Valuable lessons for socialists

Elin Gauffin, Socialistisk Alternative (ISA in Sweden)

Ten years have passed since the incredibly dramatic summer of 2015, when the Greek working class stood face to face with the institutions of European capitalism. I recently read the book Syriza’s Rise and Fall in the same summer kitchen where, like many others, I followed the radio broadcasts from Greece minute by minute, and the flashbacks lit up my reading. We learned that OXI means “no” in Greek. Troika — a team of three horses — here meant the European Commission, the ECB and the IMF. On 5 July 2015, 61.3%of Greeks voted OXI to the troika’s austerity package in a referendum called by the Syriza government, and the world held its breath — what would happen next?

Jonas Karlsson has done a thorough, impressively persistent and commendable job. He began writing the book back in 2015 as part of his political conviction that workers’ struggle and social movements need to be organised around a party and a programme, and that left-wing parties need to be linked to movements. Syriza faced the most challenging test, and the book’s subtitle is very apt: Lessons for Europe’s Socialists. The book is not entirely easy to digest for many readers, with its many twists and turns and detailed descriptions of political factions. The aim is precisely to provide lessons for active socialists.

Karlsson sticks to the topic of Syriza, so the explanation of how Greece ended up in one of the worst debt crises ever is more of a brief summary. Capitalism is a system with inherent contradictions. This means that it repeatedly crashes into economic crises. The speculative economy that made the world feverish at the beginning of the millennium boosted the lending carousel, and many loans were unsecured. When interest rates rose, payments were suspended and banks collapsed. In the US and the EU, record amounts were spent on bailout packages to save the banks. The same willingness to act was lacking, or rather conditional, when the crisis hit individual states.

Greece had been a member of the EU for a long time and joined the currency union two years after its inception, introducing the euro as its currency in 2001. A relatively small and weak country was incorporated into the same currency union as Europe’s giants, without the possibility of influencing interest rates and exchange rates through devaluations. Greece’s budget deficit in 2009 was 12.7%, twice as high as the EU average. A smear campaign was launched by the powers that be in Brussels, to blame the crisis on something other than the system. The Greeks were accused of cheating and being lazy. But while tax evasion was widespread among Greek entrepreneurs, Greek wage earners worked the most hours per year of anyone on the continent and had some of the lowest wages.

The system was rigged. Greece ran a current account deficit with the stronger Germany and was forced to take out even more loans, not least from German banks, to finance this, at interest rates that were much higher than what others were paying. This, of course, exacerbated the budget deficit and further deteriorated Greece’s credit rating. Karlsson writes that at the end of 2010, Greece could only borrow at an interest rate of 12.5%, and in 2012, the interest rate on Greek government bonds on the secondary market was 40%.

It is important to emphasise that the EU is a union of capital. This was the intention from the outset when the Coal and Steel Union was established after the Second World War. At every stage of the EU’s development, the dominant aim has been to facilitate the mobility and position of European capital in relation to competitors in the East and West and in relation to the European working class. The whole story of the debt crisis of 2008-2010 really highlights this. The two bailout packages that Greece ultimately received between 2009 and 2015 were conditional on so-called memoranda that required huge cuts in welfare and wages. Private debts were converted into public debts. The real purpose was to rescue German and French banks, which accounted for half of Greece’s debts. The Truth Commission on Public Debt, appointed by the Greek Parliament, concluded that the real reason for the bailout packages was to rescue private banks from huge losses.

The first “rescue package” was adopted by the social democratic Pasok government in 2010 and provided the country with 110 billion euro in “aid”. Jonas Karlsson writes: “The Troika’s disastrous recipe can be summarised as inaccurate forecasts, with GDP falling more than expected in the pursuit of unreasonable budget surpluses, where large cuts destroyed both demand and the production base in the economy. Both physical capital and knowledge were lost. In 2015, GDP was 20% lower than the programme’s forecasts and public debt was 180% of GDP, compared to the first programme’s forecast of 148%. Between 2008 and 2015, GDP had fallen by 25%, 19% of which was since the Troika’s bailout programme began in 2010.”

Syriza is one of the parties formed to the left of the crisis-ridden social democratic and so-called communist parties in Europe in the 21st century. The historic event of a radical left-wing party coming to power for the first time in Greece coincided with the deep economic crisis. Before we get there, Jonas Karlsson thoroughly reviews the interesting history of the partisans during World War II, the strong Communist Party (KKE) that was banned after the war, the military dictatorship of 1967-1974, how radical Pasok was in the 1980s, the KKE’s divisions and sectarianism, and much more. Syriza emerged from Synaspismos, which consisted of splinter groups from the KKE and other parts of the Greek left. In 2004, the name Syriza was used for the first time as an alliance between Synaspismos and others.

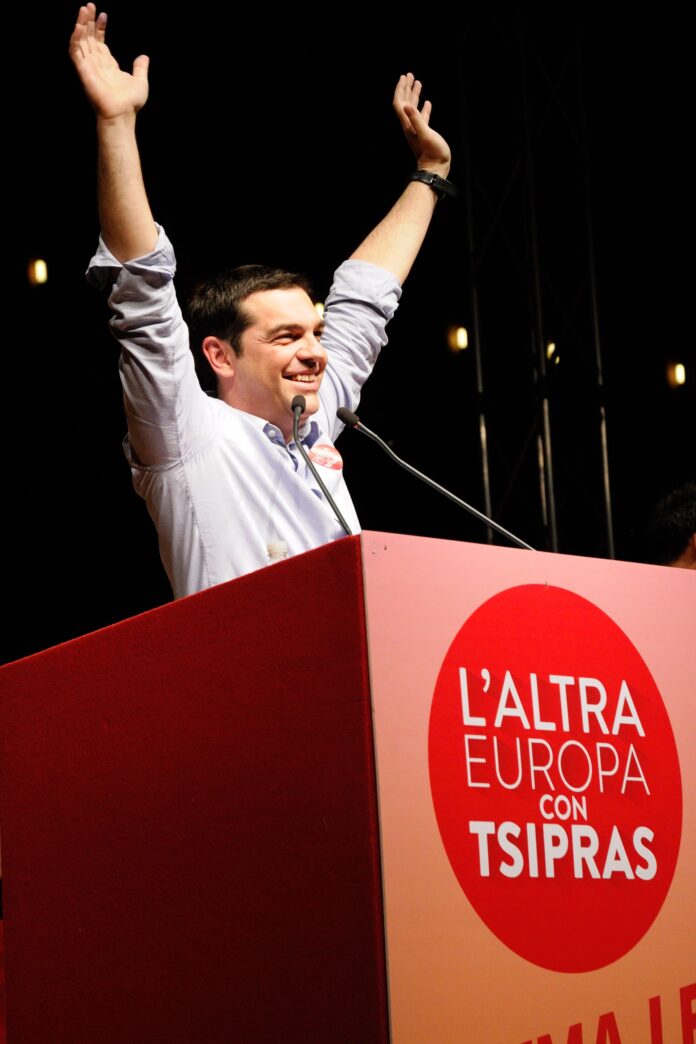

Alex Tsipras was very young when he first became president of Synaspismos in 2008 and took over the leadership of Syriza the following year. It was not until 2013 that Syriza held its founding congress and the organisations within Syriza were forced to disband. Syriza was more left-wing than Synaspismos and, under Tsipras’ leadership, Syriza oriented itself towards social movements. A notable example was when the party defended young people protesting against brutal and sometimes lethal police violence.

Struggle was widespread in the early 2010s. It spread across all crisis-hit countries, especially in southern Europe. These were not small, peripheral tent occupations. On the international day of protest on 29 May 2011, 100,000 people demonstrated in Syntagma Square in Athens, and 300,000 on the second day of protest on 5 June. Police violence was brutal; 250 demonstrators were injured on 28 June. Student occupations of virtually all schools and universities were part of the movement. Strikes paralysed the country. “By the end of the year [2011], there had been a total of 445 strikes, including six 24-hour general strikes and two 48-hour general strikes. The pressure created by the movement also affected Syriza, which changed its initial position that the debt should be paid by “taxing the rich” to demanding debt relief,” writes Jonas Karlsson in a key sentence in the book.

The impact of the crisis and the “rescue packages” was brutal. In the summer of 2013, unemployment reached 28.3%, 30% lacked health insurance and 600,000 children were living in poverty. The right-wing New Democracy party normalised racism and the far right began to grow, with the violent neo-Nazi party Golden Dawn, whose members murdered left-wing activist and rapper Pavlos Fyssas in 2013. Anti-fascist mobilisation in the streets pushed back the fascists, and Jonas Karlsson correctly notes that banning Golden Dawn did not help. Today, there are three far-right parties in parliament: Greek Solution, Niki and the Spartans.

Syriza’s opposition to the austerity measures earned them 36.3% of the vote in the January 2015 election. However, they were unable to form a government on their own. Tsipras chose the small conservative party Independent Greeks, Anel, as a coalition partner and gave them key positions. Karlsson writes, “Syriza’s decision to hand over responsibility and control of both the military and the police was hardly a coincidence, but must be seen as a signal that the government would not challenge the system but would preserve “stability” and “law and order”. The EU wanted to crush the first radical left-wing government to set an example, and they succeeded.

On 13 July, a week after the referendum with such a clear “no” message, after a 10-hour meeting between Tsipras and the EU’s Angela Merkel, Tsipras signed a new agreement containing new draconian cuts and privatisations. “Syriza’s promise to stop the austerity measures was pulverised. Tsipras had capitulated.”

Capitalism had put pressure on the left-wing government via a special means — capital flight. €270 billion was taken out of the country between December 2014 and May 2015. Karlsson emphasises the importance of capital controls as a tool for the left. On the other hand, the EU was terrified that Greece would leave the union, triggering a wave of other countries leaving and a total crisis for the EU. “Refuse to pay” was the slogan of the workers and the most famous member of the new government was the finance minister, the charismatic left-wing professor Yanis Varoufakis, who had developed his own algorithm for tackling tax evasion. He did not get a chance to implement it, but had to negotiate immediately with the European powers and has described how decisions in the “negotiations” had always already been made elsewhere in advance. As early as 30 January, the President of the Eurogroup came to Greece and demanded that the memorandum be finalised — otherwise the banks would be closed. On 4 February, the European Central Bank decided to cut off liquidity for young Greeks across Europe. Even the Truth Commission on Public Debt concluded that the memorandum was illegal. In the end, the German state earned €2.9 billion in interest in the Greek crisis and the European Central Bank earned €7.8 billion between 2012 and 2016.

In total, the Syriza government implemented six austerity packages on top of the nine implemented by previous governments. Some relief was provided for the poorest, but overall it was a disaster. Among other things, there was an increase in VAT on food; pensions were cut by 25% and the retirement age was raised significantly; the right to strike and employment protection were weakened (the proportion of employees with collective agreements fell from 85% to 10% during the crisis years); and there were massive privatisations of entire islands and ports.

All previous criticism of Israel was dropped and cooperation was established. The Pasok government before Syriza was responsible for lowering the minimum wage by 22% to 700 euro per month and laying off 150,000 public sector employees.

The end of the book contains 65 lessons for socialists. They are important and deserve to be read separately. There are headings such as “Cuts are devastating for the left”, “People don’t care about the scandals of the right” and “Walk in step with the people and have support for your politics”. I think the point “Greece should have left the currency union” is the most important and that it deserved more space. Jonas Karlsson believes that Syriza should have taken Greece out of the euro (Grexit) and written off the debt, but above all, prepared for a new digital currency earlier, after winning the election. However, this would have required more than these steps alone.

As Karlsson notes, the struggle and strikes had subsided in 2015. But Syriza and Greece were actually in a potentially revolutionary situation where a break with the troika and a Grexit meant a break with the economic system of capitalism. To be implemented, the party’s program would have needed the working-class to be mobilised. Through local mass meetings across the country, Syriza should have built up a mass dialogue on the steps that needed to be taken. The strike movement did not exist in the spring of 2015, but the main criticism of Tsipras should be that Syriza did not turn outward to build that movement. Jonas Karlsson is right that the working class must take power over society — but this applies to more than just “exchange services, local cooperative banks and social centres”; it also applies, above all, to large companies, banks and the state.

On 16 June 2015, Offensiv (paper of ISA in Sweden) wrote: “These and other loans cannot be repaid. The Syriza government must refuse to pay the loans, introduce currency and capital controls, nationalise banks and large companies, and appeal for support from workers in the rest of Europe. If the Syriza government is to be able to fulfil its election promises, Greece must throw off the straitjacket of the EU and the euro, and the masses must be mobilised to fight to abolish capitalism. So far, however, the Syriza government has done nothing to prepare the masses for such a struggle. This, in turn, opens the door to a last-minute deal with the Troika. ”In Syriza’s Rise and Fall, it is noted that the state is not neutral, but stands on the side of capital at the end of the day. Ultimately, defending welfare and a decent life for all will mean an inevitable confrontation with capitalism and its states. Therefore, workers need to organise not only in new broad left parties, but also around revolutionary perspectives and revolutionary leaderships that build the party in the mass struggle, far beyond the limits of parliamentarism.