capitalist blocs. Russia is ultimately, if on the surface initially somewhat tentatively, backed by China. The Zelensky government is conversely backed by Western imperialism.” In the same vein, our World Congress resolution stated, “a better historical comparison would be the Balkan Wars that occurred right before World War I and fed directly into it”.

This analysis has implications for our programmatic approach. Our international programme on the current war, arising from our characterisation of the same, correctly emphasizes our opposition to the Russian invasion and the war, and to the reactionary aims and interests of both imperialist camps. We call for a mass international working class movement to end the war, stop the bloodshed and prevent imperialism from unleashing new bloody conflagrations.

We mercilessly expose in our propaganda the ugly class interests behind all the imperialist forces and their allies in relation to the war, arguing that the war and occupation can only be ended through an independently organized and politically conscious struggle by the international working class, including in Ukraine, to overthrow their own capitalist and imperialist governments. We struggle to expose the false narrative of “freedom versus autocracy” pushed in Western countries to justify support for the war, and likewise the false idea, especially prominent in parts of the neocolonial world, that Russia and China represent progressive counterweights to US imperialism in the current epoch.

This clearly antiwar position is organically connected to our opposition to the Russian invasion of Ukraine and solidarity with the Ukrainian people. From the beginning of the war, we have supported the idea of independent working class resistance, including armed resistance, to the Russian invasion. This has included attempts to spell out aspects of what such independent resistance would look like in practice, and some necessary elements of its programme, which remains important and should be elaborated even further.

However, we have also made clear that this aspect of our programme has at the moment a necessarily somewhat abstract nature, due to the reality of the war and the class struggle. Our World Congress resolution acknowledged, “…also — and crucially — that at this stage the Ukrainian working class has no party, no independent voice or mass organizations, which hinders its ability to act independently from the capitalist Zelenksy regime and its Western imperialist backers. However, without in any way diminishing our overall focus on the war’s inter-imperialist character, it is appropriate and correct for us to reflect the objective need for such an independent working class struggle. Although it does not exist at this point, things can change given the tumultuous events that will take place in the months and years ahead.” This reality has been further cemented since then.

Of course Ukraine is still under martial law and all protests and strikes are forbidden. Under ‘the Organisation of Labour Relations During Martial Law’, collective agreements remain on paper but are not enforced legally, and bosses can suspend parts of collective agreements without consulting unions. A suspension of “payments for recreation” meant a suspension of payments to unions. The budget law prevents wage increases. The trade union bureaucracy in Ukraine, which in essence advocates national unity with Zelensky’s capitalist government, opposed those measures but didn’t organize struggle. Instead, they appealed to the UN and fellow trade union bureaucrats in Europe to lobby the Zelensky government to conduct a “social dialogue” in the face of a one-sided class war. Nevertheless, local protest did take place among mine workes and healthcare workers, along with petitions and online protests against gender-based violence, for same-sex marriage, and street protests in Kyiv against real estate sharks. One protest placard in Kyiv read, “What hasn’t been destroyed by the Russian rockets is being destroyed by our officials and builders” (9 September).

We should aim to build links with workers and youth in Ukraine, with the aim of building a revolutionary party. We should be confident that, despite powerful nationalist pressures, an echo can be found for our programme. This potential can grow, amid growing frustration with Zelensky and the army leadership — as successes on the front seem further and further away — and other signs of mounting anger against the government in some sectors, attested by nurses, doctors and care workers organizing against layoffs and unpaid wages.

We stand firmly opposed to imperialist annexations of any part of Ukraine, and squarely for the right of Ukraine to exist as a nation, free from all imperialist interference and subjugation. We oppose the manipulative and cynical usage by the Putin regime of the right of self determination as pretext for annexation. After the sham referendums last year on annexation, Putin stated that “Donetsk, Kherson, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia used their right to self-determination, enshrined by the UN”. We stand for the national and language rights of all minorities in Ukraine and in Russia, while emphasizing that a genuine right to self-determination (from autonomy within a unitary state up to and including independence) under no compulsion or threat of aggression and on an equal basis, ultimately cannot be guaranteed on the basis of capitalism and imperialism, but only through a struggle by independent working-class forces that bases itself on workers’ unity irrespective of nationality or language, arguing for international workers solidarity and for a socialist transformation of the region.

No rights of minorities will be secured by the war currently being fought, regardless of its outcome. Successful Russian annexations of occupied regions would lead to brutal repression of dissent and democratic rights, as well as bolster the criminal regime of Putin and the oligarchs. This has already been demonstrated with the so-called “republics” in Donetsk and Luhansk, with semi-military dictatorships, and the reactionary role of the Russian-controlled authorities in Crimea, where political repression intensified since the start of the war.

On the other hand, Ukrainian reconquest of the Crimean peninsula, for example, would not make the region fundamentally safe or democratic. Mykhailo Podolyak, top adviser to the Zelensky regime calls for the “Ukranization” of Crimea within a uniliteral state with no right to autonomy — even in contrast to its pre-2014 status (8 May). This runs against the mixed national moods and aspirations in the peninsula. In contrast, a workers’ government would support the right of the people of Crimea to decide their own fate based on the withdrawal of all military forces, and the calling of a revolutionary constituent assembly in which all national groups on the peninsula are represented.

Indeed Crimea’s only possible future on the basis of capitalism and imperialism is that of a permanently contested ultra-militarized near “no man’s land”, alternating between different forms of imperialist domination. If, at a certain stage, negotiations — which still appear to be a long way off— or continued stalemate produce a “frozen conflict”, it will only postpone new, bloodier conflicts, while low-intensity fighting continues out of the gaze of the world’s media. Those areas left under Russian occupation will suffer brutal repression and authoritarian rule, bolstering the bonapartist regime of Putin and the oligarchs, while Ukraine itself will be a highly militarized nationalistic society squeezed between Russian and Western imperialism, possibly with some imperialist powers offering meaningless, but costly security guarantees.

We call for an end to the war, brought about by mass working class action internationally. Such a movement should stand for the end of all imperialist interference in Ukraine. This means the withdrawal of Russian troops and no to NATO subjugation, including opposition to all Western ‘military aid’. It means opposing the reactionary regimes in Moscow and Kyiv as part of the struggle for international socialist change. Such a movement, particularly if it assumed a mass character in Ukraine, would clearly have great possibilities to undermine the effectiveness of the Russian invasion force, and open up the potential for a revolutionary crisis at the front and at the rear.

Only in conditions free from military occupation by any power/s can Ukraine exercise its right to exist, and all its inhabitants their right to self-determination. No “referenda” supervised by any gang of imperialists will provide any basis to resolve national and territorial questions in the region. We call for the building of mass working-class organizations to struggle against the war and all capitalist governments, and for working-class governments in Ukraine and Russia based on mass organizations of the multi-ethnic, multi-gendered working class, to create the conditions for all peoples of the region to determine their destiny freely on the basis of socialist planning and cooperation, not an ever-escalating carnival of nationalist reaction. We stand for a free and voluntary socialist federation of the region, as part of a socialist Europe and socialist world.

At the moment there is very little in the way of a genuine antiwar movement. There is also much confusion with some on the left advocating alliances with parts of the right and the far right who are “antiwar”. This is a dangerous path. It is urgent that there be an authentic voice of working class opposition to this war and to expose the complete falseness of the antiwar credentials of these right wing elements. ISA should therefore give more prominence to its antiwar, internationalist, anti-imperialist, programme on the war, and consider joint initiatives which test it out in action. This could include organizing an international day of action by ISA against the war in Ukraine, in conjunction with others on the left and the labor movement where appropriate, on the basis of a set of anti-imperialist and internationalist demands, alongside which we would clearly point towards a revolutionary socialist solution.

Yet even in absence of an anti-war movement, these processes are stimulating radicalization and struggle. The escalation of the New Cold War will continue to influence and aggravate the various crises afflicting global capitalism in the 2020s, provoking movements, struggles and events that in turn react upon the rhythm and tempo of the inter-imperialist conflict.

Supply-chain ruptures and disruptions caused by the immediate impact of the war in Ukraine, as well as the longer-term process of deglobalization, are key drivers of inflation — already spurring new class battles and fuelling social explosions in the neocolonial world, as seen recently in Syria and Pakistan. Increased inter-imperialist rivalry will undermine ‘co-operation’ in the face of the next recession and compound its devastating consequences. And, the fact that the first 7 months of the war alone released some 100 million tonnes of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere is but one example of capitalism’s false ‘concerns’ for the climate taking a backseat to the pursuit of profits, power and prestige.

Reaction will continue to rise amid the fumes of militarism. Bellicose nationalism goes hand in hand with a reinforcement of reactionary gender roles and hyper-masculinity, alongside a ramping up of sexism, racism, queerphobia and xenophobia. Likewise, the increase in state repression will have a disproportionate impact on the most oppressed layers in society and a burgeoning workers’ movement in many countries. Despite all the rhetoric of the US-led bloc claiming to defend democracy against autocracy, the growth of the far-right, the crackdown on democratic rights, the aggressive pursuit of deals with authoritarian and dictatorial regimes and the intensification of oppression are all nurtured by the escalation of the inter-imperialist rivalry and the historic crisis of capitalism. But the spewing up of ‘the muck of ages’ comes on the back of a mass (if uneven) radicalization amongst large sections of workers, youth and women who will not be dragged backwards, paving the way for explosive confrontations in the months and years ahead.